Monergism and the Heresy of Monotheletism

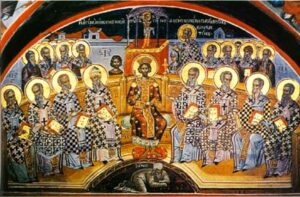

Much of the Reformed tradition’s Christology and Trinitarian theology came out of the ancient Ecumenical Councils. There were many gatherings in the early Church. Many were local councils but the great Councils made decisions that would ensure the wellbeing of the entire Church (hence the name “Ecumenical”). These gatherings followed the precedent by the Jerusalem Council in Acts 15 and are the fulfillment of Christ’s promise that the Holy Spirit would guide the Church into all truth (John 16:13). The early Church was challenged by heresies and it repudiated these heresies and defined right doctrine through gatherings of church leaders that represented the whole church, these came to be known as Ecumenical Councils. For example, the first Ecumenical Council (Nicea I in AD 325) repudiated the heresy that Christ was a created being and affirmed the divinity of Jesus Christ, the second Ecumenical Council (Constantinople I in AD 381) affirmed the divinity of the Holy Spirit, the third Ecumenical Council (Ephesus in AD 431) affirmed the two natures of Christ (see Kallistos Ware’s The Orthodox Church pp. 20 to 35).

The sixth Ecumenical Council repudiated monotheletism, the heresy that Jesus Christ had only a divine will, and affirmed that Christ possessed both a divine and a human will. While many Protestants may not have heard of the heresy of monotheletism, the issue is crucial to having a healthy orthodox Christology. It is not an obscure minor theological issue but one of tremendous implications for proper Christology and one that required action by an ecumenical (universal) council. Protestantism’s historical amnesia has often made it vulnerable to erroneous doctrines. I urge my Reformed friends to take seriously what I have to say about Reformed monergism and the heresy of monotheletism.

The Reformed insistence on the priority of the divine will over human will (monergism) parallels the heresy of monotheletism — the teaching that Christ did not have two wills, only a divine will. In repudiating monotheletism the Sixth Ecumenical Council affirmed that Christ’s humanity possessed a free will that worked in harmony with the will of the divine Logos. This was not an arbitrary ruling but an outworking of the Chalcedonian Formula’s teaching that Jesus Christ is fully God and fully man. Thus, to be human means having a body, a mind, a soul, and a will. To deny any of these leads to a defective and heretical Christology. This understanding of Christ’s human nature having a fully human will like Adam’s and our’s leads to the affirmation that humans have a free will as well, albeit one injured by the Fall and in need of healing. By assuming the totality of human nature, Christ was able to bring about our salvation. Gregory of Nazianzen wrote:

For that which He [Christ] has not assumed He has not healed; but that which is united to His Godhead is also saved. If only half Adam fell, then that which Christ assumes and saves may be half also; but if the whole of his nature fell, it must be united to the whole nature of Him that was begotten, and so be saved as a whole (Ep. CI, To Cledonius the Priest Against Apollinarius; NPNF Series 2 Vol. VII p. 440).

This is quite different from the Reformed understanding that the Fall result in our wills being totally depraved, “neither able nor willing to return to God” according to the Canons of Dort.

The Cappadocians assigning priority to the hypostases shaped not just Orthodoxy’s understanding of the Trinity but also Maximus the Confessor’s understanding of the Incarnation as instrumental for our salvation. [Note: Readers who want to better understand the issues involved in the monothetism controversy are advised to get Maximus the Confessor (1996) edited by Andrew Louth.]

Maximus wrote:

Because of this, the Creator of nature himself — who has ever heard of anything so truly awesome! — has clothed himself with our nature, without change uniting it hypostatically to himself, in order to check what has been borne away, and gather it to himself, so that, gathered to himself, our nature may no longer have any difference from in its inclination. (Maximus the Confessor Letter 2 in Louth p. 91)

Orthodoxy’s emphasis on the hypostasis influences its understanding of the Incarnation, the sacraments, and theosis.

Monergism vs. Free Will

The Western emphasis on Being leads to determinacy and to Calvin’s insistence on God’s absolute sovereignty. In his attempt to construct a logically coherent theology Calvin has created other problems. The doctrine of Irresistible Grace contains an internal contradiction: God’s free gift of grace is based on compulsion. Bishop Kallistos Ware wrote:

Where there is no freedom, there can be no love. Compulsion excludes love; as Paul Evdokimov used to say, God can do everything except compel us to love him (Ware 1986:76; emphasis in original).

If there is no free will, then there is no genuine love, nor can there be genuine faith. In Calvinistic anthropology, humans do love God and one another freely but with the haunting a priori that their love is a mere consequence of God’s ordained decree, not because of their free choice.

The Reformed tradition does affirm free will but qualifies it to the extent that one wonders whether free will is essential to human existence. Basically, the Reformed position on human free will can be summed up in the following:

(1) Humanity possessed free will prior to the Fall (Dort Article 1 “The Effect of the Fall on Human Nature”; Westminster Confession IX.2);

(2) Humanity lost all capacity for free will after the Fall (Dort Article 3 “Total Inability,” Westminster IX.3);

(3) Faith in Christ is the result of divine election and divine grace working on us, (Dort Article 12 ‘Regeneration a Supernatural Work, Westminster X.1-2);

(4) The perseverance (preservation) of the saints is due solely to divine grace (Dort Article 8 “The Certainty of this Preservation,” Westminster Chapter XVII.2); and

(5) Free will is restored to humanity when they are in the “state of glory” (Westminster Chapter IX).

The last statement doesn’t make sense. Logically, it would mean the possibility of apostasy in the age to come. Thus, according to the Reformed theological system the only time humanity ever possessed the freedom with respect to their relationship with God was prior to the Fall but not after.

The Orthodox approach to free will is that humans possessed an undistorted free will prior to the Fall but after the Fall human free will became damaged or wounded. Christian conversion is understood as our free response to God’s grace by trusting in Christ and our participation in the life of the Church, the Body of Christ. Orthodoxy’s affirmation of free will after the Fall allows for the possibility of people falling away, but it also allows for the possibility of restoration. The Orthodox sacrament of confession is based on our turning back to God (repentance) and the mercies of God. God in his mercy will welcome us back but this is contingent on our choosing to come back home like the lost Prodigal Son (Luke 15). The father in Jesus’ great parable waited, he did not compel. For this reason Orthodoxy insists that the eternal destiny of individuals is a mystery.

The ascetic disciplines prescribed by the Orthodox Church are based on prayer and the denying of the passions; through these spiritual exercises our wills along with our minds are sanctified and redeemed. The Orthodox approach to sanctification is therapeutic and progressive. As we grow in prayer and in our love for God and our neighbor our wills damaged by the Fall are restored to the health and integrity God intended for us. During Lent the Orthodox Church warns her members against legalism. This is in recognition that a legalistic approach to the Christian life being based on fear and compulsion is the opposite of a spiritual life based on contrition for sins and a yearning for God.

The Possibility of Free Will

Orthodoxy affirms free will because humanity being created in the divine image is foundational to its theology. Eastern Orthodoxy’s anthropology being rooted in a trinitarian understanding of God leads us to a soteriology grounded in freedom as relationship, i.e., the freedom of love. Kallistos Ware wrote:

Without freedom there would be no sin. But without freedom man would not be in God’s image; without freedom man would not be capable of entering into communion with God in a relationship of love (Ware 1986:76).

Being created in the image of the Triune God means not only rationality but also morality, that is, the freedom and ability to choose. The two together form the basis for our being able to love God and one another. Nor is there any notion here in Orthodox anthropology of free will stealing any of God’s glory, frustrating God’s purposes, or granting merit to man because of his choice. These are all problems invented by Western theological categories.

There is a profound difference in the way the West and Orthodoxy understand freedom. In the West freedom is understood to arise from perfect self-possession, self-autonomy, and self-direction, but for the Orthodox freedom arises from ecstasis and self-transcendence, going beyond ourselves (Lacugna 1991:261). The freedom spoken of here is based on the communion of persons, not the fulfillment of autonomous individuals. Zizioulas draws the distinction between the individual and the person noting that the individual becomes a person by loving and being loved (Zizioulas 1985:48-49). True human freedom means going beyond our individual self and becoming open to others which finds its ultimate fulfillment in union with Christ and life in the Trinity.

Eastern Orthodoxy’s emphasis on the person (hypostasis) leads to freedom and relationality.

The fact that God exists because of the Father shows that His existence, His being is the consequence of a free person; which means, in the in the last analysis, that not only communion but also freedom, the free person, constitutes true being. True being comes only from the free person, from the person who loves freely–that is, who freely affirms his being, his identity, by means of an event of communion with other persons (Zizioulas 1985:18; emphasis in original).

This in turn opens the way for perichoresis, the idea that the three Persons of the Trinity mutually inhere in one another (LaCugna 1991:270 ff.). Perichoresis lays the foundation for the idea of persons in communion, both in terms of intradivine relations within the Trinity and our being invited (elected) into that interpersonal communion. (See John of Damascus’ De Fide Orthodoxa Chapter VIII (NPNF Vol. 2 page 11 Note 8).)

Salvation in Christ has an eschatological element. Justification, regeneration, and sanctification represent the beginning of our salvation in Christ. The ultimate goal of our salvation is theosis, becoming sharers in the divine nature and the kingdom of God (see II Peter 1:4). Kallistos Ware wrote:

The final end of the spiritual Way is that we humans should also become part of this Trinitarian coinherence or perichoresis, being wholly taken up into the circle of love that exists within God (1986:34; emphasis in original).

At the heart of Orthodoxy is the vision of life in Christ as communion with the Holy Trinity, the three divine Persons forever united in love. This interpersonal understanding of salvation can be found in John 17:21: “May they all be one: as thou, Father, art in me, and I in thee, so may they also be one in us.”

The Question of Universalism

One of the greatest challenge to Calvinism is the question: How can a loving God send people to hell? Calvin’s answer is God’s just and inscrutable sovereignty.

We assert that, with respect to the elect, this plan was founded upon his freely given mercy, without regard to human worth; but by his just and irreprehensible but incomprehensible judgment he has barred the door of life to those whom he has given over to damnation (Institutes 3.21.7, Calvin 1960:931; italics added; see also Institutes 3.21.1, Calvin 1960:922-923).

Many people’s reaction to predestination has been one of revulsion. Philip Schaff in his concluding remarks to his survey of Calvin notes:

Our best feelings, which God himself has planted in our hearts, instinctively revolt against the thought that a God of infinite love and justice should create millions of immortal beings in his own image–probably more than half of the human race–in order to hurry them from the womb to the tomb, and from the tomb to everlasting doom! And this not for any actual sin of their own, but simply for the transgression of Adam of which they never heard, and which God himself not only permitted, but somehow foreordained. This, if true, would indeed be a “decretum horribile” (Schaff 1910:559).

The underlying ethos of Calvinism is not the warm heart religion of popular Evangelicalism or the fervent emotionalism of Pentecostalism, but the more stern and demanding religion that calls for submission and domination. Karl Barth characterized the spirit of Calvinism:

Calvin is not what we usually imagine an apostle of love and peace to be. …. What we find is a hard and prickly skin. The blossom has gone, the fruit has not yet come. An iron age has come that calls for iron believers” (1922:117).

In reaction to the Calvinist double predestination liberal Protestantism propounded the doctrine of universalism: All are destined to go to heaven. However attractive such a doctrine may be, it suffers from a flaw similar to that found in Calvinism. Underlying Liberalism’s sunny optimism is a blithe disregard towards human agency. A friend of mine who served on the pastoral staff of a large liberal mainline Protestant church once asked me what I thought about her colleague’s teaching that everyone will be in heaven. I answered: “You mean everyone is going to end up in heaven, whether they want to be there or not?”

Ironically, Liberalism’s universalism is a mirror image of Calvinism’s double predestination. Where Calvinism believes in a God who arbitrarily selects some to be saved regardless of their choice), Protestant Liberalism believes in a God who indiscriminately selects all to be saved (irregardless of their choice). Liberalism ultimately denies to all humanity the free choice of hell. Calvinism despite its talk of grace and mercy is determined to deny to all humanity the free choice of heaven.

The Orthodox response to this question is: “God doesn’t send anyone to hell. People choose hell when they choose life apart from God.” To put it another way, God “sends” only those who have freely chosen hell for themselves. Bishop Kallistos Ware wrote:

St Isaac the Syrian says, ‘It is wrong to imagine that sinners in hell are cut off from the love of God.’ Divine love is everywhere, and rejects no one. But we on our side are free to reject divine love: we cannot, however, do so without inflicting pain upon ourselves, and the more final our rejection the more bitter our suffering (in Ware 1986:182).

Thus, the Orthodox understanding of hell is more just, compassionate, and tragic in comparison to the Reformed view. While Orthodoxy disallows universalism as a dogma, the question as to how many shall be ultimately saved is left open. For a discussion of the complex nature of this question see Kallistos Ware’s “Dare We Hope for the Salvation of All?” in The Inner Kingdom (2000:193-215).

Summary

TULIP forms a coherent theological system that explains the Reformed doctrine of predestination. When we consider TULIP as a whole, its underlying premises, and its consequences we find it incompatible with Orthodoxy and hopefully unacceptable to others as well. The doctrines of Total Depravity and Irresistible Grace by denying the basis for human free will undermine the basis for faith and love. This denial of free will constitutes a denial of the core of human existence, the imago dei. This denial of human free will implies the heresy of monotheletism — the denial that Christ’s human nature had a free will. The doctrine of Limited Atonement is alien to Orthodoxy for two reasons: (1) it is based upon the notion of quantifiable legal merit, and (2) it sets limits on God’s infinite love. Where the initials T and I relate to the Reformed understanding of human nature, the initials U and P relate to their understanding of God. The doctrines of Unconditional Election and the Preservation of the Saints uphold God’s absolute sovereignty in our salvation. This understanding of God as an arbitrary omnipotent Monarch can be traced to the Western Augustinian tradition which emphasizes the divine Essence as the basis for unity of the Trinity. This forms the basis for the forensic approach to salvation which emphasizes legal righteousness and the transference of legal merit. Orthodoxy following the Cappadocian Fathers locates the unity of the Godhead in the Person of the Father. This emphasis on the Person lays the basis for the understanding of God as eternal communion of Persons: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. It also leads to Chalcedonian Christology which teaches that Christ’s two natures are united in one Person for our salvation. This emphasis on the Person informs the Orthodox approach to salvation: the need for personal faith in Christ, salvation as union with Christ and in the Church; theosis as personal union with Christ that transforms us, and eternal life as communion with the Triune God.

The Goal of Our Salvation: Life in the Trinity

When we read the famous opening lines of the Westminster Shorter Catechism — Q. What is the chief end of man? A. Man’s chief end is to glorify God and enjoy him forever — we find missing any reference to the Trinity and any understanding of eternal life as communion with God. This is not surprising in light of the analysis we just did showing how the Western Augustinian approach to the Trinity tends to emphasize the Essence of the Godhead over the communion of Persons. Orthodoxy has a quite different vision of eternal life. It anticipates eternal life as living in communion with the Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. St. Isaac the Syrian wrote:

Love is the kingdom which the Lord mystically promised to the disciples, when he said that they would eat in his kingdom: ‘You shall eat and drink at my table in my kingdom’ (Luke 22:30). What should they eat and drink, if not love?

When we have reached love, we have reached God and our journey is complete. We have crossed over to the island which lies beyond the world, where are the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit: to whom be glory and dominion. May God make us worthy to fear and love him. Amen. (in Ware 1986:51)

Robert Arakaki

Robert,

This is good stuff. i was raised in a non-Calvinist denomination, but i read a lot of reformed guy during my own protestant theological development (especially literature about presuppositional apologetics).

Anyway, have you heard of the brand of universalism that still affirms that people will be in hell? The idea was introduced to me by Richard Beck who runs the “Experimental Theology” blog. He said he doesn’t deny a final judgment and many people going to hell, he just believes God will continue to try to woo those people in hell for eternity, and God is ‘all-competent,’ so He’ll eventually win them all over. What do you make of this?

Best,

–guy

***For that which He [Christ] has not assumed He has not healed; but that which is united to His Godhead is also saved.***

Something I’ve wondered: did Logos assume a human body or the genus of “human nature”?

Jacob,

When you say

quote:

“Something I’ve wondered: did Logos assume a human body”

Do you mean this in the context of Adoptionism,?

Do you mean this in the context of Diodorus of Tarsus, Theodore of Mopsuestia, and Nestorius?

Or do you mean this in some other context? In some other sense?

Robert,

Greetings! It has been a long time since I’ve commented.

One notion that needs, in my mind, further qualification is that of ‘freedom.’ You do note that the East and West view it differently. I’m wondering if we can qualify it a bit further, so as to avoid confusion.

A personal example may help my to put my desire into words: I teach a Humanities class at the collegiate level that deals (or dealt: we’ve changed the curriculum a bit) with the question of freedom, specifically of the will (we used the Luther-Erasmus debate and some writings from Pope John Paul II). My contention, as teacher, is that the will can only be ‘free’ when it submits to the law of God (conceived broadly as the norms in which life can flourish, not necessarily in a Rushdoony-Reconstructionist sense): if we choose sin, for example, we choose bondage for the will rather than freedom. Another example is that if we choose to jump off a building (which may or may not be a moral fault), our will is bound to the consequences of that action (in this case, “splat”) and therefore not free. A student pushed back at this, claiming that it her will was not absolutely free, then all of life was determined (and this person was not a Calvinist, either). So the definition of ‘free’ came to a head: are there certain limitations and boundaries in which something can be truly ‘free’ (that is, can partake of and participate in Life), or must there be no boundaries for something to be ‘free?’ My guess is that you would say that there must be boundaries (I almost think that this point should be obvious, but having that student has made me wary of ‘obvious’ things): the question becomes, what are the boundaries that constitute the possibility of freedom? Concomitant to that is, what are the effects of sin on the will? Does sin, as a state of corruption that leads to death (I know that this doesn’t exhaust what sin is, but is only part of it), affect our participation in the necessary (the ‘natural’ laws such as gravity) and sufficient (Christ’s work) causes of Life? What does sin do to our will? Cripple it? Sicken it? Kill it? Totally enslave it? Blind it? Bind it? If will are born in sin, that is separated from God and liable to death, what does that do to our power of choice? Are we, so hampered by corruption, really able to turn ourselves to God? Is a slave of a master able to serve another Master while still in the former’s service?

I hope this makes sense. Volition is one of the trickier subjects for us humans to ponder, especially once it gets to the level of nature or person (is volition an energy of the person, or a part of the nature; what is the relationship between energy and nature; etc.).

Russ

BH, I looked up “genus” in the dictionary. It has to do with biological taxonomy. It would seem to me, therefore, by definition, to be human (to have the genus, homo sapiens?) is to have a human nature and a human body both. How can these be separated? Thus, your question appears non-sensical to me. I believe it is nonsensical from an Orthodox theological/philosophical perspective as well. To have a human body is to have a human nature also. God, the Word, could not assume a human body (take on our flesh) without also assuming human nature (in its entirety), so He has a human will, spirit, soul, etc., as well as a human body–a human being, by definition, being a creature in the image of God–a body-spirit/soul unity. In Orthodoxy, Christ is understood to have both a Divine nature and a human nature (which He took from Mary in her womb, and which obviously includes the body, but is not limited to it as if a human body could be separated from the whole human nature). These two natures are in Jesus Christ united in one Person (person = “hypostasis”). The idea that the Incarnation means the Divine nature of the Logos (the Divine Spirit?) filled a human body (like an empty shell) is Gnostic, not orthodox Christian, but perhaps you understand that, and I have not properly understood your question.

I was using it in the sense it was used in Hellenistic terminology, both pagan and Christian.

Did Christ take the abstract form of “humanity” or a human body?

Does this have to be an either/or? Christ took on “human nature” (that is, the logoi the make us human) and a specific human body. They exist together, not separately. We can make abstract observations about human nature, but we are talking about God’s word that gives us form. Roy Clouser does a nice job with this in his “The Myth of Religious Neutrality” — it is rather close to St. Maximos the Confessor’s “logoi/Logos” thinking.

Russ

Did the first Adam bring corruption and death to his own body only, or to all human nature?

ontologically or federally? I hold the latter view.

Your WCF 6:2 says man became dead in sin and wholly defiled in all the faculties and parts of soul and body. (Ontological)

WCF 6:3 says the guilt of this is imputed (Federal) but death and corruption is conveyed by ordinary generation. (Ontological)

And for good measure, 6:3 adds that your nature and all it’s motions are truly and properly sin.

i know that. we r defining terms differently. more later

Thanks Robert for making a post about this issue. When I saw that the majority of the Reformed were advocates of creationism while some others were advocates of traducianism. The first thought that came to my mind was the Saint Gregory quote you posted.

Gregory of Nazianzen wrote:

For that which He [Christ] has not assumed He has not healed; but that which is united to His Godhead is also saved. If only half Adam fell, then that which Christ assumes and saves may be half also; but if the whole of his nature fell, it must be united to the whole nature of Him that was begotten, and so be saved as a whole (Ep. CI, To Cledonius the Priest Against Apollinarius; NPNF Series 2 Vol. VII p. 440).

But some church fathers were creationists while others were traducianists and so it’s complicated. But what made it even more complicated to me was that it seemed as if even a traducianist could be a creationist in regards to Christ, but not in regards to the rest of humanity. Especially if one factors in the federal headship view which seems to want to make the application of the western interpretation of original sin depended on the male. But are all Reformed protestants advocates of the federal headship view? If federal theology is linked to Johannes Cocceius(1603-69) then what was the view of John Calvin and the other first generation reformers?

Also, there is something about the federal view that seems disconnected to me. I don’t know. It seems more legal than organic. As if the fall itself was some type of forensic wickedness or something. I say this because it’s application is depended on all male descentents after him. They seem to ignore the fact that flesh from a woman’s flesh still means that you are of Adam. Some don’t want to say that Jesus is of Adam. If Jesus is not of Adam then can they really believe this highlighted part from the Council of Chalcedon?

“homoousios with the Father in regards to Divinity, and at the same time homoousios with us in regards to humanity;”

I don’t know. But I loved your article!

Jnorm,

This is what was being foisted at us on Jacob’s blog. Christ did not come from male seed so he did not inherit sin in his nature. I don’t buy it. Mary’s nature is Adam’s nature is our nature is Christ’s nature.

The Westminster Divines argue Adam’s sin AND GUILT pass to all humanity via “ordinary generation”. Since Christ inherited all his humanity via Mary’s humanity, it seems the consistent Calvinist would of necessity have to argue the human nature Mary passed on to Christ is “totally depraved” only able to sin and do no good thing before “regeneration”. Yet for Christ to be “in all points tempted as we…yet without sin” He must be regenerated by the Holy Spirit in the womb instantanious to His conception, to avoid sinning — His regenerate but still fallen human nature now yielding in perfect obedience to His divine nature. (It seems that John the Baptizer was also regenerate in the womb — though perhaps not instantaneous to his conception.)

If I understand Orthodox anthropology after Adam, the human nature Christ’s inherits from Mary need not be instantaniously regenerate to conception because it is never enslaved to a Total Depravity…or bearing Adam’s guilt. Though Fallen and inclined to sin…it need not of necessity sin at every opportunity, void of all ability to do good. Thus Christ is from conception in the womb, strengthened by His Divine Nature never to sin or yield to his human nature inclination. Needless to say, a Calvinstic anthropology of inherited Total Depravity does throw a bit of a monkey wrench into the Incarnation/Christology of a sinless Savior.

Do you have a specific post in mind? Is it something I said or something Drake said?

Jnorm,

I’m glad you liked the article. And thanks for teaching me a new word: traducianism.

I’m not that well acquainted with federal theology even though I have been influenced by some Reformed theologians who wrote on the importance of the covenant. One particular person that comes to mind is Richard DeRidder who wrote Discipling the Nations. Another is Meredith Kline. I agree that the federal view can be more legal than organic but there have been some biblical research that brought the more personal and organic dimension to bear on the biblical concept of covenant. There are two kinds of covenants: (1) the suzerain covenant and (2) the parity covenant. The parity covenant is between two equals and usually involves an exchange of goods. You give me money and I give you my car. Once the transaction is completed we go our separate ways. But in the suzerain covenant a king comes to a city or nation and makes an offer: Be my subject and I will protect you. In the suzerain covenant you cease to be your own person and instead become part of the Lord’s person. In the ancient Near Eastern treaties the suzerain would have the terms of the treaty written down as a reminder for the subject. Furthermore, the suzerain and the subject would sit down for a meal as a sign of their covenant relationship. See how it points to the Eucharist? What I like about this biblical model is that it is much more personal and organic than the more common abstract juridical model that dominates Western theology. One doesn’t so much break the law as one disobeys the Suzerain to whom you are accountable to. This approach explains why the personal dimension quite often supersedes the written law in the Bible. I’m hoping one of these days to do a posting on how the biblical notion of covenant lays the groundwork for Orthodoxy.

Robert

I am also glad to see that Jnorm said that Church Fathers held to both creat. and traduc. It’s a tough debate and few are worthy of it. Yes, most Calvinists hold to the creat. view because *most people throughout history held to it,* of all persuasions.

Both positions have problems and if you read most systematics, they don’t spend too much time on it.

This sounds like a fruitful area for a systematics corrective to be applied.

Russ

Another suggestion for comparing/contrast Calvinism and Orthodoxy:

Do a post contrasting the Orthodox social ethic embodied in the Byzantine Symphonia with a Reformed position. That would be interesting since a lot of folks I know talk about how wonderful the symphonia is, yet few, even published scholars, have given a coherent account of it. McGuckin’s is probably the best.

I concur, especially since I was taught in my collegiate level that the East was Caesaropapist (which I have learned, as I now teach that very same class, isn’t the case — history is much more complicated). A look at the political teachings and traditions of both side by side would be exceedingly helpful and provocative.

Russ

If I understand Robert’s article here, it seems to express ideas that I’ve been pursuing as of late, myself. Namely, that according to the 6th council, Christ had two wills, both free, neither dominating or predetermining the other, working together in perfect harmony. The human will in total but free submission to the divine will. And for those who are in Christ, this is the goal toward which we aspire in salvation…deification, theosis, “total sanctification,” call it what you may…essentially consists in our will becoming absolutely purified, and in total but totally free submission to the will of God. Thus our “participation” in the Incarnation is completely realized.

Is that the gist?

In this case, you seem to have a strong case against the Calvinistic/Monergistic view. If Christ’s incarnation is the model for our salvation, then it must be (as you said) that Christ’s human will was in some way subjugated to, or predetermined by, the divine, which violates the council.

So I have two questions:

1. Has Reformed theology, in any formal way, ever formally accepted or formally repudiated the 6th Council? I never once heard any discussion about any council beyond Chalcedon in my 6 years in Reformed circles, except the condemnation of the 7th.

2. Is it possible that a Reformed person who accepts the arguments you’ve laid out above, could reconcile to the 6th Council by saying “BEFORE a person is (monergistically) regenerated, he has no freedom to submit his will to God’s, but AFTER he is regenerated (and justified by faith alone!) then his human will relates to God’s as does Christ’s?”

Bill,

#1. The Reformed do not submit to the authority of any Council. This would necessarily mean submission to the church of the Councils and this they disavow. I do not have Confessional statements in front of me in which they speak in this regard (Lutheran, Reformed, Anglican etc), as I am at work. They will submit to certain propositions within Councils, by picking and choosing, depending on the interpretation of the group they are with.

#2 The church of the 6th Council did not espouse monergistic regeneration. The scripture does not support monergistic regeneration. Both repeatedly affirm regeneration to be baptismal. If human nature and will needs a sovereign jumpstart (monergism), you then have mon-energism/monotheletism.

We make a distinction between ministerial and magisterial authority.

As to monergism, Drake explained this to you: the Reformed ordo does not terminate at regeneration.

Thanks, Canadian. I recognize that they do not submit to any council (at least they claim not to). However, they generally do say “we accept the teachings of the first four ecumenical councils as being consistent with Scripture.” I have never seen such a statement, pro or con, with respect to the teachings of the 6th council. I have with the 7th…plenty of iconoclastic arguments are leveled against it, “It breaks the plain meaning of the 2nd commandment,” etc. That’s the sense in which I’m asking the question. Has any body of Reformed believers/teachers ever said “We accept the positions of the 6th council” as they do the first four, or “We reject the positions of the 6th council” as they do the 7th.

Maybe a better question to ask is, has any formal position on mon-energism/monotheletism been articulated by Reformed confessions or councils? Or even prominent textbooks?

My other comment hasn’t been approved yet:

“””Maybe a better question to ask is, has any formal position on mon-energism/monotheletism been articulated by Reformed confessions or councils? Or even prominent textbooks?””””

Indirectly, yes. A guy named Drake has clearly articulated this. The Reformed position is monergistic regarding regeneration, synergistic regarding conversion. Either way, it is very misleading to simply tag the Reformed ordo as “monergistic.” In a certain sense, it could be, but that doesn’t tell the whole story. WGT Shedd makes this very clear, as does Rev. John Weaver.

Bayou Huguenot,

I wrote in Plucking the TULIP (1) regarding the Preservation of the Saints that the Reformed understanding of this aspect of the order of salvation is monergistic. I cited the Synod of Dort:

I also cited from John Calvin:

The preservation of the saints takes up pretty much the entirety of the order of salvation.

You can assert that the Reformed ordo is not simply moergistic but can be viewed synergistically. However, to be convincing you will need to cite authoritative sources like Calvin, the Westminster Confession, or the Synod of Dort. You will need to give specific citations showing how these sources viewed specific aspects of the order of salvation synergistically. Making broad statements based on obscure theologians like WGT Shedd and the Rev. John Weaver doesn’t cut it. In my postings I do my best to make sure that my assertions are backed up by citations from authoritative sources. I hope you will do the same.

Robert

You cannot support monergistic regeneration from scripture or history. It is, rather, a logical necessity for your system. And as WCF 6:3 says, your nature and all it’s motions are truly and properly sin. There is not true synergy or reciprocation there. And then changes must be made to how this is all applied to Christ our God in the Incarnation.

Isn’t the Reformed position monergistic again in regards to P.O.T.S. (perseverance of the saints)?

And so does it really matter if the Reformed ordo is suppose to be Monergistic in regards to Regeneration and Synergistic in regards to Sanctification?

At some point in time, monergism must bleed into the Reformed category of Sanctification, or else you would have to believe it’s possible to fall from grace.

Also, some Reformed believe in Monergism in both Regeneration as well as Sanctification. And not only that, the fact that Monergism is there, at any stage, would still cause a problem with the 6th Ecumenical council. And so some difficulties remain.

Testing to see if this comment is approved.

I just saw that Robert said the samething, my bad!

Okay guys,

I am specifically responding to Robert. Canadian is just laying out assertions (all of which have been answered by Dr. Sh., which can found on my blog), and given that I have precious few minutes each day on the internet, I must use them wisely.

Robert,

I am not denying the Reformed faith is monergistic. My point was that the discussion is more complex than that. That’s all. Of course your quotes prove we teach mongerism. Who would deny it? But I am thinking you have the tendency to lump the whole package under the label of “regeneration,” and it’s more than that.

Jacob my dear (local) friend, you say:

“Of course your quotes prove we teach mongerism. Who would deny it? But I am thinking you have the tendency to lump the whole package under the label of “regeneration,” and it’s more than that.”

Your first 2 sentences concede Robert’s point (per his Reformed quotes). But your 3rd withdraws what you’ve granted per the same quotes…which concern Perseverance of the saints. While some Reformed exegets allow Sanctification in the Spirit a qualified “Synergistic” element — the Reformed Standards are “monergistically clear” — as Robert has repeatedly taken pains to show. This whole business of partisioning off Regeneration from Sanctification, yet holding to an a priori monergism does make for some real difficulties. Not the least of which is the Fathers belief that Salvation is an Organic whole — a rational humanity in God’s image and likeness, is genuinely Transformed into a righteousness Flock & Bride, that has true communion with God the Father, Son and Spirit. Why strain with an anthoropology that mucks this up for no good reason?

If it appears that my response is “all over the place,” it is because, as noted earlier, I only ahve minutes to write.

My point was this: Yes, we believe God is sovereign over the entire process (and over all of human reality, otherwise we are left with Open Theism). However, there is a *logical* (which may or may not overlap with *temporal*) distinction between regeneration and conversion. Shedd, Shaw, and numerous divines have made this clear.

Robert, since perserverance of the saints has come up so much, maybe it’s deserving of a deeper analysis from an EO perspective? And it’s tied into the whole matter of “assurance.” It always did confuse me that I was told I could (should!) have assurance of my salvation…but could not have assurance of my election. Catholics and others were said to be mired in a system where they had to dread the wrath of God because they could never be sure they were saved. I met some who’d left the Reformed faith because they became mired in worry that they were not elect. I was told that THOSE people simply were never really saved at all.

Dear BT,

Welcome to the OrthodoxBridge!

I think your suggestion about a future posting is worth pursuing. For now I’ll give you a short answer which is for Orthodoxy the eternal destiny of individuals is a mystery. If we are repentant like the Prodigal Son in Luke 15 and want to come home and are walking towards home the Father will be waiting for us. In Orthodoxy the stress is on repentance — turning away from sin and turning towards God “who is good and loves mankind.” That quote is from the closing line of the Orthodox Liturgy. I hear it every Sunday and for me that is the assurance of salvation.

I’ve often run into that quandry. Apparently, from what I’ve been told by a number of Reformed preachers, so did the Puritans — many despaired of salvation on their deathbeds, even though they fully held to the Perseverance (sorry for the lack of citations, I heard about this in sermons).

In the end, though, and I think Robert is saying this in his last line, we all trust in the mercy of God: we are “unworthy servants” who shouldn’t be expecting praise for doing what we are supposed to be doing (as Jesus says in one of his parables). Rather, we rest in the fact that God became man to save us.

This is better than trying to access whether or not I’m elect or have cooperated enough with God (can we ever?): He is merciful and so I cling to Him. God help me, and all of us, to do just that!

Russ

“Some without fulfilling the commandments think that they possess true faith. Others fulfill the commandments and then expect the Kingdom as a reward due to them. Both are mistaken.”

Saint Mark the Ascetic

That was more true of a *some* American Puritans, if Perry Miller’s narrative is to be believed (which it probably isn’t, great writer though he be). It wasn’t true of the Continental Reformed and certainly wasn’t true of the English and Scottish Puritans (otherwise they would have written a whole chapter on it in the Confession!).

The Reformed view is that Christ is the mirror of election–we look to Christ to know if we are saved. Of course, our Romanist friends, courtesy of Trent, will say I will burn in hell forever for believing in assurance, 1 John notwithstanding.

I was under the impression it was American Puritans *late* in the experiment, as it were.

Russ

PS– Is the caricature of the “Romanists” helpful to the discussion?

That was an exact quote from the Council of Trent. Not sure how it is a “caricature.”

Back to the point: Sinclair Ferguson’ class on the Confession, available for free on ItunesU, has a helpful section on explaining what assurance is and isn’t–and that is precisely *why* Rome anathematized it (so yes, my “caricature,” or exact quote, is relevant: Rome–and others–view assurance as contingent on the work of salvation *in* us, which of course is never complete; ergo, no assurance).

Yes, my referencing Rome was directly relevant.

I’m not trying to start a fight. You didn’t quote anything, though, so it isn’t an “exact quote.” Nor did you cite it. Do they hold to Trent slavishly? Does the current Catechism soften or harden this? What about Vatican II? There are many things to make up the Catholic position.

I also never said your referencing Rome was irrelevant either. Please realize that I’m not against you; but I am against holding something up as a position without at least actually quoting it or citing it in some form.

Russ

Bayou,

The anathema’s of Trent are for the solemn excommunication from the bosom of the Church. Protestants do not come under Catholic anathema’s, though the dogma which is anathematized is clearly rejected. Even the anathema’s are not sentences to hell but a turning over to Satan of those Catholic’s who refuse to deny the said doctrine. Protestant’s are now considered “separated brethren” and would be expected to reject those doctrines if converting but are not under the sentence of the anathema’s.

Trent says: “CANON XVI.-If any one saith, that he will for certain, of an absolute and infallible certainty, have that great gift of perseverance unto the end,-unless he have learned this by special revelation; let him be anathema.”

Can you tell me that you have infallible certainty of your election and perseverance?

sure, why not

How many times as a Calvinist did I watch someone who went years with this so called infallible assurance only to walk away from Christ, and our in house boys, including me, would blithely spout……”Maybe he was never justified. After all, we don’t know who the elect are.”

St. John says that he who has the Son has life, he who does not have the Son of God does not have life and this life is in his Son….I write you these things…..that you may know you have eternal life. Abiding in the vine brings forth fruit, but every branch in him that does not bring forth fruit is cast forth and withers.

As Karen and Jnorm mentioned, it is through real communion with Christ that we have assurance but not infallible or presumptious assurance. We trust Christ’s promises about salvation in him, but then we rush to participate in and enjoy that salvation.

WCF 18 reveals how tenuous your assurance is. “Although hypocrites and other unregenerate men may vainly deceive themselves with false hopes…..of being in the favour of God and estate of salvation…….and a believer may wait long, and conflict with many difficulties before he be a partaker of it.”

You do not know the secret election of God in the decree, yet WCF touts infallible assurance…..well, later on…..hopefully….if you strive to know it…..and look inward (not just outward to Christ) for evidence of those graces…..and the Spirit’s burning in the bosom.

So much for infallible Calvinistic assurance.

You seem so concerned to assure yourselves of heaven when you die as a defence of the individual election you promote, but as Orthodox we are more concerned with enjoying heaven and Christ now in our prayer corners and in the services and sacraments, whose kingdom is within. Our prayers and services always repeat “now and ever and unto ages of ages, amen.” All our worship is eschatological (“both now and ever”) and Christ is “everywhere present filling all things.” Our assurance and hope is based on his mercy alone, not on trying to ward off unbelief or doubt about a decree that you are really not sure of in the end.

At least Rome believes in a Real union with Christ. If a group doesn’t believe in a real union with Christ then what’s the point of even talking about assurance? For what do you really have assurance in? Assurance that you are infallibly of the elect apart from being in union with Christ?

At the end of the day, isn’t this somewhat Docetic? Somewhat gnostic?

You got me: I am a gnostic.

Rome might claim to believe in union with Christ, but as Orthodox scholar David Bradshaw has ably demonstrated, they don’t really (since they believe in both absolute divine simplicity and created grace; cf. Aristotle East and West).

On to a more serious note, I was simply explicating a historical point Russ made. I really don’t have time to use up mental energy or answer these questions if y’all don’t answer mine, like the definitions of person, motion, nature, ousia, hyperousia, etc. Fair enough?

On the question of assurance of salvation in Orthodoxy:

From 1 John 3:

“18 My little children, let us not love in word or in tongue, but in deed and in truth. 19 And by this we know[d] that we are of the truth, and shall assure our hearts before Him. 20 For if our heart condemns us, God is greater than our heart, and knows all things. 21 Beloved, if our heart does not condemn us, we have confidence toward God.”

I suspect this is some of the basis for the view that assurance is based on the work of salvation *in* us.

It seems to me that vis-a-vis most forms of Protestantism, Orthodoxy has a more dynamic, concrete, and experiential (as opposed to static, conceptual and theoretical) way of talking about personal “salvation.” (I can’t speak to Roman Catholicism, because I have never been one and am not familiar with RC theology–but suspect that in terms of theologically speaking more conceptually than experientially and concretely, it tends to be more like Protestantism in this way. Someone more knowledgable can correct me if I’m wrong.)

From an Orthodox perspective, salvation as we experience it (or appropriate it personally) on earth is a *process* that for most of us will be incomplete at the point of our death. IOW, what Protestants distinguish as “sanctification” is part and parcel of the larger “salvation” spoken of within Orthodoxy that includes the objective finished work of Christ (where I can say I *have been* saved) and the consummation of our salvation at the end of all things (where by God’s grace I *will be* finally saved), but which, most often, is speaking specifically about what Protestants understand as the process of our sanctification (where I *am being* saved). I have been taught that the Gk. words for “salvation” and “sanctification” in Scripture, where these various aspects of our salvation are discussed, are identical in whatever context, and I have found this is closer to how the Orthodox also speak about “salvation”–it is all-encompassing.

Typically, Orthodox do not talk in the abstract or presume to know about any individual’s personal salvation at the Last Judgment (since this is something known in any absolute sense only to God), but only in the concrete sense about our *sanctification* here and now, and I believe this is how the Apostle John is addressing the issue in his epistle above. The degree of our assurance of our “salvation” in the sense of sanctification is certainly contingent on our actual (hopefully growing) capacity for self-giving love in the likeness of Christ’s. Also, because Orthodox believe in the true (if damaged) freedom of the human will, we believe it is possible for one of the faithful, having begun the journey of repentance, to choose later to walk away from his relationship with God, and if he persists (though God will always be ready to receive him gladly back in repentance if he changes his mind again), God will let him do so. This is the primary reason, as I understand it, that Orthodox refuse to presume “once saved, always saved,” but this does not mean we doubt that someone who continues faithfully working out their salvation within the Church will be ultimately saved by the mercy of Christ, despite the stumbles, sins and imperfections they may have.

Speaking as a former Protestant, the understanding of salvation as a concrete, dynamic, personal relationship of communion with Christ as well as the understanding of the inviolate nature of the freedom of the human will is one reason technically within Orthodoxy, there is no teaching of “assurance of salvation” in the facile Protestant sense (there are variations within Protestantism, so I’m speaking only to what I experienced here). In my Protestant experience, what happened is that my assent to my church’s Evangelical statement of faith vis-a-vis personal salvation along with a good-faith attempt to adhere to some basic level or standard of conduct deemed befitting such professed assent (accepted as “evidence” of the vitality of that faith only and not the condition for the free gift of “salvation”), “assured” me I was “saved” based on certain logical, presuppositional arguments from certain verses of Scripture deemed to support the doctrines my church taught. I realized, especially after I began exploring Orthodoxy, that what this Evangelical approach actually encouraged me to rest my confidence in was the Evangelical conceptual dogma I was taught–the Scriptural formulae and logical arguments from the texts of Scripture, if you will–and not actually the Person of Christ Himself as I experienced Him.

In contrast, what I found as I explored Orthodox teaching was that Orthodoxy encouraged me to rest my confidence only on the Truth of Who Christ is (and more especially it taught me how to begin to experience that Truth by coming into real communion with Him through prayer and the sacraments of the Church). Because of Orthodox teaching about the nature of the Substitutionary Atonement (*not* penal), the motivation of God in sending Christ to die for our sin (love/our healing and redemption, not the venting of His “wrath”), and the wounded, but not destroyed, true freedom of even the fallen human will, it is intuitively a no-brainer now to entrust myself to Christ and His mercy. I have discovered that is all the assurance I really need.

In Orthodoxy, we learn to think and speak very humbly with respect to ourselves only about what we can really know experientially and concretely and not to presume (which means we can only acknowledge that we are sinners unworthy of salvation). On the other hand, Orthodox teaching regarding the completely merciful nature of God and about our God-given freedom gives those of us who are faithfully engaged in the disciplines of the Church ample reason to be joyful and hopeful in our expectations of God’s ultimate deliverance, cleansing and mercy on the Day of Judgment as well. It is not a case of being constantly and neurotically fearful of the possibility of God’s torment and wrath on the Day of Judgment, but rather a sober realization that only a completely purified and repentant heart will be able to stand unveiled without torment in the Presence of such a God, whose love is unspeakably pure and without the taint of any sin. One of my favorite verses is another from 1 John 3:1-3:

“Behold what manner of love the Father has bestowed on us, that we should be called children of God![a] Therefore the world does not know us,[b] because it did not know Him. 2 Beloved, now we are children of God; and it has not yet been revealed what we shall be, but we know that when He is revealed, we shall be like Him, for we shall see Him as He is. 3 *And everyone who has this hope in Him purifies himself, just as He is pure.*

I looked up the definition of the Greek for the words the Apostle John uses for “know” in these passages (and in 1 John 5:13). The two words used do not seem to have the connotation of logical assumption or acquaintance with facts, but rather of perceptual awareness, i.e., it is rooted not in the conceptual, but the real. The same word used in 1 John 5:13 is used of God’s “knowing” of us and our works (as in Rev. 3:1). I would be interested in what Greek scholars out there would say concerning the implications of the tense the verb “know” is in, in the Greek of 1 John 5:13.

At least that is how I have processed my experiences and what I have been taught so far. For what it’s worth. . .

It’s also funny that I get labled “gnostic” by people whose tradition believes that Pseud0-Dionysius is a saint.

Read Maximus on sexual intercourse and sexual differences. It’s not different from occult manuals, given that sexual differentiation (not the act, but the differentiation) is tied with sin and he suggests in heaven there will be an overcoming of sexual differentiation.

Be careful throwing the gnostic term around.

It’s wonderful to see St. Dionysius mentioned on his feast day, even though the context of the comment is a bit inflammatory.

“Having learned goodness and maintaining continence in all things,

you were arrayed with a good conscience as befits a priest.

From the chosen Vessel you drew ineffable mysteries;

you kept the faith, and finished a course equal to His.

Bishop martyr Dionysius, entreat Christ God that our souls may be saved. “