The doctrine of double predestination is the hallmark of John Calvin and Reformed theology. (#1) It is the belief that just as God predestined his elect to eternal life in Christ, he likewise predestined (reprobated) the rest to hell.

With blunt frankness Calvin wrote:

We call predestination God’s eternal decree, which he compacted with himself what he willed to become of each man. For all are not created in equal condition; rather, eternal life is foreordained for some, eternal damnation for others (Institutes 3.21.5; Calvin 1960:926).

Double predestination was one of Calvin’s more controversial teachings and he wrote extensively to defend this belief. In the final edition of his Institutes, Calvin devoted some eighty pages to defending this doctrine. (#2) Despite its controversial nature, double predestination became the official position of the Reformed churches.

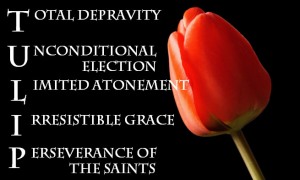

This blog posting will provide an Orthodox critique of Reformed theology. More specifically, it will focus on the doctrinal formula TULIP, because TULIP provides a clear and concise summary of Reformed theology. The acronym is a catchy way of conveying the five major points of the Canons of Dort: T = total depravity, U = unconditional election; L = limited atonement, I = irresistible grace, and P = perseverance of the saints.

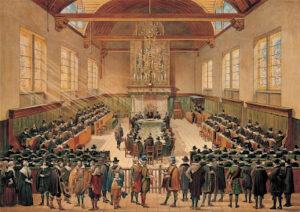

The Canons of Dort represent the Dutch Reformed Church’s affirmation of predestination in the face of the Remonstrant movement (popularly known as Arminianism) which attempted in the early 1600s to temper the rigor of predestination by allowing for human free will in salvation. (#3) Although the Canons of Dort form the official confession of the Dutch Reformed Church, its affirmation of predestination parallels that found in other major confessions, e.g., the Westminster Confession, the Second Belgic Confession, and the Heidelberg Catechism. (#4)

Calvinism and Eastern Orthodoxy represent two radically different theological traditions. Orthodoxy has its roots in the early Ecumenical Councils and the Church Fathers, whereas Calvinism emerged as a reaction to medieval Roman Catholicism. Aside from a brief encounter in the early seventeenth century, there has been very little interaction between the two traditions. (#5) This is beginning to change with the growing interest among Evangelicals and mainstream Protestants in Orthodoxy. (#6) This lacuna has often presented a challenge for Protestants in the Reformed tradition who wanted to become Orthodox and Orthodox Christians who want to reach out to their Reformed/Calvinist friends. This is why I created the OrthodoxBridge (see Welcome) and why I am tackling such difficult issues like the doctrine of predestination.

THE ORTHODOX CRITIQUE OF TULIP

This critique will consist of two parts: Part I (this blog posting) will critique the five points of TULIP and Part II (the next blog posting) will discuss Calvinism as an overall theological system.

The critique will proceed along four lines of argument:

(1) Calvinism relies on a faulty reading of Scripture,

(2) it deviates from the historic Christian Faith as defined by the Ecumenical Councils and the Church Fathers,

(3) its understanding of God’s sovereignty leads to the denial of the possibility of love, and

(4) it leads to a defective Christology and a distorted understanding of the Trinity.

T – Total Depravity

Total depravity describes the effect of the Fall of Adam and Eve on humanity. It is an attempt to describe what is otherwise known as “original sin.” Where some theologians believed that man retained some capacity to please God, the Calvinists believe that man was incapable of pleasing God due to the radical effect of the Fall on the totality of human nature. The Scots Confession took the extreme position that the Fall eradicated the divine image from human nature: “By this transgression, generally known as original sin, the image of God was utterly defaced in man, and he and his children became by nature hostile to God, slaves to Satan, and servants to sin.” (The Book of Confession 3.03; italics added) The Swiss Reformer, Heinrich Bullinger, taught that the image of God in Adam was “extinguished” by the Fall (Pelikan 1984:227).

The Canons of Dort asserted the universality and the totality of the Fall; that is, all of humanity was affected by the Fall and every aspect of human existence was corrupted by the Fall.

Therefore all men are conceived in sin, and are by nature children of wrath, incapable of saving good, prone to evil, dead in sin, and in bondage thereto; and without the regenerating grace of the Holy Spirit, they are neither able nor willing to return to God, to reform the depravity of their nature, or to dispose themselves to reformation (Third and Fourth Head: Article 3).

The Canons of Dort (Third and Fourth Head: Paragraph 4) went so far as to reject the possibility the unregenerate can hunger and thirst after righteousness on their own initiative. It insists this spiritual hunger is indicative of spiritual regeneration and only those who have been predestined for salvation will show spiritual hunger.

In taking this stance, the Canons of Dort reflected faithfully Calvin and the other Reformers’ understanding of the Fall. Calvin believed the Fall affected human nature to the point that man was even incapable of faith which is so necessary for salvation. He wrote:

Here I only want to suggest briefly that the whole man is overwhelmed–as by a deluge–from head to foot, so that no part is immune from sin and all that proceeds from him is to be imputed to sin (Institutes 2.1.9, Calvin 1960:253).

Martin Luther held to a similar radical understanding of original sin. At the Heidelberg Disputations, Luther asserted:

‘Free will’ after the fall is nothing but a word, and so long as it does what is within it, it is committing deadly sin (in Kittelson 1986:111; emphasis added).

The Reformed understanding of the Fall derives from Augustine’s interpretation of the story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. Augustine assumed that Adam and Eve were mature adults when they sinned. This assumption led to a more catastrophic understanding of the Fall. However, Augustine’s understanding represented only one reading of Genesis and was not reflective of the patristic consensus. Another reading of Genesis can be found in Irenaeus of Lyons, widely regarded as the leading Church Father of the second century. Irenaeus believed Adam and Eve were not created as fully mature beings, but as infants or children who would grow into perfection (Against the Heretics 4.38.1-2; ANF Vol. 1 p. 521). This foundational assumption leads to radically different theological paradigm. John Hick, in his comparison of Irenaeus’ theodicy against that of Augustine, notes:

Instead of the fall of Adam being presented, as in the Augustinian tradition, as an utterly malignant and catastrophic event, completely disrupting God’s plan, Irenaeus pictures it as something that occurred in the childhood of the race, an understandable lapse due to weakness and immaturity rather than an adult crime full of malice and pregnant with perpetual guilt. And instead of the Augustinian view of life’s trials as a divine punishment for Adam’s sin, Irenaeus sees our world of mingled good and evil as a divinely appointed environment for man’s development towards perfection that represents the fulfilment of God’s good purpose for him (1968:220-221).

Many Calvinists may find Irenaeus’ understanding of the Fall bizarre. This is because Reformed theology, like much of Western Christianity, has become so dependent on Augustine that it has become provincial and isolated in its theology.

One of the key aspects of the doctrine of total depravity is the belief that the Fall deprived humanity of any capacity for free will rendering them incapable of desiring to do good or to believe in God. Yet a study of the early Church shows a broad theological consensus existed that affirmed belief in free will. J.N.D. Kelly in his Early Christian Doctrine notes that the second century Apologists unanimously believed in human free will (1960:166). Justin Martyr wrote:

For the coming into being at first was not in our own power; and in order that we may follow those things which please Him, choosing them by means of the rational faculties He has Himself endowed us with, He both persuades us and leads us to faith (First Apology 10; ANF Vol. I, p. 165).

Irenaeus of Lyons affirmed humanity’s capacity for faith:

Now all such expression demonstrate that man is in his own power with respect to faith (Against the Heretics 4.37.2; ANF Vol. I p. 520).

Another significant witness to free will is Cyril of Jerusalem, Patriarch of Jerusalem in the fourth century. In his famous catechetical lectures, Cyril repeatedly affirmed human free-will (Lectures 2.1-2 and 4.18, 21; NPNF Second Series Vol. VII, pp. 8-9, 23-24). Likewise, Gregory of Nyssa, in his catechetical lectures, taught:

For He who holds sovereignty over the universe permitted something to be subject to our own control, over which each of us alone is master. Now this is the will: a thing that cannot be enslaved, being the power of self-determination (Gregory of Nyssa, The Great Catechism, MPG 47, 77A; in Gabriel 2000:27).

Another patristic witness against total depravity can be found in John of Damascus, an eighth century Church Father famous for his Exposition of the Catholic Faith, the closest thing to a systematic theology in the early Church. John of Damascus explained that God made man a rational being endowed with free-will and as a result of the Fall man’s free-will was corrupted (NPNF Series 2 Vol. IX p. 58-60). Saint John of the Ladder, a sixth century Desert Father, in his spiritual classic, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, wrote:

Of the rational beings created by Him and honoured with the dignity of free-will, some are His friends, others are His true servants, some are worthless, some are completely estranged from God, and others, though feeble creatures, are His opponents (1991:3).

Thus, Calvin’s belief in total depravity was based upon a narrow theological perspective. His failure to draw upon the patristic consensus and his almost exclusive reliance on Augustine resulted in a soteriology peculiar to Protestantism. However great a theologian Augustine may have been, he was just one among many others.

An important aspect of Orthodox theology is the patristic consensus. Doing theology based upon the consensus of the Church Fathers and the seven Ecumenical Councils reflects the understanding among the early Christians that they shared a common corporate faith. This approach is best summed up by Vincent of Lerins: “Moreover, in the Catholic Church itself, all possible care must be taken, that we hold that faith which has been believed everywhere, always, by all.” (A Commonitory 2.6; NPNF Second Series, Volume XI, p. 132). See also, Irenaeus of Lyons’ boast to the Gnostics: “…the Church, having received this preaching and this faith, although scattered through the whole world, yet, as if occupying but one house, carefully preserves it (Against the Heretics 1.10.2, ANF Volume I, p. 331).

Thus, when the Orthodox Church confronted Calvinism in the 1600s, it already had a rich theological legacy to draw upon. Decree XIV of Dositheus’ Confession rejects the Calvinist belief in total depravity, affirming the Fall and humanity’s sinful nature, but stops short of total depravity.

We believe man in falling by the [original] transgression to have become comparable and like unto the beasts, that is, to have been utterly undone, and to have fallen from his perfection and impassibility, yet not to have lost the nature and power which he had received from the supremely good God. For otherwise he would not be rational, and consequently not man; but to have the same nature, in which he was created and the same power of his nature, that is free-will, living and operating (Leith 1963:496; emphasis added).

The Orthodox Memorial Service has a line that sums up the Orthodox Church’s understanding of the Fall: “I am an image of Your indescribable glory, though I bear the scars of my sins” (Kezios 1993:46). In summary, the Orthodox Church’s position is that human nature still retains some degree of free will even though subject to corruption by sin.

Biblical support for the Orthodox understanding of fallen human nature can be found in Paul’s speech to the Athenians. He commends the Athenians for their piety, noting they even had an altar dedicated to an unknown deity. Although their fallen nature prevented them from making full contact with the one true God, they nonetheless retained a longing for communion with God. Paul takes note of the spiritual longing that underlay the Athenians’ religiosity using it as a launching point for the proclamation of the Gospel:

From one man he made every nation of men, that they should inhabit the whole earth; and he determined the times set for them and the exact places where they should live. God did this so that men would seek him and perhaps reach out for him and find him, though he is not far from each one of us (Acts 17:26-27; emphasis added).

What Paul says here flies in the face of the Canons of Dort’s assertion that the unregenerate were incapable of spiritual hunger. Peter took a similar approach in his speech to Cornelius the Gentile centurion notes:

I now realize how true it is that God does not show favoritism but accepts men from every nation who fear him and do what is right (Acts 10:34-5).

Peter and Paul’s belief in God’s love for the nations is not a new idea. The Gentiles’ capacity to respond to God’s grace is a recurring motif in the Old Testament. Alongside Israel’s divine election was the theme of Yahweh as Lord of the nations in the Old Testament (see Verkuyl 1981:37 ff.)

It is important to keep in mind that the doctrine of election — the elect status of the Jewish people — is key to understanding Jesus’ messianic mission and much of Paul’s letters. Contrary to the expectations of many of the Jews of the time, Jesus’ messianic calling involved his bringing the Gentiles into the kingdom of God. This was a revolutionary doctrine — that the Gentiles could become saved through faith in the Messiah apart from becoming Jewish. This precipitated a theological crisis over the doctrine of election that underlie Paul’s reasoning in Romans and Galatians. In Romans 9-11, Paul had to explain and uphold God’s calling of Israel in the face of the fact that Israel had rejected the promised Messiah. To read the Calvinist understanding of double predestination into Romans 9 constitutes a colossal misreading of what Paul was attempting to do. Furthermore, it overlooks the great reversal of election that took place in the former Pharisee Paul’s thinking: the non-elect — the Gentiles — receive the grace of God and the elect — the nation of Israel — are rejected (Romans 10:19-21).

U – Unconditional Election

Whereas the first article of TULIP describes our fallen state, the second article describes God, the author of our salvation. The emphasis here is on the transcendent sovereignty of God whose work of redemption is totally independent of human will.

That some receive the gift of faith from God, and other do not receive it, proceeds from God’s eternal decree (Canons of Dort First Head: Article 6)

Calvin likewise affirms unconditional election through his rejection of the idea that our election is based on God’s foreknowing our response. He writes:

We assert that, with respect to the elect, this plan was founded upon his freely given mercy, without regard to human worth; but by his just and irreprehensible but incomprehensible judgment he has barred to door of life to those whom he has given over to damnation (Institutes 3.21.7, Calvin 1960:931; see also Institutes 3.22.1, Calvin 1960:932).

In another place, Calvin uses a medical analogy to describe double predestination:

Therefore, though all of us are by nature suffering from the same disease, only those whom it pleases the Lord to touch with his healing hand will get well. The others, whom he, in his righteous judgment, passes over, waste away in their own rottenness until they are consumed. There is no other reason why some persevere to the end, while others fall at the beginning of the course (Institutes 2.5.3; Calvin 1960:320).

Although the doctrine of total depravity is listed first, it is not the logical starting point of TULIP. The real starting point is in the second article, unconditional election. God’s transcendent sovereignty is the true starting point of Calvin’s soteriology. Karl Barth argued that it is Calvin’s insistence on God’s absolute sovereignty which characterizes Calvin’s theology; double predestination is but a logical outworking of this fundamental premise (Barth 1922:117-118).

The Calvinist doctrine of unconditional election is at odds with the Church Fathers who taught that predestination is based upon God’s foreknowledge. John of Damascus wrote:

We ought to understand that while God knows all things beforehand, yet He does not predetermine all things. For He knows beforehand those things that are in our power, but He does not predetermine them. For it is not His will that there should be wickedness nor does He choose to compel virtue. So that predetermination is the work of the divine command based on fore-knowledge. But on the other hand God predetermines those things which are not within our power in accordance with His prescience (NPNF Series 2 Vol. IX p. 42).

Another Church Father, Gregory of Palamas, asserted the same principle:

Therefore, God does not decide what men’s will shall be. It is not that He foreordains and thus foreknows, but that He foreknows and thus foreordains, and not by His will but by His knowledge of what we shall freely will or choose. Regarding the free choices of men, when we say God foreordains, it is only to signify that His foreknowledge is infallible. To our finite minds it is incomprehensible how God has foreknowledge of our choices and actions without willing or causing them. We make our choices in freedom which God does not violate. They are in His foreknowledge, but ‘His foreknowledge differs from the divine will and indeed from the divine essence.’ (Gregory of Palamas’ Natural, Theological, Moral and Practical Chapters, MPG 150, 1192A; Gabriel 2000:27).

Supported by the patristic consensus, the Orthodox Church in the Confession of Dositheus in no uncertain terms condemns the Calvinist doctrine of unconditional election.

But to say, as the most wicked heretics–and as is contained in the Chapter answering hereto-that God, in predestinating, or condemning, had in no wise regard to the works of those predestinated, or condemned, we know to be profane and impious (Decree III; Leith 1963:488).

L – Limited Atonement

One of the more controversial assertions in the Canons of Dort is the doctrine of limited atonement — that Christ died only for the elect, not for the whole world.

…it was the will of God that Christ by the blood of the cross, whereby He confirmed the new covenant, should effectually redeem out of every people, tribe, nation, and language, all those, and those only, who were from eternity chosen to salvation and given to Him by the Father (Second Head: Article 8; emphasis added).

Whereas the Canons of Dort is explicit in its affirmation of limited atonement, surprisingly a careful reading of Calvin’s Institutes does not yield any explicit mention of limited atonement (see Roger Nicole’s article).

There are a number of biblical passages that can be used to refute the doctrine of limited atonement. Biblical references commonly used to challenge the Calvinist position tend to be those that teach God’s desire for all to be saved, e.g., John 3:16:

For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life (emphasis added).

Another important passage is I Timothy 2:3-6:

This is good, and pleases God our Savior, who wants all men to be saved and come to a knowledge of the truth. For there is one God and one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus, who gave himself as a ransom for all men…. (emphasis added)

Another significant passage that specifically challenges the notion of limited atonement is I John 2:2:

He is the atoning sacrifice for our sins, and not only for ours but also for the sins of the whole world (emphasis added).

This passage is especially relevant for two reasons: (1) it specifically refers to Christ’s atoning death on the Cross, and (2) it teaches that Christ died not just for the elect (us) but also for the non-elect (the whole world). Calvin cited I John 2:2 three times, but what is surprising is that nowhere in his Institutesdid Calvin deal with the latter part of the verse. (The Biblical Reference index in the back of the Institutes (McNeill, ed.) shows that I John 2:2 is cited three times: 2.17.2, 3.4.26, and 3.20.20.)

The real challenge for those who appeal to the above passages lies in the semantic tactics used by Calvinists in which they argue that “all” and “the world” are not to be taken literally but as referring to only those predestined for salvation. (#7) Zacharias Ursinus, the German Reformer, understood “all” to refer to “all classes” rather than to individuals (Pelikan 1984:237). Similarly, Theodore Beza, Calvin’s colleague and successor, insisted that John 3:16 applied only to the elect. Roger Nicole’s explanation describes well the Calvinist strategy for reading biblical texts:

For instance, “all” may vary considerably in extension: notably “all” may mean, all men, universally, perpetually and singly, as when we say “all are partakers of human nature”; or again it may have a broader or narrower reference depending upon the context in which it is used, as when we say “all reached the top of Everest,” where the scope of the discourse makes it plain that we are talking about a group of people on which set out to ascend the mountain. It is not always easy to determine with assurance what is the frame of reference in view: hence controverted interpretations both of Scripture and of individual theologians. (emphasis added)

This hermeneutical approach imparts a certain imperviousness to Reformed theology; one either accepts their semantic perspective or one does not. The inductive method will not work here. This means that effective refutation of Calvinism cannot be carried out solely on the grounds of biblical exegesis. This longstanding impasse in Protestantism is an example of sola scriptura’s inability to create doctrinal unity on fundamental issues.

This is where historical theology can help us assess the competing truth claims. The advantage of historical theology is two-fold: (1) it enables us to understand the historical and social forces that shaped Calvinists’ exegesis and (2) it enables us to determine the extent to which Calvin’s theology reflected the mainstream of historic Christianity or to what extent Calvin’s theology became deviant and heretical.

Historical theology shows there existed a widespread belief among the Church Fathers in God’s universal love for humanity. Irenaeus of Lyons wrote.

For it was not merely for those who believed on Him in the time of Tiberius Caesar that Christ came, nor did the Father exercise His providence for the men only who are now alive, but for all men altogether, who from the beginning, according to their capacity, in their generation have both feared and loved God, and practised justice and piety towards their neighbours, and have earnestly desired to see Christ and to hear his voice (Against the Heretics 4.22.2).

St. John of the Ladder wrote:

God belongs to all free beings. He is the life of all, the salvation of all–faithful and unfaithful, just and unjust, pious and impious, passionate and dispassionate, monks and laymen, wise and simple, healthy and sick, young and old–just as the effusion of light, the sight of the sun, and the changes of the seasons are for all alike; ‘for there is no respect of persons with God.’ (1991:4)

The universality of Christ’s redeeming death can be found in the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, used on most Sundays in the Orthodox Church. During the words of institution over the bread and the wine, in one of the inaudible prayers, the Orthodox priest will pray a paraphrase of John 3:16:

You so loved Your world as to give Your only-begotten Son, that whoever believes in Him should not perish but have eternal life. …. Having come and having fulfilled the divine plan for us, on the night when He was delivered up, or rather gave Himself for the life of the world…. (Kezios 1996:24; emphasis added).

Probably the most resounding affirmation of this can be found at the end of each Sunday Liturgy when the priest concludes: “…for He alone is good and He loveth mankind.” (Kezios 1993:41)

I – Irresistable Grace

The fourth article attributes our faith in Christ to God’s effectual calling. The Canons of Dort stresses that God “produces both the will to believe and the act of believing also” (Third and Fourth Head: Article 14; see also Article 10). Faith in Christ is not the result of our choosing or our initiative, but is solely from God.

And as God Himself is most wise, unchangeable, omniscient, and omnipotent, so the election made by Him can neither be interrupted nor changed, recalled, or annulled; neither can the elect be cast away, nor their number diminished (Canon of Dort First Head: Article 11).

Furthermore, the Canons of Dort rejects the teaching that God’s converting grace can be resisted. The Third and Fourth Head: Paragraph 8 condemns the following statement: “That God in the regeneration of man does not use such powers of His omnipotence as potently and infallibly bend man’s will to faith and conversion….” Our free will has no bearing on our having faith in Christ. Faith in Christ is purely by the grace of God.

Although Calvin did not teach with the same starkness as the Canons of Dort the doctrine of irresistible grace, we find indications in his Institutes that he believed in the underlying idea. He wrote of God’s election being “inviolable” (Institutes 3.21.6, Calvin 1960:929), God’s unchangeable plan being “intrinsically effectual” for the salvation of the elect (Institutes 3.21.7; Calvin 1960:931); and God as the “intrinsic cause” of spiritual adoption (Institutes 3.21.7; Calvin 1960:941). Probably the closest we can find to an explicit endorsement of irresistible grace is Calvin’s paraphrase of Augustine.

There Augustine first teaches: the human will does not obtain grace by freedom, but obtains freedom by grace; when the feeling of delight has been imparted through the same grace, the human will is formed to endure; it is strengthened with unconquerable fortitude; controlled by grace, it never will perish, but, if grace forsake it, it will straightway fall…. (Institutes 2.4.14; Calvin 1960:308).

These passages lead to the conclusion that Calvin and the Synod of Dort shared the same belief in irresistible grace.

Orthodoxy rejects the doctrine of irresistible grace because this doctrine assumes the absence of human free will. The early Church Fathers — as noted in the section on total depravity — affirmed the role of free will in our salvation. One of the earliest pieces of Christian literature, the second century Letter to Diognetus, contains a clear affirmation of human free will and a rejection of salvation by compulsion. The author writes concerning the Incarnation:

He sent him as God; he sent him as man to men. He willed to save man by persuasion, not by compulsion, for compulsion is not God’s way of working (Letter to Diognetus 7.4; Richardson 1970:219).

Ultimately, the underlying flaw of Reformed soteriology is the emphasis on God’s sovereignty to the denial of love. The Calvinist insistence on God’s sovereignty undercuts the ontological basis for the human person. Closer inspection of the doctrine of irresistible grace brings to light a certain internal contradiction in Reformed theology: God’s free gift of grace is based on compulsion. Or to put it another way: How can a gift be free if there’s no freedom of choice? Love that is not free cannot be love. Love must arise from free choice. Bishop Kallistos Ware writes:

Where there is no freedom, there can be no love. Compulsion excludes love; as Paul Evdokimov used to say, God can do everything except compel us to love him (Ware 1986:76; emphasis in original).

Where there is no free will, there is no genuine love, nor can there be genuine faith. This in turn subverts and overthrows the fundamental Protestant dogma of sola fide. Ironically, Calvinism’s crowning glory also happens to be its fatal flaw.

Another reason why Calvinism is incompatible with Orthodoxy is its implicit monotheletism.In the seventh century, there arose a controversy as to whether Christ had one will or two. Monotheletism asserted that Christ had only one will (the divine) and bitheletism affirmed that Christ had two wills (human and divine working in harmony). The Sixth Ecumenical Council (Constantinople III) rejected monotheletism in favor of bitheletism. For an informed discussion of the theological debates surrounding the monotheletism heresy see Jaroslav Pelikan’s The Spirit of Eastern Christendom Vol. 2 (1973).

The Calvinists’ denial of human free will and their insistence on the dominance of the divine will over human will parallels the heresy of monothelitism, which insisted that Christ did not have two wills: a human will and a divine will. This assertion is made on the basis that the doctrine of the Incarnation rests on what constitutes the divine nature and what constitutes human nature. A defective anthropology (e.g., the denial of free will or the importance of physical flesh) leads to a defective Christology. Thus, the Reformed tradition’s implicit monotheletism points to a defective Christology and a significant departure from the historic Faith as defined by one of the Seven Ecumenical Councils.

P – Preservation of the Elect

Also known as the Perseverance of the Saints, the fifth article in TULIP addresses the troubling issue of Christians backsliding or falling into sin. Their failure to display the marks of election would seem to call into question the effectiveness of divine election. Again, we find the emphasis on God’s sovereignty:

Thus it is not in consequence of their own merits or strength, but of God’s free mercy, that they neither totally fall from faith and grace nor continue and perish finally in their backsliding; which, with respect to themselves is not only possible, but would undoubtedly happen; but with respect to God, it is utterly impossible, since His counsel cannot be changed nor His promise fail; neither can the call according to His purpose be revoked, nor the merit, intercession, and preservation of Christ be rendered ineffectual, nor the sealing of the Holy Spirit be frustrated or obliterated (Canons of Dort Fifth Head: Article 14).

Similarly, in response to questions about the status of the lapsed, Calvin’s position was: the elect cannot fall from salvation, even after their conversion, they will inevitably be saved (Institutes 3.24.6-7, Calvin 1960:971-3). Calvin writes:

For perseverance itself is indeed also a gift of God, which he does not bestow on all indiscriminately, but imparts to whom he pleases. If one seeks the reason for the difference–why some steadfastly persevered, and others fail out of instability–none occurs to us other than that the Lord upholds the former, strengthening them by his own power, that they may not perish; while to the latter, that they may be examples of inconstancy, he does not impart the same power (Institutes 2.5.3; Calvin 1960:320).

One could say crudely that the elect will be saved against their will, but the more nuanced approach is to say that the elect will inevitably choose to be saved because that desire has been implanted in them by God.

In contrast to Calvinism, the Orthodox understanding of the perseverance of the saints is based upon synergy — our cooperation with God’s grace, and deification — our becoming partakers in the divine nature. The Confession of Dositheus affirms the synergistic approach to salvation in contrast to the monergistic approach found in the Reformed confessions.

And we understand the use of free-will thus, that the Divine and illuminating grace, and which we call preventing grace, being, as a light to those in darkness, by the Divine goodness imparted to all, to those that are willing to obey this-for it is of use only to the willing, not to the unwilling-and co-operate with it, in what it requireth as necessary to salvation, there is consequently granted particular grace; which, co-operating with us, and enabling us, and making us perseverant in the love of God, that is to say, in performing those good things that God would have us to do, and which His preventing grace admonisheth us that we should do, justifieth us, and makes us predestinated (Leith 1963:487-8; emphasis added).

Irenaeus likewise teaches the perseverance of the saints, but from the perspective of theosis.

…but man making progress day by day, and ascending towards the perfect, that is, approximating to the uncreated One. …. Now it was necessary that man should in the first instance be created; and having been created, should receive growth; and having received growth, should be strengthened; and having been strengthened, should abound; and having abounded, should recover [from the disease of sin]; and having recovered, should be glorified; and being glorified, should see His Lord (Against the Heretics 4.38.3; ANF Vol. I p. 522).

The Orthodox approach to salvation provides the basis for a relational approach to salvation as opposed to the more forensic and mechanistic approach found in Western theology. This provides the basis for salvation as union with Christ and salvation as life in the Trinity.

Robert Arakaki

#1 Although closely related, Calvin and Calvinism are not synonymous. The relationship between Calvin and Reformed theology is more complex than most people realize. As a matter of fact, Alister McGrath warns against equating the two (1987:7). Also, it should be noted that some would dispute the centrality of predestination for Calvin’s theology. McGrath describes it as being an “ancillary doctrine, concerned with explaining a puzzling aspect of the consequence of the proclamation of the gospel of grace” (1990:169).

#2 See the edition by John T. McNeill (ed.) 3.21-25. For a discussion of the growing prominence of the doctrine in the successive editions of Calvin’s Institutes see Pelikan 1984:217-220.

#3 For a discussion of the theological issues at stake in the Remonstrant/Reformed controversy see Pelikan 1984:232-244.

#4 Unlike Lutheranism with its Formula of Concord, the Reformed tradition has no confessional statement with a similar normative stature (Pelikan 1984:236).

#5 In the early seventeenth century, the Patriarch of Constantinople, Cyril Lucaris, came under the influence of Reformed theology. In response to the challenge of Calvinism, the Orthodox Church responded by swiftly deposing Cyril, followed by convening a synodal gathering in Jerusalem. At that council, Calvinism was formally repudiated through The Confession of Dositheus, composed by the Patriarch of Jerusalem by that name (in Leith 1963:486-517. Thus, for Orthodoxy Calvinism is not a theological option.

#6 See Bradley Nassif’s, “Will the 21st be the Orthodox Century?” in Christianity Today (December 2006).

#7 Medieval Catholic theologians who sought to defend double predestination in the face of I Timothy 2:4 would employ a more philosophical line of defense. They drew upon the distinction between God’s “antecedent will” and his “ordinate will” (Pelikan 1984:34).

References

Robert,

I saw your post linked at the Orthodox Collective and was intrigued by the title since I have had a longstanding interest in the similarities and differences between Orthodoxy and other faith traditions (in general) and finding a satisfactory treatment of Calvinism from an Orthodox perspective. I was especially pleased to notice that you placed the Calvinist dependence on Bl. Augustine in the wider Western tradition, as I’ve noticed a similar theological bottleneck in the Catholic Church (Jerome>Augustine>Aquinas). I wonder if that makes Protestant sotierology any more or less peculiar than Catholic?

Also, when I went to read note #5, I was interested to learn about Cyril Lucaris but also surprised not to see discussion of the Lutheran-Orthodox exchange in between the Reformers and Patriarch Jeremias II since the result was a very early consideration of the differences you discuss. For an excellent article on the exchange, see http://www.stpaulsirvine.org/html/lutheran.htm.

May God bless you in your continued work!

Jon

Jon,

Thank you for your comments! With respect to your question about the “peculiarity” of Protestant soteriology, I would say that it cannot be considered catholic especially in light of its deviations from the patristic consensus. Much of Protestant theology are extensions of the medieval Roman Catholic tradition. You might find note #7 that mentioned Scholastic theology was used in defense of double predestination. I’m sure that the relationship between Protestant soteriology and the Western tradition would make for some interesting research!

I’m aware of the Lutheran-Orthodox dialogue that took place in the 1500s. For the most part I confine my focus to the Reformed tradition. Part of the reason is that this is a tradition I’m quite familiar with and for that reason can give it a fair and balanced treatment. I’m not as familiar with the Lutheran and the Anglican traditions. I can follow the discussions pretty closely but don’t feel that I’m in a position to write about these traditions in an open forum in a balanced and knowledgable manner.

Robert

“Thus, the Reformed tradition’s implicit monotheletism points to a defective Christology and a significant departure from the historic Faith as defined by one of the Seven Ecumenical Councils.”

Plucked!

I don’t think this section provides as much of a statement as it intends. It’s quite clear from Calvin’s Supralapsarian perspective that any denial of man’s free will is only in relation to God’s pre-ordaining of the fall and likewise pre-declaring salvation despite the incapacitated will of man. For the sinless Christ there wouldn’t need to be a fore-choosing of Christ’s will in agreement with the Divine will. Just as Calvin permits Adam to have had a “free will”, he would easily permit the same to Christ.

I won’t deny that this provides further questions and knots to untangle for Protestants at other places; And that it certainly deviates from other points of Orthodox tradition. But this accusation of montheletism is off-base when you supply a consistent set of Protestant presuppositions and don’t force Orthodox presupposition into Protestant theology.

Which is to say God decrees sin.

But if God has decreed man’s incapacity to be natural, then it is intrinsic and not apart from nature. So the fallen nature assumed by Christ would have this, and the incarnation is destroyed. Consubstantiality means he must assume exactly what we are by nature. If Adam had free will, Christ the second Adam had free will, but this is a natural faculty and not an extrinsic property decreed on persons selectively.

And to say that Christ’s nature is different from ours because he is sinless is untenable. He is sinless because he is a divine person and sin is not natural for his humanity because it is not natural for our humanity….they are the same humanity.

You’re still walking the same route within your paradigm. I do not disagree with your steps, simply that they don’t apply to the Protestant doctrine.

1) God did not need to decree man in incapacity (even within the Supralapsarian perspective) but decree by his capacity to fall. Remember that the Westminster Confession says: ” God from all eternity, did, by the most wise and holy counsel of His own will, freely, and unchangeably ordain whatsoever comes to pass; yet so, as thereby neither is God the author of sin, nor is violence offered to the will of the creatures; nor is the liberty or contingency of second causes taken away, but rather established.” So the incarnation is preserved in this way. Calvin works within this very idea for the rest of his discussion concerning “free will”, that while the technical liberty remaining the taint of sin perverts it such as to make it useless.

2) The above point makes moot most of the consubstantiality point. Thought Christ assumed our nature and Protestant can even say assumed our “fallen nature”, it will be without the guilt of Original Sin (purely Augustinian) and therefore without any of Calvin’s incapability for “free will” derived from the taint of sin.

3) Thus Christ assumes our very nature with its original and retained liberty of “free will”. Thus no Protestant would even need to step near your final straw man of “Christ’s nature is different from ours”.

I appreciate the dialogue and I recognize that a semblance of Calvin is found here but to think Protestants haven’t walked through these ideas often is odd.

I will concur that some Protestants do clearly re-find the heresy of monotheletism when they claim Christ couldn’t sin. But I’ve always returned to the Sixth Ecumenical Council when refuting and reproving them.

Joshua,

I appreciate your comments. I have a few questions about the Reformed understanding of free will and human nature. Does the Westminster Confession or any other major confessional statements affirm that free will is essential to human nature?

I noticed that chapter IX of the Westminster Confession affirms that man before the Fall possessed a free will and was able to fall from grace. I find it significant that chapter XVII denied that the elect could ever fall from the state of grace because their calling stem from the immutable decree of election. This makes me wonder: Does the Reformed tradition believe that salvation in Christ entails the restoration of human nature including free will? Or is free will a non-essential aspect of human existence? Just so we’re clear, by free will I mean our freedom and power to do what is good and pleasing to God (cf. Chapter IX of Westminster Confession).

My understanding is that unless the Reformed tradition can affirm the restoration of free will as integral to our salvation in Christ it becomes vulnerable to one of two criticisms: (1) the principle of correlation points to the divine will dominating the human will (implicit monotheletism) or (2) that Christ’s humanity is different from ours – his human will was truly free while ours remained constrained by external factors.

For Orthodoxy the Incarnation was more than a historical event. It provides the framework for the salvation of the human race. There is a saying by St. Maximus the Confessor: That which was not assumed (in the Incarnation) is not healed. Thus, the Christological teachings of the Ecumenical Councils have profound implications for how we understand our salvation in Christ.

Robert

I would like to comment on Calvin’s defective Christology. If you read the Institutes and the 12 anathamas of St. Cyril of Alexandria endorsed by the Third Ecumenical Council, the Council of Ephesus in 431, it quickly becomes apparent how similar Calvin’s Christology is to Nestorianism. Calvin also rejected the doctrine of the communication of attributes or the deification of the human nature of Christ. That is why Calvin did not believe that the bread and wine become the actual Body and Blood of Christ in the Eucharist. Instead, he believed that the body of Christ is in heaven. However, since the human nature of Christ was deified by its union with the divine nature, we can receive the Body of Christ when we partake of the Eucharist. Also if the human nature of Christ is deified, we who are united to Christ are also deified. Therefore his defective Christology effected his soteriology.

Fr. John W. Morris

I know it’s been a long time since the comment was made, but my reply is directed to Fr. John W. Morris, not anyone else.

I read the 12 Anathemas, and have studied the Institutes. Where is the “similarity to Nestorianism” which is equated to “defective Christology” ?

The way I understand Calvin’s view is that His human nature is not omnipresent. Therefore He could tell his disciples he was going somewhere, such as “to him who sent me”.

Yet He could also say, “And behold, I am with you always, to the end of the age”. So in one respect He left, but in another He is with us.

I don’t totally understand your doctrine of deification and when that happened, to the human nature of Christ. If you can explain that to me, maybe I can understand.

Matthew 26

26 Now as they were eating, Jesus took bread, and after blessing it broke it and gave it to the disciples, and said, “Take, eat; this is my body.”

—

I believe that he actually took bread. In my understanding it is actually bread. It looks like bread, tastes like bread, smells like bread. I believe He broke bread after He blessed it. I don’t believe He handed them his actual flesh. He had a reason to use bread.

We believe we “really” receive the body and blood of Jesus while the elements of bread and wine remain the same.

We believe:

He ascended into heaven, and sits at the right hand of God the Father Almighty: From thence he shall come to judge the quick and the dead:”

I don’t believe it is necessary for Him to leave His seat in Heaven for believers to truly feed upon the body and blood of Christ.

“The body which is born of the holy Virgin is in truth body united with divinity, not that the body which was received up into the heavens descends, but that the bread itself and the wine are changed into God’s body and blood.”

St John of Damascus OTOF Bk IV ch 13.

In the event recorded in Matthew 26, would you say that the body and blood of God was in two different places at once ?

Or would you say the body and blood of Jesus can be multi-local like Rome says ?

“But when the great and wonderous prayers have been recited, then the bread becomes the body and the cup the blood of our Lord Jesus Christ….When the great prayers and holy supplications are sent up, the Word descends on the bread and the cup, and it becomes His body. – Athanasius

I found this under the link: http://www.stseraphim.org/dcchapt6.html

“There are several consequences, results, or implications of this union of the two natures in Christ that are directly related to the question of our redemption. The first may be called the communion of attributes. The theologians use the Latin technical term ‘communicatio idiomatum’ to describe this consequence. It consists of the fact that in the Person of Christ, the two natures united without confusion, without change, without division and without separation, each of the natures transmitting its attributes to the other. In other terms, what belongs and is proper to Him as Man is attributed to Him as God. What is proper to Him as God is ascribed to Him as Man.”

Now, does this mean that we believe exactly as Rome does, this I cannot say because I don’t know Roman teaching well enough. Nor do I think this is the only thing to be said from the Orthodox perspective. I’m sure someone else has gone into the communication of attributes in greater detail. But as a short answer to your question, yes, we believe that “what belongs and is proper to Him as Man is attributed to Him as God. What is proper to Him as God is ascribed to Him as Man.”

John

Bryan,

I would also recommend you follow the link and read what else is written there. There’s much more information and I didn’t want to post it all here for the sake of brevity.

Bryan,

Christ does not need a change in location to make the bread and wine his body and blood. This is what He does by his divine energies. But this is also why we do not merely attribute things to Christ’s humanity in name only, but we affirm a real interpenetration of divine energies in that which is human.

Joshua,

A number of calvinists may not like the monothelite charge against them by a number of us orthodox, but I honestly don’t see how you guys can free yourself from this charge.

The reformed answers that you guys give only seem to prove our point.

The answers I see from the reformed only

I forgot to mention that classical monothelitism believed in the existance of two wills. The only difference was they thought the human will to be passive while the divine active. Thus the result was some form of determinism.

This is why I say I honestly don’t see how one can free Calvinism from this charge. For even if you jump start the will; that’s still a form Of monothelitism. Especially; If one stills. Keep. One trapped. Within some kind of determinism (regardless if you make use of the word free will)

Robert,

Just half-tongue-in-cheek:

You said:

“For Orthodoxy the Incarnation was more than a historical event. It provides the framework for the salvation of the human race. There is a saying by St. Maximus the Confessor: That which was not assumed (in the Incarnation) is not healed. Thus, the Christological teachings of the Ecumenical Councils have profound implications for how we understand our salvation in Christ.

Robert”

Since the Incarnation of the Logos assumed (took) male form, does this mean that only the male is healed? And the female was not healed? (Or, alternatively, was not in need of healing?)

I somehow think that you would not want to say this, but a strict, patriarchal, even misogynist reading of St Maximus could easily yield this answer.

Here, does monotheletism have “gender” as well?

Quo vadis your answer.

J.

John,

It’s important to understand what I say in the context of what the Orthodox Church teaches. I don’t think you will find any indications of misogyny in Orthodoxy, especially in light of honor we show to Mary the Theotokos. Mary is the Second Eve who undid the damage caused by the first Eve. The Incarnation involves both Mary and Jesus; it’s impossible to separate the two. You might not be aware of this but about now the Orthodox Church celebrates the Falling Asleep (Dormition) of the Theotokos. At the close of her life she was taken up into heaven and is now part of the heavenly host worshiping before the throne of God.

But let me quote from the Akathist Prayer:

O Sovereign Lady, Bride of God, spotless, blameless, pure and immaculate Virgin, thou who without stain, by thy glorious birth-giving, hast united God the Word to man, and joined the fallen nature of our race to heavenly things….

Hope this answers your half-tongue-in-cheek query. Ultimately, you can’t fully understand Orthodoxy through a careful parsing of what I write on my blog, you need to visit an Orthodox Church and listen to the Orthodox Liturgy. If there’s a church in your neighborhood celebrating the Falling Asleep of the Theotokos, I would encourage you to check out their services.

Robert

In past comments John demonstrated what appeared to be first hand knowledge of Orthodox liturgy and practice. Many of us who are “not yet on board” with Orthodoxy have indeed been to an Orthodox service (which is partly what drove me away).

Outlaw,

I am interested to learn what it was about Orthodox worship that drove you away. This may not be the best place to discuss it since I don’t want to hijack the thread but I’d be happy to learn your experience. You can contact me through my parish website. Thanks.

Dear Fr. John,

Welcome to the OrthodoxBridge! Thank you for your desire to reach out to inquirers like Outlaw and John.

Robert

No problem. The service was largely in Greek (which I could easily understand, given I am a lay linguist, but my wife is not). There were about three people there. Nobody seemed really interested. The kids were throwing model cars across the church during the celebration of the mysteries.

I know that doesn’t mean that Orthodoxy is wrong, but it also wasn’t the best spiritual atmosphere for my family.

John,

The Logos did not assume a man. He did not “assume” form but assumed substance/essence, though the fact that he is the eternal SON is significant in his recapitulation of Adam the first human “son of God”.

He assumes human nature in the person of the divine Son, not daughter. Eve herself is directly from Adam and man comes from woman, it is the same nature and Maximus somewhere discusses the healing of all the divisions of male and female in Christ.

The incarnation heals not the will of the male gender, but the faculty of nature which is instantiated in each person whether male of female.

John,

Saint Maximus adhered to the council of Chalcedon. The Council said(I’m paraphrasing) something about Jesus being consubstantial with the Father in his divinity and consubstantial with us in his humanity. One of the problems that the Fathers at Chalcedon had with Eutychis is that he made it seem as if Jesus was only consubstantial with the Theotokos, and not with us also.

I am saying this to let you know that we believe Jesus to be Consubtantial with both men and women for He is consubstantial with all of humanity.

However, we Orthodox don’t stop there for we have more to say in regards to the Kosmos in general.

John, you tend to do these hit and runs alot. I asked you a question on a different blog post about your back-ground. This is very important for it will allow people to talk to you instead of talking past you.

Outlaw,

I don’t believe Robert intends to imply that John has not

ever attended an Orthodox Divine Liturgy. I think his point

it only that it normally take several times at an Orthodox

Divine Liturgy for a Protestant to get past the unusual no-

velties…even if it is all in English. Deacon Michael Hyatt

suggests 12 or more Divine Liturgies in English to his parents,

family and friends…to make sure they have a good grasp of

what’s going on.

This means attending (as I seem to recall you indicating for

yourself) two to four Divine Liturgies, mostly in Greek at a

struggling ethnic greek church with 8-12 old greek/ethnic

faithful hanging on — is not likely a good place or way to get

your ‘Full-Exposure” to an Orthodoxy Divine Liturgy Worship.

If so — it’s not at all surprising this brief and weak exposure

might drive any Protestant away (partly the point of Robert’s

call for an all-English Liturgy). Some things take time and the

Orthodox have no zeal (maybe even too little) to rush anyone

to embrace Orthodoxy before the time is right. All this is set

in contrast to just reading books and “talking online” to others

about Orthodoxy.

Nicodemus

Outlaw, (I feel like a character in Tombstone when I address you. The phrase “I’m your huckleberry” keeps popping into my head.)

I agree that a struggling ethnic parish that serves mostly in Greek would be a very difficult door through which to enter, or even discover, the Church. Alas, sometimes the clay is so thick it’s hard to tap a vein and find blood. I snuck over to your blog and went through your papers while you weren’t looking. You are clearly a well read and knowledgable theologian. In terms of academic theology you seem to have your ducks in a row at least in terms of cogency and consistency. As a continental reformed Christian I wonder what it is, other than a natural contrary streak, that interests in you in the worshipping life of the Orthodox Church rather than just in borrowing some of its theology which you have done? What are you looking for that you haven’t yet found? I look forward to your reply.

Greetings,

Well, the short answer is: I sympathetically pursued EOdox church for almost five years. While I appreciate much of it, there were issues that I couldn’t reconcile (which I’ve listed on my blog and have no intent to further derail the thread here). Ergo, I stayed Reformed.

I am not a contrarian, as Nicodemus knows. I am actually very mild-mannered and soft-spoken.

I am/was interested in EO because I, per Perry Robinson’s suggestion, wanted to learn the doctrine of the Trinity. Simple as that.

Thanks Outlaw,

Forgive me if I offended you with the “contrary” suggestion. Some of your theological interests seemed to suggest a contrary streak. In any case I didn’t intend it as an insult. Thank you for being so forthcoming. I am interested to learn your objections to EO so I will peruse your blog a bit more and perhaps we can continue this conversation when I have a better appreciation of where you are coming from.

No offense taken. The internet is a terrible medium for inflecting “tone.” True, I deal with pointed issues and sometimes there is no nicer-sounding way to say some things.

I appreciate your comments here about the limitations of TULIP. I particularly appreciated your inclusion of the thoughts of the Church Fathers.

Just last month I read a blog that explained Calvinism as an interdependent system where each tenant depends upon all the others. If you undermine one, you undermine them all. It was an article which sought to convince those who say they are Calvinists but have problem with the doctrine of limited atonement. The gist of the article was “you can’t be a four point Calvinist.”

I think your point by point objections to each of the TULIP tenants was very good and quickly highlighted in a Biblical way the weaknesses of each one.

So that you know a little about me, I grew up a Protestant with some exposure to the Lutheran liturgy. When I came to Christ in an informed, life-changing way and went back to church the liturgy came alive for me. So I appreciate tradition and traditional forms of worship.

I agree with Luther, however, that many unhealthy traditions were allowed to creep into the church over the ages, especially during the age when most were ignorant of the content of Scripture.

It’s no surprise that the Reformation happened when it did, on the heels of Scholasticism when professors were, for the first time in centuries, studying the Scriptures in their original languages.

Since you brought it up I’ll give just a quick word about misogyny. Victoria Clark in her book “Why Angels Fall: A Journey Through Orthodox Europe from Byzantium to Kosovo” documents that misogyny is alive and well in Orthodox circles. Her observations are unbiased but she asks some good questions just the same.

Welcome to the OrthodoxBridge! I’m glad you found my posting on TULIP helpful.

Actually, it was someone else who brought up the issue of misogyny. Your reference to Victoria Clark’s book sounds interesting.

Robert

Victoria Clark’s book is one of the worst I have ever read. She is almost gleeful that Orthodox Serbia is bombed. She is a liberal Romanist who denies (and ridicules) the deity of Christ (cf, specifically the part in the book where she has a discussion with a Serbian priest).

The chapter on the Old Believers, though, was kind of interesting. She basically identifies “fascist” with “most evil person imaginable” and labels anyone to the right of her as a “fascist.”

Robert,

As a former Calvinist I appreciate your treatment of TULIP. I think your references to the Sixth Council are very appropriate, and I myself have wrestled with the question of whether Calvinism’s anthropology is consistent with that of the Sixth Council. I appreciate the comments by others on this point, both pro and con. It’s not immediately clear. But it does seem that, to be consistent, Calvinism must assert *somewhere* that the divine will “superintended” (for lack of better terms) or somehow predestined the human will to be fully submissive to it. Thus it would seem that the two wills in Christ are not truly free relative to one another. This point does certainly warrant further investigation. In general I was never able to find much interaction with the Sixth Council among Reformed, either at my former church (“Oh, was that the one about the icons?”) or among otherwise well informed people on forums and the like. Those who did address it typically made a (what seemed to me to be rather contrived) differentiation between human will enslaved to sin, and human will not enslaved to sin. Something along the lines of “Only once the elect have been regenerated does the analogy to the Sixth Council become relevant to them” etc.

I think it’s also appropriate to point out that in general, most Protestant traditions present “synergy” as something of a zero-sum game. Some reformed authors have explained rather simplistically (in books addressing a general audience) Pelagianism = God 0%, Man 100%; Semipelagianism = God 99%, Man 1%; Calvinism = God 100%, Man 0%. And Arminians (one thinks of Billy Graham) will say such things as “God will do 99% for you, but you still have to do the 1%. You’re paralyzed in sickness, and God will go all the way to putting the medicine into your mouth, but you have to come through with that 1% effort and swallow it.” I paraphrase. But really, in Orthodox understanding, if one were to try to express it using cheesy formulas, it would be God 100%, Man 100%. Because it is God working in, and through, man. Similar to the relationship of Scripture and the Church. One doesn’t undermine the other…Scripture is God speaking in and through the Church. So when one places his/her faith in Christ, they are not just having faith in Christ, but they are having the faith OF Christ working in them.

So the entire paradigm in which synergy is understood differs between Calvinism and Orthodoxy, the former seeing it as being complementary and additive, the latter seeing it as being holistic and a participation in the life and work of the Trinity.

Just some thoughts…my two cents, and worth every penny!

Welcome to the OrthodoxBridge!

Thank you for sharing your insights with us. As I read your comments I thought of Jesus and the paralyzed man in John 5 in which Jesus asked the man: Do you want to get well? (John 5:6) He has the power to heal but we have to want to be healed.

Robert

Bill T,

Good insights. We discussed this a little in the comments in other places as well, though I forget exactly where….except for this one:

https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/orthodoxbridge/patristics-for-baptists/

The Reformed always seem to begin with fallen man as home base for their anthropology instead of the man Christ Jesus.

It is important to note that both Luther and Calvin based their doctrine of total depravity on the writings of Augustine of Hippo. Unfortunately, St. Augustine read an incorrect translation of Romans 5:12. “Therefore as sin came into the world through one man and death through sin, and so death spread to all men because all men sinned…” However, in the Latin version of the text instead of “because all men sinned.” it reads “in whom all sinned.” From this Augustine developed the doctrine of original sin with the doctrine of inherited guilt and with it total depravity. Because the Orthodox read the text in the original Greek, we did not develop Augustine’s doctrine of original sin that played a very important role in Calvin’s thought. If you look at the index of most editions of the Institutes, you will find that Calvin constantly invokes Augustine.

Fr, John W. Morris

Thank you. I would like to add, synergy is, scientifically speaking, the behaviour of whole systems unpredicted by behavior of the parts. The entire cosmos is synergistic. This is a mystery. The Church in its process of deificiation is synergistic not only with each other but with the Trinity.

And don’t forget, next you’ll need to interact with B.A.C.O.N. 🙂

http://www.choosinghats.com/2012/06/bacon-its-new-tulip/

Hey, hey…and BACON tastes better than TULIP!

When God assumes human nature, human nature is automatically restored to its original health (at least within the particular person–or Person–in whom God dwells fully), no? The healthy human will, made in the image of God, will then naturally, i.e., according to its original created design, align itself with that of God, no? Though, in the face of temptation and corruption in the fallen world, this would not be without struggle and painful consequences (as we see most clearly in the Garden of Gethsemene). At least, that is how it seems to me.

Many comments here (like Karen’s above) bring up a philosophical presupposition that seems to be key to our understanding, however, it’s convoluted and there are many differing historical interpretations of its role in Christian thought and philosophy, particularly as related to the Reformation. That matter would be the understanding of “human nature,” and whether such a thing actually has existance, and as such can be redeemed.

As I understand it (minimally, and poorly, from 2nd, 3rd, and 127th hand sources), early Christianity worked within what could have been loosely called a platonic framework, in which something like “Human Nature” could be considered an “ideal” or “form” that serves as a prototype for all individual humans, who (in some manner) participate in that reality. For Platonists I think this would have existed abstractly, in some ideal realm of forms “out there, somewhere.” For Christians, it would exist “in the mind of God.” I know this was a point of difference with thought shaped by Aristotle, whose thought played a pretty key role in western scholastic thought, but I readily admit to not quite grasping the difference in how “Human Nature” would be understood.

But later, “nominalism” came to deny that ideals or natures existed at all…there is no “Humanity” but only individual humans that we abstractly lable “Humans” based on observations of shared characteristics. Now, many non Protestants seem to believe that Luther and Calvin were thoroughly influenced by nominalism, while not actually labeling them “nominalists.” But surely, Protestant theology of salvation seems to pay little attention to “Human Nature” as a thing in itself, but rather emphasizes only individual humans. Election is God’s choice of which individual humans will be saved, and which will be damned. One Presbyterian pastor did tell me flatly “There’s no human nature that can be saved, there are only humans that can be saved.”

So I pose to those who are far better educated than I am…is this difference a major differentiator between the two points of view? If so then it seems irreconcilable. From an Orthodox POV, Christ united himself to Human Nature and redeemed Human Nature, in which we then participate through faith and baptism, growing in our union over time through repentance and faith working in love…what is “saved” is the Body of Christ, and individual humans are saved in and through union with that Body. From a Protestant POV, as it was always explained to me, what is “saved” are individual humans, starting with election and ending with glorification, and the Body of Christ–the Church–consists of the collection of those saved individuals.

Kind of.

Per the “nominalism,” Richard Muller has decisively buried the idea that Prots were nominalists en tot (cf. Reformed and Post-Reformation Dogmatics, volume 1).

The problem with discussing human nature as an ideal vs. particular is that both sides, if viewed consistently, lead to problems. A lot of follwers of Maximus like to say that human nature (vis-a-vis what Christ assumed) participated in cross or resurrection or whatever (perry made the argument somewhere on his blog regarding John 6). The problem is, as adherents of St Cyril know, natures do not *do* anything, much less participate).

There are other philosophical problems with the hard realism view that many Orthodox hold to; I might list them later on my blog.

(Of course, I don’t minimize some problems Prots have).

The Reformed do not permit the human to share the interpenetration of the divine energies, even in Christ. This amounts to an exchange of names only. Deification is more than making human flesh stop decaying and get back to what Adam was. Christ raises human nature far above the capabilities of prelapsarian Adam by deification and yet does this without change (hence our views of the eucharist and the Mother of God). His flesh becomes “life-giving”. Human nature DOES exist separate from a human person, but not apart from “some person”. Christ is a divine person and he assumed the substance of humanity from the Theotokos, our very essence, not an ideal or idea, and it subsisted in God the Word. Christ is acting on human nature and in fact all creation in his assumption of the created. His actions are cosmic, not just personal and when the Reformed have Christ only consubstantial with the elect rather than tasting death for every man, they are confusing person and nature.

Christ’s human nature did not “do” anything on it’s own, but freely followed and operated without resistance, supplying to the one personal agent in which it subsisted (God the Word) that which was proper to that nature. Nature participates freely and fully in the divine apart from a human person. God is really joined to man in Christ. This is why it is ontological and not merely forensic. It does not require a human person for human nature to participate in divinity.

When applied personally this results in human persons through gracious adoption sharing in the communion of the persons of the Trinity and not acting against nature and against God.

When Christ assumed this universal human nature (and thus positing an identity between our nature and his), is the identity between the two a generic identity or a numeric identity?

Outlaw, Bayou, Cyril,

I left a bit of a snarky comment that I think Robert is holding in moderation, so I’ll play a bit nicer…..not so “contrarian”.

Please clarify your last question (which is hopefully your own).

i’ll clarify later today. hurricane isaac about to wipe out power…

I think we weathered the worst of the Hurricane. I’ll keep the answer short

numeric identity: this is akin to the Romanist doctrine of absolute simplicity–reducing everything to the One.

Generic identity: similar to what Nyssa said in “Not three Gods.”

Generic better than numeric, but still problematic when applied en toto to Christ’s human nature

Bayou,

I see that this came from Drake’s post on his blog the other day.

My reference of information is thin on this, so just thinking outloud.

It may be elements of both. Though the Trinity shares the divine nature, the Persons use the natural faculties to do individual activities. There must be one numeric will and energy, but yet the only the Father wills the begetting of the Son and the procession of the Spirit. The Son does not cause his own begetting, yet he shares the very will of the Person who begat.

For us, Christ shares our nature and unites it to God in himself affecting the whole cosmos. Yet when Christ employed his human will, he did not make every human person will the exact same thing. So it seems there is a generic identity but with certain singular and numeric results. I may have just destroyed the Godhead with evil surmisings 🙂

Canadian,

We’re in deep waters here. Let’s be prudent and heed the teachings of the Church. As far as your last remark about a “generic identity” I believe you are thinking about Christ as the Second Adam. When we are baptized into Christ we join ourselves to Christ becoming part of the new creation. It is a personal union with Jesus Christ, the second Person of the Trinity. We need to choose to be in communion with Christ and his Body, the Church. No longer are we individuals per se but persons in communion with the Godhead (I’m paraphrasing Metropolitan John Zizioulas’ “Being as Communion”).

Robert

It was interesting to read this article as a Calvinist as I randomly found this article by searching for something completely else.

My understanding that this criticism is mostly about the debate on free will. Here I have some arguments — mentioning that the Canons of Dort is not fully accepted by everyone even inside the Reformed Church, some reformed people — like myself — reject Limited Atonement for example…

1. the usage and meaning of “free will” term by John Calvin and Augustine is not necessarily the same as the usage by the Church Fathers: at Augustine and Calvin it is solely about the will of obeying or not obeying God. Their conclusion is mainly that the sin impacted the free will that it cannot perfectly follow God’s will and please him.

The Church Fathers are more talking about the responsibility of each person due to his deeds and will — which Calvin himself confirmed when warned against making conclusions of combining free will and predestination, leading to misunderstanding both doctrines. By Calvin, predestination cannot be an argument against free will — unless it is a big misinterpretation of any or both of the two!

2. for me itself you draw stronger conclusions of the quotes than they actually want to say. I could not read anywhere that there is no spiritual hunger in those who are not elected. However, such a spiritual hunger is so imperfect that without the help of the Holy Spirit it will not save anyone itself. My understanding is that there was no such claim that there is no spritual hunger at all and it is merely a false interpretation of it.

3. the logical conclusion of double predestrination implicitly relies on linear time. Unfortunately computer science is much younger than the debate on predestination and in the 16th century branching time temporal logics were not known. My personal understanding that almost everyone was thinking in linear time at that time implicitly, however I reject God’s foreknowledge as linear time. In that case, double predestination is not a logical consequence any more.

4. For me the implicit assumption on linear time in the 16th century explains why was it important for Calvin that predestination and free will cannot be used as an argument against each other — most likely he felt that there is a limitation in the logical framework around, however he was most probably not aware where the limitation comes from…

Jasper,

Welcome to the OrthodoxBridge! Your comment about linear time is interesting. I haven’t heard that line of reasoning before.

Robert

Hello Robert,

I hadn’t had either. The whole idea of linear time vs branching time came to me on a formal semantics seminary at the university — I am a computer scientist. The interesting thing that non-determinism usually has more expression power than determinism (you can do everything in a non-deterministic system what a deterministic could do, but not vice versa). And the really interesting questions come up with non-determinism.

After that I had read a little about the discussions on predestination and free will… and most of those issues are there due to everyone is implicitly relying on linear time.

I started to read the post, but when I found you had Total Depravity wrong decided I don’t have the time (I am under a deadline). I will return to read more. Your error concerns the Scot Confession – defaced does not equal eradication. You reach too far to characterize the Reformed position.

Chris,

Thank you for visiting the OrthodoxBridge! When you have the time, please feel free to read through the entire article and discuss it. I sought to base my findings on TULIP upon evidence, not personal preference. That is why I made numerous citations from key Reformed sources in my article. I trust you will have an open mind to the evidence I presented. I intended the OrthodoxBridge to be a place where frank and charitable dialogue can take place between the Reformed and Orthodox traditions. Hoping to hear from you soon.

Robert

Thank you very much for your web-site!

There is a very old debate regarding divine culpability to evil, in a world of Universal Divine Determinism, where God meticulously controls every neurological impulse a human has. The Determinist appears to appeal to secondary causes to remove culpability from God. And seems to rely upon the notion that man operating as an intermediate cause does so as a “self-powered” entity. The in-determinist, such as William Lane Craig, disagrees, and states: “These intermediate or secondary causes (i.e. humans under divine control) are not agents themselves but mere instrumental causes, for they have NO POWER TO INITIATE ACTION.

Craig’s assertion seems hard for me to comprehend. I wonder if he is speaking in strict terms of causation, rather than in terms of human faculty. Why is “Self-powered” action so necessary to remove culpability from God? Can’t a robot with the sentient abilities of man, be understood as performing “self-powered” action?

I get the impression, what is behind much of this, is a voluntaristic man, obsessed with creating God in his image. Who then has to become an expert sophist, in order, to draw off disciples after himself.

Your help appreciated!

Thank you for visiting the OrthodoxBridge!

The topic of determinism is a complex one. It is always important to take into account the context in which a philosopher or theologian makes a statement. It appears that the quote you provided came from William Lane Craig’s blog article “Molinism vs. Calvinism.” This might help you better understand that sentence. If not, the best thing would be to contact Prof. Lane directly either at ReasonableFaith.org or at the Talbot School of Theology.

As to what might be the motivation behind the Reformed tradition’s determinism, I prefer not to speculate. I am more concerned with whether the Reformed understanding of predestination is consistent with the historic Christian Faith as taught by the early Church Fathers. This is open to public scrutiny and assessment.

God’s blessing be with you.

Robert

Thank you Robert!

I appreciate much!

I’ll keep on digging on this question.

In the mean time, I again, I enjoy your site.

br.d :-]

There is a sense in which the “P” in the TULIP is a self-contradiction.