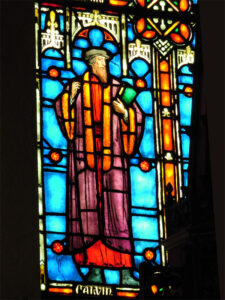

The Tipsy Teetotaler in a recent blog posting “Calvinist Concessions galore” featured Fuller Seminary professor William Dyrness‘ comments about the relation of arts to Reformed theology. One striking feature of Reformed Christianity is its puritanical austerity, especially with respect to the visual arts. That is why stained glass images like the one featured here are so striking. (Actually, it’s in the Lutheran Church of the Reformation in Washington D.C.) So rarely are visual arts found in Reformed churches.

Dyrness has done quite a bit of thinking and reflecting on creativity and aesthetics. This makes him quite unusual among Reformed theologians. In a recent interview on Mars Hill Audio Journal Dyrness makes a number of observations about certain problem areas in Reformed theology:

- The tendency to underplay the Incarnation;

- Not valuing the arts or visual imagery;

- The opinion that churches are not sacred spaces where one can go to pray outside of the Sunday worship; and

- Not appreciating the importance of contemplation. Reformed Christianity wants a “To Do List” instead of a vision of God.

These are pretty strong indictments coming from a Presbyterian minister teaching at a major Evangelical seminary. While Reformed Christians have engaged in the arts, these endeavors seem to be relegated to outside the church. Thus, for most part Reformed churches and services are marked by a stark austerity that frames the preaching of Scripture.

Dyrness has attempted to address this issue through a number of books:

Visual Faith: Art, Theology and Worship in Dialogue (Engaging Culture) (2001)

Poetic Theology: God and the Poetics of Everyday Life (2011)

Another way Reformed Christians can remedy the absence of the arts is through the exploration of the way Eastern Orthodoxy has incorporated the arts into the Liturgy. A visit to an Orthodox Liturgy will forever change one’s understanding of what worship is. Come and see!

Note: The beautiful stained glass image of John Calvin was copied from from Stock Photo Showcase.

In the neo-Calvinist (Dutch) tradition, there has been great reflection on art and aesthetics, especially by Dr. Calvin Seerveld, emeritus at the Institutes for Christian Studies in Toronto. The Dutch tradition, in general, has a much lighter grip on the “puritanical” side of Calvinism — the influence of Abraham Kuyper (who, some maintain, was heavily influenced by the Catholic mysticism of Baader) is strong here, especially as he claims that all of life (including the visual arts) belongs to and should glorify/witness to Christ.

So, while the Scottish branch of the Reformed tradition *tends* to be artless (although my very Scottish church has lots of stained glass, including a rose window, plus intentional architecture — the church looks like an ark on the inside), the Dutch are steadily leading a resurgence.

Just my two cents.

I was thinking the same thing Russ. The Continental Reformers were (& still are) a good bit friendlier to the visual Arts than were/are the English and Scott Puritans –also in their Churches as are Anglicans. One wonders IF there is a noticable difference in Christology between them?

Tilting at windmills as usual. This old stereotype is not only historically inaccurate, it’s tiresome to see yet one more post dealing with something other than the real thing.

A Christian tradition steeped in age-old stilted two-dimensional art turned idolatry really shouldn’t feel too confident about criticizing the supposed lack of arts and creativity in the Reformed tradition.

Kevin,

While it is certainly true that Reformed people have had huge artistic impacts–particular Dutch Reformed in the visual arts, and English in literature (Shakespeare, Spenser, Milton, Lewis etc.); and while it is true that Scott could (through Rob Roy) say that the Reformed Churches are the most beautiful in Christendom because of the singing; it is nevertheless true that most Reformed art is secular–even in music the Reformed lag greatly behind the Lutherans, though there are excellent Reformed composers like Handel and Justin Morgan. Nevertheless, I do not believe that is the focus of the post, but the internal critique from Dyrness, which seems spot on, at least regarding the modern Reformed church. (Though, of course there are exceptions.) If two Reformed pastors can tell me that it is heretical to believe that Mary is literally theotokos–thus condemning the Fifth Ecumenical Council as heretical, and claiming the position anathematized by that council is the orthodox one–it is fair to say the Reformed down-play the Incarnation. If L’Abri is any indication of what the Reformed world is like, then the Reformed need a greater emphasis on prayer, for for all their strengths, they aren’t a place of prayer, but of learning.

Matthew,

All this familiarity with the Reformed and you seem to forget that there is nothing that escapes the Lordship of Christ. You are welcome to use distinctions such as “secular”, but the Reformed do not see it as such. Nevertheless, the claim that Reformed Christianity (which is the term used above, not modern Reformed Christians–perhaps at some point we can ask the blog authors here to be more exacting in their language) downplays the arts is not true in the slightest. American Puritanism and some of her descendants may have had a less than appropriate appreciation of the arts but even here we must not forget the fabulous poetry and musical culture of the early American years. And, Puritanism usually gets a bad wrap early on by many with an axe to grind. We can’t forget, however, that Puritanism is only half the story as the institutional church in England carried on its Reformed identity still building cathedrals and contributing in magnificent ways to the arts as she went along.

I would be surprised however to see the good professor happy about his work being used to unduly compare Reformed Christianity to other expressions in order to see partisan movement from one communion to another. At the very least we all have to admit that modern Reformed communions directly related to Puritanism really only reflect a small part of the wider Reformed traditions in America and in Europe.

Some Reformed pastors are undoubtedly ill-educated but then so are the Roman priests who encourage folk religion and a worship of the saints that goes well beyond any finely tuned North American Catholic distinctions between worship to God and the intercession of the saints. So, where parts of one group in this era may tend to excess it would be no exaggeration that equal problems exist in all communions on a variety of issues.

I don’t have any problem with “theotokos” technically speaking and likely most Reformed pastors wouldn’t either except that certain communions have made all too much of Mary’s identity and work as well as her supposed intercession. So, there is some good reason you will find hesitation to admit to the orthodoxy of a loaded term when for most Roman Catholics it means so much more than the original “Godbearer” or “Mother of God” than the councils originally proposed. The original Reformers had little problem with the term of course and saw it as it was intended at the council, but five hundred years have gone by with reactionary voices and extremes running on both sides against any sort of moderate view you might like to have the Reformed take.

But again, to the subject of this post, it really is ironic that we find such a knock against Reformed Christianity by a tradition that is not overly creative or distinctive except within certain very predefined boundaries not at all characteristic of a wider catholic conception of art and its use. I can appreciate the aesthetic quality of the art and music of Orthodoxy over the centuries, but there is nothing in that tradition that makes its voice superior when we come to the subject.

As for whether the Reformed could pray more, perhaps we could. But, so then the whole world–we all fall short on many counts. I wouldn’t mind keeping churches open as a place of prayer but we also need to remain a bit wary of ecclesiocentrism where life revolves around the church instead of more properly around God’s kingdom.

“A Christian tradition steeped in age-old stilted two-dimensional art turned idolatry really shouldn’t feel too confident about criticizing the supposed lack of arts and creativity in the Reformed tradition.”

Ignorant and insulting to boot . . . as usual. Arrogance is insufferable in whomever displays it, but it is especially unbecoming in a Christian.

“All this familiarity with the Reformed and you seem to forget that there is nothing that escapes the Lordship of Christ. . . .”

Yes, that old wonderful catch phrase, nothing escapes the “Lordship of Christ,” except it would seem that for the Kevins of this world, liturgically that never becomes much more than abstract theory as demonstrated in Reformed liturgy, which is where we ought to see the symbolic outworking of the entirety of the faith’s implications. I thank God that I never have to go back to a corporate “worship” that happens only conceptually from the neck up, and too often primarily in fantasy. Did Christ redeem only our capacity for conceptualization and verbalization, or did He sanctify all aspects of our embodied humanity? Why can this not also be reflected in Christian liturgy?

Karen,

It is not ignorant or insulting to properly represent the Reformed view of icons in the main as it pertains to this issue. You may not agree with what I’ve said, but that doesn’t make it a display of arrogance. I would appreciate it if you would avoid reading intentions into my comments that are not there.

As far as the liturgy is concerned, I don’t believe your comments are particularly accurate of even the worst of Reformed liturgy and services today or those of yesteryear. And, even if there are Reformed churches that trend toward what you say–even they would not agree with your description of their services as you have put it. The intention of the Reformers in restoring the cup to the laity and making sure the service was in an understandable language spoke to the fact that they very much considered liturgy as something more than an exercise of the mind. Calvin’s Strasbourg Liturgy quite clearly shows that the Reformed very much considered worship to be an experience of and response to God in both word and deed. One of the clearest signals that such is the case is the congregational singing that the Reformers implemented as soon as they could break free from the shackles of Rome.

“There is nothing incarnational about the fact that often so much incense is used at a midnight Christmas service that some parishioners have to go outside and throw up on the lawn in order to be able to engage again in what’s going on.”

Oh, please . . . ! (As if this is what we Orthodox are claiming).

“The intention of the Reformers in restoring the cup to the laity and making sure the service was in an understandable language spoke to the fact that they very much considered liturgy as something more than an exercise of the mind. Calvin’s Strasbourg Liturgy quite clearly shows that the Reformed very much considered worship to be an experience of and response to God in both word and deed. One of the clearest signals that such is the case is the congregational singing that the Reformers implemented as soon as they could break free from the shackles of Rome.”

Some good points there, and I agree the Reformers did some good things and had many honorable intentions. But here’s a question of overall perspective that I’d like to ask. Don’t you think that a whole theological movement that began in *reaction* to the errors of another theological movement (Roman Catholicism) that itself was a departure from an earlier Christian tradition (I submit, recognizably more Orthodox), is at a disadvantage from the get-go (in terms of being a solid foundation on which to build a Christian theology and experience in its *fullness/wholeness*) from that which built and continued to build on the original and full apostolic foundation (as reflected, for example, in its liturgical development from the very beginning, and its adherence to the only universally accepted orthodox Christian Creed in dogma–and it’s overall liturgical and dogmatic stability)–whatever its historic lapses or excesses in actual practice?

Karen,

No. I have to disagree with the assumptions built into your question and therefore can’t provide you with the answer you would like to hear (you might take a look at complex questions to see why this sort of question isn’t helpful).

In truth, the historical reality is a little more complicated than you suppose. For one thing, the Reformation did not begin merely as a reaction to Rome but it was instead first an *embrace* of the Gospel. And, there was an attempt to reform within the Church however much Rome resisted such change. So, to say that the Reformation began merely in reaction to errors is not exactly the whole truth.

Furthermore, the assumption that Eastern Orthodoxy is somehow an unchanged apostolic ideal is equally problematic and something which you’d have to establish before a legitimate answer to your question could be given. History speaks against such a claim (though undoubtedly you and others would disagree). The truth is that the closed ethnic nature of much of Orthodoxy is just as stifling from the standpoint of catholicity as any sort of reactionary model you would like to lay on the backs of the Reformed.

That said, I do lament the divisions we have but the solution to returning to “one holy catholic and apostolic church” visibly will not be found in picking one communion over the other. Instead, the hard differences between us must be resolved or we are merely just playing at these things.

Certainly what we proclaim in liturgy is not always well followed up and reflected in the whole of life as it should be. (It is after all a very high standard we proclaim.) On the other hand, where there is a systematic disconnect liturgically (and by implication theologically) between what is understood and verbally proclaimed as “the faith” and the whole of our embodied and relational existence, you can guarantee that there is going to be a disconnect relationally and spiritually when we leave the doors of the church and go out into our everyday life as well. The bottom line of what I’m trying to say is that in my experience if “everything is sacred” in the sense that so much of Protestantism wants to proclaim (i.e., by intentionally *not* symbolically indicating that reality physically and liturgically in the way more Catholic and Orthodox traditions do, through such ritual actions as the blessing of water and oil and anointing people and objects with these blessed elements, through visual art, through ritual actions of prostration, bowing and kissing, etc.), in the rest of life, for all practical purposes, the actual “sacredness” of things gets seriously underplayed in our awareness, if not outright eliminated, as well. The rituals of a more embodied kind of Christian liturgy serve to instruct us as to what the sanctity of the Creation really means and what our attitude ought to be toward, God, the heroes of the faith, our fellow believers, and ultimately toward all other human beings.

I think it would do us well to remember that our experiences are hardly universal and make a very bad way to reason about the legitimacy or lack thereof concerning the way other Christians go about exercising their faith.

No, you don’t get off the hook that easily, Kevin! The only way any Christian can speak with full spiritual integrity is from a level that also incorporates personal experience, and I’m sick to death of that being used as an excuse and red herring to dismiss what truth is in that experience! There is indeed something very universal in all our *human* experience (and which I believe is implicated in my particular experience) which we ignore to our own loss. The essential wholeness of how we relate to the universal essential needs of our embodied humanity and the deep convictions in our heart and conscience that exist thanks to the Presence of the Holy Spirit deeply affect how we approach, conceptualize and live the faith, and I do believe my personal experience relates to that universal human experience and you could approach it from that perspective with spiritual profit to both of us if you chose to do so.

I’m not denying that our experience teaches us or that there is a universal connection between us in that regard. I’m denying that you have a rational basis on the part of your experience to indict entire traditions of Protestants and others simply because you’ve had bad experiences with their liturgies.

Kevin, let me clarify for you because I think you still misunderstand me because of my use of exaggeration. (BTW, I’d be glad to forego exaggeration as a rhetorical device on this blog in the future, if you would also, because, despite my recent, shall we say “more-heated” approach to communication, on a more serious note, my only real interest here is in seeing more accurate and deeper mutual understanding.)

So to clarify, I did *not* become Orthodox because I had “bad experiences in Protestant liturgies.” I had many very good experiences over five decades (and continue to have some good experiences, since I still attend my husband’s Evangelical church with him part time) in about as many different Protestant liturgies, and if you include liturgical experiences that combine many different Protestant liturgical/theological traditions, you could multiply that number). But when all is said and done, they all fell short of what I found I really needed to connect with God at the level that gave me hope for real and steady transformation into the image of Christ.

I wasn’t running away (intentionally) from something I recognized at the time as poor/incomplete liturgy. I was actually looking for, running toward, a more whole and coherent soteriology. That was the driving impetus for me. Getting the full Orthodox Liturgy along with that was the fringe benefit that came with the package! 🙂

I understand where you’re coming from but ultimately you’ve indicated that you’ve come to Orthodoxy based off a perceived need and your own experiences. That’s fine but it’s inherently subjective and not necessarily a reason for anyone else to convert.

Kevin, I entered my follow up comment before I saw you had responded to my first. I can agree to disagree with you on your first comment.

With regard to your second, *of course,* my description of Protestant and Reformed liturgy should only be understood in a relative, not an absolute sense, so please don’t let that fact distract you from the truth of my point. Comparative to my experience in Orthodox liturgy, I can say realistically (even though I worshipped in a Protestant tradition far more open to liturgical creativity and use of more visual aids, drama, etc., to communicate the faith) ultimately, too often this is what corporate worship for the body in the pew/audience boiled down to. I exaggerate to point out a particular error of tendency which I find embodied and reflected in all of Protestant liturgy on some level or other and which I regard as a loss (in differing areas and degrees) of the integrity and wholeness of the genuinely universal Christian tradition. Perhaps what I am trying to point out will be more clear when you read my follow up.

OK. Well, hopefully what is good for the goose is well, you know. Because, when I engage in hyperbole on a site like this I get called to the carpet.

It’s one thing to say this has been my experience and that’s fine. But, when you indict the whole of Protestant liturgy and practice on the basis of that experience you’re arguing beyond where reason would legitimately take you.

And, it is not only the Reformed communions that suffer from incarnational issues concerning liturgy. There is nothing incarnational about the fact that often so much incense is used at a midnight Christmas service that some parishioners have to go outside and throw up on the lawn in order to be able to engage again in what’s going on.

Kevin, I can’t hit “reply” to your two most recent posts, but I agree with a lot of what you have to say and especially in your second shorter comment. The “Orthodoxy” I would advocate doesn’t perfectly coincide with every aspect of the human Orthodox institutions as they presently exist on the ground (though, I believe, it is always fully contained in potential within them). There are, as I acknowledged in a previous comment, many “lapses and excesses” in historic practice in this sense. But it seems to me, a *full* embrace of Christian orthodoxy/Orthodoxy is also in many ways impossible apart from them. My goal at this blog is not conversion of anyone (I have no such grandiose expectations!). It is just to challenge notions I have discovered are patently untrue, and call out communication styles and attitudes I find uncharitable and unreasonable, and thus perhaps aid some in better mutual respect and understanding. (Undoubtedly, my desires far exceed my communication or reasoning skills.) In no way am I intending to advocate embrace of Orthodoxy in it’s *merely* human institutional reality on the ground (more like *in spite of* a lot of that!). And, in fact, my goal in posting here is not to “convert” anyone to Orthodoxy in this sense. I actually believe that would be quite dangerous and detrimental spiritually for many, because, again in my own experience, nowhere is the spiritual battle for the souls of Christians more intense than in the Orthodox institutional Church at this time in history. The only reason to become a member of an Orthodox parish is because you have come to believe that Orthodoxy in its liturgy and dogma is the fullness of the truth and that it is God’s will for you at that time and place. My only goal in posting here has been a (certainly flawed and incomplete) attempt to dislodge apparent “certainties,” that keep Christians in certain Protestant traditions from better understanding and respect of those in other Protestant traditions or in the Orthodox tradition in particular. It has also been to protest what I have perceived on the part of you and Tim in particular as a strong prejudice and predisposition to interpret the “other” tradition in the worst possible light, prompting in me somewhat of “an equal and opposite reaction.” Ironically, I suspect that this may in fact turn out to be because both of us are a lot closer in our actual convictions of the outworkings of a fully orthodox/Orthodox Christian faith and its corporate expression than many other Christians in the wider Protestant world and certainly than in the nominally or merely ethnically “Orthodox” world.

(cont.) Where I must continue to disagree with you is with the inference you make in your second comment that the fact that I felt drawn by a need to Orthodoxy necessarily implies that this need was not also related to the existence within Orthodoxy of a better connection to “objective” spiritual reality, i.e., Christ as He has revealed Himself in Scripture and within His Church. There is a false dichotomy in this mindset between “subjective” experience and “objective” truth when it comes to the realm of the spiritual (where “truth,” by *Christian* definition, is more properly defined in terms of the relational and personal, i.e., Christ, than in terms of supposedly “objective” philosophical propositions, however “Scriptural” the wording and rationale). I have yet to meet anyone who came to Christ, who did not do so because they had some sort of profound and convincing subjective experience and/or sense of need. On the other hand, I have never seen propositional or rational argument alone, no matter how reasonable or persuasive, convince anyone to come to Christ (or, perhaps closer to our concerns here, which has enabled true heart change in the direction of the humble and compassionate mindset of Christ, for that matter). And often, such subjective experience of the truth of Christ and/or of His Self-expression within a certain tradition, has had to overrule much persuasive propositional argument and other internally logically coherent but opposed philosophies as well as adverse consequences and circumstances to do that. The reality is most of us who have become Orthodox have also had some very good subjective experiential reasons to *not* do so. I am no exception to this. So I conclude that aspect of your comment is also a red herring. The human being and psychologist within me is acutely aware that no human being embraces what he deems “truth” in a personal or subjective experiential vacuum, supposedly for the bare “objective” obviousness of the external “facts.”

To clarify my point, one of my sentences should read: “There is a false dichotomy in this mindset between “subjective” experience and “objective” truth when it comes to the realm of the spiritual (where “truth,” by *Christian* definition, is more properly defined in terms of the relational and personal, i.e., Christ, than in terms of supposedly “objective” philosophical propositions or historical analyses, however “Scriptural” the wording and rationale, or “undisputed” the historical facts invoked for support may be).

I’ll also add to this, one cannot simply dismiss the personal and experiential as not being germane to these kinds of discussions because everything that has happened in history or which is recorded in Scripture requires interpretation, which is always a function of the whole of our human experience.

Having said that, in sharing from my experience, let me emphasize I’m looking only for respect and fuller understanding, not followers, groupies or converts!

While I did not appreciate the tone Kevin made his original point, it is clearly true that Reformed Christians have much art, even much Church art. Protestant religious art tends to be not visual, but musical, and though the Reformed do not have the heritage of the Lutherans, the Reformed do have their own great musicians. Handel is the obvious one, and to some degree Tallis and Byrd (who, though Catholic wrote Anglican services), and a score of more minor English composers. If we wish to exclude the Anglicans, so that by “Reformed” we mean “in the Puritan tradition” there are great composers like Justin Morgan, and Sir Walter Scott claims in Rob Roy (or rather one of the characters claims, and makes a plausible case) that the Reformed services in Scotland are the most beautiful in all Europe.

That said, the Orthodox today do outshine the Protestants and Catholics in many areas. The question is whether that is an accident of history, or a theological truth. It’s commonplace to say Orthodox have the most beautiful service, and their service is beautiful. But if beauty is the only criterion, I’d take the Leipzig Thomaskirche from around 1630 over any orthodox church ever, even the Hagia Sophia.

What we are facing today is something of a reversal of six hundred years ago. At that time, both Constantinople and Moscow were occupied by infidels, and Orthodoxy seemed to be dying, and not vibrant; whereas the West was producing such masters as Dante, Boccacio, Giotto, Fra Angelico, Petrarch, Dufay, Josquin, Chaucer, and the like. Whereas now, the Western Churches are occupied (this time internally) by the infidels, whereas the Orthodox are relatively healthy.

Which is not to say that there are not significant theological differences between the two, and that the Orthodox may be in a significantly better position theologically. Only that culturally and artistically, the Western Church is by and large, at historically low ebb, and the Orthodox at the highest flow in the last six hundred years.

Matthew,

I do wonder if the advances of the Western Church and its corresponding civilization have now made Orthodoxy available where before it was clouded in some faraway unreachable land. Wouldn’t it be ironic to find out that this so-called surge in Orthodox circles is due to the technological prowess of a Western and largely Christian society? To me, northeastern progressives are merely the apostate versions of their Puritan forefathers and as such represent Christianity (though badly) as much as their fathers did. In other words, a la David Martin and others–once we dispense with the myth of secularism things get a lot clearer. I do agree that the Western Church has faced and is continuing to face decline at least in the Northern Hemisphere and among non-immigrant populations. But, could it be that part of the reason Orthodoxy is attractive to some is simply because it was a previously unavailable taboo?

Well said Matthew. Though, all traditions tend to overplay their hand and points of differences against others, it is noteworthy that the original criticism above came from a Protestant Seminary Professor. Does he have a point? And whether it arises from his thoughtful reflection, or from his experience, why must we choose…why not both? Expereince can be abused or underplayed — though it’s difficult to read much Scripture (especially the New Testament) without running head first into one of the Apostles or a convert “arguing” from their experience. And hopefully, Kevin does not intend to first neuter the place of experience…only to imply that exceptional “incense-to-vomiting experience” of whomever…should be universally applied!

So, are the points/criticisms Prof. Dyrness want to make against the Reformed:

■The tendency to underplay the Incarnation;

■Not valuing the arts or visual imagery;

■The opinion that churches are not sacred spaces where one can go to pray outside of the Sunday worship; and

■Not appreciating the importance of contemplation. Reformed Christianity wants a “To Do List” instead of a vision of God.

valid or not? And perhaps more importantly, are their Theological reasons for these tendencies? With some Anglican and Lutheran exceptions, they certainly seem broadly to be true. Rather than trash the criticism as trivial/irrelevant, it might be more profitable to engage them…and ask ourselves if the Incarnational “Why” really has an merit? Otherwise we might drift over to the notion that Truth and Material/Creational-Beauty really have little to do with each other.

I chuckled when I saw Dyrness’ name mentioned. RTS required his books read in seminary, though the prof who had required Dyrness has since been fired.

What’s funny is that everyone is getting angry and seeing this as an orthodox rant against Protestant ugliness, but that the argument itself was taken from a….PROTESTANT!!!!!!!!!!!!! lol!

Or Dyrness used to be Protestant. I think he still is. Anyway, outside of some liberal Protestant churches, they usually are ugly. My church has four ugly white walls with migraine-inducing lights. Yet, that simplicity is supposedly “beautiful.”