The “fall of the church” heresy is widely held among Protestants but not unique to Protestants. The “fall of the church” was something that early Christians had to contend with as well. Tertullian answered it in “The Prescription Against Heretics.”

The “fall of the church” refers to the belief that after the Apostles died the early Christians strayed from the original Apostles’ teachings and practices. This has been known as the great Apostasy, or the BOBO theory – the Blink Off/Blink On of the Holy Spirit’s activity in the life of the Church.

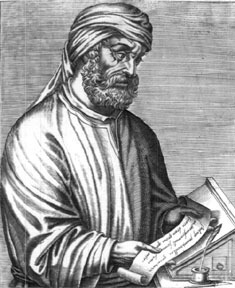

Tertullian (c. 160 – c. 225) lived in Carthage, a North African Roman province. He was a lawyer by training and one of the more influential Latin theologians in the early Church. While he did fall into error towards the end of his life and is not considered by many Orthodox a “church father,” his early writings can nevertheless be helpful to understanding early Christianity.

Prescription is one of the more important and highly regarded works of Tertullian for patristic studies. Quasten wrote in his Patrology:

De praesciptione haereticorum is by far the most finished, the most characteristic, and the most valuable of Tertullian’s writings. The main ideas of this treatise have won for it enduring timeliness and admiration. Although it can be assigned no definite date, it was quite obviously written when the author was still on the best of terms with the Catholic Church, probably around the year 200 A.D. (p. 272)

Defining Orthodoxy

The “fall of the church” was one of several arguments used by early heretics to draw people away from the Church. To understand these errors it is important to understand the way early Christians understood orthodoxy. In the early Church orthodoxy (right doctrine) was based on apostolicity. Apostolicity meant that a local church was able to trace its teachings back to the original Apostles via the traditioning process.

Tertullian wrote:

It remains, then, that we demonstrate whether this doctrine of ours, of which we have not given the rule, has its origin in the tradition of the apostles and whether all other doctrines do not ipso facto proceed from falsehood. (Prescription 21; italics in original; bold added).

. . . and after first bearing witness to the faith in Jesus Christ throughout Judaea, and founding churches (there), they next went forth into the world and preached the same doctrine of the same faith to the nations. They then in like manner founded churches in every city, from which all the other churches, one after another, derived the tradition of the faith, and the seeds of doctrine, and are every day deriving them, that they may become churches. Indeed, it is on this account only that they will be able to deem themselves apostolic, as being the offspring of apostolic churches. (Prescription 20.4-6; emphasis added)

Here we see that the Great Commission is basically the transmission of Holy Tradition. This may come as a surprise to many Evangelicals who assume that the Apostles went out to all the nations with a leather bound Bible under their arms. But it needs to be kept in mind that all that the Apostles had were Christ’s teachings and deeds carefully memorized and stored in their hearts. Similarly, when they planted churches the early converts had to learn by heart the Apostles’ teachings. It would not be until decades later that the Gospels and the Epistles be written down on paper; and even then it would not be until centuries later that a formal collection known as the “New Testament” came to be recognized by the early Church. The biblical canon came about as the early bishops individually and in councils carefully scrutinized which early writings were indeed divinely inspired and apostolic.

In Tertullian’s time there were churches planted by the Apostles and there were churches that learned the Gospel from the first churches; both could claim apostolicity in light of the fact that they shared the same Apostolic Faith. Tertullian wrote:

Therefore the churches, although they are so many and so great, comprise but the one primitive church, (founded) by the apostles, from which they all (spring). In this way all are primitive, and all are apostolic, whilst they are all proved to be one, in (unbroken) unity, by their peaceful communion, and title of brotherhood, and bond of hospitality, —privileges which no other rule directs than the one tradition of the selfsame mystery. (Prescription 20.7-8; emphasis added)

In Tertullian’s time Christianity did not have an elaborate set of institutions like seminaries, bookstores, bible camps, and TV stations. Basically, early Christianity consisted of the local church under the leadership of the bishop, the successor to the Apostles. For Tertullian one indicator of theological orthodoxy was being able to trace one’s bishop’s succession back to the original Apostles.

But if there be any (heresies) which are bold enough to plant themselves in the midst of the apostolic age, that they may thereby seem to have been handed down by the apostles, because they existed in the time of the apostles, we can say: Let them produce the original records of their churches; let them unfold the roll of their bishops, running down in due succession from the beginning in such a manner that [that first bishop of theirs ] bishop shall be able to show for his ordainer and predecessor some one of the apostles or of apostolic men,— a man, moreover, who continued steadfast with the apostles. (Prescription 32; emphasis added)

Just as significant is the importance Tertullian placed on the Eucharist as proof of orthodoxy: to be doctrinally orthodox was to be in communion with the apostolic churches. In the early church the claim was made that the teachings one heard at the weekly Eucharist were the same one as that taught by the original Twelve.

We hold communion with the apostolic churches because our doctrine is in no respect different from theirs. This is our witness to the truth. (Prescription 21)

In summary, Tertullian’s description of early orthodoxy consisted of: (1) the traditioning process, (2) the local bishop as successor to the Apostles, and (3) the Eucharist as the sign of doctrinal unity.

Holy Tradition or Sola Scriptura?

Tertullian advanced a number of arguments that would make a Protestant’s hair stand. In Prescription 19.1 he opens with: “Our appeal, therefore, must not be made to the Scriptures. . . .” Unlike Protestants who view Scriptures as a level playing field that anyone can read and anyone can interpret according to their conscience, Tertullian viewed Scripture as part of the sacred deposit entrusted to Church, recognized by the Church, and safeguarded for future generations by that same Church.

For wherever it shall be manifest that the true Christian rule and faith shall be, there will likewise be the true Scriptures and expositions thereof, and all the Christian traditions. (Prescription 19.3; italics in original)

There is no shred of evidence of Protestantism’s sola scriptura in Tertullian’s Prescription. What we find is the oral Tradition supplemented by written Tradition, and the two complementing the other.

Now, what that was which they preached—in other words, what it was which Christ revealed to them—can, as I must here likewise prescribe, properly be proved in no other way than by those very churches which the apostles founded in person by declaring the gospel to them directly themselves, both viva voce, as the phrase is, and subsequently by their epistles (Prescription 21.3; italics in original; bold added)

The early Christians never separated the two but saw the oral and the written forms of Tradition as integral to each other. Naturally, the oral form of the Apostolic teaching preceded the written form and continues to this day to inform the Church’s understanding of the New Testament text. In other words, early biblical exegesis was rooted in oral Tradition and did not arise from an independent objective reading of the Scripture text. It was a ecclesial activity, and not something carried out independently of the Church and its bishops.

Early Attacks on Orthodoxy

The early heretics used a variety of arguments designed to undermine the faith of the early Christians. The heresies are all aimed at attacking the notion of apostolicity. They make sense if orthodoxy is grounded in the traditioning process; but don’t make sense if early orthodoxy is based on sola scriptura.

Heresy # 1 – Christ had Other Apostles (Prescription 21)

Heresy #2 -– The Apostles Didn’t Know All There Was to Know (Prescription 22.2)

Heresy #3 – The Apostles Knew All There Was to Know But Chose to Hold Some Things Back (Prescription 22.2)

Heresy #4 – Peter’s Knowledge of the Gospel Inferior to Paul’s (Prescription 23 & 24)

Heresy #5 – Paul’s Knowledge of the Gospel Superior to Peter’s (Prescription 23 & 24)

Tertullian Refutes the “Fall of the Church” Heresy

Tertullian describes the “fall of the church” heresy:

. . .let us see whether, while the apostles proclaimed it perhaps, simply and fully, the churches, through their own fault, set it forth otherwise than the apostles had done. (Prescription 27.1)

The early heretics cited Paul’s letter to the Galatians in support of the fall of the church theory: “O foolish Galatians, who hath bewitched you?” and “Ye did run so well; who hath hindered you?” They also pointed to Paul’s admonishment to the Corinthians about their being carnal and suited only for milk, not meat. Tertullian points out that the heretics failed to take into account that the early churches likewise responded to Paul’s correction. In addition, Tertullian pointed to Christ’s promise of the Holy Spirit guiding the Church “into all truth” (John 14:26) as evidence against the fall theory.

Grant, then, that all have erred; that the apostle was mistaken in giving his testimony; that the Holy Ghost had no such respect to any one (church) as to lead it into truth, although sent with this view by Christ, and for this asked of the Father that He might be the teacher of truth; grant, also, that He, the Steward of God, the Vicar of Christ, neglected His office, permitting the churches for a time to understand differently, (and) to believe differently, what He Himself was preaching by the apostles,—is it likely that so many churches, and they so great, should have gone astray into one and the same faith? (Prescription 28.1; emphasis added)

In Chapter 28, Tertullian points out the implication of the fall of the church heresy. It means a widespread apostasy among the early Christians and that even Paul was mistaken in his witness to the Gospel. Furthermore, it means that John 14:26 was not fulfilled even though Christ promised that He would send the Holy Spirit to guide the Church. Furthermore, it implies that the third Person of the Trinity, the Holy Spirit, the “Vicar of Christ” failed to do his job and that Christ made a false promise!

Tertullian points out that if the “fall of the church” theory held true then the churches would have diverged significantly from the teachings of the Apostles and that in turn would have resulted in theological divergences among the churches. But theological divergences were not to be found among the churches but with the heretics.

Error of doctrine in the churches must necessarily have produced various issues. When, however, that which is deposited among many is found to be one and the same, it is not the result of error, but of tradition. Can anyone, then, be reckless enough to say that they were in error who handed on the tradition? (Prescription 28.2-4)

Where diversity of doctrine is found, there, then, must the corruption both of the Scriptures and the expositions thereof be regarded as existing. On those whose purpose it was to teach differently, lay the necessity of differently arranging the instruments of doctrine. (Prescription 38.1-2)

Tertullian notes that where error results in fragmentation, orthodoxy results in doctrinal uniformity (unity) among the early Christians. Doctrinal unity flows from fidelity to the traditioning process used by the Apostles in transmitting the Gospel.

Tertullian sketches out what the “fall of the church” would have looked like if it did in fact happen:

During the interval the gospel was wrongly preached; men wrongly believed; so many thousands were wrongly baptized; so many works of faith were wrongly wrought; so many miraculous gifts, so many spiritual endowments, were wrongly set in operation; so many priestly functions, so many ministries, were wrongly executed; and, to sum up the whole, so many martyrs wrongly received their crowns! (Prescription 29.3)

In other words (at least in Tertullian’s mind) it is unthinkable and ludicrous to suppose that all the good things done by the early Christians were in fact bad things. Also, Tertullian points out that if such a massive defection had occurred then one logical consequence would be doctrinal pluralism. To put it another way, it does not make sense that so many Christians would have gone wrong all in the same direction at the same time!

Tertullian Compared With Irenaeus of Lyons

Where Tertullian’s standing as a church father is in question, the same cannot be said of Irenaeus of Lyons who is considered to be the greatest theologian of the second century. Tertullian and Irenaeus were contemporaries having lived in the latter half of the second century.

While Tertullian’s apologetics strategy In Prescription Against Heretics may strike Protestants as somewhat odd, it bears strong resemblance to Irenaeus’ Against Heresies. A comparison between the two shows strong similarities in the way they understood early orthodoxy: (1) both assumed doctrinal orthodoxy to rest on Apostolic Tradition (Prescription 20.4-6; Against Heresies 3.1.1), (2) both understood Apostolic Tradition to exist first in oral then in written form (Prescription 21.3; Against Heresies 3.4.2), (3) both taught that orthodox churches were those who could trace their bishop’s succession back to the original Apostles (Prescription 32.1; Against Heresies 3.3.1), and (4) both asserted that a key sign of doctrinal orthodoxy is the unity of faith among Christians (Prescription 20.7-8; Against Heresies 1.10.1).

Tertullian taken together with Irenaeus gives us valuable insight into the theological method of the early Church. Their theological method bears a striking resemblance to the Orthodox Church but also striking disparity with the theological method(s) of Protestantism.

Conclusions

The “fall of the church” heresy was not unique to Protestants but something that the early Church had to contend with as well. Protestants have used the “fall” as a way of justifying their breaking away from the Church of Rome, and the early heretics used it as a way creating an opening so they could present their alternative gospel to their listeners.

Tertullian refuted the “fall of the church” theory on four grounds: (1) biblical – it implied the failure of the Holy Spirit to guide the Church “into all truth” which in turn implied the failure of Christ’s promise in John 14:26, (2) theological – it implied the denial of divine sovereignty, (3) sociological – if true the fall of the church would have resulted into doctrinal fragmentation which flies in the face of the doctrinal unity shared by early Christians, and (4) historical –there was no evidence of a massive defection among early Christians.

Tertullian’s refutation of the “fall of the church” heresy is instructive for Orthodox-Reformed dialogue. It sheds light on how orthodoxy was understood in the early Church. In early Christianity orthodoxy was premised on apostolic succession and fidelity to the traditioning process resulting from a continuing Pentecost via the Holy Spirit. Capital “O” Orthodoxy today claims this same basis for its claim to be the true Church founded by Christ and his Apostles.

Protestants have an understanding of apostolicity different from Tertullian’s. The Protestant principle of sola scriptura assumes that apostolicity resides in the apostolic authorship of the New Testament and that Scripture is sufficient in itself to guarantee right doctrine. With the exception of the Anglicans, the vast majority of Protestants reject apostolic succession as a marker of orthodoxy.

One of the biggest challenges that Tertullian’s Prescription poses to Protestantism is his claim that heresy results in doctrinal diversity. This is especially daunting in light of the multitude of Protestant denominations. There are some Protestants who might point out differences even among some of the Apostolic Fathers, as if this disproves Tertullian’s claim to unity. What do we say to this? Was Tertullian’s sense of broad unity among the early churches wrong? Was there, as these Protestants must establish, a doctrinal free-for-all among the early churches? No, the early Christians’ unity in the Pentecost promise of the Holy Spirit was real and Tertullian was right. What differences that existed were largely minor for the Church as a whole and did not disrupt the Eucharistic unity among the early Christians. If there was no “fall of the church” in early Christianity then Protestants will need to reconsider their insistence on the need for the reform of the Church. Orthodoxy claims that in light of the fact that it has faithfully kept the Apostolic Tradition Protestants need look no further for the primitive apostolic Church described by Tertullian.

Robert Arakaki

Source

Tertullian. 1980. “The Prescription Against the Heretics.” In The Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol. III, pp. 243-265. Reprinted 1980. Translators: Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson. Wm. B. Eerdmans Press: Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Irenaeus of Lyons. 1985. “Against Heresies.” In The Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol. I, pp. 315-567. Reprinted 1985. Translators: A. Cleveland Coxe. Wm. B. Eerdmans Press: Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Quasten, Johannes. 1986. Patrology. Volume II. The Ante-Nicene Literature After Irenaeus. Christian Classics, Inc.: Westminster, Maryland.

This is another excellent article, Robert.

Perhaps I might add that applying the Biblical injunction: “By their fruits ye shall know them” (Matt 7:20) underlines the way in which we should interpret doctrinal consistency – the truth of faith in Jesus Christ is one, not manifold. And this principle reinforces Tertullian’s contention that it is breaking away from the true faith through heretical teachings that results in doctrinal diversity, whereas faithfulness to the Apostolic deposit results in one and the same faith shared by all the churches. Error gives rise to a plurality of “gospels.”

Protestantism should logically fall by its own maxim of sola scriptura. “Beloved, when I gave all diligence to write unto you of the common salvation, it was needful for me to write unto you, and exhort you that ye should earnestly contend for the faith which was once delivered unto the saints.” (Jude 1:3)

From this verse alone one can deduce (i) the existence of a common salvation, which must consist in a commonality of means, since the Apostles were not divided as to the content of the Gospel, as even Protestants themselves argue; and (ii) that this Apostolic faith is one, and needs to be safeguarded from the encroachment of error.

The divergence of doctrine and practice within Protestantism looks a lot like bad fruit, then, if one gives full weight to just a couple of excerpts from Scripture.

As with most errors of Protestantism, it comes back to the egregious principle of sola scriptura. But, ultimately, sola scriptura is hoist by its own petard: no reading of scripture alone can support the diversity of doctrine and practice one finds in Protestantism. Rather, Protestantism resembles Israel in the days when there was no king, and every man did what seemed right in his own eyes.

Indeed, taking evidence from more recent findings in the post-humanist science of anthropology, oral transmission is now widely regarded to be of high fidelity to its sources. So much so, that recent developments in legal theory (something beloved by Protestants) have begun to admit the oral histories of Aboriginal peoples as valid evidence in court.

One can even legitimately argue that where matters of eternal life are concerned, the motivation to pass on truth, without error and without innovation, is stronger even than in the preservation of a societal group’s history and identity.

Western culture’s elevation of the written over the oral has little justification, scientifically or historically. Any contention that the Christian community quickly fell into serious error must, thus, have the burden of proof placed squarely in its court. And, of course, a case without evidentiary support is no case whatever…

Peter,

Welcome to the OrthodoxBridge! I appreciate your insights.

Robert

This is a good critique against wider Evangelicalism but it doesn’t touch the tradition represented by Hooker, Bucer, Vermigli et al.

On a side note, and while we are at it, what about where Tertullian urges his wife that when he passes away she should imitate the devil-rites and borrow celibacy (and non-remarriage) from them?

I only mention that because when i bring up Tertullian in these discussions people tell me that he was a heretic, so he doesn’t count.

Since the tradition (I’m glad you used that term, as every branch of Christianity has one, even when specifically denied by its adherents) of Hooker, Bucer, Vermigli et al is a reformational phenomenon, it doesn’t really have much to say about the contended corruption of the post-Apostolic period, or have I missed your intent?

And while Tertullian went off the doctrinal rails later in life, espousing the prophetic millennialism of the Montanists, for example, that does not serve to invalidate the sound reasoning of Prescription; any more than, say, Bart D Ehrman’s departure from Christianity invalidates his early work in textual criticism.

Hooker, Bucer, and Vermigli were clearly in the Thomist-realist tradition. The innovation was not as extreme as often made out to be.

Olef,

Hooker was an Anglican (I use to read him back in my Anglican days, and from time to time I will still read him) and they embrace Apostolic succession to a degree.

But what about Bucer, Vermigli? Why do you say it doesn’t touch them for? Can they trace their bishops back to the Apostles? Can they trace their teaching about the Eucharist, Baptism, and free will back to the Apostles? If not then it touches their tradition too!

You know, I heard it said somewhere that the Reformed protestant movement was started by Zwingli during the time of lent. And all because he didn’t want to fast from eating sausages! He used a Solo Scriptura approach for his justification. If this is true then it shows that the Reformed movement really didn’t care about early Christian tradition from the start, and that they have a tendency to go in the BOBO (Blink on Blink off) direction.

Regardless of whether they held to apostolic succession (and I can prove later that that sword cuts both ways), they did not see themselves as “trail-of-blood Baptists” but rather built off the best traditions of the church.

Their thesis, if I may oversimplify, was simply that some aspects of church “tradition” simply made pronouncing the gospel difficult and so that had to read Scripture in a way that they could. yes, I realize I am using “gospel” differently that you. That does not bother me. I know that should make me a bad, arrogant modern. So be it.

Jacob said:

” they did not see themselves as “trail-of-blood Baptists” but rather built off the best traditions of the church.”

Isn’t this the view Phillip Schaff advocated and the Mercersburg group in general? Also isn’t this somewhat subjective? For who gets to decide what is “the best”? Isn’t that a form of cafeteria Christianity? What authority did they have to even do such a thing?

This view also seems to be the view of the C.R.E.C. protestant group. We are getting many converts from that fellowship and so the idea that Reformed Protestantism represented the best traditions of the Christian religion didn’t stop any of them from converting. For like I said, we tend to get a lot of people from the C.R.E.C.

Well, Rome was equally in error on the issue of Lent/sausages at the time. Rome was compelling people (by force) to abstain from eating and/or selling sausages during Lent. That’s completely missing the point of Lent (and other fasts), which are supposed to be _private_ devotions that are undertaken voluntarily; note that Orthodox Christians don’t advertise the fact that they are fasting.

Zwingli, of course, swung the pendulum completely in the other direction. Whereas Rome had turned fasting into something imposed on people by force (legalism), Zwingli rejected its value completely (antinomianism), throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

Of course, Zwingli was the kind of guy who didn’t shy away from stirring up disagreements like this; indeed, he was a polemicist and a controversialist. Kind of like Galileo (who made things a lot worse for himself by writing a satire in which he called the Pope “Simplicio”. Galileo wasn’t targeted solely for denying geocentrism; he was also a bit of a jerk and his own behavior led to him being treated more harshly than he otherwise would have). The Church Fathers were exactly the opposite; for them church unity was of paramount importance, so they were often willing to “agree to disagree” to preserve unity.

Jacob,

Marrying once for clergy was common in that era. It is unknown if Tertullian was always a laymen or a clergy before he left the church for the montanists….etc. But when he did leave he advocated against the Church’s tradition about marriage and a number of other things and so you can’t use his Montanist stuff (his later works) against us. You would have to use his orthodox material (his earlier works).

Also, the idea that a clergy could only marry once was a common idea. The scripture said that a clergy could have only one wife, well, that era (the late 1s century, 2nd century, and 3rd century) took that literally. Meaning the clergy only married once. If the wife died then they stayed single/celibate. That was the common view and it predates Tertullian. Now with that said it’s known that Tertullian was more strict and so if anything he could have gone beyond the common view, but there is nothing wrong with the being married once view for clergy.

You like to discredit (a smear campaign) Tertullian, Saint Irenaeus and others by finding some flaw in their thinking on a different issue. No one said they were perfect, and you most certainly are far from perfect. Someone can do a smear campaign on you! You love conspiracy theories! So does this mean that we must ignore everything you say because of it? No! So it doesn’t matter if Irenaeus believed Jesus to be 50 years old if the issue at hand is something else. The same is true with Tertullian! Look, Robert compared Tertullian’s view with Saint Irenaeus’s view in regards to this issue and so that makes it not just Tertullian’s view but more of an early Christian gloss in general.

A gloss that the Reformed don’t fit in

JNorm,

I admire your feisty responses to Jacob. However, please don’t even hint of a smear campaign against anyone! Granted that you may find his remarks annoying and snide but keep the focus on the conversation, not the person. I want the OrthodoxBridge to be a place free of personal attacks. But thank you for standing up for early church fathers! They certainly deserve our respect! We should be quick to honor them and slow to cast aspersion against them.

Robert

I did smear Tertullian. I think his two tracts on Marriage are the worst piece of literature in human history. I didn’t smear Irenaeus. His ontology is blessedly free from the chain of being that we find in Damasius (Ps. Dionysius).

***but there is nothing wrong with the being married once view for clergy.***

It is if you bind someone’s conscience, and Tertullian wasn’t writing to the clergy, but to his wife.

***You love conspiracy theories!***

Evidence?

Is it known for certain that Tertullian actually left the church? I’ve read some sources arguing that he merely sympathized with the Montanists but remained part of the orthodox Church, at least nominally. He was never formally excommunicated as far as I know, and I don’t think he ever disowned the church, or cut off ties with them, at any point. If anything he was a fence-sitter. In that respect he could be considered similar to someone like Thomas Merton (who was a lifelong Roman Catholic but was widely known to also dabble in Zen and other far-eastern spirituality, which he thought Catholicism needed more of), or in an Orthodox context, someone like Franky Schaeffer (who converted to Orthodoxy back in the 90s and is still technically Orthodox, but he is also extremely liberal in his theological and social views and he hangs around with “progressive Christian” types).

Anastasios, in regards to Tertullian leaving the church I think I got that from saint Cyprian or was it saint Jerome? I picked it up from someone living a century or two after Tertullian.

Anastasios,

Whether Tertullian did participate in schism or not (as you suggest), his writings have been divided into “before” and “after” groupings. The same could conceivably be done to the contemporary authors that you name, without doing damage to their positive contributions. The division is simply a caveat for the benefit of readers.

Thank you Robert.

This is an important piece, since it is relatively early and clearly contravenes the notion, evidently popular in Reformed circles, that the promise of Christ sending the Holy Spirit in John 14:26 was not meant for the Church but rather just for the Apostles.

Okay, let’s pretend for the moment that the Protestants were really revolutionary Trail-of-Blood Baptists. Could we at least interact with the supreme apex of Protestant thought? Guys like Turretin, Richard Muller–those guys. Shucks, even Bradley Nassif said one has to read Richard Muller in order to understand Protestant thought. I just don’t see this board interacting with the best of Protestant thought.

I mean, I went through Gregory Palamas and Khaled Anatolios line-by-line, for example. If you have a better source, I am interested. I know the response: “You can’t know Orthodoxy by books, you have to experience it.” That may well be so, but that line also serves to stifle any real discussion or critique.

Jacob/Olaf,

This comment is full of red herrings. There’s no reason to bring up the Baptists. This posting is about Tertullian, his definition of early orthodoxy, and his refutation of “fall of the church” heresy. So I don’t see why you insist on our discussing Turretin and Muller. The focus here is on Tertullian, not two theologians that most people do not know about. Unless you stay on topic, I’m going to have to conclude that you are wasting people’s time with these diversions. I’m sure you have read a lot of books but there’s no need for you parade your ‘superior’ reading on the OrthodoxBridge. You’ll get more respect from others if you stay on topic.

Robert

I bring it up in light of several other issues:

You say Tertullian “refutes” Fall of the Church Heresy. Two problems:

“Refutes” means shows that a position isn’t truth-preserving, whereas Tertullian’s comment is best seen as a rebuttal. But that leads to the second point:

Presumably this is aimed at…whom? The Reformed? It can’t be that because I demonstrated that the magisterial Reformers and scholastics did not see the Church as “falling” or “apostasizing,” otherwise it would have been very bizarre for these guys to quote Church fathers, since on the presumed reading they viewed them as apostates.

On the other hand, if it isn’t aimed at the Reformed, then it seems to be aimed at low-church evangelicalism, hence my Baptist reference.

Olaf/Jacob,

I’m not sure what dictionary you are using but according to the Oxford dictionary “to refute” means “to prove (a statement or theory) to be wrong or false; disprove.” So my use of the word “refutation” is appropriate.

Can Tertullian’s Prescription be applied to the Reformed tradition? The answer is ‘yes.’ In a recent posting “Calvin and the ‘Fall of the Church'” I provided excerpts from Calvin’s writing that showed that he believed that the early Church “degenerated” and “declined” (Institutes 1.11.13) and fell into “deep darkness (Necessity of Reforming the Church). I noticed that in your comments for that posting you never once dealt with the specific evidence I provided from Calvin. No, Calvin never used the word “garbage” but he did use the word “deep darkness”! That’s a red herring tactic you’re using here! The fact that Calvin felt free to use individual church fathers doesn’t negate his assessment of the early church as demonstrated by his straightforward statements. It would help if you stayed on topic and not attempt to derail the discussion.

Robert

// Presumably this is aimed at…whom? The Reformed? It can’t be that because I demonstrated that the magisterial Reformers and scholastics did not see the Church as “falling” or “apostasizing,” otherwise it would have been very bizarre for these guys to quote Church fathers, since on the presumed reading they viewed them as apostates. //

You keep conflating “falling” with “apostasizing”: again another red herring. Robert defined “falling” as the belief that “after the Apostles died the early Christians strayed from the original Apostles’ teachings and practices.” Is this not precisely what you and all Reformed must argue necessarily for self-justification? Otherwise, how do you explain the writer of the Didache, St Clement of Rome, and St Ignatius of Antioch – all having lived during NT times – as advocating the Eucharist as a sacrifice and as Christ´s actual flesh and blood? Logically, if the Reformed are correct on this point, then it follows that the Didache and Sts Clement and Ignatius were aberrations in this respect! You seem to want to play games and dance around this inevitable conclusion: if the Reformed are correct, then the Church had to have “fallen” in certain respects from Apostolic teaching (not necessarily “apostasized” though).

And yes, the fact that the Deformers – err I mean Reformers – quoted some of the Fathers simply is evidence of their logical inconsistencies, poor scholarship, deliberate duplicity, and general lack of familiarity with Eastern Christendom. Such isn´t evidence that they didn´t believe in the “fall of the Church” (not to be confused with “apostasy of the Church”)!

Fall-of-the-church theory and the Trail of Blood Baptists are two entirely different things. Indeed, Trail of Blood adherents deny the fall of the church (instead they claim that Rome and Constantinople were never true churches to begin with), and they teach a variant of apostolic succession (albeit one which can easily be disproven historically).

This video provides a helpful analogy:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-QnBWL_d-5A

“Paula the Restorationist Home Inspector” claims that the house in the video stopped existing for 80 years because the people who were living in the house were doing the wrong things. Then, when her uncle Floyd moved in, the house started existing again because he did things the right way. This is analogous to the fall-of-the-church theory.

A Trail-of-Blood Baptist, on the other hand, would claim that the house in the video is actually a counterfeit, no house at all, and that for the past hundred years the REAL house was actually that tiny shack in the backyard that hardly anybody ever saw.

Unlike mainstream Protestants, Trail-of-Bloodists DO believe in a form of apostolic succession (via an unbroken trail of adult baptisms), and as a result they are not Protestants (they usually don’t self-identify as such, either). They don’t believe the Catholic/Orthodox church “fell”, but rather they claim it was never a true church to begin with. Many of them (such as Jack Hyles, Jack Chick, etc.) claim it was founded as a counterfeit church by Constantine to compete and persecute the “real” Baptist church. It’s an ecclesiology straight out of The Da Vinci Code. Granted, anyone who knows anything about ancient history should know this hypothesis is all a bunch of BS.

Jacob/Olaf,

I’ve been reviewing your comments on this blog and decided that I need to set some guidelines for your comments: (1) Stay on topic; (2) Anything off topic will be blocked; (3) Red herring objections are especially off limits; (4) Ostentatious display off your “scholarship” will be discouraged. Constructive contributions to the Reformed-Orthodox dialogue will be welcomed.

Robert

Olaf,

// Okay, let’s pretend for the moment that the Protestants were really revolutionary Trail-of-Blood Baptists. //

This is just a straw man rehash of Robert´s argument: nowhere, did he conflate the Reformed “faith” with anabaptist theology! Nevertheless, he demonstrates that a Reformed view of Church history – consistently applied – is nearly as radical in its rejection of historic Apostolic Christian truth. Robert defined the “fall of the church” as the general belief/notion that “after the Apostles died the early Christians strayed from the original Apostles’ teachings and practices.” It´s not necessary that one hold to an “anabaptist” view that the Church fell into “rank apostasy” for Robert´s points to be valid!

// Could we at least interact with the supreme apex of Protestant thought? Guys like Turretin, Richard Muller–those guys. //

This is a prime example of a red herring: sidetracking the conversation with logically irrelevant information. Would interacting with specific Reformed theologians (as fascinating as that may be ) – in any way whatsoever – invalidate Robert´s critique of Protestantism´s self-justifying docetic ecclesiology, since Turretin and Muller – being Reformed theologians – held to the exact same (albeit nuanced) conclusion (i.e. BOBO) ? Indeed, all Protestants must hold to a form of BOBO to claim any semblance of legitimacy! Ad hominum attacks against Terrtullian (you admitted to “smearing him”) have no bearing whatsoever on the substance of his arguments! Argument three – personally – was so overwhelmingly powerful as a Presbyterian (having grown up Baptist), that I began to realize that my church and all of Protestantism was truly a false and arrogant aberration, sharing little to nothing in common with historic Christianity. Why do the Oriental Orthodox and the Assyerian Church of the East – having been mostly outside of the Roman Empire – all share the exact same Apostolic beliefs as us, with the one exception of the language used surrounding Christ´s person/natures? The answer can only be that we share the common Apostolic deposit.

// Shucks, even Bradley Nassif said one has to read Richard Muller in order to understand Protestant thought. //

I´m not denying this; but next time, could you provide a reference for such statements?

// I know the response: “You can’t know Orthodoxy by books, you have to experience it.” That may well be so, but that line also serves to stifle any real discussion or critique. //

In past posts, you´ve claimed to have studied Orthodoxy for years in order to reject it in favour of remaining Protestant. However, I´m curious whether this was indeed merely a dry/hands off/”intellectual” investigation into Orthodoxy or whether you spent months actually attending the services? If the former, then your disdain for “experiencing” Apostolic Christianity remains a valid critique of your questionable a priori only approach. Christ invites us to come and see (John 1:39) (i.e. experience) and Orthodoxy has always had this approach – long before the disembodied, docetic, and rationalistic Protestant approaches to truth and spirituality were invented.

I attended divine liturgies, if that is what you are asking. Granted, there were more than intellectual reasons why I could not join Orthodoxy.

Olaf,

// I attended divine liturgies, if that is what you are asking. //

Attending only a few Divine Liturgies is extremely minimal for someone claiming to have studied Orthodoxy for a few years. In the same way that we don´t consider “theologians” to be those with M.Divs or academic degrees – but rather as Evagrius Ponticus expained, “If you are a theologian, you will pray truly. And if you pray truly, you are a theologian.” (Treatise On Prayer, 61) (i.e. communes with and experiences God ) So too, your a priori “intellectual” western/Protestant approach to Orthodoxy is based on a false presupposition on how one can learn truth about God in specific and spirituality in general. Did you attend any of the daily offices: Matins, Vespers, Compline, or Nocturnes? Did you attend a Presantified Liturgy or the services of Holy Week?

Well, you don’t know either my logistical situation nor familial obligations as to how my week and time is spent.

***Did you attend any of the daily offices:***

Local parish didn’t have them. In fact, one Sunday they weren’t even open.

***Did you attend a Presantified Liturgy or the services of Holy Week?***

Yes.

Once again I am going to have to side with Olaf on this one. The last time I was here I heard the same request to go to an EO divine service to see that the church is true. I am obviously missing something because when they say that I think what I am hearing is something different than what they mean. I really don’t know how else I can say this but, I can have a profound religious experience at a mosque as well as the Ganges River. And if Satan can disguise as even an angel of light then how much weight can we put into our spiritual experiences? It sounds eerily similar to the Mormon burning in the bosom for my comfort. So obviously I am misunderstanding what is being said here.

Mike, perhaps it would be easier to understand the Orthodox insistence that there can only be understanding of its faith to the extent that there is participation in its life if we consider that likely, on reflection, most conservative Christians would expect someone from outside Christian faith altogether would have to look at most Christian teaching from within the Christian tradition to begin to really understand it. Would you accept Hindu assessments of the nature and “divinity” of the Person of Christ, or Muslim understandings of the Christian teaching of the nature of the Holy Trinity?

Though the differences between different Christian traditions are, obviously, far more subtle than the divide between Hinduism and Christianity, from an Orthodox perspective they are still there and need to be reckoned with in a similar way. This is especially so, it seems to me, the more distantly different Christian traditions existing today are related. Thus the East/West division, by virtue of its place and significance in the history of those groups tracing their roots to the united orthodox and catholic Christians of the first millennium represents, in many ways, the greatest paradigm shift to undergo in the interpretation of Scripture and the Christian life–especially for modern Protestants of any stripe. Inevitably, to regard the teachings of one faith from the context of another, is to distort its teachings. Most pious, thoughtful Christians have discovered from their own experience that understanding Christian faith and the Scriptures aright and in any real depth comes about as a result of earnest study and effort in order to put the teachings of the Scriptures into practice in one’s own life along with careful attention to the insights of those who have lived its teachings most faithfully–and so it is with Orthodoxy.

Karen, with all due respect hear what you are saying but I stand by what I said.

Mike, what you said appears related to “attending a service” as a (superficial, psychological?) “experience” only, and in that respect I can’t disagree with you. (Correct me if my interpretation of your comment is off-base.) My comment was to point out that this is not what Orthodox generally mean when they point out participating in Orthodox life (such as attending its services and following its way of prayer and fasting, etc.) is necessary for properly understanding its teachings. I understand that the way this is sometimes stated, especially given many of the cultural presuppositions within modern American consumer-driven Christianities, can give that impression, though.

Thank you for clarifying. However, you said, “participating in Orthodox life (such as attending its services and following its way of prayer and fasting, etc.) is necessary for properly understanding its teachings”. I’m not being snarky when I say this, but this sounds very much like Mormons I have encountered. They say that the only people who can understand their religion are Mormons, so don’t ask outsiders. And they also go on about testimony, that if you don’t have one then bear it anyways and you will eventually get one. So what then, I join their church so that I can find out what they truly believe and try to understand more through the service and prayer? I am not at a point in my life where I can devote a few years to investigating a church from inside. I really do respect what you are saying but I disagree unfortunately.

OK, I posted here once before while looking at Reformed, Lutheran, Anglican and Orthodox churches from an evangelical protestant background, and I can now say that I have found my home in Lutheranism. Unfortunately, I have to side with Olaf’s point here even though I am not at all excited to do so because, just based on this page, he strikes me as one of those people who post (no offense hopefully). This article does not address Reformed doctrine in particular but rather “Protestants”, in a very generic way. This is not the first time I have seen EO use the all-encompassing categories of “Western” or “Protestant” while actually only addressing one arm of that umbrella. I know that if by “Protestants” is meant “Lutherans” then both Martin Luther and I flatly reject this article. The Book of Concord quotes the Church Fathers all over the place and, unlike the Reformed, we commemorate the saints through the liturgical year from Clement of Rome to Luther and beyond. And this may actually apply to the Reformed, I do not know, but I do know that unlike the other Reformers, Luther actually wanted to reform the Church all the way up to the Papacy rather than pick up his ball and take it home like Zwingli, Calvin, and the radical reformers. But if this article is addressing what we would call today evangelical protestants then I wholeheartedly agree. I just think a great deal more of clarification was needed here in defining terms because I know the EO hate to be mischaracterized as well.

Mike,

It’s nice to know we have Lutherans reading the OrthodoxBridge! Much of my conversation is with the Reformed tradition because that is the one I’m quite familiar with. I am less familiar with the Lutheran tradition. Maybe you can answer this question for me: Do the Lutherans agree with Tertullian’s definition of orthodoxy as he presents it in Prescription? And do they claim apostolicity on the same grounds as that used in Prescription, that is, they can show a list of apostolic succession for their bishops?

Robert

” Do the Lutherans agree with Tertullian’s definition of orthodoxy as he presents it in Prescription?”

I do indeed think that they would, but I am not a doctor of the church. When reading many of the early saints they would say that were it not for the fact that doctrine and practice were ubiquitous throughout the lands we would not know what is catholic. Lutherans agree with that with a very important caviot and that is the subject of Roman abuses. But the reformation to Lutherans was a removing of barnacles from the ship due to lack of cleaning, if that makes sense. And Lutherans are Augustinian Western Christians at their core, which will be frowned upon by Eastern Christians. And of course Lutherans believe in Sola Scriptura (not SOLO scriptura of the protestants) but the catholic saints are still used as an authority but nowhere near en par with Scripture. To Lutherans the reformation was an attempt to get back to Augustinian Western Christianity and remove all practices and teachings that were blatantly contradicted by Scripture. However, an important distiction between Lutheran and Reformed churches is that Reformed churches observe the regulative principal of Scripture whereas Lutherans would observe the formal principal of Scripture. In other words, Calvinist only can do what Scripture commands while Lutherans only can NOT do what Scripture blatantly contradicts, if that answers the question.

“And do they claim apostolicity on the same grounds as that used in Prescription, that is, they can show a list of apostolic succession for their bishops?”

When Lutherans moved to America after being forced to join churches with the Calvinists in Germany (which was religious persecution to them, and rightfully so) there was an episcopal polity in place. The story is very interesting how this became replaced with a congregational polity so I will allow for the readers to do the research on that. Lutherans observe the office of the ministry and no one takes this honor onto themselves unless they are call. For American Lutherans the episcopacy is not required to be called into office of ministry to administer the sacraments. Also, the Book of Concord only adddresses the episcopal polity and assumes that it would continue henceforth.

Mike,

You didn’t quite answer question #2 in which I asked if the Lutherans can show a list of succession for their bishops. Here for example is a list of succession for the Antiochian Orthodox Archdiocese. http://www.antiochian.org/patofant/primates This meets the criterion set forth by Tertullian, can you show us something similar?

Robert

I guess, if someone had a list of who ordained who going back to the German migration, then going back to the Lutheran reformers, then back to the See of Rome, then if the Romans have a comparable list going back to the apostles, then yes. The thing is that Lutheran congregationalism is not like non-denominational congregationalism because in those types of churches someone just decides to start a church and be a pastor without any calling whatsoever. That is not okay and unscriptural. So, it is explicity understand that every ordained minister goes back to the holy apostles. I guess that American Lutheranism is more concerned with the office of the ministry without being concerned about knowing the exact line of succession. That’s my take on it, but once again I’m not the poster child for Lutheran scholasticism.

Do Orthodox consider the Anglicans to have a valid and recognized Apostolic Succession?

Short and simple answer: no.

The longer answer is that there was a time when Anglicans and Orthodox were looking into a merger. Bishop Raphael Hawaweeny (Antiochian Orthodox) of Brooklyn once belonged to the Anglican and Eastern Orthodox Churches Union until he became aware of the significant differences between the two traditions and subsequently wrote a letter stating his reasons for resigning from that organization. So far as I know no rapprochement between the Anglican and Eastern Orthodox traditions has ever proved successful.

Robert

I have read a Catholic explanation of the succession question for the Anglican Church. Apparently the Anglican Ordination service was changed to reflect a Memorial view of the Eucharist. From the Roman point of view, since a ‘defective formula’ was used for over a generation, valid priestly orders died out in England.

I could not answer whether this would be viewed as problematic in Orthodox thought, or even what thought has been given. Perhaps restoration of communion might, by economia, be judged to re-invigorate the Anglican Apostolic succession. But that likely will be a moot question, the way that things are going.

The Church of Sweden has actually maintained apostolic succession to this day (and is the only large Lutheran church to have done so); although arguably their recent decision to start “ordaining” women to the episcopate calls their future into question.

One thing I don’t understand is why other Lutheran churches didn’t maintain apostolic succession. If Lutheranism is more conservative with respect to tradition (which it is) than Calvinism or the radical reformers, why didn’t all the Lutherans follow the Swedish model? Was it possibly the result of crypto-Calvinist influence (Melanchthon)?

One of the reasons is that, as I understand it, in some cities and areas there was a dearth of “apostolically ordained” ministers and the people (church, laity, clergy, what have you) realized it was more important to have the gospel preached than to be able to trace back an apostolic line (which is in line with John the Baptist’s warning to those who say “We have Abraham as our Father”).

Thank you, Mike. I am really a nice guy. In fact, I’ve even tried to moderate my tone (and I think I have). It’s just when it’s 10-1 and I make pointed arguments, it comes across caustic. If so, apologies.

True enough, I know that feel. Well on monergistic soteriology I’m with you aside from “limited”, but most things sacramental I’m with them.

But I would still like the point to be acknowledged that “Protestant” is entirely too broad to be properly applied to this article.

The information on Lutheran churches and the apostolic succession (of bishops) presented in comments on this thread is largely incorrect historically. The only Lutheran church that purportedly preserved such a succession at the Reformation was that of Sweden (from which other Lutheran churches later derived their succession of bishops), but the simple facts of the case render that of Sweden much more “iffy” than that of the Church of England.

In 2003 I wrote a brief essay on “the Swedish succession” for an Anglican friend. I do not wish to clutter someone else’s blog, uninvited, with an essay of that sort, but should anyone here have any interest in it, I would willingly forward a copy of it. My e-mail address is tighe.at.muhlenberg.edu.

And regarding the Porvoo Communion, don’t those state churches (CoE, CoS, etc.) regard apostolic succession more as a symbolic aspect of the church rather than as a necessary mark of the one true church as the EO view it?

I don’t think the ‘Fall of the church’ or the ‘Trail of Blood’ theories are the only possibilities for those of us who haven’t swam the Tiber or the Bosphorus. Another way of picturing the Church and the need for reformation is that of a garden which needs weeding: it’s the same garden before and after it’s been weeded. Likewise, the Anglican Reformers described the Church as being the same Church before and after the removal of Roman innovations. (Mike’s analogy about a ship/barnacles is also a good one). In fact, those Anglican divines in the 17th century that most consistently looked to the early fathers found themselves at odds with both Puritans and Papalists.

Good observations, Doubting Thomas. Building on your analogy, I suppose the question we Orthodox would like to raise for other Christians (here offering this teaching of Tertullian as a guide) is how, then, does one decide what are “weeds” and what are legitimate plantings (dogmatic teachings and their application in rites and liturgy) that must not be uprooted if we are to preserve the faith entire and intact? Let us just take as our examples, as Robert has suggested in several of his posts, the understanding of the nature of the Church’s most fundamental constitutional rites–Baptism and the Eucharist. Using your example of Anglicans, even Anglicans today with whom at points in their history Orthodox have had much in common, don’t agree amongst themselves how these should be understood, much less agree with Orthodox teaching and the teaching of the early Fathers.

Karen,

You asked how one decides what the ‘weeds’ are that need to be removed in reforming the Church. The answer is to look back at Scriptures as interpreted by the early patristic consensus. Many Anglicans, for example, continue to do this, while many others latch on to a different partisan system (Anglo-Calvinism or Anglo-Palpalism, for example) or even another worldview (ie secular progressivism) as their guide for interpreting Scripture and/or ‘reforming’ (reinventing) the faith.

Quite right. Is it any surprise, I wonder, that many Anglicans today who choose the traditional path of resourcing themselves in the early Fathers end up becoming Orthodox? 🙂

It’s no surprise that some Anglicans who value the fathers end up Eastern Orthodox, particularly those in jurisdictions (such as TEC) that are overrun with apostate, liberal wackiness. For those surrounded by such wackiness, I can certainly understand their reasons for swimming the Bosphorus–it’s certainly better than sinking into a neopagan swamp. Others, who are convinced by papal claims, go to Rome; others, however, go into more conservative, traditionalist Anglican jurisdictions. I myself seriously considered becoming Eastern Orthodox for about 3 years (and was even a catechumen for couple of months) before landing in a traditional Anglican Church for reasons I listed below in the ‘Calvinist revival’ thread.

I was an Anglican for many years and eventually went the Continuing Anglican route when I got fed up with the liberalism I otherwise found in Anglicanism. But whilst I still love much of Anglicanism, the Continuing Anglican churches left me underwhelmed. If you can find one that believes in apostolic doctrine and practice as taught by the Fathers and renounces innovations such as women priests, it may be wonderful at the local parish level. But it will be a small, relatively irrelevant (unfortunately) stream that lacks the universality of the catholic Church described in Scripture, the Councils, and the Fathers.

Once I finally went Orthodox, I felt so relieved to be finished with the internecine battles of Anglicanism.

For those enamoured with the Anglican rites, I would suggest the Western Rite of Orthodoxy. Or better still, fall in love with the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom. It is uniquely beautiful.

Eric,

Thanks for sharing this insight. I too find the Western Rite beautiful. I know that the Antiochian Archdiocese is involved in starting up Western Rite mission.

One problem I have with Continuing Anglicanism is that there is no formal excommunication of the TEC for its heresies. This means that even if you are a conservative traditional Anglican, you are still in eucharistic communion with the TEC liberals. This is one of the profound implications of Tertullian’s definition of orthodoxy.

Robert

“Using your example of Anglicans, even Anglicans today with whom at points in their history Orthodox have had much in common, don’t agree amongst themselves how these should be understood, much less agree with Orthodox teaching and the teaching of the early Fathers.”

I think that’s a true observation. The main difference between Anglican and Lutherans in my opinion is that Anglicans are more concerned with the uniformity of worship while Lutherans are more concerned with the uniformity of doctrine. Lutherans take discerning the body and blood of our Lord very seriously and will not allow for non-Lutherans to participate at the altar, or even Lutherans if they reject orthodoxy. However, Anglicans will allow for non-Anglicans to participate at the altar. I’m good friends with the local ACNA priest who is also the godparent of my child and he is very anglo-catholic and I asked him what if the Book of Common Prayer disappeared from the earth and so did Canterbury would Anglicanism survive? his answer was that Canterbury was optional but the service book was necessary. So we see necessities of both church bodies.

“I suppose the question we Orthodox would like to raise for other Christians (here offering this teaching of Tertullian as a guide) is how, then, does one decide what are “weeds” and what are legitimate plantings (dogmatic teachings and their application in rites and liturgy) that must not be uprooted if we are to preserve the faith entire and intact?”

I would say that those things (and in the case of Anglicans and Lutherans would be the Roman abuses) that are blatantly contradicted by Scripture as understood by the church fathers are to be weeded out. As I have said before the Book of Concord quotes the saints all over the place, and I would argue that every doctrine held by the Lutherans can be substantiated by the saints, while at the same time saying that every doctrine held by the Eastern churches can also be substantiated by the saints as well. So we observe what the fathers before us have to say but at the end of the day the Scriptures are sufficient for defining necessary doctrines for salvation. But I can tell this will not sit well with the audience here so I will stop writing now.

Mike,

As an Anglican who has a lot of appreciation for Lutheranism, I wanted to respond to some of your comments.

“The main difference between Anglican and Lutherans in my opinion is that Anglicans are more concerned with the uniformity of worship while Lutherans are more concerned with the uniformity of doctrine.”

–Sadly, this seems to be the case (although there are some liberal Lutherans as well), and it’s something I admire in conservative Lutheranism. I think if Anglicans would actually stick with their formularies (BCP, 39 Articles and Homilies) there would be more uniformity in doctrine than there is now. Regarding uniformity in worship, I sadly can’t even say that is the case for many ‘Anglican’ churches either anymore: some are nosebleed High; some are snake-belly low, some are ‘charismatic’, and some are just full of new-age goofiness.

” Lutherans take discerning the body and blood of our Lord very seriously and will not allow for non-Lutherans to participate at the altar, or even Lutherans if they reject orthodoxy.”

As they should. Interestingly, however, the LCMS parish I visited several years ago invited non-Lutheran visitors to take communion as long as they believed in the real presence of the body and blood of Christ.

“However, Anglicans will allow for non-Anglicans to participate at the altar.”

Yeah, I have mixed feelings about this one. In the ACC parish I used to be in, one could receive communion if one was confirmed or desirous of confirmation. In the ACNA parish I’m in now, it’s for all baptized believers. On one hand, objectively I can think closed communion is correct historically (and is spiritually safer); on the other, my wife is NOT Anglican (but is a commited Christian) but is able to receive communion in our parish.

So how do Easter Christians regard Lutherans and Anglicans: 1) You guys are the church; 2) We’re not saying you’re not the church, but we’re not saying that you are either; 3) You guys are outside the church.

I believe the “official” answer you will often hear is like your #2: “I don’t know. We know where the Church is; we don’t know where it is not”. Everyday we pray to a Holy Trinity “who are in all places and fill all things”, so we recognise that God is not limited to the (Orthodox) Church. But unlike Roman Catholicism, Orthodoxy does not venture to define who outside of the Church is somehow mystically in communion with it.

Based on my experience, I think you will find that most Orthodox will not doubt that other traditional, Trinitarian followers of Christ are indeed Christians, albeit lacking the fullness of the apostolic faith. I have heard several Orthodox leaders such as Met. Kalistos Ware say as much.

I’m comfortable with that. I particularly like where you said, “Orthodoxy does not venture to define who outside of the Church is somehow mystically in communion with it”. I appreciate the fact that Orthodoxy can see a logical conclusion but not draw that conclusion to be true based on that alone. Calvinist often (well, always) criticize Lutherans for being inconsistent in aspects of their theology, Lutherans feel comfortable holding seemingly inconsistent things as paradox while Calvinists have no problem connecting the dots, so to speak.

Eric, I think your answer is largely true with regard to non-Orthodox Trinitarian Christians as individual believers following Christ in good faith according to what they have been taught outside the Orthodox Church. I know those of us from non-Orthodox Christian backgrounds certainly acknowledge the work of the Holy Spirit on a personal level in the non-Orthodox Christians of our acquaintance (in my case, insofar as my own level of maturity–or lack thereof–allows me to discern this!). It is probably more accurate to say the answer is #3, though, if by “Lutherans” and “Anglicans” you are also intending to also identify their institutions and official doctrinal statements, rites, etc.. The boundaries of what is properly considered “the Church” in this sense within Orthodoxy is who the Orthodox are in actual Eucharistic communion with. With regard to the more charismatic sense of the Church’s boundaries, we are as you stated, agnostic, leaving to God what can only properly and fully be known to Him. Hope that makes sense.

*Eastern

Since this site is devoted to Calvinism and Orthodoxy I have something interesting to add. I first posted on this site yesterday and ironically enough a few hours ago a podcast was released on Eastern Orthodoxy by one of my favorite people, a former Calvinist who converted to Lutheranism. I think he does a good job not mischaracterizing Calvinists and even Baptists or Carismatics so I feel he has also given a fair representation of the Orthodoxy. http://justandsinner.blogspot.com/2014/02/an-introduction-to-eastern-orthodoxy.html

This is a murky subject for Lutherans and Calvinists as they try to maintain that their faith is consistent with the orthodox early church. For radical Protestants, statements from Tertullian and other ECFs mean nothing because they don’t even pretend to care what they say.

For Calvinists, there are huge problems in their attempt to claim continuity with the Church of early centuries. They don’t like the Theotokos, yet the title was conferred to her by a very early and important council that the Reformed supposedly hold to. The fact that the title “Mother of God”, a term that many Reformed are clearly uncomfortable with, was conferred on St Mary shows that devotion to her was a very early practise in the Church. Calvinists seem to hold that by the time of Nicea II and the iconoclastic controversy was settled in favour of those who love icons, the Church must have fallen away completely. So by the 8th century the Church appears to be in complete heresy until the Reformation many centuries later.

I just don’t know how a Calvinist can claim this with a straight face. They clearly don’t like some decision of the Councils, while vigorously defending others. It seems like a very inconsistent way of going about things.

Simon,

Thanks for joining the conversation! You made some good points.

Robert

I think this gets back to the Calvinist view of the regulative principal of worship. For them, since the New Testament mentions nothing of religious images therefore they are not allowed. However, Christ himself took on an image—the image of a man. The Temple was elaborately decorated with all sorts of images, does this contradict the command in the Decalogue? Certainly not. Religious images are ordained by God Himself and ancient and catholic.

I agree with you Mike. My point was that Calvinists can’t claim continuity with the ancient church whilst cherry picking decisions from the Great Councils. The implications are obvious: the Early Church believed and emphasized things that Calvinists reject outright or are suspicious of. My two examples show this. They are uncomfortable (to say the least) with the Theotokos. They reject completely the holy icons. They don’t have Bishops and priests, which every Communion that traces their heritage to the Apostles has. I fail to see how they think they can claim a common faith with the Apostles and Fathers.

As a former Calvinist, I have had to repent of buying into the pick and mix underpinnings of Reformed systematics.

Sola scriptura is essentially a humanist construct; not a faithful return to the biblical sources. All texts, whether inspired or not, require an interpretative framework. If that framework is developed in an a-historical manner, using primarily forensic and scholastic approaches to written material and by ignoring 1500 years of the history of hermeneutics within the Christian community, the reformational understanding of the Bible and the Christian life is what might emerge. An emphasis of head over heart. An unbalanced understanding of salvation, utterly overplaying the punitive element, which is seen in scripture but which is by no means predominant. A system of doctrine that strives so hard to be neat and internally consistent, but can only pretend to be so by ignoring or, by slight of hand, reinterpreting any troublesome counter-witness within Scripture. A mistrust or dismissal of anything that might impose mystery upon the contemporary church – mystery and miracles were okay back then, but they don’t happen now.

I find it somewhat ironic that pious and (I’m sure) well-meaning lawyers could play so fast and loose with what is admitted into evidence and how such evidence is used.

To Simon’s point, the Reformed do not really accept any Ecumenical Council in its entirety and always through the lens of one of their own long-form confessional documents. Essentially, the Reformed position is to accept the “cardinal doctrines” promulgated by the first six ECs, but to ignore almost everything else in the ECs’ pronouncements, especially anything that is incompatible with their a priori positions regarding church governance and worship.

In the polemics of the Reformation, I can understand why Calvin would cite the fathers against the contemporary Roman Church; but his citations are selected primarily to bolster his arguments, and not genuinely to discover the underlying truth. In any event, his default father is Augustine, and we know what a mess his understanding of the Fall has made in the Western Church.

So selectivity with the Biblical and Patristic evidence is a characteristic of the Reformation. History being largely inadmissible into evidence is another.

Great post.

I will have to read more about Calvin’s usage of the Patristic material. My understanding is that his citations came predominantly from Augustine.

This seems to be a theme in the West. Giving undue influence to a central figure. From Augustine to Anselm to Aquinas (perhaps it has something to do with the letter “A”!), these figures have been central in shaping Western theology – away from orthodoxy I would contend. Perhaps this is why Catholics gather around only 1 central figure, the Pope. Protestants have either Luther or Calvin (called Lutherans or Calvinists). And today there are countless celebrity evangelical ministers who are gurus to their own congregations.

I think this is because, in the West, the faith has been excessively intellectualized and theology has become an ideology. It mirrors other ideological movements that centre around the ideas of a certain individual. That’s my take on it anyway. Perhaps it would be a good book or dissertation topic!!

“An emphasis of head over heart…and a distrust of mystery.”

Indeed that is true of Calvinism, and also of other movements including Campbellism. Not to mention liberal Protestantism, exemplified by Bishop Spong, that seeks to expunge anything “irrational” from Christianity.

It’s far less true of Lutheranism (in which there is a prominent mystical element, exemplified early on by Johann Arndt and later coming to the fore in Pietism). Early Methodism, with its revivalist underpinnings, originated as a reaction against Reformed cerebrality, and Pentecostalism carried that backlash even further (it’s often said Pentecostals have a heart but no head). And then there are the Independent Fundamental Baptists (Jack Hyles, Jack Chick, etc.) who tragically have neither head nor heart.

There’s a Wizard of Oz joke here somewhere, I’m sure.

Selective for sure….have any of you guys heard of R. J. Rushdoony and his “Chalcedon Foundation”? The group promotes reconstructing the U.S. as a theonomy (which is sort of like Calvinist Sharia). If you read the explanation on their website for why they named themselves Chalcedon, they offer a ridiculously twisted (re)interpretation of the Council.

Ironically, Rushdoony was Armenian and the Armenian Apostolic Church is officially non-Chalcedonian, though they did remain in communion with the Chalcedonian Orthodox for five or so centuries afterward, if I’m not mistaken. Back then, it was not considered as important for churches outside the Roman Empire to affirm the councils, as the councils themselves officially covered only the churches within the Empire, hence the name ecumenical (literally “imperial”). Likewise the Assyrian “Nestorian” church remained in communion with the Orthodox churches within the empire until around 750, which is why Orthodox, Catholics, “Nestorians” and Orientals alike consider Isaac of Nineveh a saint.

Kind of tragic how Rushdoony sold his Armenian Apostolic birthright for a mess of Calvinist pottage.

You know Anastasios, you make a good point in recognizing the Nestorian-Calvin connection.

Getting back to the subject of religious images, what is the connection between the Nestorians, Calvinists, and Evangelicals? The fact that they all deny the incarnation in one way or another. The Nestorian error regarding the incarnation is well know by us all, but the Calvinist and the Evangelicals err regarding the incarnation in their view of the sacraments (or more correctly the lack thereof). Calvinists claiming that Christ is present only spiritually in the Lord’s Supper by saying that “the finite cannot contain the infinite” is a flat-out denial of the incarnation because our Lord did exactly that when He took on flesh. The Evangelicals don’t even recognize that Christ is spiritually present in the Eucharist. And when you walk into a Nestorian church to this day it will look exactly like a Evangelical church with only one bare cross at the altar.

Denial of the incarnation is simply neo-Gnosticism in which all things physical are bad and only the spiritual is good. There are no new heresies, only repackaged old ones. Thank goodness that Mary wasn’t a Calvinist or else she would have only had a spiritual birth.

Simon, you said, “This is a murky subject for Lutherans and Calvinists as they try to maintain that their faith is consistent with the orthodox early church” and then point to Mother of God and religious images as supporting evidence. I would agree that both of these smack against Calvinism but they obviously do not muddy the waters for Lutheranism.

Then you say that since Calvinists don’t have bishops and priests (and I’m assuming that you are still lumping Lutherans in with this) therefore they cannot claim a common faith with the Apostles and Fathers. Apostolic Succession is a necessity for the church according to the fathers but not an absolute necessity. St Augustine said while writing to the Manichaeans, “For in the catholic church, not to speak of the purest wisdom the knowledge of which only a few spiritual men attain in this life … (since the rest of the multitude derive their entire security not from acuteness of intellect but from simplicity of faith)—still even if I do not speak of this wisdom that you do not believe to be in the catholic church, there are many other things that most justly keep me in the bosom. The consent of peoples and nations … Its authority … The succession of priests keeps me … Ans so, lastly, does the name itself of ‘catholic’ … But with you, where there is none of these things to attract or keep me, the promise of truth is the only thing that comes into play. Now if the truth is so clearly proved as to leave no possibility of doubt, it must be set before all the things that keep me in the catholic church. But if there is only a promise [of truth] without any fulfillment, no one shall move me from the faith that binds my mind with ties so many and so strong to the Christian religion.”

Even as a Calvinist I thought that Rushdoony’s lot were loonies, but some of their theocratic stance was inherent within the political structure of Calvin’s Geneva.

I didn’t know that Rushdoony began life in the Armenian Apostolic Church. Indeed a tragic conversion.

Even on doctrine, Calvinists, Lutherans and Anglicans will often say they affirm only the first four ecumenical councils.

Why just four? I have no idea. If the Reformers had drawn the line at three, that would have provided them with an opportunity to enter into communion with the Orientals, and if they’d drawn it at two, they could have entered into communion with the Assyrians (“Nestorians”), who incidentally also have a problem with the name Theotokos. But there are no ancient churches that accept just four councils. The Reformers ended up all on their own on this one, without any strategic allies from older traditions.

Yeah, good point. I mean I’ve read the canons of the seven councils and I don’t remember coming across anything worthy of being unscriptural. But I think for those churches that you named, they really don’t even hold to the first four in the way that the ancient church held to the seven. They more or less focus on the first four because the doctrine of the Holy Trinity became purified as heresies and heretics became exposed to the light. So in my understanding the reformers saw the Trinity in those council rather than the fact that they were Ecumenical.

Doubting Thomas, thanks for the referral back to the Calvinist Revival thread.