On 3 July 2012 the blog site Outlaw Presbyterianism criticized the OrthodoxBridge for its use of the Vincentian Canon. It’s sad to see a friendly inquirer take a more antagonistic stance towards Orthodoxy, but a number of points were raised that can help further Orthodox-Reformed dialogue.

On 3 July 2012 the blog site Outlaw Presbyterianism criticized the OrthodoxBridge for its use of the Vincentian Canon. It’s sad to see a friendly inquirer take a more antagonistic stance towards Orthodoxy, but a number of points were raised that can help further Orthodox-Reformed dialogue.

He writes:

The one common refrain at OrthodoxBridge is that Protestants can’t find any of their distinctives in the early Fathers of the church. This charge bothers some people. However, like a judo artist, I will redirect the blow. This will not prove that Protestantism is correct, but it will show that if the charge is correct, not only is Protestantism false, but so is Orthodoxy.

Because Outlaw criticized our use of the Vincentian Canon, this blog posting will focus primarily on the Vincentian Canon. I hope to show that the Canon reflects the historic Christian faith and as such is integral to Orthodoxy. Part I will contain my response to the criticisms made by Outlaw Presbyerianism in his posting and Part II will discuss the challenge that the Vincentian Canon poses to Protestant theology.

Background

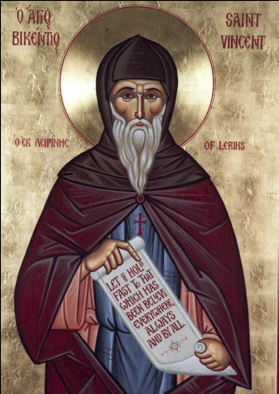

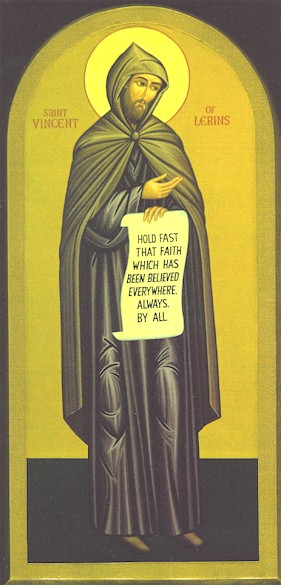

The oft quoted “Vincentian Canon” is the Latin phrase: “Quod ubique, quod semper, quod ab omnibus creditum est” (That Faith which has been believed everywhere, always, by all). It comes from The Commonitory (ch. 2) by Vincent of Lérins.

Moreover, in the Catholic Church itself, all possible care must be taken, that we hold that faith which has been believed everywhere, always, by all. (Commonitory ch. II, §6; NPNF Series II Vol. XI p. 132)

The word “canon” refers to a standard or measuring stick. It provides three criteria by which one can determine whether a doctrine was orthodox or heretical. Vincent did not invent the “canon” named after him. He summed up in elegant Latin the longstanding theological method used by the early Christians.

The author of the Commonitory used the pseudonym “Peregrinus”; he was later identified as Vincent of the monastery of Lérins, a group of islands near present day French Riviera. Vincent’s living in the Western half of the Roman Empire would explain why the Commonitory was written in Latin. He lived in the fifth century and was a contemporary of Augustine. He wrote the Commonitory in protest against what he considered to be novelty of Augustine’s teaching on predestination (see Pelikan Vol. I pp. 319-324). It should be noted that Vincent lived long before there was a Protestant vs. Roman Catholic split. When Vincent wrote about the Catholic Church, he had in mind the undivided Church founded by Christ, not the later Roman Catholicism that Luther and the Reformers protested against. In its original sense, “catholic” meant “according to the whole.”

Part I.

Criticism #1: Did Pelikan Criticize the Vincentian Canon?

The OrthodoxBridge frequently cited the Vincentian Canon in its assessment of Protestantism. This approach examines a doctrine by asking three questions: (1) Was this doctrine held by early Christians? (the test of antiquity); (2) Was this doctrine widely held among early Christians? (the test of ubiquity); and (3) Was this doctrine affirmed by the church as a whole? (the test of catholicity). Many have found the Canon helpful for demonstrating the novelty of certain Protestant distinctives, e.g., sola scriptura, sola fide, and their understanding the Eucharist. For example, if the evidence for sola scriptura is found wanting among the church fathers then one has to wonder whether sola scriptura is part of the historic Christian faith or a later addition.

Apparently, this critique is having an impact among our Protestant visitors. Outlaw attempts to blunt our critique by invoking the well respected Yale historian, Jaroslav Pelikan, against the Vincentian Canon:

In volume 5 of his series on the History of Christian Doctrine, Jaroslav Pelikan openly challenges the adequacy of the Vincentian canon (it’s in the second to last chapter). At best it can only read, “What is [usually] believed by [many] people in [most] places.” (emphasis added)

The first thing to note is that volume five of Pelikan’s magnum opus deals with Christian doctrine in the modern era. If one wants to understand how Pelikan understood the Vincentian Canon the better place is volume one (pp. 333-339) where he discusses the Canon in its proper context.

In this particular subsection of volume five (pp. 255-265) cited by Outlaw, Prof. Pelikan was not discussing the Vincentian Canon per se but how applying the Canon was problematic for John Henry Newman (p. 258). The historian in Newman would concede that the Filioque as not a Catholic dogma in the early Church but the theologian in Newman needed to affirm that the Church always held the doctrine (p. 258). Western theologians, Protestant and Roman Catholic, were finding it increasingly difficult to invoke the Vincentian Canon in light of scholarship showing the progressive evolution of their respective doctrines. For them, the Vincentian Canon had become a “Gordian knot” with a “defect in its serviceableness” (in Pelikan Vol. 5 p. 259). It should be noted that the words in quotation marks are from Newman’s An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine (p. 12). In other words, it was John Henry Newman who was challenging the adequacy of the Vincentian Canon, not Jaroslav Pelikan.

In this particular subsection of volume five (pp. 255-265) cited by Outlaw, Prof. Pelikan was not discussing the Vincentian Canon per se but how applying the Canon was problematic for John Henry Newman (p. 258). The historian in Newman would concede that the Filioque as not a Catholic dogma in the early Church but the theologian in Newman needed to affirm that the Church always held the doctrine (p. 258). Western theologians, Protestant and Roman Catholic, were finding it increasingly difficult to invoke the Vincentian Canon in light of scholarship showing the progressive evolution of their respective doctrines. For them, the Vincentian Canon had become a “Gordian knot” with a “defect in its serviceableness” (in Pelikan Vol. 5 p. 259). It should be noted that the words in quotation marks are from Newman’s An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine (p. 12). In other words, it was John Henry Newman who was challenging the adequacy of the Vincentian Canon, not Jaroslav Pelikan.

I suspect that Outlaw fell victim to a hasty superficial reading of Prof. Pelikan’s profound scholarship and that he believed he found a convenient quote in support of his Protestant position. The lesson here is that in dealing with church history and patristic theology one must take care to read the text carefully and in its proper context.

I suspect that Outlaw fell victim to a hasty superficial reading of Prof. Pelikan’s profound scholarship and that he believed he found a convenient quote in support of his Protestant position. The lesson here is that in dealing with church history and patristic theology one must take care to read the text carefully and in its proper context.

The Vincentian Canon functions best as a rule of thumb, not as a precise formula that produces uniform results. If the OrthodoxBridge has (despite our best efforts to the contrary) implied that Holy Tradition is a nice neat, tidy consensus of all the Fathers in perfect unanimity — then Outlaw is right and we have grossly overstated the case. No, Church history is not so perfect. And we have never intended to pretend all the Fathers are in perfect agreement with each other.

Orthodoxy consists of Holy Tradition, a complex matrix of beliefs and practices. Because it is a living reality, it is marked by a certain messiness. Orthodox tradition cannot be reduced to a system of propositions devoid of internal inconsistencies. Understanding Orthodoxy means believing the Holy Spirit works in the messiness of history in the Church, the body of Christ.

Criticism #2: Where’s the Evidence for Catholicity?

I find Outlaw’s skeptical attitude and his expectation for evidentiary support troubling. He writes:

Evidentially, especially in the earlier days of the church, it’s almost impossible to prove that the people in India believed in the same thing as the people in North Africa. And if the evidence is missing, how can you make the case?

It would be great if a Gallup poll was conducted of the early Christians but it is not realistic, nor fair to impose modern twentieth century scientific expectations on the early Church. There is evidence but it is not overwhelming, nor exact. One supporting evidence can be found in Irenaeus of Lyons who was born in Smyrna, Asia Minor, studied under Polycarp, then moved to western frontiers of the Roman Empire in Gaul. He wrote:

Having received this preaching and this faith, as I have said, the Church, although scattered in the whole world, carefully preserves it, as if living in one house. She believes these things [everywhere] alike, as if she had but one heart and one soul, and preaches them harmoniously, teaches them, and hands them down, as if she had but one mouth. (AH 1.10.2; Richardson 1970:360; cf. ANF Vol. 1 p. 331; italics added)

What we have here is a Christian leader who traveled from one part of the Roman Empire to another and who found a common faith across the vast Roman Empire.

Another witness can be found in Eusebius’ Church History. This fourth century work describes Christianity’s beginnings, contains lists of bishops for various areas, and describes how the early church struggled against various heresies. A broad theological consensus in the early Church can be seen in the ancient liturgies and in the creedal formulas that were ordered along Trinitarian lines. Lucien Deiss’ Springtime of the Liturgy which contains texts of early Christian worship is recommended for readers interested in examining the evidence for themselves.

Criticism #3: The Church Fathers Contradict Each Other!

In his attempt to demonstrate the inadequacy of the Vincentian Canon Outlaw pits one patristic authority against another with respect to the one will versus the two will controversy. He notes how applying the Canon yields contradictory results.

Even worse, as Lars Thunberg points out, St Cyril affirmed “one will and energy” of Christ (Pseudo-Dionysius said the same thing). The whole point behind St maximus’s theology is the very opposite of this. Yet, if one were to “go to the earlier fathers,” would one necessarily come away with dyotheletism? Even worse, St Maximus himself hints that the greatest of all theologians, St Gregory Nazianzus, used language that was disturbingly similar to monotheletism.

The Orthodox response is that this controversy was resolved at the Sixth Ecumenical Council. Orthodoxy recognizes that church fathers as individuals may err but as a collective witness they bear witness to orthodox truth.

![]() Quite often the Vincentian Canon has been understood only with respect to the church fathers but it is broader in scope than that. Vincent appeals to the general councils as one important means of ascertaining doctrinal orthodoxy (ch. XXIII, §59; ch. XXIX, §78). The phrase “by all” in the Vincentian Canon had several meanings: (1) the consensus held among the bishops, (2) the decisions made at councils, or (3) the devotional and liturgical practices among the laity (Vol. 1 pp. 338-339). Pelikan notes: “A special mark of the universality and the authority of the church was the ecumenical councils” (Vol. 1 p. 335). The bishops present at the councils were mindful that they were part of the undivided Church. When they made decisions they did so conscious of their responsibility to safeguard the sacred Deposit of Faith. They did not have the liberty to cherry pick what they found useful or progressive.

Quite often the Vincentian Canon has been understood only with respect to the church fathers but it is broader in scope than that. Vincent appeals to the general councils as one important means of ascertaining doctrinal orthodoxy (ch. XXIII, §59; ch. XXIX, §78). The phrase “by all” in the Vincentian Canon had several meanings: (1) the consensus held among the bishops, (2) the decisions made at councils, or (3) the devotional and liturgical practices among the laity (Vol. 1 pp. 338-339). Pelikan notes: “A special mark of the universality and the authority of the church was the ecumenical councils” (Vol. 1 p. 335). The bishops present at the councils were mindful that they were part of the undivided Church. When they made decisions they did so conscious of their responsibility to safeguard the sacred Deposit of Faith. They did not have the liberty to cherry pick what they found useful or progressive.

Outlaw makes reference to Lars Thunberg’s Microcosm and Mediator: The Theological Anthropology of Maximus the Confessor to bolster his argument that the church fathers contradicted each other. The book is a fine piece of scholarship but it was not written from an ecclesial point of view. This is not a criticism of Thunberg but to make the reader aware of the genre being presented. In the early Church much of the theologizing was not done through the medium of academic discourse but through the liturgical life of the churches. The majority of the church fathers were bishops, not academic scholars. Outlaw seem to be using the church fathers much like the way Protestants use the writings of the Reformers and seminary professors to resolve doctrinal controversy.

My question for Outlaw is: Why is it that your blog posting makes no mention of the Sixth Ecumenical Council? Do you accept the decisions of that Council? By what method are you going to resolve the monotheletisim controversy as an independent Protestant or as a member of the Church Catholic?

Criticism #4: Orthodoxy as Syllogism?

Outlaw attempts to demonstrate the fallacious reasoning behind the Orthodox reliance on the church fathers by presenting this approach as an Aristotelian syllogism.

The problem is this with Orthodox internet apologists:

P1: Our practice today is part of the ancient tradition of the church.

P2: We thus appeal to this church father to prove this.

Therefore, the early church taught this and this is the tradition.

What’s the problem with this argument? The problem is that there is an epistemic gap between P2 and the conclusion. How do we know that this father is the tradition, or that tradition is thus and so (and most of the time, I don’t even grant P2. A lot of times these fathers aren’t event talking about 9/10ths of the practices that are now considered “tradition”)?

Even granting P2, at best the syllogism’s conclusion only reads: one Father of the church taught this. (emphasis added)

I find Outlaw’s reduction of Orthodoxy to a syllogism simplistic and objectionable. I don’t recall making the case for Orthodoxy with the model presented above. This is a straw man argument.

One serious flaw in the syllogism presented is the minor premise which contains the assumption that citing a single church father suffices in Orthodoxy. The emphasis on church fathers in the singular in the above excerpt is striking. When it comes to citing the church fathers, Orthodox stresses the patristic consensus, i.e., plurality. It is not enough to quote a single church father. Orthodoxy has recognized that the Fathers can err in particulars and for that reason it looks to the patristic consensus as a witness to the catholic faith. It makes me wonder: Where did Outlaw get the idea that citing a single church father suffices for Orthodoxy? Furthermore, Outlaw’s complaint that all too often appeal is made a single church father for particular tradition is vague and dubious. Perhaps he can be more specific in his complaint in a future blog posting.

Summary

There are a number of problems with Outlaw’s 3 July blog posting: (1) he misreads Jaroslav Pelikan, (2) he seems to understand Orthodox tradition narrowly as arising solely from the writings of the church fathers, (3) he makes no reference to the patristic consensus, (4) he makes no reference to church councils, and (5) his bizarre syllogism misrepresents the Orthodox theological method.

Part II.

An examination of the Commonitory will show that the Vincentian Canon is rooted in a rich theological heritage. Studying the theological method described by Vincent of Lérins will enable to us to compare the theological method of Protestantism against that of Orthodoxy.

Scripture With Tradition

Vincent argues that Scripture and Tradition are both needed for distinguishing between orthodoxy and heresy. He writes:

That whether I or any one else should wish to detect the frauds and avoid the snares of heretic as they rise, and to continue sound and complete in the Catholic faith, we must, the Lord helping, fortify our own belief in two ways; first, by the authority of the Divine Law (Scripture), and then by the Tradition of the Catholic Church. (Commonitory ch. II, §4; NPNF Series II Vol. XI p. 132; emphasis added)

We said above, that it has always been the custom of Catholics, and still is, to prove the true faith in these two ways; first by the authority of the Divine Canon (Scripture), and next by the tradition of the Catholic Church. (Commonitory ch. XXIX, §76; NPNF Series II Vol. XI p. 153; emphasis added)

This passage shows that the early Church was biblical but not Protestant in its theological method. It viewed Scripture as normative for doctrine but it did not follow sola scriptura. Vincent anticipated and refuted sola scriptura in a hypothetical scenario presented below.

But here some one perhaps will ask, Since the canon of Scripture is complete, and sufficient of itself for everything, and more than sufficient, what need is there to join with it the authority of the Church’s interpretation? For this reason, — because, owing to the depth of Holy Scripture all do not accept it in one and the same sense, but one understands is words in one way, another in another; so that it seems to be capable of as many interpretations as there are interpreters. …. Therefore, it is very necessary, on account of so great intricacies of such various error, that the rule for the right understanding of the prophets and apostles should be framed in accordance with the standard of Ecclesiastical and Catholic interpretation. (Commonitory ch. II, §5; NPNF Series II Vol. XI p. 132)

Here Vincent anticipates the potential pitfall of sola scriptura, multiple competing interpretations of Scripture. The solution to this problem is to read Scripture not individually, but corporately in solidarity with the Church. The early Church viewed Scripture and Tradition not in tension with each other but as congruent. Prof. Pelikan notes:

It was inconceivable to the exponents of the orthodox consensus that there could be any contradiction between Scripture properly interpreted and the tradition of the ancient fathers; or, more precisely, Scripture was properly interpreted with tradition. (Vol. I pp. 336-337; emphasis added)

Orthodoxy as Catholicity

In early Christianity the premium was placed on ecclesiology, not biblical studies. This is the recognition that Scripture could only be properly understood within the true church. This is the opposite of the Protestant approach which asserts that only by Scripture alone could there be a true church. Prof. Pelikan notes:

The criterion of universality required that a doctrine, to be recognized as the teaching of the church rather than a private theory of a man or a school, be genuinely catholic, that is, be the confession of “all the churches . . . one great horde of people from Palestine to Chalcedon with one voice reechoing the praises of Christ.” (Vol. 1 p. 333)

The stricture against private theory can be levied against Luther’s innovative doctrines of sola fide and sola scriptura, and Calvin’s doctrine of total depravity and double predestination.

Vincent also seems to have anticipated the Protestant tendency to split off and form new churches. Then again, it may be that Protestantism reprises the theological method of the ancient heterodox who abandoned communion with the true Church. He writes:

What then will a Catholic Christian do, if a small portion of the Church have cut itself off from the communion of the universal faith? What, surely, but prefer the soundness of whole body to the unsoundness of a pestilent and corrupt member? (Commonitory ch. III, §7; NPNF Series II Vol. XI p. 132)

Orthodoxy as Antiquity

In the early Church antiquity was held in high regard because it indicated apostolic origins. Vincent held to a nuanced understanding of “antiquity.” Antiquity by itself was not enough. Ancient orthodoxy was to be preferred over ancient heresy (Vol. 1 p. 338). Antiquity as a standard meant the rejection of doctrinal innovation. Vincent viewed doctrinal innovation as a serious threat to the life of the church.

What, if some novel contagion seek to infect not merely an insignificant portion of the Church, but the whole? Then it will be his care to cleave to antiquity, which at this day cannot possibly be seduced by any fraud of novelty. (Commonitory ch. III, §7; NPNF Series II Vol. XI p. 132)

Doctrinal innovation was understood, not just in terms of new ideas but also in terms of modifications made to a theological system, e.g., giving up or relinquishing certain teachings, or by mingling the ancient with the novel (ch. XXVIII, §58). The latter seems to stand as warning to modern day Protestants who seek to graft ancient Christian practices onto their Protestant system. He writes:

…if what is new begins to be mingled with what is old, foreign with domestic, profane with sacred, the custom will of necessity creep on universally, till at last the Church will have nothing left untampered with, nothing unadulterated, nothing sound, nothing pure; but where formerly there was a sanctuary of chaste and undefiled truth, thenceforward there will be a brothel of impious and base errors (Commonitory ch. XXVIII, §58).

Orthodoxy does not mean historical stasis. Vincent has a dynamic understanding of orthodoxy. He writes:

But some one will say perhaps, Shall there, then, be no progress in Christ’s Church? Certainly; all possible progress. For what being is there, so envious of men, so full of hatred to God, who would seek to forbid it? Yet on condition that it be real progress, not alteration of the faith. For progress requires that the subject be enlarged in itself, alteration, that it be transformed into something else. (Commonitory ch. XXIII, §54; NPNF Series II Vol. XI pp. 147-148)

But the Church of Christ, the careful and watchful guardian of the doctrines deposited in her charge, never changes anything in them, never diminishes, never adds, does not cut off what is necessary, does not add what is superfluous, does or lose her own, does not appropriate what is another’s, but while dealing faithfully and judiciously with ancient doctrine…. (Commonitory ch. XXIII, §58; NPNF Series II Vol. XI p. 132)

Orthodoxy as Eucharist

Eucharistic unity played an important part in how Vincent understood orthodoxy. He poses a hypothetical scenario in which one is confronted with a doctrinal novelty then sketches the appropriate response.

But what, if some error should spring up on which no such decree is found to bear? Then he must collate and consult and interrogate the opinions of the ancients, of those, namely, who, though living in divers times and places, yet continuing in the communion and faith of the one Catholic Church, stand forth acknowledged and approved authorities: and whatsoever he shall ascertain to have been held, written, taught, not by one or two of these only, but by all, equally, with one consent, openly, frequently, persistently, that he must understand that he himself also is to believe without any doubt or hesitation. (Commonitory ch. III, §8; NPNF Series II Vol. XI p. 132)

The recommended response is that one gives weight to authorities in Eucharist communion with the Church (see also ch. XXVIII, §72 and ch. XXIX, §77). Right doctrine cannot exist apart from Eucharist union with the right Church. The implication here is that the remedy is a return to communion with the Church Catholic, not doctrinal triangulation.

The Locus of Orthodoxy – Right Doctrine versus Right Church

Protestantism has a different approach from that of the early church to identifying the locus of orthodoxy. Protestantism situates orthodoxy in doctrine, but the early Christians placed it in the church. Again Prof. Pelikan notes:

To identify orthodox doctrine, one had to identify its locus, which was the catholic church, neither Eastern nor Western, neither Greek nor Latin, but universal throughout the civilized world (οικουμενη).

This church was the repository of truth, the dispenser of grace, the guarantee of salvation, the matrix of acceptable worship. (Vol. 1 p. 334; emphasis added)

Just as the early Church believed that one could not be orthodox in doctrine unless one was in Eucharistic union with the true Church, so likewise the Orthodox Church today insists that doctrinal orthodoxy cannot be separated from Eucharistic union with her. It is hoped that our examination of the Vincentian Canon and its proper context, the Commonitory, shows how the Orthodox Church adheres to the three fold criteria of ubiquity, antiquity, and catholciity, and how Protestantism is found wanting on the basis of these criteria.

Conclusion

Part I argued: (1) Outlaw’s allegation that Jaroslav Pelikan criticized the Vincentian Canon is based on a misreading of Pelikan, (2) his demand for evidence of the catholicity of ancient Christian doctrine unfair and unrealistic, (3) his understanding of “by all” seems to be confined to just the church fathers and excludes other sources of tradition like early councils and the early liturgies, and (4) his reduction of Orthodoxy to an Aristotelian syllogism is simplistic and rests on an erroneous premise of his own making.

Part II examined the Commonitory showing that: (1) orthodoxy consisted of Scripture interpreted within received tradition; (2) orthodoxy consisted of Eucharistic union with the church catholic; (3) heterodoxy and schism are interrelated; and (4) while progress is allowed, innovation is forbidden.

In conclusion, the Vincentian Canon reflected the rich theological tradition of the early Church. What is amazing is how much the Commonitory anticipates the theological methods of Protestantism: (1) its tendency to doctrinal innovation, (2) its propensity for schism, and (3) its disregard for Eucharistic communion as a mark of orthodoxy. The Orthodox Church of today continues to draw on this rich tradition while Protestantism is found to be wanting in light of the three markers of: ubiqutiy, antiquity, and catholicity.

I urge Outlaw and my Protestant readers to recognize that the Vincentian Canon is truly rooted in the historic Christian Faith and as such the Canon is useful for distinguishing orthodoxy from heterodoxy.

Recent Comments