Manchester by the Sea trailer

The movie Manchester by the Sea has been getting rave reviews. I saw it partly because of the reviews, but also because I used to live in the adjacent village of Magnolia. Watching the movie brought back memories of my time at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. The North Shore of Massachusetts is a string of small towns: Salem, Beverly Farms, Beverly, Manchester by the Sea, Magnolia, Gloucester, Annisquam, and Rockport. Gordon-Conwell is situated nearby, further inland, about eight miles away. Because I lived in nearby Magnolia, I was constantly driving through Manchester by the Sea. It was not so much the movie’s storyline, but the background scenery that brought the onrush of memories — the barren winter landscape covered with mounds of snow in the glaring sunlight against the crisp blue sky, the fishing boats floating in the harbor, and the distinctive New England style houses. [Note: the name of the town is “Manchester by the Sea,” not “Manchester.”]

Seeing the austere New England landscape made me reflect on how this Hawai`i-born Asian-American Evangelical began his journey to Orthodoxy. I had chosen Gordon-Conwell because of its reputation for theological conservatism and academic excellence. I also went there because it was situated in the heartland of Puritan New England, the oldest Reformed presence in America. This would put me in a position to meet Evangelicals and Liberals in the United Church of Christ (the present day descendants of the Puritans). In the early 1800s, Congregational missionaries from New England brought the Christian Gospel to Hawai`i. The original missionaries had a high regard for the authority of Scripture but by the late 1900s theological liberalism had become entrenched and dominant in the UCC. My former home church in Hawai`i was one of the few conservative churches in the largely liberal UCC. I was part of the Evangelical renewal movement in the UCC called the Biblical Witness Fellowship (BWF). I went to Gordon-Conwell in hopes of eventually becoming an Evangelical seminary professor to help the BWF bring the liberal UCC back to its biblical roots. However, in a surprising turn of events I became Orthodox!

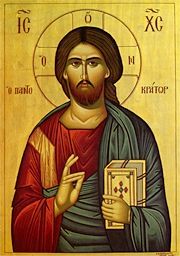

How did this happen? Despite Gordon-Conwell’s reputation as a bastion for conservative Protestantism, there were already alternative currents of thoughts flowing in the seminary. During the first week at seminary I was walking down the hallway of Main Dorm, to my surprise I saw an icon of Christ on one of the student’s door. Jim was not Orthodox but a member of the Assemblies of God, a Pentecostal group. Seeing this icon would mark the beginning of the many other surprising encounters over the next three years.

Meeting Orthodox Christians

Part of my turn to Orthodoxy can be attributed to the people I met. I was fortunate that Gordon-Conwell offered classes on early Christianity. In that class I met Theo, a bright undergraduate from nearby Gordon College who was Greek Orthodox. Theo introduced me to Fr. Chris Foustokos, the priest at Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church in Newburyport. I later had a long conversation with Fr. Chris during which I grilled him on Orthodox theology and practice. I came away impressed that he did in fact have a personal faith in Christ. I was also relieved to learn that he believed that those who converted to Orthodoxy would not have to undergo Hellenization. In my second year, I sat down for dinner and saw the student sitting across from me make the sign of the Cross. It turned out that Paul had just graduated from Holy Cross Orthodox Seminary and was up at Gordon-Conwell to study youth ministry. A number of us Protestants got to know Paul quite well, and later that semester we accompanied him to the Orthodox Good Friday service in Newburyport.

Did these early contacts persuade me to become Orthodox? Not really. At the time, becoming Orthodox was the farthest thing from my mind. Nonetheless, I was curious about Orthodoxy. These friendly encounters encouraged me to a learn more about Orthodoxy and its ancient Faith. So, while not decisive, these early encounters were indispensable to my becoming Orthodox. Looking back, I would say that what was critical were the positive tone and the absence of a judgmental spirit in the Orthodox Christians I met.

Meeting Orthodox Converts

In my third year, I went to the Greek Orthodox church in Newburyport to hear a presentation by Peter Gillquist, a recent Protestant convert to Orthodoxy. I asked him some hard questions about Orthodoxy and Reformed theology. I admired his honesty, but was frustrated when he humbly admitted that he did not know enough about Reformed theology to answer my questions. This left me on my own to work out the answers about how Orthodoxy and Reformed theology relate to each other. In many ways this conversation was the genesis of the OrthodoxBridge blog. Rather than leave people with similar questions to struggle on their own, I decided I would do the research and present my findings on questions relating to Orthodoxy and Protestantism. The results of my research can be found in the Archives section of this blog.

Did the lack of answers affect my turn to Orthodoxy? Yes, because I needed good reasons for making such a radical change. I shared the Reformed tradition’s concern for right doctrine and the careful study of Scripture. My sense of personal integrity was such that I could not undergo intellectual lobotomy and mindlessly accept Orthodox teachings and practices; I needed good answers, preferably biblical reasons, for becoming Orthodox. The complexity of the issues surrounding the Orthodox veneration of icons, and Protestantism’s core doctrines of sola scriptura and sola fide were such that I needed to do extensive research. The answers are there but require thinking outside the Protestant paradigm and questioning the unspoken assumptions that underlie Protestant theology.

I also got to meet Frank Schaeffer, another recent convert, at the Orthodox church in Newburyport. Where Peter Gillquist was more soft spoken in his presentation of Orthodoxy, Frank was very much in-your-face. When I asked whether I had to give up my Reformed theology to become Orthodox, he answered: “Yes, because it’s theologically off the map.” I was taken aback and a bit affronted by his blunt answer. I know that Frank Schaeffer has caused consternation by some of his recent statements, but I do have some positive memories of his kindness. Once a fellow seminarian was struggling with going to church so I suggested he visit a nearby Orthodox church. He met Frank Schaeffer, who then invited him to his home and cooked him lunch! I was envious when my friend told me this story.

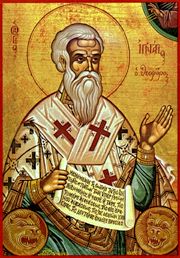

Paper on Icons

During my third year, I wrote a paper on icons and Evangelical spirituality for Prof. Richard Lovelace’s class. For this class I read some of the Orthodox classics like John of Damascus’ Three Treatises on the Divine Images and Theodore the Studite’s On the Holy Images. I also drove down to Holy Cross Greek Orthodox Seminary in Brookline and interviewed Prof. Theodore Stylianopoulos. I was struck by how warm and welcoming Prof. Stylianopoulos was. I was also struck by how restricted access was at the Orthodox seminary library — a big contrast to Gordon-Conwell’s open stacks! One particularly useful book I came across was Antony Ugolnik’s The Illuminating Icon. From this book I learned how images can shape one’s internal life and how Orthodox icons helped preserve Orthodoxy during the decades of oppressive Communist rule in the Soviet Union. This book made me keenly aware of how modern American consumerism is suffused with icons (images). The striking visuals of modern advertising that promote materialism are the spiritual opposite of Orthodox icons. Protestantism’s iconoclasm has made it vulnerable to the iconography of Madison Avenue and Hollywood. From the mass media we are inundated with images of beautiful people with “perfect” bodies who have it all and live “perfectly happy” lives (God removed from the picture). Much of modern advertising speaks to our bodily appetites e.g., food or comfort, or speaks to our inner vanity or selfish desire to do “our own thing.” What is being promoted is a secular worldview where God is allowed a limited role in the modern American lifestyle. In contrast, the otherworldly quality of Orthodox icons points us to the eternal reality that lies beyond the evanescent fads of modernity and our accountability before the judgment seat of Christ.

My paper argued that the aesthetic qualities of icons can be beneficial for personal devotions and that the visual nature of icons can supplement Protestantism’s emphasis on the printed text. This paper falls short of Orthodoxy’s sacramental understanding of icons, but I am not embarrassed by what I wrote because the gap between Protestantism and Orthodoxy is considerable. It takes a while for a Protestant mindset to “get it” with respect to Orthodoxy. This calls for much patience and understanding on the part of Orthodox Christians when they meet Protestants interested in Orthodoxy.

Orthodox Books

Much of my turn to Orthodoxy at Gordon-Conwell came through reading. Two occasions stand out vividly. During my first year, I went to downtown Boston to make travel arrangements to fly back home. It was a cold and dark winter afternoon, and as I stood in line reading Alexander Schmemann’s For the Life of the World. I found my secular worldview shattered. In the opening chapter, I encountered Orthodoxy’s sacramental understanding of creation and how the common, ordinary meal was a foreshadowing of the Eucharist. What I encountered was not just the idea of sacramental reality, but also Orthodoxy as a gateway into that reality. While Protestantism affirms the reality of heaven, it tends for the most part to project heaven into the distant future or into the afterlife. This way of thinking leaves the present life encased in a secular materialism. I learned that in Orthodoxy ordinary stuff like water, bread, wine, and oil can become vessels of divine grace, ushering us into the kingdom of God here and now.

Much of my turn to Orthodoxy at Gordon-Conwell came through reading. Two occasions stand out vividly. During my first year, I went to downtown Boston to make travel arrangements to fly back home. It was a cold and dark winter afternoon, and as I stood in line reading Alexander Schmemann’s For the Life of the World. I found my secular worldview shattered. In the opening chapter, I encountered Orthodoxy’s sacramental understanding of creation and how the common, ordinary meal was a foreshadowing of the Eucharist. What I encountered was not just the idea of sacramental reality, but also Orthodoxy as a gateway into that reality. While Protestantism affirms the reality of heaven, it tends for the most part to project heaven into the distant future or into the afterlife. This way of thinking leaves the present life encased in a secular materialism. I learned that in Orthodoxy ordinary stuff like water, bread, wine, and oil can become vessels of divine grace, ushering us into the kingdom of God here and now.

Magnolia rocky shore — Katie Young

During my third year I would often spend my mornings reading while sitting against a large rock on Magnolia’s rocky shore. One of the books I read was Kallistos Ware’s The Orthodox Way. The chapter “God as Mystery” gave me a glimpse of Orthodoxy’s apophatic approach of understanding God through prayer. During this time I was writing my statement of faith paper for Prof. John Jefferson Davis’ class. This assignment was very much in keeping with Western Christianity’s cataphatic methodology, in which one seeks to learn facts about God and then express this understanding of God through words. From The Orthodox Way I learned how in the apophatic approach, intellectual study and prayer can be integrated to advance our knowing God.

During my third year I would often spend my mornings reading while sitting against a large rock on Magnolia’s rocky shore. One of the books I read was Kallistos Ware’s The Orthodox Way. The chapter “God as Mystery” gave me a glimpse of Orthodoxy’s apophatic approach of understanding God through prayer. During this time I was writing my statement of faith paper for Prof. John Jefferson Davis’ class. This assignment was very much in keeping with Western Christianity’s cataphatic methodology, in which one seeks to learn facts about God and then express this understanding of God through words. From The Orthodox Way I learned how in the apophatic approach, intellectual study and prayer can be integrated to advance our knowing God.

The Liturgy

During my time at Gordon-Conwell, I attended a few Orthodox liturgies. One might expect that I fell head over heels in love with the Divine Liturgy, but that was not the case. The language barrier was so daunting that I saw Greek Orthodox worship as an obscure, intricate ritual. It was frustrating. My experience was like that of a hungry person drawn to a restaurant but standing with his face against the window, looking on longingly, but unable to taste the delicacies within. It was not until I began to attend an all-English Liturgy at a Bulgarian Orthodox parish in Berkeley, California, that my journey to Orthodoxy began in earnest. Attending the Liturgy there week after week, being immersed in the flow of hymns and prayers, helped me to understand what Orthodoxy is about and experience God as Mystery.

Magnolia village, MA source

Looking Back

My time on Massachusetts’ North Shore was but a small part of my journey to Orthodoxy. By the end of my three years there I was still very much a Protestant in my thinking, but the various personal encounters and books that I read had had an impact on me. They were like little seeds planted in the ground, invisible under the surface but slowly germinating, and in due time emerging as a plant that would one day become a pleasing fruit-bearing tree. An equally good analogy used by my compatriot David Rockett here at the OrthodoxBridge is that these early encounters were like boulders assaulting my medieval castle walls without my noticing the small cracks they were creating in my theological and spiritual foundation! Analogies aside, one take-away here is that journeys to Orthodoxy are rarely instant, dramatic flashes of light in the sky, but more like the gradual light of dawn in which many little things long hidden become noticeable and show their results much later, sometimes after several years.

Robert Arakaki

Recent Comments