Today’s posting is by Stefan Pavićević. Welcome Stefan!

Today’s posting is by Stefan Pavićević. Welcome Stefan!

Stefan Pavićević was born and raised in the city of Bitola, the Republic of Macedonia (aka FYROM). He is currently studying engineering and computer science at St. Clement of Ohrid University of Bitola. He attends the Most Holy Theotokos Orthodox Church (Црквата Света Богородица).

I was raised in a nominal Eastern Orthodox family. Even though I was never taught about the Christian faith, I always had some sense of the supernatural, that which is beyond natural. I always believed in God, even though I didn’t know anything about Him. Yet I remember desiring to pray regarding my needs and desires but I always felt I won’t be heard, because I was not baptized. I don’t know why my parents had forgotten to baptize me as an infant. Maybe it wasn’t something of a great importance to them; maybe they wanted to raise me an atheist; maybe it was simply that they weren’t able to.

My life has been a constant search for truth. Since earliest childhood I’ve always wanted to know: “What is the meaning of life?” and “Why there is death?” I was never satisfied with shallow answers like: “The meaning of life is to study, work, have a family, etc.” They never made any sense to me. And they still don’t. If that were the meaning of life, then life doesn’t have much meaning, honestly.

In the course of my life I have changed so many religious and philosophical beliefs and positions, that to many it would seem like there is no constancy and stability in my life. And to be honest, I think they would be right. Yet, pretending that wasn’t the truth, would do more hurt than profit.

My childhood was not an easy one. I was bullied, laughed at, most of the time I was lonely. I had to struggle with the consequences of constantly being and feeling rejected. Maybe that’s what made me search for deeper meaning in life. Maybe that’s what finally made me turn my back on God and become involved in paganism and occultism, thinking that’s where I would find deeper meaning I often longed for.

I came close to calling myself an atheist, then I experienced some good in life. I experienced what it is like to be accepted. Initially I had no plans of becoming a Christian. Something happened that paved the way or opened my heart to Christianity. I had started high school and even though I was very opposed to the idea of reading the Bible (since we were studying ancient literature at that time), it somehow fell into my hands and I started reading it. Shortly afterwards, I felt a strong conviction about its truthfulness that I simply became a Christian. I was baptized in the Orthodox Church, and all was going to be fine. And then I discovered Protestantism.

Who is correct, actually?

Though I never thought I would become a Protestant, I must admit I was not content with being Eastern Orthodox at that time. This was probably because I thought I was familiar enough with it, and I thought it was uninteresting for me. I thought I should explore other options such as Catholicism and eventually Protestantism, even though it was never my intention to become a Protestant. Catholicism was a viable alternative though. Then I stumbled upon actual Protestants, started attending Protestant services, and eventually ditched Orthodoxy because it seemed unbiblical to me. Yet once I was Protestant the existence of the variety of denominations troubled me. It went strongly against my search for truth. It was antithetical to my quest for truth. What was I to do, presented with competing truth claims? To accept all of them as true would be relativism, rendering all truth as relative and therefore unimportant, something unthinkable for a Christian, because it goes against Christ Himself Who claims to be Truth. [Note 1; see References at bottom]

I started out as a general Protestant with no denominational belonging, but soon I realized I must find the true doctrine and join a denomination which teaches it. So, I became a Baptist, because I thought baptism is an outward sign of an inward reality for those adults who profess faith in Christ. Then I went even further when I became an IFB (Independent Fundamentalist Baptist) which is some of the worst Christian manipulative cults. Finally, the unthinkable happened. I became a Calvinist because I became convinced the Bible taught the so called doctrines of grace (or TULIP) which deny the freedom of the will and teach we’re unconditionally elected and preserved by God solely because of His [arbitrary] decree of election. And shortly after that, I found many problems with Calvinism because not only does the Bible speak that one can fall away from the faith, but it is clear that Christ died for all of mankind, not just the elect, as Calvinism holds. And these were not the only problems I had with Calvinism. I had philosophical problems as well. Finally, I became a Lutheran. Now I started experiencing some true joy and freedom, and finally turned a new page in my Christian life. The anxiety and depression I experienced previously — and I struggled with depression quite a lot — was finally gone for good. As a Lutheran, I finally accepted infant baptism, baptismal regeneration, the real presence in the Eucharist, etc. I was now comfortable with claiming Tradition as my own (for a brief defense of Holy Tradition, I would recommend this text I recently wrote).

But one thing that always troubled me as a Protestant was, who is correct? What is the truth? I’ve seen Calvinists and Baptists argue, and I’ve seen Lutherans and Calvinists argue. All of them had real, strong arguments for what they believed. How was I to decide who is right? By reading the Bible? [Note 2] Well, I could see how the Bible supported either position, given a particular point of view. Who was more biblical? There was no way of knowing; both were and both weren’t.

Holy Tradition and the Holy Scriptures

Holy Tradition and the Holy Scriptures

As a Lutheran, I was finally bold to quote Tradition in my favor. Look, I said, the early Church believed in infant baptism, baptismal regeneration, the real presence. I was not afraid to say this, because I believed it was the Scriptures that ultimately taught these things and the Tradition simply witnessed to it. But whenever I quoted Holy Tradition to support my views, I always felt hypocritical about it. How is it that I can use Tradition for those things when the very same Tradition [Note 3] stands against my belief in Sola Scriptura and Sola Fide? Many Protestants conceded that no church father taught Sola Fide. The only justification I had was that if Tradition teaches something contrary to the Bible, that particular facet of Tradition is to be rejected. What I didn’t realize at that time was that I was setting up my interpretation of the Bible against that of those I disagreed with. I eventually realized it is not as if the Church Fathers weren’t familiar with the Scriptures, but simply that I thought they were wrong. And this is why I couldn’t remain a Protestant in a good conscience. If the Church Fathers got Christianity and the Holy Scriptures wrong, why think I or anybody else got it better? If they erred on so important things, why think they were right about anything at all? If they didn’t have the true gospel, how could I possibly call them Christians or trust them at all? And if they have been so wrong, Christ didn’t fulfill His promise that He would send the Holy Spirit Who would guide the Christians into all truth [Note 4]; and the gates of Hell finally prevailed against the Church [Note 5], until Luther came.

The Problem of Truth

Finally, I encountered the claims of the Eastern Orthodox Church. And I, for once in my life, was (or rather willingly became) vulnerable to Orthodoxy. I just gave up all the fear I’ve had of Eastern Orthodoxy during my Protestant years. And I started reading EO apologetics and arguments online and found myself in agreement with them. It soon became very clear I was headed East. I’ve read hundreds of articles, arguments and conversion stories online. I was also able to afford some books which have also been of immense help. Meanwhile, I started attending Orthodox services and started immersing myself in the Orthodox way of life, because my Orthodox friends would often tell me how Orthodoxy is more than just a set of beliefs, but a way of life.

And then I found myself in trouble again. On what grounds should I accept the Ecumenical Councils? Or rather, how did the Church accept them? What made a council ecumenical? Also, what if two Orthodox Christians essentially disagreed on certain things? I came to Orthodoxy seeking for doctrinal unity and one-mindedness. And then I discovered that finding doctrinal truth is far more complicated than most of us would admit. If it weren’t so, there wouldn’t be so much diversity and disagreement. Another thing to note is that I also discovered that some things are dogma (absolutely essential) and there were many things that weren’t absolute dogma and that many people held different opinions. So, I came to the realization that dogmatizing what is not a dogma is also dangerous. To elevate a particular opinion over many others just as viable and tenable is evidently problematic, and can also lead to a schism. And that’s what Protestants did and still do, hence the existence of so many denominations. I also found out that the church fathers could be proof-texted and misinterpreted as easily as the Scriptures. What is one to do? How can I know the truth?

However, what I soon came to understand is that the Church does not have any problems with Her teaching at all. The real problem is that I still thought as a Protestant, that truth (and orthodoxy) is just a set of doctrinal propositions and heresy is anything contrary to that. While at the surface level it may seem like that is the case, this is not the Orthodox understanding of truth. [Notes 6, 7, 8, 9]

Before moving on, let me briefly explain a few very important concepts Eastern theology holds dear.

Apophatic (negative) theology, as opposed to cataphatic (positive) theology, is also known as theological knowledge obtained by negation. It does not say anything about Who or what God actually is (as in cataphatic theology), but rather admits ignorance and only speaks of what God is not. This is because we’re unable to know God as He is in His essence, because He is unlike anything else. We can’t say God exists because existence is characteristic of created things. God is beyond existence. He is called Creator by the virtue that He is uncreated. Yet, there is a way we can know Him, and that is by His energies, or what is more commonly known as His attributes. Thus, another important concept is the Essence-Energies distinction. The energies are fully and truly God, yet they are distinct from His essence. The energies belong to His essence and proceed from His essence as rays proceed from the sun.

All of theology, therefore, is apophatic, because we can’t know God in His essence. We can’t study Him and make positive statements about Him. We can only experience Him in His energies, i.e. His grace in the communal life of the Church, through prayer, ascetic struggle, partaking in the Eucharist and the rest of the Divine Sacraments. This is also known as theosis (lit. deification) which means we become partakers of the divine life by being united to God by His grace, through His Church.

Evagrius of Pontus wrote: “God cannot be grasped by the mind. If He could be grasped, He would not be God.” A theological scholar could write a lengthy book about God but still fall woefully short of the reality of God. To think that we can adequately capture who God is in a book is idolatry. This is why cataphatic theology inevitably comes up short. In Orthodoxy a theologian is not so much someone who has done much studying about God but someone who has had an encounter with God. We need to remember that beyond the text of the Ten Commandments (cataphatic theology) was the mystery of God Moses encountered when he went up Mount Sinai, entered into the thick cloud and in the darkness of the cloud encountered God in holy mystery (apophatic theology) and came down with his face radiant (theosis). (See Exodus chapters 19, 20, and 34:29-35)

Dogma, then, is not about making positive statements about God, but is rather a limited, apophatic confession of the Mystery which has as its goal to protect the Mystery and discern heresy. Similarly, heresy is not merely something opposite to a particular set of doctrines, but something which destroys the Mystery and renders Theosis impossible. This, it does by rationalizing certain aspects of the Mystery; overemphasizing one aspect over the others; philosophizing and attempting to make positive statements where such are impossible.

Truth is a Person

With all that in mind, let me suggest a fresh perspective, a fresh paradigm, which says that Truth is a Person. [Note 10] Namely, Christ, the Divine Logos, the second person of the Holy Trinity. And this I mean quite literally and apophatically. Christ is ultimately the beginning, the middle, and the end of truth. He is the presupposition, the method and the conclusion.

Let us approach the Mystery of the Incarnation and of the Holy Trinity with a renewed sense of wonder, and childlike trust in the Mystery of our Faith. Let us prayerfully contemplate this Mystery and constantly be reminded of God’s love for His creation.

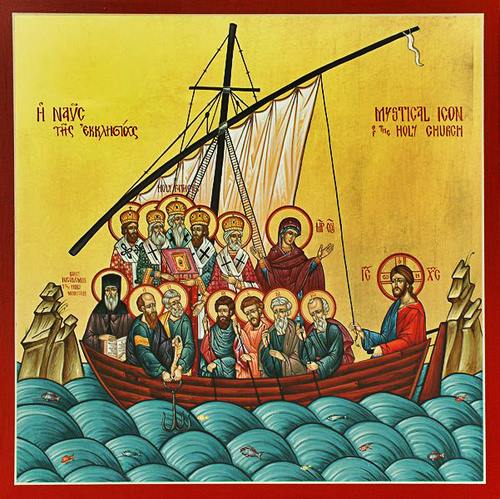

And let those who desire to find Christ, put their trust and faith in the Church He established and preserved throughout the ages, even as He promised to do.

To hear Jesus, and not just his words, we have to stand within the tradition of the Church; we have to put our trust in those to whom our Lord entrusted his mission, his sending. Part of the stillness that is needed for us to hear the words of Jesus is a sense of presence, and it is this that tradition conveys. We become Christians by becoming members of the Church, by trusting our forefathers in the faith. If we cannot trust the Church to have understood Jesus, then we have lost Jesus: and the resources of modern scholarship will not help us to find him. – Fr. Andrew Louth

I do not want my readers to come to the conclusion that I’m wholly opposed to academic study and inquiry of history or theology, but I want to state that I believe that even the Church is an article of faith. We trust the Church just as we trust a teacher to teach us the truth or a doctor to bring healing to our bodies. If we have no desire to put our faith in Her, then no study and scholarship will be able to help us. However, academic study is not antithetical or opposed to what the Church teaches, and can prove itself useful in many ways, and for that reason shouldn’t be repudiated.

What is important is that we always give the highest priority to the corporate, sacramental, liturgical, prayerful, communal and mystical life of the Church, where we directly experience our union with God and from which every orthodox teaching has its source. I also want to make it clear that I do not believe in any sort of theological relativism; however, scientific study is incapable of delivering theological truth.

“If you are a theologian, you will pray truly. And if you pray truly, you are a theologian.” – Evagrius of Pontus

Some Concluding Remarks

Finally, I want to say a few words why I chose Orthodoxy and why I believe the Orthodox Church to be the One Church that our Lord Himself established.

First, the Eastern Orthodox Church (along with the Roman Catholic Church) can claim apostolic succession, unlike Protestant churches, which unfortunately, cannot make the case for that. The filioque and the papacy, however, seem to me to be what caused a breach in Church unity, since it was the Roman Church along with Her Pope that went rebelled against the authority of the Ecumenical Councils, and thus changed the ecclesiology of the Roman Church. Rome, once part of the conciliar Church, declared Herself the Universal Church, ceasing to be part of the conciliar Church.

Many people think they are criticizing Orthodoxy but what they are really criticizing is their understanding or conception of Orthodoxy. The Republic of Macedonia is a post-communist society. This means that many people were raised and indoctrinated in its atheistic ideology. Many people in my town are nominal Orthodox. Because they have not been properly catechized they do not understand what Orthodoxy is about and leave the Church. When Protestants criticize Eastern Orthodoxy they are often criticizing either strawmen or nominal Orthodoxy.

And last, but not least, what has drawn me to Orthodoxy is the beauty of the Orthodox Church. A friend on Facebook recently just posted how one of the underrated and underused argument for the existence of God is beauty. And I absolutely agree with that. There is always a very direct and essential connection between truth and the beautiful; what is good and true is beautiful.

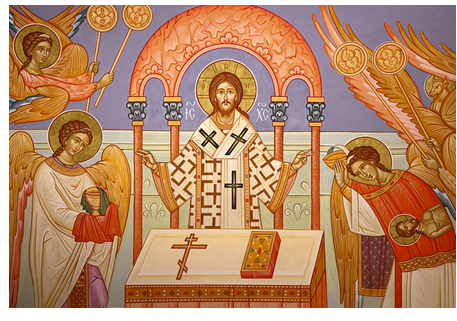

Beauty is an important part of our lives, and J.R.R. Tolkien was definitely aware of this. His works reflect the importance of beauty. Unfortunately, modern man has forgotten about beauty altogether. So much so that modern works both fiction and non-fiction are devoid of beauty. The same is sadly true in much of contemporary Christian theology. This probably has its roots in Reformation thought as a whole and Calvin’s iconoclasm in particular. The physical reality of our faith was de-emphasized. Churches gradually became empty buildings with only pews and the pulpit. This, I believe, is a mere reflection of the abandoned spiritual beauty. The de-emphasis of beauty in theology resulted with the de-emphasis of beauty in worship, and ultimately in all of human culture. Reading Tolkien has helped me to appreciate the spiritual importance of beauty. His description of beautiful places like the Shire, Lothlorien, and Rivendell has opened my mind and heart to the spiritual beauty of the kingdom of God. In the Orthodox Church I found that truth is beautiful. There is a passage that describes the elves singing songs in the Hall of Fire in Rivendell that reminds me of the Liturgy. The Divine Liturgy is heaven on earth.

At first the beauty of the melodies and of the interwoven words in elven-tongues, even though he understood them little, held him in a spell, as soon as he began to attend to them. Almost it seemed that the words took shape, and visions of far lands and bright things that he had never yet imagined opened out before him; and the firelit hall became like a golden mist above seas of foam that sighed upon the margins of the world. Then the enchantment became more and more dreamlike, until he felt that an endless river of swelling gold and silver was flowing over him, too multitudinous for its pattern to be comprehended; it became part of the throbbing air about him, and it drenched and drowned him.

No, I’m not merely speaking of outward beauty (though that is not without its importance), but rather of the spiritual beauty Orthodoxy possesses. Orthodoxy is organic, holistic and therapeutic – it is meant to heal and restore the whole person. It is personal though not individualistic. Beyond that there is the Holy presence of God, that is able to instill proper reverence and fear of God in the heart of anyone who sincerely approaches God. And the whole spiritual experience, hard as it may be, is filled with joy and spiritual peace.

No, I’m not merely speaking of outward beauty (though that is not without its importance), but rather of the spiritual beauty Orthodoxy possesses. Orthodoxy is organic, holistic and therapeutic – it is meant to heal and restore the whole person. It is personal though not individualistic. Beyond that there is the Holy presence of God, that is able to instill proper reverence and fear of God in the heart of anyone who sincerely approaches God. And the whole spiritual experience, hard as it may be, is filled with joy and spiritual peace.

Similarly, if someone asks me why I’m a Christian, I would say that it is the only thing in the world that can satisfy my deepest needs, both aesthetically, morally, theologically, philosophically and existentially. It is the only thing worth living for!

References

Note 1

Jesus said to him, “I am the way, and the truth, and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me. If you had known me, you would have known my Father also. From now on you do know him and have seen him.” – John 14:6,7 ESV

Note 2

So Philip ran to him and heard him reading Isaiah the prophet and asked, “Do you understand what you are reading?” And he said, “How can I, unless someone guides me?” And he invited Philip to come up and sit with him. – Acts 8:30,31 ESV

Note 3

So then, brothers, stand firm and hold to the traditions that you were taught by us, either by our spoken word or by our letter. – 2 Thessalonians 2:15 ESV

Note 4

When the Spirit of truth comes, he will guide you into all the truth, for he will not speak on his own authority, but whatever he hears he will speak, and he will declare to you the things that are to come. – John 16:13 ESV

Note 5

And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it. – Matthew 16:18 ESV

Note 6

[I]f I delay, you may know how one ought to behave in the household of God, which is the church of the living God, a pillar and buttress of the truth. – 1 Timothy 3:15 ESV

Note 7

As I have already observed, the Church, having received this preaching and this faith, although scattered throughout the whole world, yet, as if occupying but one house, carefully preserves it. She also believes these points [of doctrine] just as if she had but one soul, and one and the same heart, and she proclaims them, and teaches them, and hands them down, with perfect harmony, as if she possessed only one mouth. For, although the languages of the world are dissimilar, yet the import of the tradition is one and the same. For the Churches which have been planted in Germany do not believe or hand down anything different, nor do those in Spain, nor those in Gaul, nor those in the East, nor those in Egypt, nor those in Libya, nor those which have been established in the central regions of the world. But as the sun, that creature of God, is one and the same throughout the whole world, so also the preaching of the truth shines everywhere, and enlightens all men that are willing to come to a knowledge of the truth. Nor will any one of the rulers in the Churches, however highly gifted he may be in point of eloquence, teach doctrines different from these (for no one is greater than the Master [the Church]); nor, on the other hand, will he who is deficient in power of expression inflict injury on the tradition. For the faith being ever one and the same, neither does one who is able at great length to discourse regarding it, make any addition to it, nor does one, who can say but little diminish it. – St. Irenaeus, Against All Heresies

Note 8

For as we ceased to seek for truth (notwithstanding the professions of many among Greeks and Barbarians to make it known) among all who claimed it for erroneous opinions, after we had come to believe that Christ was the Son of God, and were persuaded that we must learn it from Himself; so, seeing there are many who think they hold the opinions of Christ, and yet some of these think differently from their predecessors, yet as the teaching of the Church, transmitted in orderly succession from the apostles, and remaining in the Churches to the present day, is still preserved, that alone is to be accepted as truth which differs in no respect from ecclesiastical and apostolical tradition. – Origen, On First Principles

Note 9

In reference, however, to the character of Novatian, dearest brother, of whom you desired that intelligence should be written you what heresy he had introduced; know that, in the first place, we ought not even to be inquisitive as to what he teaches, so long as he teaches out of the pale of unity. Whoever he may be, and whatever he may be, he who is not in the Church of Christ is not a Christian. Although he may boast himself, and announce his philosophy or eloquence with lofty words, yet he who has not maintained brotherly love or ecclesiastical unity has lost even what he previously had been… But apostates and deserters, or adversaries and enemies, and those who lay waste the Church of Christ, cannot, even if outside the Church they have been slain for His name, according to the apostle, be admitted to the peace of the Church, since they have neither kept the unity of the spirit nor of the Church. – St. Cyprian

Note 10

“For years in my studies I was satisfied with being ‘above all traditions’ but somehow faithful to them… When I visited an Orthodox Church, it was only in order to view another ‘tradition’. However, when I entered an Orthodox Church for the first time (a Russian Church in San Francisco) something happened to me that I had not experienced in any Buddhist or other Eastern temple; something in my heart said this was ‘home,’ that all my search was over. I didn’t really know what this meant, because the service was quite strange to me and in a foreign language. I began to attend Orthodox services more frequently, gradually learning its language and customs… With my exposure to orthodoxy and Orthodox people, a new idea began to enter my awareness: that Truth was not just an abstract idea, sought and known by the mind, but was something personal–even a Person–sought and loved by the heart. And that is how I met Christ.” – Fr. Seraphim Rose

Recent Comments