Pastor Steven Wedgeworth — Trinity Talk No. 1 (2 November 2009)

Trinity Talk, an Internet radio blog, did a three part series with Pastor Steven Wedgeworth on the Eastern Orthodox Church. The interviews took place on November 2, 16, and 30, 2009. Trinity Talk is a creedal podcast by Uri Brito and Jarrod Richey. Wedgeworth is interim pastor of Immanuel Presbyterian Church (CREC) in Clinton, Mississippi.

First time listeners should be prepared to listen a short commercial then to a fairly lengthy introduction about Trinity Talk before actually hearing Wedgeworth at

5:07. Although presented as interviews, what one hears are a series of questions that leads Pastor Wedgeworth into various topics. This is not a criticism, but more of a heads up alerting the listener to expect something more of a monologue than the dynamic give-and-take of a real conversation.

In this blog posting I will be responding to Pastor Wedgeworth’s November 2 presentation. This review will be structured along the lines of topics than chronology. To facilitate the review I will be referencing his statements by minute and second in the pod cast.

What is the Eastern Orthodox Church?

Pastor Wedgeworth defined Eastern Orthodoxy in terms of institutional structure and political authority. However, he failed to draw attention to the role of Holy Tradition. Wedgeworth’s omission of this fact results in a distorted understanding of Orthodoxy. The bishop’s authority rests upon his holding the Apostolic Tradition. If he were to abandon the Apostolic Tradition or tamper with it, he loses his ecclesiastical authority no matter the correctness of his episcopal ordination. This would be like a Protestant pastor upholding the Bible alone, but denying salvation by grace through Christ.

Wedgeworth’s discussion of the five patriarchates gave too much attention to the influence of the Roman Empire. One almost gets the sense that the Roman Empire incorporated the Christian church into its apparatus. Wedgeworth asserted that soon after Constantine converted to Christianity it did not take long for the church to be ordered along “imperial lines.” He went on to say that these five patriarchal cities were “chosen” (8:39) because it was “politically advantageous” (8:49). It would be more accurate to say that Emperor Constantine recognized the inevitable in the Edict of Milan after the Decian persecutions proved to be too costly and disruptive to the stability of the Roman Empire. Furthermore, the recognition of the five patriarchates did not stem from Emperor Constantine, but the Ecumenical Councils (see Canon 3 of the Council of Constantinople [AD 381] and Canon 28 of the Council of Chalcedon [AD 451]).

Another omission is the conciliar nature of the early church. The early church often settled theological controversy through conciliar action, i.e., the bishops would come together and as a council uphold Holy Tradition. The Ecumenical Councils were regarded as having a higher authority than individual bishops and patriarchs.

Pastor Wedgeworth omitted the Orthodox Church as an Eucharistic community. This can be summed up by Roman Catholic theologian Henri de Lubac’s statement: “The Church makes the Eucharist and the Eucharist makes the Church.” This pithy statement is one that an Eastern Orthodox Christian can agree with wholeheartedly. The Eucharist sums up and ties together the Christian Faith. One could say that alongside apostolic succession through the bishops is liturgical succession through the Sunday Liturgy. For two thousand years the Orthodox Church has been celebrating the Liturgy without break Sunday after Sunday. Thus, an Orthodox Christian today is part of a liturgical tradition that takes him back to time of Athanasius the Great, Irenaeus of Lyons, and Ignatius of Antioch, and beyond that to the original Last Supper. Protestants lack this liturgical continuity having instead a ceremony based upon their reading of the Gospels. They lost this liturgical continuity when they broke off from Rome.

What makes one Orthodox?

Wedgeworth does a good job of succinctly defining an Orthodox Christian as one under an Orthodox bishop (17:50). If I ever have doubts about someone claiming to be Orthodox I ask two questions: (1) Who is your bishop? and (2) Is he in communion with the Patriarch of Constantinople?

However, Wedgeworth gives an imbalanced picture by approaching Orthodoxy principally as “authority structure” (17:37). In contrast the church as “authority structure,” Bishop Kallistos Ware defined the Orthodox Church as communion. In The Inner Kingdom Ware cited Lev Gillet:

An Orthodox Christian is one who accepts the Apostolic Tradition and who lives in communion with the bishops who are the appointed teachers of this Tradition. (page 14; italics in original)

Where Western Christianity and Protestantism put a premium on faith as intellectual understanding, Eastern Orthodoxy places more emphasis on relationship and communion. To receive Communion in the Orthodox Church means that one accepts Apostolic Tradition, e.g., the Ecumenical Councils, the Liturgy, the Nicene Creed, the icons, Mary as the Theotokos etc. It also means that one accepts the bishop as the recipient and guardian of Apostolic Tradition. Both the bishop and the laity are bound by Apostolic Tradition. The bishop has authority in the church so long as he upholds Tradition, but if he attempts to modify Tradition he loses that authority. This is a subtle nuance that Pastor Wedgeworth failed to convey in his interview.

Filioque Clause — “And the Son”

The Filioque clause was a major issue that contributed to the Great Schism of 1054 between Eastern Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism. While the insertion of the phrase “and the Son” into the third section of the Nicene Creed about the Holy Spirit: “Who proceeds from the Father (and the Son)” may seem like a tempest in a teacup for some, for the Eastern Orthodox this is a major concern.

Pastor Wedgeworth seems to be unaware of the role of conciliarity in the early church. Early pre-Schism popes were theologically and ecclesiastically Orthodox. They resisted attempts to amend the Nicene Creed. The autarchic papacy independent of the Ecumenical Councils and other patriarchates represents a break from the theological method of the early church. The Orthodox Church’s refusal to alter the Nicene Creed is a sign of its continuity with the early church. The decision to unilaterally revise the Nicene Creed through the insertion of the Filioque clause implied the Pope’s belief that he held an authority equal to or higher than the Ecumenical Councils. Protestantism’s cavalier attitude to the Filioque controversy reflects its operating on an all together different theological principle — sola scriptura.

Wedgeworth statement that he does not see it as a “church dividing issue” (12:58) makes sense in light of his abstract and ahistorical approach to doing theology. This theological method has roots in medieval Scholasticism which saw theology in terms of propositions and syllogisms logically organized, and the Humanist movement which saw theology in terms of an critical, scientific reading of the biblical text. This blind spot in Wedgeworth is all too common among Protestants and shows much they have been shaped by the Western theological method. So while Wedgeworth displays a degree of awareness exceptional among Protestants, until he grasps the Eastern Orthodox approach to theology, e.g., the role of Holy Tradition and conciliarity, he will not be able to adequately describe and address the differences between the Reformed and the Orthodox theological traditions.

Council of Florence (1438-39)

Wedgeworth’s mention of the Council of Florence shows an exceptional awareness of Orthodox history (18:21). But his attributing the repudiation of the Council of Florence to the Patriarchate of Moscow and his statement that the Patriarch of Moscow excommunicated the Patriarch of Constantinople makes me wonder: What has he been reading?? Given that the Orthodox delegates repudiated the agreement soon after they returned home raises question as to whether the Patriarch of Moscow did in fact excommunicate the Patriarch of Constantinople as Wedgeworth claims (18:55). I challenge Pastor Wedgeworth to substantiate his claims.

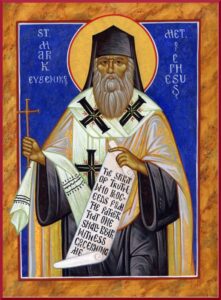

There are two significant omissions in Wedgeworth’s account of the Council of Florence controversy: (1) the role of St. Mark of Ephesus and (2) the role of the monastics and laity in the rejection of the council. The omission is troubling given the fact that Mark of Ephesus was mentioned several times in Kallistos Ware’s The Orthodox Church (see pp. 71, 203, 213) and he is mentioned in other history texts as well. This throws into question Pastor Wedgeworth’s church history research.

The Council of Florence debacle underscored the importance of Tradition in Orthodoxy. It showed that even if Orthodox hierarchs — bishops and patriarchs — were to go astray, the laity will rise up in arms to defend Holy Tradition. This event challenges Wedgeworth’s depiction of Orthodoxy as merely an “authority structure.” If that had been the case, then the Patriarchate of Constantinople would have become a Uniate Church soon after. The Council of Florence controversy underscores the fact that Orthodox polity rests on Apostolic Tradition, not institutional power. The Orthodox will not stand by deferentially if Tradition is compromised but will rise up in defense of the Faith received from the Apostles.

Oriental Churches

Wedgeworth discussed briefly the diverse collections of Oriental churches besides the Eastern Orthodox, e.g., the Copts and Nestorians (19:40). He states that if the Bishop of Constantinople did not recognize you, you are not in the true Church (21:38). Technically Wedgeworth is correct but he is glossing over the complexity of the situation. Those who are not familiar with Orthodoxy may assume that the Patriarch of Constantinople exercises top-down authority over all the Orthodox Churches. This overlooks the principle of autocephalous — self governing — churches. Closer to home, the fact is that the Orthodox Church in America (OCA) actively participates in Orthodox life in America despite Constantinople’s reluctance to recognize it’s autocephaly.

Here in Hawaii when Fr. John, the priest of the Greek Orthodox parish, goes on vacation he often asks Fr. Paul, an OCA priest, to fill in for him. Furthermore, Fr. Paul assists Fr. Anatole at the local Russian Orthodox parish. I also know a Coptic Christian who received Communion at the Greek Orthodox Church. This is based upon the understanding that if there is no local Coptic Church, they can receive Communion at a Greek Orthodox Church with their bishop’s approval.

I find it amusing that Pastor Wedgeworth had to rely on the works of a sixteenth century Protestant theologian, Richard Field (1561-1616), for his understanding of the Oriental Orthodox Churches. I’ve read about the Nestorian and the Monophysite controversies in church history and historical theology. Just as important, I have also interacted with their modern day descendants. I had conversations with the bishop of the local Coptic church and the metropolitan of the local Nestorian church. Let me just say here that the reality is much more complex than what one reads in printed text. Pastor Wedgeworth would do well to spend less time reading books and more time out there meeting with flesh and blood members of these traditions.

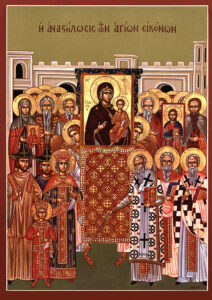

Icons & Reformed Iconoclasm

Pastor Wedgeworth does an able job of comparing religious images in the Eastern Orthodox and the Roman Catholic traditions (23:50). He demonstrates a nuanced understanding by discussing icons not just in terms of their being religious images but also with respect to their liturgical use. The chief difference between the Reformed and Orthodox traditions is not the existence of icons but their use in worship. After giving a brief overview of what icons are and how they are intended to be used in the Orthodox tradition, Wedgeworth presents the Reformed objections to the Eastern Orthodox usage of icons.

Wedgeworth notes that Orthodoxy justifies the use of icons on the Incarnation (27:07). This again shows that he done his homework. He rejects the classic Orthodox defense of icons as not making sense to him (27:51). To defend the Reformed iconoclastic stance Pastor Wedgeworth expounds briefly on Moses’ speech to the Israelites in Deuteronomy 4:15 and the Apostle Paul’s speech at the Areopagus in Athens (Acts 17) (28:25). But Wedgeworth oversimplifies the biblical teachings and skews it in a particular direction. There are two strands of biblical teachings with respect to religious images: (1) the polemic against pagan idolatry and (2) instructions for Old Testament worship which included the use of religious images. Wedgeworth neglected to focus his exegetical skills on Exodus 25 and 26, I Kings 6 and Ezekiel 41. These bible passages describe the liturgical use of icons in Old Testament worship. Pastor Wedgeworth is giving his audience a lop sided and biased understanding of what the Bible teaches.

He asserts that Reformed iconoclasm is consistent with contemporary research on Judaism (31:44). It should be noted that Judaism is a complex religious tradition and equating Protestantism’s iconoclasm with that in Judaism is clearly overreaching. Furthermore, Wedgeworth neglected to bring up the recent archaeological findings at Dura Europos that indicate the use of religious images in first-second century synagogue worship.

If there is a serious flaw in Pastor Wedgeworth’s discussion of the Orthodox position on icon, it is his failure to discuss the Seventh Ecumenical Council and the principle of conciliarity. His citing John of Damascus apologia points to a Western way of doing theology: (1) read a theologian, (2) identify a key theological proposition, then (3) critique the proposition on the basis of logic. Wedgeworth’s reliance on abstract theological reasoning based on his reading of biblical and theological texts is at odds with the Eastern Orthodox theological method. Eastern Orthodoxy does not eschew theological reasoning; rather it situates it within Holy Tradition and within the ecclesial context of the Church. There was controversy over the use of icons in Christian worship but that was settled at the Seventh Ecumenical Council. It was at this Council that unity was restored to the Church. Pastor Wedgeworth may claim that allowing for icons (26:40) is “asking for trouble,” but the fact remains that the early church were in agreement in accepting icons and repudiated iconoclasm. What Pastor Wedgeworth has done is declare his independence from the Ecumenical Councils and endorsed an ahistoric doctrine that has no basis in the historic Christian Faith.

“Icon” of Pastor Rick Warren — Saddleback Church

Wedgeworth argues that it is human beings who are the image of God, not flat wooden icons. He cites Calvin’s belief that in light of the fact that people best present the image of God that the Lord’s Supper should be around the table with people looking at other people (33:00). But the fact remains that in most Protestant churches the congregation faces in one direction looking at the minister who is giving the sermon. Ironically, in the case of contemporary worship one finds in mega churches huge jumbotron “icon” of the pastor!

He asserts that Orthodox worship is not focused on the other people in the room but on the icons (32:22). These assertions about Orthodox worship is based upon a superficial understanding of what goes on in the Liturgy. I have found that there is a strong Christ-centered focus in Orthodox worship. The most prominent icons are that of Jesus Christ. Usually Orthodox churches will depict Christ as the unborn Child in Mary’s womb, Christ crucified on the Cross, and Christ the Pantocrator (the All Ruling One). Boredom and distraction is a common problem in churches. When I find myself distracted, I look at the icons and am reminded of their zeal for Christ. But most time my focus is on the icon of Christ up in the front and the prayers of the Liturgy. I found it harder to focus when I was a Protestant in churches with four bare walls.

Conclusion

It is evident that Pastor Wedgeworth has devoted a fair amount of time and energy into understanding Eastern Orthodoxy. One commendable feature of his presentation of Eastern Orthodoxy is the absence of gross caricature and severe distortion one finds elsewhere. If I have a criticism of Pastor Wedgeworth it is that he sometimes gave an unbalanced portrayal of Orthodoxy and doesn’t quite understand the Orthodox perspective on doing theology, but that is understandable given that he is an outsider trying hard to understand a religious tradition that is so different from his. Overall, he did a commendable job.

It is commendable that Trinity Talk devoted a considerable amount of time to the subject of Eastern Orthodoxy. The podcasts reflect the growing awareness of Eastern Orthodoxy among Reformed Christians and concern over growing numbers of Protestants converting to Orthodoxy. Wedgeworth has referred to this as “conversion sickness.” It seems that Pastor Wedgeworth is attempting to inoculate his listeners by exposing them to an attenuated form of Orthodoxy in his pod cast. I admire his efforts to persuade them to remain in the Protestant fold. The Orthodox response is: Come and see! Come to our Sunday Liturgy. Come and experience the ancient historic worship. Instead of reading books about Orthodoxy or listening to a second hand source on an Internet pod cast, come and talk with real flesh-and-blood Orthodox Christians. Let’s get together and talk, and get to know each other.

Robert Arakaki

Recent Comments