In recent years there has been a growing interest among Evangelicals and Reformed Christians in Eastern Orthodoxy. However, one of the major stumbling blocks for many is the use of icons in Orthodox worship. The use of icons seems to violate the injunction against graven images found in the Ten Commandments. Moreover, there seems to be a dearth of biblical texts pointing to the use of icons in the New Testament. For Evangelicals and Reformed Christians the bottom line question will be: Is there a biblical basis for icons? In this posting I will attempt to forge a basis for a common understanding between Protestants and Orthodox on what the Bible teaches about the role of images in worship and theology.

Regulative vs. Normative Principle

If there is anything that stands out as the hallmark of Evangelicalism and Reformed Christians, it would be their high regard for the authority of Scripture. But whenever one talks about the authority of Scripture, one must also talk about how one interprets Scripture. Within Protestantism there are two major hermeneutical frameworks: (1) what Scripture does not enjoin explicitly is prohibited — the regulative principle of worship, or (2) what Scripture does not prohibit is permitted — the normative principle of worship.

If one follows the regulative principle, then almost immediately we can close the book on the question. Although the word eikon “εικων” can be found in the New Testament it would be a stretch to claim that it refers to the pictorial representations found in Orthodox churches. If on the other hand one were to follow the normative principle then the possibility opens up for an Evangelical or Reformed Christian to find a biblical basis for icons. For the regulative principle to be valid, it must be shown that this particular approach is the normative hermeneutical framework for all Christians. Historically, the regulative principle is characteristic of the Reformed, Anabaptist, Baptist, and Restorationist churches. The normative principle is followed by the Anglican, Lutheran, and Methodist traditions. In other words the regulative approach is not characteristic of Protestantism as a whole, but of certain segments.

There are problems with Reformed churches insistence on the regulative principle. One problem with the regulative principle is that it hasn’t always been followed consistently. Many early Calvinists eschewed musical instruments in worship and advocated psalmody exclusively. However, since the 1800s most of the Reformed churches relaxed their adherence to the regulative principle and allowed for musical instruments. Another problem is the inconsistency in the Reformed understanding of sola scriptura which allows for extra-biblical tradition and their adherence to the regulative principle of worship which rigorously excludes extra-biblical tradition. The regulative principle bears a striking resemblance to what Keith Mahison labels: solo scriptura. This inconsistency in the Reformed theological system creates an opportunity for Reformed Christians to rethink their long-standing iconoclasm.

For a long time I knew that although there were references to “images” in the Bible, these did not refer to Orthodox usage of icons. Then one day I noticed that one dominant feature of Orthodox icons was the depicting of faces: of Christ, of Mary, of the saints and the angels. When I became aware of this fact and put it together with the fact that in the Bible there are numerous references to “face” I realized that here was a way of establishing a biblical basis for the use of icons.

The word “face” is used in the Hebrew Old Testament to denote God’s personal presence. The Old Testament uses several words for face: panim, aph, ayin, anpin. Of these four words, panim is the most frequently used. The Greek New Testament uses prosopon “προσοπον” in most cases with the exception of one verse which uses opsis “οψις.” Although the focus of this paper is on how the biblical writers used the word “face” to denote the divine presence, this is not to deny other ways in which the word “face” has been used in the Bible. The word “face” has other usage such as the earth’s surface — “the face of the earth,” or direction — “set his face towards,” or opposition — “set his face against,” or as an expression of worship — “fell on his face.”

Problems With the New International Version

One surprise in my research has been the issue of Bible translation. I use the New International Version (NIV) because of its attempt to convey the biblical message in contemporary English and because it is one of the most widely used among Evangelicals. However, in my reading of the Greek text I was disconcerted to find an iconoclastic bias in the NIV translation. This bias can be seen through a comparison of the NIV against the Greek original in: Romans 8:29, I Corinthians 15:49, II Corinthians 3:18, and Hebrews 1:3. It appears that the NIV is inconsistent in its translation of the Greek word eikon “εικων.” It uses the vague “likeness” in reference to Christ but uses the more direct “image” in reference to Christians. The 1611 King James Version is more consistent in its translation of “εικων.” The discovery left me with a sense of disappointment and betrayal. How can one develop a solid biblical theology if the translation one is relying on is skewed in a particular direction? Overall, the NIV is a fine translation but in this particular area it has been found wanting. This should serve as a cautionary tale to other Evangelicals that one should not be too reliant on any one translation and that if possible one should learn to read the Bible in its original languages. Biblical quotations in this posting will be from the NIV unless noted otherwise.

Old Testament Encounters With the Face of God

In the Old Testament we find a tension between God’s utter transcendence which separates us from God and God’s love which draws us to God. In Exodus 33, we find both these contrasting themes. In Exodus 33:11, we read: “The Lord would speak to Moses face to face, as a man speaks with his friend.” (cf. Deuteronomy 5:4, 34:10) This speaks of God’s nearness to us, the possibility of our being able to enter into a personal relationship with God. And yet at the end of the same chapter we see God emphasizing his utter transcendence. In Exodus 33:20, God tells Moses: “But you cannot see my face, for no one may see me and live”; and in Exodus 33:23, God tells Moses: “Then I will remove my hand and you will see my back; but my face must not be seen.”

In Genesis 32:30, we read of Jacob’s night of struggle with God in which a breakthrough was made and Jacob received the blessing of God. Jacob memorialized this event by naming the place “Peniel” (face of God) saying: “It is because I saw God face to face and yet my life was spared.” Jacob knew that for a finite, mortal being like him to have a direct encounter with the Almighty was full of peril and danger.

The word “face” (panim) can be used not just to denote God’s personal presence but also his personal blessing. In the Aaronic blessing found in Numbers 6:22-27 we find the metaphor of “face” being used to denote God bestowing his blessings on the Israelites.

The Lord bless you and keep you;

the Lord make his face shine upon you and be gracious to you;

the Lord turn his face toward you and give you peace.

There are two mentions of God’s face in this blessing. Both expressions are vivid and powerful, full of emotional impact. The phrase “make his face shine upon you” can be taken to mean God is looking at us with a big smile on his face. Do you ever notice how a smile makes a person’s face light up? Or how the smile of the mother or father causes the baby to beam with joy? God’s smiling at us tells us that he likes us, that he is favorably disposed to us, and that out of this happy relationship flows forth the divine blessings. Another phrase used in the Aaronic blessing is: “turn his face toward you.” In blessing us God turns his face towards us, that is, he accepts us and is in relationship with us. The opposite of this is God turning his back on us, doing this would signify divine rejection, our being out of relationship with God.

In I Kings 13:6, we find an interesting use of the word “face” (panim) in the matter of prayer. When the hand of King Jeroboam shriveled up as a sign of divine judgment, the king implored the prophet: “Intreat now the face of the Lord thy God, and pray for mee…. (KJV)” This interesting turn of the phrase which means to ask something of God is taken literally by the Orthodox Church when the priest stands before the icon of Christ and presents the prayers of the Church before the face (icon) of Christ.

Pictorial Representations in the Jewish Temple

The Old Testament Tabernacle was an artistic masterpiece and far from being devoid of images. For the construction of the Tabernacle God gave Moses instructions pertaining to the making of the ark of the covenant and the curtains of the Tabernacle. In light of the prohibition against the making of graven images it is something of a surprise to read that God instructed Moses to make two golden cherubim and to place these above the cover of the ark of the covenant (Exodus 25:17-22). God also instructed Moses to work the image of the cherubim into the outer curtains of the Tabernacle structure and into the curtain that separated the Holy Place from the Most Holy Place (Exodus 26:1, 31-33). Thus, the priests that served in the Tabernacle saw images of the cherubim all around them — on the outer curtains surrounding the Tabernacle as well as on the inner curtain that shielded the Most Holy Place.

Similar artistic details can be found in Solomon’s temple. For the Most Holy Place Solomon had two sculptured cherubim built (I Kings 6:23-28, II Chronicles 3:10-13). Cherubim were worked into the curtain that covered the entrance to the Most Holy Place (II Chronicles 3:14). Cherubim were also carved onto the two wooden doors for the entrance to the Most Holy Place and on the walls all around the temple (I Kings 6:31-35, 29-30). What is interesting to note is the added details of palm trees and open flowers on the walls and inner entrance. The lavish visual details here stands in sharp contrast to the stark austerity of many Protestant churches.

At the end of the book of Ezekiel is a long detailed description of the new temple. Ezekiel’s prophecy can be seen as pointing to the worship in the Messianic Age, i.e., Christian worship. Besides a description of the layout of the temple complex, the temple furnishings, the priesthood, the layout of the land, there is also a description of wall carvings (Ezekiel 41:15-26). The wall carvings consisted of palm trees and of cherubim. More specifically, the wall carvings were that of the faces of the cherubim, human or leonine. This passage tells of wall carvings all around the inner and outer sanctuary. These images were not confined to a few places in the temple but could be seen all over the new temple. This is not unlike Orthodox churches today where one sees the faces of Christ and the saints all over the church interior.

The basic lesson here is that God intended that pictorial representations or images be part of the Old Testament pattern of worship and that the use of these images did not contradict the injunction in the Ten Commandments against graven images.

The Psalms: Seeking God’s Face

Where the Pentateuch contained instructions for the ordering of Old Testament worship, the Psalms contain the heartbeat of Old Testament worship. In the Psalms we find expression of the ultimate goal of our prayers and our worship: union with God. In Psalm 27:8-9, David writes:

My heart says of you, “Seek his face!”

Your face, Lord, I will seek.

Do not hide your face from me,

do not turn your servant away in anger;

you have been my helper.

Do not reject me or forsake me, O God my savior.

Here the word “face” signifies “presence,” i.e., the psalmists desire to experience God’s presence. When we pray we enter into God’s presence, we seek to draw near to God in prayer, i.e., we “seek his face.” In Psalm 4:6, we read of David’s request to God: “Let the light of your face shine upon us, O Lord.” In Psalm 105:4, we find a similar theme: “Look to the Lord and his strength; seek his face always.”

In the Psalms are several references to God’s face shining upon his servants as a sign of his divine favor upon them. Psalm 67 begins with: “May God be gracious to us and bless us and make his face shine upon us.” In Psalm 119:135, we read: “Make your face shine upon your servant and teach me your decrees.” In Psalm 31:16, David prays: “Let your face shine upon your servant.” The use of “face” to denote God’s favor or grace in these psalms echo strongly the Aaronic Blessing Formula in Numbers 6:22-27.

In Psalm 80, which falls into the category of the psalms of penitence, we find three times the refrain:

Restore us, O God;

make your face shine upon us,

that we may be saved. (Psalm 80:3,7, and 19)

In this psalm God is asked to make his anger cease against Israel and once again restore his divine favor upon the nation. A similar reference to seeking God’s face is found in Hosea 5:15: “And they will seek my face; in their misery they will earnestly seek me.” Here seeking God’s face is part of the process of repentance, i.e., of turning from sin and turning towards God.

The Incarnation

The unfolding of God’s revelation in the Old Testament reaches its culmination with the coming of Christ. The opening lines of the book of Hebrews tells how the history of God’s progressive revelation reaches its definitive climax in Christ:

In the past God spoke to our forefathers through the prophets at many times and in various ways, but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son whom he appointed heir of all things. (Hebrews 1:1-2)

The superiority of Christ is proven by the fact that the coming of the Son supersedes all previous Old Testament revelations. In the Prologue to the Fourth Gospel the Apostle John makes a similar point:

For the law was given through Moses: grace and truth was given through Jesus Christ. No one has ever seen God, but God the One and Only, who is at the Father’s side, has made him known. (John 1:17-18; italics added)

The revelatory significance of the Incarnation lies in the fact where the prophetic message consisted of people hearing the word of the Lord, the Incarnation consisted of the Word of God coming to us in the flesh.

One consequence of the Incarnation is that God can now be seen by people. This is evident in the several passages where emphasis is placed on the fact that they have in fact seen the Son of God. John in his Gospel writes,

The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us. We have seen his glory, the glory of the One and Only, who came from the Father, full of grace and truth. (John 1:14; italics added)

John emphasizes this point repeatedly in his epistle:

That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked at and our hands have touched…. (I John 1:1; italics added)

The word “seen” is used again in I John 1:2 and 1:3. In verse 3 John insists that the Incarnation constitutes the basis for the apostolic testimony and also the basis for Christian fellowship, and that to deny the Incarnation was to deny the Christian faith (I John 4:2-3).

The significance of the Incarnation becomes clear when we examine the words used by the biblical authors to describe how Jesus reveals the Father. The writer of Hebrews writes: “The Son is the radiance of God’s glory and the exact representation (χαρακτηρ) of his being….” (Hebrews 1:3; NIV) The KJV has: “Who being the brightnesse of his glory, and the expresse image of his person….” Paul writes of Jesus Christ: “He is the image (εικον) of the invisible God.” (Colossians 1:15, cf. II Corinthians 4:4) The words used point, not to an indirect revelation, but to a direct revelation. For this reason Jesus tells Philip: “Anyone who has seen me has seen the Father.” (John 14:9, NIV; italics added)

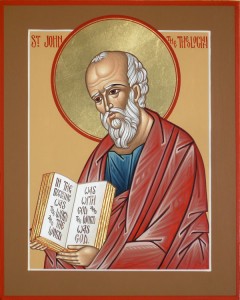

The question may be asked: So what does all this have to do with Orthodox icons? There are several reasons. For Orthodox Christians the Incarnation provides the theological basis for the use of icons. The Word made flesh also means the Word made visible. The Incarnation made it possible for humanity to behold God, to come face to face with God. Orthodoxy takes seriously the fact that in the Incarnation the Word of God took on a human face with eyes, ears, nose, chin, and lips by depicting these physical features in the icons of Christ. For the Orthodox the Bible is the verbal icon of Christ and the images are visual icons of Christ.

The Incarnation, then, marks a decisive turning point in salvation history. Isaiah’s prophecy is fulfilled: the Virgin gives birth to a son and names him “Immanuel.” David’s prayers are answered: God takes on a human face and we see him face to face. The Incarnation together with Christ’s death on the cross and his glorious resurrection constitutes the climax of God’s work of redemption in human history. Where Protestantism sees the Incarnation as a historical event, Orthodoxy sees the Incarnation as a cosmic event that continues through the Church and the icons.

The Christian Life: Becoming Icons of Christ

Our being created in the image of God has significance for our salvation in Christ. When we became Christians, a process of transformation began in which we become more and more like Christ. We are “born again” and our old corrupted nature undergoes renewal as we grow in our knowledge of who God is. Paul writes: “Do not lie to each other, since you have taken off your old self with its practices, and have put on the new self, which is being renewed in knowledge in the image (εικονα) of its Creator.” (Colossians 3:9-10) This process of transformation is actually the restoring of the imago dei that God implanted in humanity at Creation but was disfigured in the Fall (cf. Genesis 1:26-27).

In II Corinthians Paul uses Moses’ encounter with God in the Tabernacle as an illustration of how knowing Christ has a transforming impact on a person. Whenever Moses entered the Tabernacle and spent time with God, he left the Tabernacle radiant with the divine glory (II Corinthians 3:13; cf. Exodus 34:29-35). Paul writing about our situation has this to say:

But we all, with open face beholding as in a glasse the glory of the Lord, are changed into the same image, from glorie to glorie, euen as by the spirit of the Lord (II Corinthians 3:18, KJV; italics added).

And we, who with unveiled faces all reflect the Lord’s glory, are being transformed into his likeness (εικονα) with ever increasing glory, which comes from the Lord, who is the Spirit (II Corinthians 3:18; NIV; Greek original inserted).

The underlying point here is that of us beholding Christ and our being transformed “from glory to glory.” Where the NIV uses the rather vague “into his likeness,” the KJV has the more vivid “into the same image.” The same image as what? The answer seems to be: the same image as Christ! In other words, the sanctifying work of the Holy Spirit within us results in our being made into “icons” of Christ.

This passage is followed a little later by another passage which uses the face metaphor to refer to the light of Christ shining in our hearts. Paul writes:

For God, who said, “Let light shine out of darkness,” made his light shine in our hearts to give us the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Christ.” (II Corinthians 4:6)

This is a complex sentence but basically it tells us that God’s light is shining in our hearts bringing into our lives an awareness of God’s glory which is made manifest in Christ’s face. The reference to the divine glory in Christ’s face is a reference to the Transfiguration on Mt. Tabor (Matthew 17:1-3). A literal reading of the verse leads us to the understanding that God’s glory was revealed by means of the physical face with eyes, ears, nose, chin and cheeks that Jesus acquired in his Incarnation.

Our being transformed into Christ’s likeness will reach its climax at Christ’s return in glory. In Romans 8:29, Paul tells how God has predestined us “to be conformed to the likeness (εικονος) of his Son.” The KJV has the more explicit: “to be conformed to the image of his sonne.” In I Corinthians 15:49, Paul tells how on the day of resurrection we will “bear the likeness (εικονα) of the man from heaven.” The KJV has: “And as we haue borne the image of the earthy, wee shall also beare the image of the heauenly.” This idea is expressed by other apostolic writers, e.g., John who writes that “when he (Christ) appears, we shall be like him” (I John 3:2; NIV; italics added).

In summary, the biblical motif of the icon (image, face) is an important one for understanding the Christian life. God is at work in our lives, conforming us into the image of his Son. We become icons of Christ just as Christ is the icon of God! Orthodox theology has a word for this process of Christian growth: theosis — becoming partakers of the divine nature (II Peter 1:4).

The Apocalypse: We Will See God’s Face

The Apocalypse closes the biblical canon. In the first chapter the Apostle John sees the risen Christ in the fullness of his glory. John writes: “His face was like the sun shining in all its brilliance.” (Revelation 1:16) This passage echoes Daniel’s apocalyptic vision of the Son of Man whose face was like lightning (Daniel 10:6) and Jesus’ transfiguration (Matthew 17:2 and Luke 9:29). The description of the face culminates the list of details describing the risen and glorified Christ. Upon seeing Christ’s face, the Apostle John’s immediate response was to prostrate himself.

In the last chapter of Revelation, John describes the life in the age to come. What is especially interesting is Revelation 22:3-4:

No longer will there be any curse. The throne of God and of the Lamb will be in the city, and his servants will serve him. They will see his face, and his name will be on their foreheads.

The phrase “they will see his face” is the promise that although at the present time we cannot see God, the day will come when we will be in his presence and we will be able to behold his face. Standing in God’s presence and seeing the face of God summarizes the Christian hope.

Revelation 22:3-4 also describes what goes on in Orthodox worship. In the Liturgy, the Orthodox stand facing the icon of Christ the Pantocrator. As they look at the icon, “they see his face.” When people are received into Orthodoxy, the priest anoints them with the holy chrism (consecrated oil) on their foreheads in the sign of the cross. In other words, the name of the Trinity is signed on their foreheads.

A parallel theme can be found in I Corinthians 13, the well-known chapter in which Paul describes the virtues of love. He closes this elegant and moving passage with:

For we know in part and we prophesy in part, but when perfection comes, the imperfect disappears. When I was a child, I talked like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child. When I became a man, I put childish ways behind me. Now we see but a poor reflection; then we shall see face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully even as I am fully known (italics added).

For the present moment reality is hazy and confused; God is present although we cannot see him, but the day is coming when we shall see God face to face.

Thus, the icon points to the end of the present age and to the coming of the eternal kingdom of Christ. The icon of Christ is a promise that we will one day see God face to face. It is a promise that humanity’s age long exile and pilgrimage will end with a glorious homecoming in the New Jerusalem where we will gather before the throne of God.

Biblical Guidelines for the Practical Use of Icons

The purpose of icons is more than to help us think about God but to encounter God. Looking at an icon is a moment of personal encounter with the risen Lord. To look at the icon of Jesus is to see Jesus himself. We find biblical support for this in a surprising place. When Jacob met his brother Esau in the desert after many years of separation and estrangement, he told him: “For to see your face is like seeing the face of God….” (Genesis 33:10). If we take this passage literally, we can derive the principle that an ordinary face can be used depict the divine presence. However, this event cannot be read as being a theophany, consequently Jacob’s remark should be taken metaphorically. Building upon this, we get the principle that the depiction of a face can be used to depict the divine presence. When we come to the New Testament we encounter the mystery of the Incarnation in which the divine Word came down from heaven and took on a human face. Jesus told Philip: “Anyone who has seen me has seen the Father.” (John 14:9) Where Genesis 33:10 can be taken either metaphorically or indirectly, Jesus’ declaration to Philip can be taken literally and directly. Because Jesus is now risen and having ascended to heaven fills the whole universe (Ephesians 4:10), the very real possibility exists of our encountering Jesus through the icon.

In II Corinthians is a verse which provides us with a good guideline for how to look at an icon. Paul writes,

So we fix our eyes not on what is seen, but on what is unseen. For what is seen is temporary, but what is unseen is eternal (II Corinthians 4:18).

One looks at an icon not for the purpose of finding out what Jesus looked like while on earth; rather one looks at an icon in order to become aware of the glorious, risen Christ. That is why icons are full of symbolic significance. Icons point us towards the mysterious presence of Christ. To look only for the physical features of Jesus in an icon is to know Christ “after the flesh” (II Corinthians 5:16, KJV). When one looks at an icon one first sees a depiction of the physical features of Jesus Christ, after prayerful reflection one will become aware of the reality of the risen, ascended Christ.

The Evangelical-Orthodox Option

In the beginning of this paper the two different ways of reading the Bible were discussed: the regulative principle and the normative principle. The two major hermeneutical approaches used by Protestants have one thing in common: they both neglect the role of tradition. I propose that there exists a third option which is to operate on the basis that what Scripture teaches must be followed and that where Scripture is silent we follow the teachings of the Church Fathers. This is the path of the Evangelical-Orthodox. The term is not intended to describe any particular group of Christians. This is the approach of an Evangelical who affirms the divine inspiration and authority of Scripture and at the same time avoids the hermeneutical chaos of Protestantism by following the historic teachings of the Church (See End Note 1). Following this path does not entail a shift from independence to servile submission but a shift to interdependence — we use our God given talents to understand Scripture the best we can while at the same interacting with the historic teaching of the Church. The Evangelical-Orthodox recognizes that faith in Christ is not something done in autonomous independence but within the context of community, i.e., the Church.

Ancient-Future Worship?

Recently, worship among Evangelicals have undergone remarkable changes. On the one hand, there are megachurches with praise bands and slick PowerPoint presentations; and on the other hand are the Ancient-Future movement and postmodern Emergent churches which incorporate traditional icons into their worship. What these two disparate extremes have in common is a shift away from the word-centered approach to worship that has been the hallmark of Protestantism.

The question here is: Do the recent use of icons in worship among Evangelicals signal a move towards historic worship or is it more an extreme version of the Protestant normative principle? The use of the normative principle apart from tradition opens the door for creative anarchy in worship. This can be seen in icons displayed in PowerPoint accompanied by music by the band U2 to icons of a Navaho Christ. This suggests that the normative principle by itself is not enough. It seems that the recent openness to icons and historic worship among Evangelicals, while commendable still retains a very Protestant free attitude towards tradition. They seem to be cherry picking their way through both extremes with no regulatory principle.

In contrast, one finds in Orthodoxy a disciplined creativity. The use of icons in Orthodoxy is strictly regulated by traditions that regulate the content and form of icons, as well as their display and handling. This discipline reflects the fact that the Orthodox Church is a “community of memory.” (See End Note 2)

An example of a serious attempt to return to historic Christian worship can be seen in Peter Gillquist and the Evangelical Orthodox Church. This group of former Campus Crusade for Christ staff workers sought to recreate the historic church. Gillquist in Becoming Orthodox tells the story how they met people from the Orthodox Church and on the advice of Fr. Alexander Schmemann put two postcard sized icons of Christ and the Virgin Mary on the wall next to the altar (p. 131). In time this tiny step led to the entire denomination of Evangelicals being received into the Orthodox Church in 1987. What makes Gillquist’s group different from the Ancient-Future movement was their commitment to the historic Church and their willingness to follow the historic practices (tradition) to its logical conclusion — the Orthodox Church.

Are Icons Biblical?

This study of the Bible shows that the use of icons in worship can be considered biblical. But care must taken to avoid misunderstandings and confusion. It is not biblical in the sense that the Bible teaches explicitly: You must use icons in worship. However, it is biblical in the sense that the Bible shows that the use of icons is congruent with the use of pictorial representations in Old Testament Tabernacle. It is biblical in the sense that it is consistent with the biblical principle that the face of Christ denotes the divine presence. It is also biblical in the sense that it is consistent with the biblical principle that the goal of our worship and our prayer is the seeking God’s face. Furthermore, it is biblical in the sense that it affirms the Incarnation of the Divine Word who for our salvation acquired a human nature and took on a human face.

In summary, this particular study of Scripture shows that the Orthodox understanding and usage of icons in its worship is consistent with the teaching of Scripture. This is also the position taken by the early Church at the Seventh Ecumenical Council when it stated:

We preserve, without innovations, all the Church traditions established for us, whether written or not written, one of which is icon-painting as corresponding to what the Gospels preach and relate…. (italics added)

“Whether written or unwritten” is a paraphrase of Paul’s understanding of tradition stated in II Thessalonians 2:15. “Corresponding to what the Gospels preach and relate” is another of way of saying: This is Bible-based. Having shown that there is indeed a biblical basis for the use of icons in Christian worship and prayer, it is my hope that Evangelicals and Reformed Christians will take a more open minded stance to icons and will enter into a dialogue with Orthodox Christians about the meaning and significance of icons for worship and prayer.

As a result of my study of the Old and New Testaments, I came to the conclusion that there is a biblical basis for icons. Thus, for me becoming Orthodox did not mean the rejection of my Evangelicalism, but rather its fulfillment.

Robert Arakaki

End Notes

End Note 1: What I mean by the “hermeneutical chaos of Protestantism” are major issues that have long divided Protestantism: mode of baptism, the real presence of Christ in the Lord’s Supper, and form of church government all of which are based upon competing interpretations of Scripture. It is ironic and tragic that Protestantism should be united on the authority of Scripture and at the same time so divided by their differing interpretations of Scripture.

End Note 2: The term “community of memory” can be found in Robert Bellah et al. Habits of the Heart (pp. 152-155). It is used as a contrast to the radical individualism so prevalent in modern American society.

Recent Comments