The Gospel for Vampires

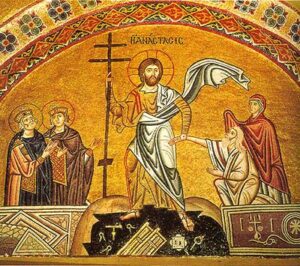

Protestants often have a hard time understanding why Orthodoxy objects so vigorously to iconoclasm. How does having or not having pictures inside churches relate to theology? The answer is that iconoclasm undermines belief in the Incarnation. Iconoclasm also undermines respect for God’s physical creation. Church history teaches us about the early heresy of Gnosticism which denied the goodness of creation and for that reason rejected Christ’s humanity. The doctrine of the Incarnation affirms that the invisible Son of God took on flesh and became man (John 1:14). In his struggle against the early heretics, the Apostle John stressed the tangible nature of Christ’s body. Christ physically entered God’s material creation so that He could be seen, heard, and touched (1 John 1:1).

Protestants often have a hard time understanding why Orthodoxy objects so vigorously to iconoclasm. How does having or not having pictures inside churches relate to theology? The answer is that iconoclasm undermines belief in the Incarnation. Iconoclasm also undermines respect for God’s physical creation. Church history teaches us about the early heresy of Gnosticism which denied the goodness of creation and for that reason rejected Christ’s humanity. The doctrine of the Incarnation affirms that the invisible Son of God took on flesh and became man (John 1:14). In his struggle against the early heretics, the Apostle John stressed the tangible nature of Christ’s body. Christ physically entered God’s material creation so that He could be seen, heard, and touched (1 John 1:1).

If Jesus appeared in visible form, then he could be depicted in images. However if he could not be depicted, then we have here a phenomenon much like vampires who while visible to humans, their reflection does not show in mirrors and who cannot be photographed. They are real and at the same also unreal. Vampire illogic is implicit in Reformed iconoclasm. Jesus’ incarnation was real while he was here on earth, but for them the incarnation in a certain sense ceased because Christ is now in heaven and out of sight. This gives us the sense that the Incarnation was more like a camera flash going off leaving an afterglow rather than a searchlight that continues to shine for all to see. Thus, Reformed iconoclasm undermines the doctrine of the Incarnation even if that is not their intent.

Vampire illogic can also be found in the Reformed understanding of the real presence in the Eucharist. Unlike their Evangelical counterparts who straightforwardly assert that the bread and wine are just symbols, the Reformed understanding is quite convoluted. They assert that there is no transformation of the bread and the wine on the communion table but that the Christians truly feed on Christ’s body and blood in heaven in the Lord’s Supper. They deny the reality of the real presence, even as they profess to hold to this ancient Christian belief. Logically speaking, they are neither here nor there. [See my article “Platonic Dualism in the Reformed Understanding of the Real Presence?”]

Prior to the Protestant Reformation, Christians saw earth and its materiality embedded in the spiritual realm. This classic worldview lays the foundation for a sacramental understanding of the cosmos. It also reflects the biblical worldview which saw the whole earth as filled with God’s glory (Isaiah 6:3). After the Reformation, a positivistic understanding of the cosmos emerged, which saw planet earth as inert matter subject to immutable scientific laws and separate from the spiritual realm. Heavenly grace while real was to be accessed through an interiorized faith, usually understood as proper understanding of doctrine combined with an emotional reaction to God’s grace, not through participation in the sacraments. Thus, implicit in Reformed iconoclasm is a secular understanding of reality.

John of Damascus (c. 675 – c. 749) grounds his defense of icons in the sacramental understanding of the cosmos.

We do not adore as gods the figures and images of the saints. For if it was the mere wood of the image that we adored as God, we should likewise adore all wood, and not, as often happens, when the form grows faint, throw the image into the fire. And again, as long as the wood remains in the form of a cross, I adore it on account of Christ who was crucified upon it. When it falls to pieces, I throw them into the fire, just as the man who receives the sealed orders of the king and embraces the seal, looks upon the dust and paper and wax as honourable in their reference to the king’s service, so we Christians, in worshipping the Cross, do not worship the wood for itself, but seeing in it the impress and seal and figure of Christ Himself, crucified through it and on it, we fall down and adore.

Behold, then, matter is honoured, and you dishonour it. What is more insignificant than goat’s hair, or colours, and are not violet and purple and scarlet colours? And the likeness of the cherubim are the work of man’s hand, and the tabernacle itself from first to last was an image. “Look,” said God to Moses, “and make it according to the pattern that was shown thee in the Mount,” (Exodus 25:40) and it was adored by the people of Israel in a circle. And, as to the cherubim, were they not in sight of the people? And did not the people look at the ark, and the lamps, and the table, the golden urn and the staff, and adore? It is not matter which I adore; it is the Lord of matter, becoming matter for my sake, taking up His abode in matter and working out my salvation through matter. For “the Word was made Flesh, and dwelt amongst us.” (John 1:14) It is evident to all that flesh is matter, and that it is created. I reverence and honour matter, and worship Him who has brought about my salvation. [Emphasis added.] Source

Here John of Damascus argues that as a result of the Incarnation, God now imparts grace to us through matter, that is, physical stuff like water, oil, wine, bread, wood and colors. For him there is no separation between spirit and matter; the two while quite different can work together.

Iconoclasm or the denial of the propriety of having images in church is no light matter. Iconoclasm is heretical because it implicitly denies the tangibility and visibility of Christ’s Incarnation. Iconoclasm is schismatic and sectarian because it entails the rejection of the Church Catholic represented by the Ecumenical Councils. Iconoclasm is not the Protestant position given the fact that Lutherans, Anglicans, and Methodists are accepting of images in churches. Iconoclasm represents only a particular sector of Protestantism, which makes it sectarian. It is schismatic because it entails a rejection of the historic Christian practice of having images in places of worship. To be an iconoclast is to divorce one’s self from the historic Church.

In keeping with the sentiment of the popular, American-cultural holiday known as Halloween we say: Beware the iconoclast!

The Gospel for Vampires

The vampire myth fascinates and draws many people to it with good reason – it speaks powerful truths about the human condition. In our fallen nature, we have become like vampires. We shun the light, preferring the darkness instead. We have become unreal, lacking substance. Lacking vitality in ourselves, we latch on to others drawing vital energies out of them in order to sustain ourselves.

The vampire myth should be viewed as a pre-Christian myth that finds fulfillment in the Good News of Jesus Christ. Missiologist Don Richardson wrote about redemptive analogies. He explained that within a culture there is usually some practice or concept that can be used to communicate the Gospel. In the vampire myth, it is the wooden stake driven into the heart of the vampire while he is sleeping in the coffin that destroys the evil vampire. The vampire’s lust for blood is a type of our hunger for the Eucharist in which we partake of Christ’s body and blood, the true food and drink (John 6:55). The destruction of the vampire is completed by leaving the corpse exposed to the sunlight (cf. Ephesians 5:8-14). The wooden stake is a type of the Cross of Christ. The vampire lying in the coffin is a type of the human soul dead in its sins and awaiting the coming of the light of the everlasting Day (Ephesians 2:1-5). However unlike the myth, in the Christian Gospel the dead soul is born anew and emerges from the coffin a resurrected human being capable of experiencing the joy of eternal life.

Sin makes us unreal. Athanasius the Great in On the Incarnation wrote about our slide into unreality due to sin:

Man who was created in God’s image and in his possession of reason reflected the very Word Himself, was disappearing, and the work of God was being undone. . . . . It was unworthy of the goodness of God that creatures made by Him should be brought to nothing through the deceit wrought upon man by the devil . . . . (§6) [Emphasis added.] Source

C.S. Lewis depicted this spiritual insight in The Great Divorce in which disembodied ghosts also end up in heaven. It is a beautiful place that is so real that the ghosts find it immensely painful to walk on the grass and each leaf is far too heavy for any of the ghosts to lift up. The way out of this dilemma is for the ghosts to repent, turn to the light, and then to proceed onward and upwards to where they will become more solid and feel less discomfort.

Christ is risen from the dead! Trampling down death by death! And upon those in the tomb bestowing life!

Conversion to Christ involves our dying to sin, our renouncing the dark and entering into the Light of Christ, and our renouncing Evil and turning to God who alone is Good (Mark 10:18). To become a Christian is to embrace the true myth of Jesus Christ, the Son of God who came down from heaven, who took on flesh and became man, who suffered a horrific death on the Cross, who was laid in the tomb, and who destroyed Death through his third day Resurrection. Unlike the popular Platonic myth that after death our spirits go to a happy place up there called heaven, the Christian myth anticipates the return of Christ, the resurrection of our bodies, a new heaven and a new earth, and the redeemed of the Lord worshiping the Trinity in New Jerusalem. The River of Life flowing from the throne of God and the Lamb in Revelation 22:1 is a symbolic reference to the Trinity. The City of God mentioned in verse 2 is a symbol of the Church. Verse 4 says: “They will see his face” – meaning that the icons of Christ are a promise that we will one day see Christ Himself face to face.

In order to accept icons one cannot just reject iconoclasm. One could mentally disagree with the Reformed position and view icons appreciatively like one would in a museum setting. I remember talking with an Episcopalian deaconess who enjoyed painting icons in the traditional Byzantine fashion but balked at the kissing of icons. According to the Seventh Ecumenical Council, to accept icons means that we venerate icons. Usually, this takes the form of kissing the icon as a sign of love and respect for the person depicted in the icon. To kiss an icon is a very tangible, even carnal, act that in a very profound way manifests the reality of the Incarnation. It is also a very concrete way of showing one’s solidarity with the early Church. In Orthodoxy we do not just believe in the Incarnation as a theological concept; rather we participate in the reality of the Incarnation through physical actions like getting wet in baptism, being present at the Divine Liturgy, feeding on the body and blood of Christ in the Eucharist, being anointed with holy oil, kissing the Gospel book, and kissing the icons of Christ and the saints. Being Orthodox is not just about being theologically correct as it is about becoming real, integrated beings through union with Christ.

Robert Arakaki

References

St. Athanasius. On the Incarnation. St. Vladimir Seminary Press. Originally published 1944.

St. John of Damascus. Apologia of St. John Damascene Against Those Who Decry Holy Images. Part II. Balamand.edu.

Don Richardson. Eternity in Their Hearts.

CS Lewis. The Great Divorce.

Robert Arakaki. 2012. “Platonic Dualism in the Reformed Understanding of the Real Presence?” OrthodoxBridge.

Robert Arakaki. 2013. “Christian Images Before Constantine.” OrthodoxBridge.

Robert Arakaki. 2016. “Do We Need a Photo ID of Christ?” OrthodoxBridge.

Recent Comments