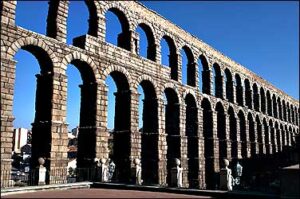

Ancient Roman Aqueduct Bridge

As a follow up on my previous posting: “Irenaeus of Lyons: Contending for the Faith Once Delivered,” I will be presenting excerpts from his Against the Heretics with some short comments about how they relate to our present situation. In a comment thread I noted that Irenaeus’ Against the Heretics contains lengthy detailed discussions of the Gnostic heresy with nuggets of wisdom here and there. I am presenting these excerpts as a convenience to the readers.

I drew the excerpts from a number of sources: Cyril Richardson’s Early Christian Fathers, Robert M. Grant’s Irenaeus of Lyons, and volume 1 of the Ante-Nicene Fathers series — retail or pdf file. In addition, I used On the Apostolic Preaching published by St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

Irenaeus’ Creed

Now the Church, although scattered over the whole civilized world to the end of the earth, received from the apostles and their disciples its faith in one God, the Father Almighty who made the heaven, and the earth, and the seas, and all that is in them, and in one Christ Jesus, the Son of God, who was made flesh for our salvation, and in the Holy Spirit, who through the prophets proclaimed the dispensations of God (AH 1.10.1, Richardson 1970:360).

Comment: Here we see the outline of what would become known as the Apostles Creed and the Nicene Creed. This creed was not so much a personal statement of faith as it was part of the Tradition of the Church received from the Apostles. As a Protestant familiar with denominational diversity I was fascinated by the doctrinal unity of the early Church. Either one was Orthodox or one was a heretic.

Our Salvation in Christ

So, then, since the Lord redeemed us by his own blood, and gave his soul for our souls, and his flesh for our bodies, and poured out the Spirit of the Father to bring about the union and communion of God and man–bringing God down to men by [the working of] the Spirit, and again raising man God by his incarnation–and by his coming firmly and truly giving us incorruption, by our communion with God, all the teachings of the heretics are destroyed (AH 5.1.1, Richardson 1970:386).

Comment: A close reading of this passage shows that Irenaeus did not present salvation in terms of forensic justification but in terms of reconciliation and communion. Salvation here is not understood in terms of legal righteousness but in terms of our being united with the Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Here we also see the importance of the Incarnation: Christ assuming human nature for our salvation.

Our Calling in Life: to glorify God

For the glory of God is a living man; and the life of man consists in beholding God. (AH 4.20.7; ANF vol. I p. 490)

The glory of God is man fully alive; and man fully alive is man glorifying God. (popular paraphrase)

Comment: This popular quote has often been taken out of context and understood to mean that by being ourself, i.e., doing our own thing, we are glorifying God. But taken in its proper context it gives a compelling vision of human existence. As live out our lives here on earth we do all things for the glory of God and the apex of our human existence is our giving God glory during the Liturgy. What we see in Irenaeus is a sacramental understanding of human existence, i.e., that our lives, our whole beings are meant by God the Creator to be vessels of divine grace.

The Authority of Scripture

For we learned the plan of our salvation from no others than from those through whom the gospel came to us. They first preached it abroad, and then later by the will of God handed it down to us in Writings, to be the foundation and pillar of our faith (AH 3.1.1, Richardson 1970:370).

So the apostolic tradition is preserved in the Church and has come down to us. Let us turn, then, to the demonstration from the Writings of those apostles who recorded the gospel, in which they recorded their conviction about God, showing that our Lord Jesus Christ is the Truth, and in hin him is no lie…. (Richardson 1970:376)

Comment: What we find in Irenaeus is the not the dichotomy of Scripture over Tradition (the Protestant sola scriptura position) or Church over Scripture (the Roman Catholic papal magisterium position) but Scripture in Tradition. For Irenaeus the New Testament and the four Gospels comprise Apostolic Tradition in written form. As the written form of Apostolic Tradition, the New Testament writings did not supersede but complemented the oral form of Apostolic Tradition (see II Thessalonians 2:15). As Irenaeus noted the Gospel was first preached (oral transmission) then later “handed down” in written form. Scripture and oral tradition complement each other because they both belong to the Apostolic Tradition.

Holy Tradition

Even if the apostles had not left their Writings to us, ought we not to follow the rule of the tradition which they handed down to those to whom they committed the churches? Many barbarian peoples who believed in Christ follow this rule, having [the message of their] salvation written in their hearts by the Spirit without paper and ink (AH 3.4.1-2, Richardson 1970:375).

Comment: This is one of the clearest refutation of the Protestant sola scriptura from the early Church. This does not rule out or exclude the importance of Scripture but shows that Christian missions can be done through the oral proclamation of the Good News of Christ. The history of Orthodox missions contains examples of Orthodox missionaries who first proclaimed the Good News of Christ in oral form then later on translated the Gospels into the native language, e.g., Herman of Alaska and the Unangax̂ or Aleuts.

Ordination of Deacon

Apostolic Succession

The tradition of the apostles, made clear in all the world, can be clearly seen in every church by those who wish to behold the truth. We can enumerate those who were established by the apostles as bishops in the churches, and their successors down to our time, none of whom taught or thought of anything like their [the Gnostics] mad ideas (AH 3.3.1, Richardson 1970:371).

Comment: What validates a church? What markers point to a bunch of people being a church? The Protestant approach is to take the Bible in hand and attempt to show that what they believe is in line with what the Bible teaches. For many just having a Bible there in the services and a speaker talking about the Bible qualifies them to be a church.

For Irenaeus these are not enough. For him a church is validated if they can show they are part of a chain of apostolic tradition. This chain consists of one bishop succeeding another and so on. Apostolic succession is more than a connection based on proper ritual but on the faithful transmission of the Apostles’ teachings, e.g., the Gospel, right doctrine, worship, and church order. Irenaeus’ position on the episcopacy is supported by Ignatius of Antioch, an early Christian who knew the Apostles, who insisted that nothing be done apart from the bishop.

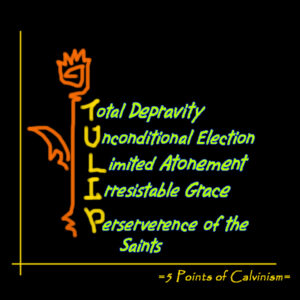

Calvin insisted that the true church is marked by the right preaching of Scripture, the right administering of the Sacraments, and church discipline but oddly enough made no mention of the episcopacy. Here Calvin has parted ways with Irenaeus and the early Church.

Many Protestants believe that they have apostolic succession because they share in the same teachings as the Apostles. But this is a highly problematic claim in light of what Irenaeus wrote. First, the theological differences among denominations, many contradicting each other, makes their claim that they have preserved the “pure teachings” of the Apostles suspect. Second, their approach is disembodied. Like the Gnostics they focus on the intellect and disregard the bodily reality (the historic Church). Third, Protestantism’s origin in a schism with Rome rules out any historic succession.

The Unity and Catholicity of the Christian Faith

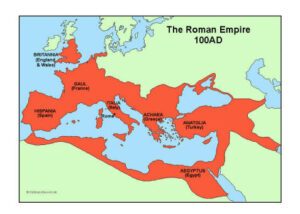

Having received this preaching and this faith, as I have said, the Church, although scattered in the whole world, carefully preserves it, as if living in one house. She believes these things [everywhere] alike, as if she had but one heart and one soul, and preaches them harmoniously, teaches them, and hands them down, as if she had but one mouth (AH 1.10.2, Richardson 1970:360).

Comment: This passage was probably one I read years ago and stuck in my mind since then. It haunted me because as a Protestant I was keenly aware of the denominational diversity among churches and even within denominations. When I was an Evangelical seeking to bring biblical renewal to the liberal United Church of Christ I was struck by the clashing theologies within the same denomination and how in the early Church doctrinal orthodoxy and church unity formed an organic whole.

Baptism

So, faith procures this for us, as the elders, the disciples of the apostles, have handed down to us; firstly it exhorts us to remember that we have received baptism for the remission of sins, in the name of God the Father, and in the name of Jesus Christ, the Son of God, [who was] incarnate, and died, and was raised, and in the Holy Spirit of God; and that this baptism is the seal of eternal life and rebirth unto God, that we may no longer be sons of mortal men, but of the eternal and everlasting God…. (On the Apostolic Preaching 1.1, p. 42)

Comment: For many Evangelicals baptism is symbolic, an outward sign of an inward grace but for the early Christians baptism was means of our rebirth in Christ and our receiving the forgiveness of sins. Baptism in the early Church was part of the Tradition received from the Apostles through their successors the bishops.

Eucharist

Vain above all are they who despise the whole dispensation of God, and deny the salvation of the flesh and reject its rebirth, saying that it is not capable of incorruption. For if this [mortal flesh] is not saved, then neither did the Lord redeem us by his blood, nor is the cup of the Eucharist the communion of his blood, and the bread which we break the communion of his body. …. For when the mixed cup and the bread that has been prepared receive the Word of God, and become the Eucharist, the body and blood of Christ, and by these our flesh grows and is confirmed, how can they say that flesh cannot receive the free gift of God, which is eternal life since it is nourished by the body and blood of the Lord, and made a member of him? As the blessed Paul says in the Epistle to the Ephesians, that we are members of his body, of his flesh and his bones (AH 5.2.2-3, Richardson 1970:387-388).

Comment: In the Evangelical circle I moved in it was understood that in the Lord’s Supper the bread and the grape juice were just symbolic and nothing else. But reading Irenaeus taught me that the early Christians believed that in the Eucharist the bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ. A close reading of this passage by Irenaeus shows how for him the Eucharist is key to our flesh (physical body) receiving incorruptibility through union with Christ.

Salvation Through Repetition

So the Lord now manifestly came to his own, and, born by his own created order which he himself bears, he by his obedience on the tree renewed [and reversed] what was done by disobedience in [connection with] a tree; and [the power of] that seduction by which the virgin Eve, already betrothed to a man, had been wickedly seduced was broken when the angel in truth brought good tidings to the Virgin Mary, who already [by her betrothal] belonged to a man (AH 5.19.1, Richardson 1970:389).

Comment: Why the Incarnation? The Western answer is that Christ took on human nature so that he could suffer on the cross as a substitutionary atonement for the sins of humanity. Furthermore, it is believed that Christ’s legal merits could be transferred over to those who believe in him. Here Irenaeus is teaching that Christ took on human nature so he could be the Second Adam who lived out the life the First Adam failed to live. If we join ourselves to Christ through baptism we are no longer part of the First Adam who sinned and fell into corruption. We are part of the Second Adam who lived completely for God and who enjoyed unbroken union with God the Father.

The True Gnosis (Knowledge)

This is true Gnosis: the teaching of the apostles, and the ancient institution of the church, spread throughout the entire world, and the distinctive mark of the body of Christ in accordance with the succession of bishops, to whom the apostles entrusted each local church, and the unfeigned preservation, coming down to us, of the scriptures, with a complete collection allowing for neither addition nor subtraction, a reading without falsification and, in conformity with the scriptures, so interpretation that is legitimate, careful, without danger of blasphemy (AH 4.33.8, Grant 1997:161).

Comment: What we see here is how Irenaeus’ theology was simultaneously both evangelical and catholic. This passage describes well Holy Tradition as an integrated package so to speak. The local church cannot exist apart from Scripture, the Apostles’ teachings, and the bishops the successors to the Apostles. What Irenaeus described here is so different from the understanding I had as an Evangelical that the church consisted of a group of people who came together on their own to study the Bible, pray and sing songs of worship. Irenaeus’ emphasis on Apostolic succession was so different from Evangelicalism’s emphasis on Bible commentaries, theological journals, radio preachers, and televangelists with their easy to understand messages.

The Challenge for Protestants

Reading Irenaeus is both inspiring and challenging for Protestants. His defense of the Christian Faith against the early heretics is inspiring. Yet reading Irenaeus is also challenging because he did not operate on the basis of sola scriptura (Scripture alone) but on the basis of Apostolic Tradition. While I was at seminary I could not ignore Irenaeus because he was regarded as the best Christian theologian in the second century. Furthermore, Irenaeus gave me a window into how the early Christians did theology.

Reflecting on Irenaeus helped me to appreciate the Orthodox Church. Initially, I thought the Orthodox Church was strange and off-based, but after reading Irenaeus I came to the realization that if Irenaeus were to visit a Protestant church today he would think that it was Protestantism that was strange and off-based!

The fact that even Calvin differed from Irenaeus made me reconsider my Protestant theology. Did I prefer a theology that was formulated in the 1500s or in the second century? Did I prefer a theology formulated by university trained scholars or by those who learned from the Apostles of Christ? In time questions like these helped me in my journey to Orthodoxy.

Robert Arakaki

Recent Comments