Monergism and the Heresy of Monotheletism

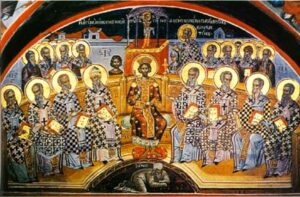

Much of the Reformed tradition’s Christology and Trinitarian theology came out of the ancient Ecumenical Councils. There were many gatherings in the early Church. Many were local councils but the great Councils made decisions that would ensure the wellbeing of the entire Church (hence the name “Ecumenical”). These gatherings followed the precedent by the Jerusalem Council in Acts 15 and are the fulfillment of Christ’s promise that the Holy Spirit would guide the Church into all truth (John 16:13). The early Church was challenged by heresies and it repudiated these heresies and defined right doctrine through gatherings of church leaders that represented the whole church, these came to be known as Ecumenical Councils. For example, the first Ecumenical Council (Nicea I in AD 325) repudiated the heresy that Christ was a created being and affirmed the divinity of Jesus Christ, the second Ecumenical Council (Constantinople I in AD 381) affirmed the divinity of the Holy Spirit, the third Ecumenical Council (Ephesus in AD 431) affirmed the two natures of Christ (see Kallistos Ware’s The Orthodox Church pp. 20 to 35).

The sixth Ecumenical Council repudiated monotheletism, the heresy that Jesus Christ had only a divine will, and affirmed that Christ possessed both a divine and a human will. While many Protestants may not have heard of the heresy of monotheletism, the issue is crucial to having a healthy orthodox Christology. It is not an obscure minor theological issue but one of tremendous implications for proper Christology and one that required action by an ecumenical (universal) council. Protestantism’s historical amnesia has often made it vulnerable to erroneous doctrines. I urge my Reformed friends to take seriously what I have to say about Reformed monergism and the heresy of monotheletism.

The Reformed insistence on the priority of the divine will over human will (monergism) parallels the heresy of monotheletism — the teaching that Christ did not have two wills, only a divine will. In repudiating monotheletism the Sixth Ecumenical Council affirmed that Christ’s humanity possessed a free will that worked in harmony with the will of the divine Logos. This was not an arbitrary ruling but an outworking of the Chalcedonian Formula’s teaching that Jesus Christ is fully God and fully man. Thus, to be human means having a body, a mind, a soul, and a will. To deny any of these leads to a defective and heretical Christology. This understanding of Christ’s human nature having a fully human will like Adam’s and our’s leads to the affirmation that humans have a free will as well, albeit one injured by the Fall and in need of healing. By assuming the totality of human nature, Christ was able to bring about our salvation. Gregory of Nazianzen wrote:

For that which He [Christ] has not assumed He has not healed; but that which is united to His Godhead is also saved. If only half Adam fell, then that which Christ assumes and saves may be half also; but if the whole of his nature fell, it must be united to the whole nature of Him that was begotten, and so be saved as a whole (Ep. CI, To Cledonius the Priest Against Apollinarius; NPNF Series 2 Vol. VII p. 440).

This is quite different from the Reformed understanding that the Fall result in our wills being totally depraved, “neither able nor willing to return to God” according to the Canons of Dort.

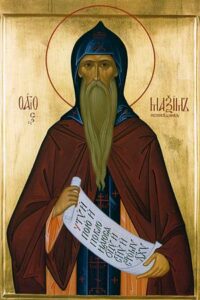

The Cappadocians assigning priority to the hypostases shaped not just Orthodoxy’s understanding of the Trinity but also Maximus the Confessor’s understanding of the Incarnation as instrumental for our salvation. [Note: Readers who want to better understand the issues involved in the monothetism controversy are advised to get Maximus the Confessor (1996) edited by Andrew Louth.]

Maximus wrote:

Because of this, the Creator of nature himself — who has ever heard of anything so truly awesome! — has clothed himself with our nature, without change uniting it hypostatically to himself, in order to check what has been borne away, and gather it to himself, so that, gathered to himself, our nature may no longer have any difference from in its inclination. (Maximus the Confessor Letter 2 in Louth p. 91)

Orthodoxy’s emphasis on the hypostasis influences its understanding of the Incarnation, the sacraments, and theosis.

Monergism vs. Free Will

The Western emphasis on Being leads to determinacy and to Calvin’s insistence on God’s absolute sovereignty. In his attempt to construct a logically coherent theology Calvin has created other problems. The doctrine of Irresistible Grace contains an internal contradiction: God’s free gift of grace is based on compulsion. Bishop Kallistos Ware wrote:

Where there is no freedom, there can be no love. Compulsion excludes love; as Paul Evdokimov used to say, God can do everything except compel us to love him (Ware 1986:76; emphasis in original).

If there is no free will, then there is no genuine love, nor can there be genuine faith. In Calvinistic anthropology, humans do love God and one another freely but with the haunting a priori that their love is a mere consequence of God’s ordained decree, not because of their free choice.

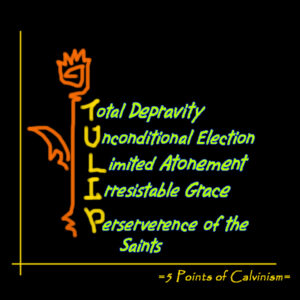

The Reformed tradition does affirm free will but qualifies it to the extent that one wonders whether free will is essential to human existence. Basically, the Reformed position on human free will can be summed up in the following:

(1) Humanity possessed free will prior to the Fall (Dort Article 1 “The Effect of the Fall on Human Nature”; Westminster Confession IX.2);

(2) Humanity lost all capacity for free will after the Fall (Dort Article 3 “Total Inability,” Westminster IX.3);

(3) Faith in Christ is the result of divine election and divine grace working on us, (Dort Article 12 ‘Regeneration a Supernatural Work, Westminster X.1-2);

(4) The perseverance (preservation) of the saints is due solely to divine grace (Dort Article 8 “The Certainty of this Preservation,” Westminster Chapter XVII.2); and

(5) Free will is restored to humanity when they are in the “state of glory” (Westminster Chapter IX).

The last statement doesn’t make sense. Logically, it would mean the possibility of apostasy in the age to come. Thus, according to the Reformed theological system the only time humanity ever possessed the freedom with respect to their relationship with God was prior to the Fall but not after.

The Orthodox approach to free will is that humans possessed an undistorted free will prior to the Fall but after the Fall human free will became damaged or wounded. Christian conversion is understood as our free response to God’s grace by trusting in Christ and our participation in the life of the Church, the Body of Christ. Orthodoxy’s affirmation of free will after the Fall allows for the possibility of people falling away, but it also allows for the possibility of restoration. The Orthodox sacrament of confession is based on our turning back to God (repentance) and the mercies of God. God in his mercy will welcome us back but this is contingent on our choosing to come back home like the lost Prodigal Son (Luke 15). The father in Jesus’ great parable waited, he did not compel. For this reason Orthodoxy insists that the eternal destiny of individuals is a mystery.

The ascetic disciplines prescribed by the Orthodox Church are based on prayer and the denying of the passions; through these spiritual exercises our wills along with our minds are sanctified and redeemed. The Orthodox approach to sanctification is therapeutic and progressive. As we grow in prayer and in our love for God and our neighbor our wills damaged by the Fall are restored to the health and integrity God intended for us. During Lent the Orthodox Church warns her members against legalism. This is in recognition that a legalistic approach to the Christian life being based on fear and compulsion is the opposite of a spiritual life based on contrition for sins and a yearning for God.

The Possibility of Free Will

Orthodoxy affirms free will because humanity being created in the divine image is foundational to its theology. Eastern Orthodoxy’s anthropology being rooted in a trinitarian understanding of God leads us to a soteriology grounded in freedom as relationship, i.e., the freedom of love. Kallistos Ware wrote:

Without freedom there would be no sin. But without freedom man would not be in God’s image; without freedom man would not be capable of entering into communion with God in a relationship of love (Ware 1986:76).

Being created in the image of the Triune God means not only rationality but also morality, that is, the freedom and ability to choose. The two together form the basis for our being able to love God and one another. Nor is there any notion here in Orthodox anthropology of free will stealing any of God’s glory, frustrating God’s purposes, or granting merit to man because of his choice. These are all problems invented by Western theological categories.

There is a profound difference in the way the West and Orthodoxy understand freedom. In the West freedom is understood to arise from perfect self-possession, self-autonomy, and self-direction, but for the Orthodox freedom arises from ecstasis and self-transcendence, going beyond ourselves (Lacugna 1991:261). The freedom spoken of here is based on the communion of persons, not the fulfillment of autonomous individuals. Zizioulas draws the distinction between the individual and the person noting that the individual becomes a person by loving and being loved (Zizioulas 1985:48-49). True human freedom means going beyond our individual self and becoming open to others which finds its ultimate fulfillment in union with Christ and life in the Trinity.

Eastern Orthodoxy’s emphasis on the person (hypostasis) leads to freedom and relationality.

The fact that God exists because of the Father shows that His existence, His being is the consequence of a free person; which means, in the in the last analysis, that not only communion but also freedom, the free person, constitutes true being. True being comes only from the free person, from the person who loves freely–that is, who freely affirms his being, his identity, by means of an event of communion with other persons (Zizioulas 1985:18; emphasis in original).

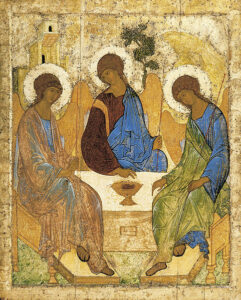

This in turn opens the way for perichoresis, the idea that the three Persons of the Trinity mutually inhere in one another (LaCugna 1991:270 ff.). Perichoresis lays the foundation for the idea of persons in communion, both in terms of intradivine relations within the Trinity and our being invited (elected) into that interpersonal communion. (See John of Damascus’ De Fide Orthodoxa Chapter VIII (NPNF Vol. 2 page 11 Note 8).)

Salvation in Christ has an eschatological element. Justification, regeneration, and sanctification represent the beginning of our salvation in Christ. The ultimate goal of our salvation is theosis, becoming sharers in the divine nature and the kingdom of God (see II Peter 1:4). Kallistos Ware wrote:

The final end of the spiritual Way is that we humans should also become part of this Trinitarian coinherence or perichoresis, being wholly taken up into the circle of love that exists within God (1986:34; emphasis in original).

At the heart of Orthodoxy is the vision of life in Christ as communion with the Holy Trinity, the three divine Persons forever united in love. This interpersonal understanding of salvation can be found in John 17:21: “May they all be one: as thou, Father, art in me, and I in thee, so may they also be one in us.”

The Question of Universalism

One of the greatest challenge to Calvinism is the question: How can a loving God send people to hell? Calvin’s answer is God’s just and inscrutable sovereignty.

We assert that, with respect to the elect, this plan was founded upon his freely given mercy, without regard to human worth; but by his just and irreprehensible but incomprehensible judgment he has barred the door of life to those whom he has given over to damnation (Institutes 3.21.7, Calvin 1960:931; italics added; see also Institutes 3.21.1, Calvin 1960:922-923).

Many people’s reaction to predestination has been one of revulsion. Philip Schaff in his concluding remarks to his survey of Calvin notes:

Our best feelings, which God himself has planted in our hearts, instinctively revolt against the thought that a God of infinite love and justice should create millions of immortal beings in his own image–probably more than half of the human race–in order to hurry them from the womb to the tomb, and from the tomb to everlasting doom! And this not for any actual sin of their own, but simply for the transgression of Adam of which they never heard, and which God himself not only permitted, but somehow foreordained. This, if true, would indeed be a “decretum horribile” (Schaff 1910:559).

The underlying ethos of Calvinism is not the warm heart religion of popular Evangelicalism or the fervent emotionalism of Pentecostalism, but the more stern and demanding religion that calls for submission and domination. Karl Barth characterized the spirit of Calvinism:

Calvin is not what we usually imagine an apostle of love and peace to be. …. What we find is a hard and prickly skin. The blossom has gone, the fruit has not yet come. An iron age has come that calls for iron believers” (1922:117).

In reaction to the Calvinist double predestination liberal Protestantism propounded the doctrine of universalism: All are destined to go to heaven. However attractive such a doctrine may be, it suffers from a flaw similar to that found in Calvinism. Underlying Liberalism’s sunny optimism is a blithe disregard towards human agency. A friend of mine who served on the pastoral staff of a large liberal mainline Protestant church once asked me what I thought about her colleague’s teaching that everyone will be in heaven. I answered: “You mean everyone is going to end up in heaven, whether they want to be there or not?”

Ironically, Liberalism’s universalism is a mirror image of Calvinism’s double predestination. Where Calvinism believes in a God who arbitrarily selects some to be saved regardless of their choice), Protestant Liberalism believes in a God who indiscriminately selects all to be saved (irregardless of their choice). Liberalism ultimately denies to all humanity the free choice of hell. Calvinism despite its talk of grace and mercy is determined to deny to all humanity the free choice of heaven.

The Orthodox response to this question is: “God doesn’t send anyone to hell. People choose hell when they choose life apart from God.” To put it another way, God “sends” only those who have freely chosen hell for themselves. Bishop Kallistos Ware wrote:

St Isaac the Syrian says, ‘It is wrong to imagine that sinners in hell are cut off from the love of God.’ Divine love is everywhere, and rejects no one. But we on our side are free to reject divine love: we cannot, however, do so without inflicting pain upon ourselves, and the more final our rejection the more bitter our suffering (in Ware 1986:182).

Thus, the Orthodox understanding of hell is more just, compassionate, and tragic in comparison to the Reformed view. While Orthodoxy disallows universalism as a dogma, the question as to how many shall be ultimately saved is left open. For a discussion of the complex nature of this question see Kallistos Ware’s “Dare We Hope for the Salvation of All?” in The Inner Kingdom (2000:193-215).

Summary

TULIP forms a coherent theological system that explains the Reformed doctrine of predestination. When we consider TULIP as a whole, its underlying premises, and its consequences we find it incompatible with Orthodoxy and hopefully unacceptable to others as well. The doctrines of Total Depravity and Irresistible Grace by denying the basis for human free will undermine the basis for faith and love. This denial of free will constitutes a denial of the core of human existence, the imago dei. This denial of human free will implies the heresy of monotheletism — the denial that Christ’s human nature had a free will. The doctrine of Limited Atonement is alien to Orthodoxy for two reasons: (1) it is based upon the notion of quantifiable legal merit, and (2) it sets limits on God’s infinite love. Where the initials T and I relate to the Reformed understanding of human nature, the initials U and P relate to their understanding of God. The doctrines of Unconditional Election and the Preservation of the Saints uphold God’s absolute sovereignty in our salvation. This understanding of God as an arbitrary omnipotent Monarch can be traced to the Western Augustinian tradition which emphasizes the divine Essence as the basis for unity of the Trinity. This forms the basis for the forensic approach to salvation which emphasizes legal righteousness and the transference of legal merit. Orthodoxy following the Cappadocian Fathers locates the unity of the Godhead in the Person of the Father. This emphasis on the Person lays the basis for the understanding of God as eternal communion of Persons: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. It also leads to Chalcedonian Christology which teaches that Christ’s two natures are united in one Person for our salvation. This emphasis on the Person informs the Orthodox approach to salvation: the need for personal faith in Christ, salvation as union with Christ and in the Church; theosis as personal union with Christ that transforms us, and eternal life as communion with the Triune God.

The Goal of Our Salvation: Life in the Trinity

When we read the famous opening lines of the Westminster Shorter Catechism — Q. What is the chief end of man? A. Man’s chief end is to glorify God and enjoy him forever — we find missing any reference to the Trinity and any understanding of eternal life as communion with God. This is not surprising in light of the analysis we just did showing how the Western Augustinian approach to the Trinity tends to emphasize the Essence of the Godhead over the communion of Persons. Orthodoxy has a quite different vision of eternal life. It anticipates eternal life as living in communion with the Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. St. Isaac the Syrian wrote:

Love is the kingdom which the Lord mystically promised to the disciples, when he said that they would eat in his kingdom: ‘You shall eat and drink at my table in my kingdom’ (Luke 22:30). What should they eat and drink, if not love?

When we have reached love, we have reached God and our journey is complete. We have crossed over to the island which lies beyond the world, where are the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit: to whom be glory and dominion. May God make us worthy to fear and love him. Amen. (in Ware 1986:51)

Robert Arakaki

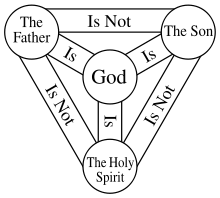

Western Christianity’s foregrounding of the ousia (being) of God has led to logical difficulties. It has resulted in theologians having to make statements that resemble Zen koans used by Buddhist monks. A common explanation often goes like this: the Father is God, the Son is God, the Holy Spirit is God; but the Son is not the Father, and the Son is not the Holy Spirit; but there is not three gods but only one God. Formulation like this often frustrate and bewilder many. It is radically different from the Eastern understanding of the Trinity as the communion of three Persons who share in the same Essence.

Western Christianity’s foregrounding of the ousia (being) of God has led to logical difficulties. It has resulted in theologians having to make statements that resemble Zen koans used by Buddhist monks. A common explanation often goes like this: the Father is God, the Son is God, the Holy Spirit is God; but the Son is not the Father, and the Son is not the Holy Spirit; but there is not three gods but only one God. Formulation like this often frustrate and bewilder many. It is radically different from the Eastern understanding of the Trinity as the communion of three Persons who share in the same Essence.

Recent Comments