“The Impotence of Calvinism?” by Spencer Boersma

Spencer Boersma posted “The Impotence of Calvinism?” on After Orthodoxy? In it he presents a hypothetical conversation between a Young Man and his Calvinist pastor about his struggle to live a holy life and God’s preservation of the elect.

Here is a partial excerpt of the conversation.

YM: A Young Man turned to his pastor and said, “Pastor, why did I sin?”

P: “Because you did not obey God, son,” the Pastor replied.

YM: “But this time it was like I could not stop myself, no matter how hard I tried. Pastor, am I responsible for the sins that I do that are out of my control?”

P: “Why yes. After all, you did them. You are always in control. You never have an excuse.”

YM: “But Pastor, don’t you say in your sermons that God is sovereign. God is in control, not me?”

P: “Yes he is, always. So, you should ask him for the strength to obey.”

YM: “I did and he didn’t give me the strength this time…”

P: “…I don’t think that is what happened. He probably did provide and you did not act on that provision.”

YM: “Well, maybe. But if that is the case, why did he cause me not to act on it? Why did he not give me the strength to act on the strength that he gave?”

P: “What? No. No. No. You are confused. You do not understand. God does not cause you to sin. You do.”

YM: “But I thought you said he was sovereign over everything, that he causes all things?”

P: “Yes, but not that.”

More

One troubling aspect about the dialogue is that the pastor is so busy debating theology with a member of his flock that he fails to practice the healing of souls. It seems that the pastor is applying rigorous logic when mercy and compassion are what the Young Man so desperately needs. The dialogue ends in both sides frustrated and at an impasse. This pastoral impasse is rooted in a theological conundrum that lies at the heart of Reformed theology – its monergistic approach to salvation. Boersma writes:

Of course, with our classical Calvinistic circles, this question cannot be answered without, as we see with the pastor, getting rather frustrated and upset. Even then, no helpful answer is really given that would comfort the young man in the despair of his sin. Does God love me as a disobedient sinner? Does [God] not love me enough to destroy the sins that have enslaved me? The answer, for the Calvinist, is left shrouded in terrifying mysticism, paralyzed the inability for the Calvinistic account of God to answer the question of whether or not God has truly elected a person to salvation (emphasis added).

Boersma closes with a quote from Isaiah 63:15-17 in which the prophet asks why God has hardened the hearts of the Israelites. While this verse may bring some comfort to the troubled Young Man, it still does not address the theological roots of his problem. Many Reformed pastors or theologians take a different tack counseling: “Do not concern or trouble yourself with God’s eternal decrees or election. Your duty is to ‘trust and obey,’ to be faithful to ‘those things that have been revealed’ (Deuteronomy 29:29).”

In this blog posting I will: (1) discuss the Reformed perspective on the Christian life and (2) present the Orthodox perspective on the Christian life. Then in the next blog posting I will describe the different approach an Orthodox priest might take to the Young Man’s predicament.

The Reformed Perspective – Christian Life as Imparted Grace to the Elect

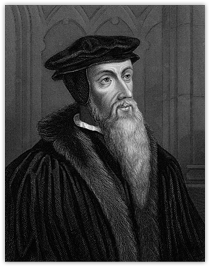

John Calvin

The foregoing dialogue is really about the Reformed doctrine of the preservation (perseverance) of the saints. The pastor faithfully and accurately reflected Calvin’s teaching on the Christian life.Calvin wrote:

For perseverance itself is indeed also a gift of God, which he does not bestow on all indiscriminately, but imparts to whom he pleases. If one seeks the reason for the difference–why some steadfastly persevered, and others fail out of instability–none occurs to us other than that the Lord upholds the former, strengthening them by his own power, that they may not perish; while to the latter, that they may be examples of inconstancy, he does not impart the same power (Institutes 2.5.3; Calvin 1960:320, emphasis added).

According to Calvin, if one belongs to the elect one will have received divine grace (power) to resist sin, but for those not part of the elect God in his inscrutable wisdom has withheld his grace from them. The element of our human response or struggle to live holy lives has no part in Calvin’s monergistic understanding of salvation. Based on what Calvin wrote the Young Man has reason to be concerned about his salvation.

This has led to Reformed theologians devoting considerable energies to addressing this problem by asserting the possibility of the certainty of salvation. The Westminster Confession of Faith teaches:

This perseverance of the saints depends not upon their own free will, but upon the immutability of the decree of election, flowing from the free and unchangeable love of God the Father; upon the efficacy of the merit and intercession of Jesus Christ, the abiding of the Spirit, and of the seed of God within them, and the nature of the covenant of grace: from all which arises also the certainty and infallibility thereof. (Chapter XVII.2; emphasis added. See also Chapter XVIII and the Westminster Larger Catechism Q. 80)

The Westminster divines underscored the divine decrees and the denial of human free will before addressing the assurance of salvation. What I find problematic about the Reformed position on the assurance of salvation is the extreme language used. The unqualified use of “certainty” and “infallibility” seems to imply that they have X-ray vision capable of discerning the inscrutable will of God. The Orthodox position is that the eternal destiny of individuals is a mystery but that we put our confidence in God’s goodness and mercy.

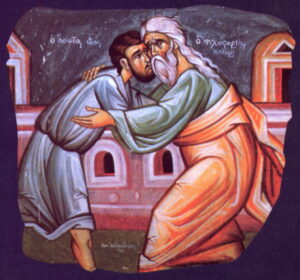

The Orthodox Perspective — Christian Life as Struggle and Journey

God’s mercy is foundational for Orthodox spirituality. God in his mercy will welcome back the repentant sinner. In the Sunday Liturgy one hears repeatedly: “Lord have mercy!” Orthodox Christians are en-couraged to cultivate a heart of repentance by saying repeatedly the Jesus Prayer: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.” Consistent attendance at the Sunday Liturgy will give one a growing awareness that God is not so much the stern judge as He is the merciful father waiting for the prodigal to return home.

God’s mercy is foundational for Orthodox spirituality. God in his mercy will welcome back the repentant sinner. In the Sunday Liturgy one hears repeatedly: “Lord have mercy!” Orthodox Christians are en-couraged to cultivate a heart of repentance by saying repeatedly the Jesus Prayer: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.” Consistent attendance at the Sunday Liturgy will give one a growing awareness that God is not so much the stern judge as He is the merciful father waiting for the prodigal to return home.

Orthodoxy understands the Christian life as one of struggle, even holy warfare against the world, flesh and devil. Having been born to new life in Christ we are currently engaged in a daily struggle against the passions of the flesh, our fallen human nature. The Christian life is a repeated cycle of us walking, our falling flat on our faces, and our getting up again, etc. Therefore, an Orthodox Christian is not surprised by our falling into sin like the Young Man. Orthodox Christians do not agonize over our salvation, nor do we inquire into our eternally decreed election.

This emphasis on divine mercy lays the foundation for the Orthodox teaching on synergy – we freely co-operate with God in our salvation. This view lies somewhere between the extremes of Calvinism and Pelagianism. Unlike the Pelagian heresy which assumed that man possessed the innate ability to live righteous lives, the Orthodox approach is that we need God’s grace given through the sacramental life of the Church. And unlike Calvinism which assumes that we are totally depraved and incapable of doing good unless God acts on us, we have the capacity to respond to God’s invitation to enter into his kingdom.

We avail ourselves of God’s grace in the Mysteries (sacraments) of the Church. The church services in combination with the spiritual disciplines prescribed by the Church comprise a therapeutic regimen designed to restore us to spiritual health. Through them we learn to pray, to be still before God, to deny the passions of the flesh, to acquire wisdom, in short we attain “the whole measure of the fullness of Christ” (Ephesians 4:13). This is not works righteousness but rather a synergistic process in which we are transformed by the Holy Spirit into the likeness of Christ.

We begin our Christian life with a wounded heart but over time through our following the Orthodox way of life, our hearts become stronger, more rational, and purified. Kallistos Ware wrote in The Orthodox Way:

The first stage, the practice of the virtues, begins with repentance. The baptized Christian, by listening to his conscience and by exerting the power of his free will, struggles with God’s help to escape from enslavement to passionate impulses. By fulfilling the commandments, by growing in his awareness of right and wrong and by developing his sense of ‘ought’, gradually he attains purity of heart…. (p. 141)

Over time our struggle to follow God’s commandments becomes easier as we become accustomed to doing God’s will and putting aside the passions of the flesh. What was alien to our fallen nature becomes over time natural to our new nature in Christ.

Christian Discipleship and Eschatology

Orthodoxy views the Christian life as preparation for the inevitable encounter with Jesus Christ at the final judgment. The Orthodox understanding that there is a connection between our spiritual condition and our eternal destiny was echoed by CS Lewis in his essay “Weight of Glory.”

It is a serious thing to live in a society of possible gods and goddesses, to remember that the dullest and most uninteresting person you can talk to may one day be a creature which, if you say it now, you would be strongly tempted to worship, or else a horror and a corruption such as you now meet, if at all, only in a nightmare. All day long we are, in some degree, helping each other to one or other of these destinations.

Every day we make choices that lead us in one of two directions: towards God and his kingdom or away from God and into the darkness of hell. Every year just before Great Lent commences the Orthodox Church celebrates the Sunday of the Last Judgment in which the parable of the sheep and the goats is read out loud (Matthew 25:31-46). Unlike some Christian circles that devote considerable amount of time and energy into speculation about the end times, the Orthodox Church uses this parable to remind us that even the normal everyday acts of charity can have eternal consequences.

This preparation for the final judgment takes place not just on the Sunday of the Last Judgment but throughout the year. Every Sunday in the Completion Litany Orthodox Christians pray:

That we may live out our lives in peace and repentance, let us ask of the Lord.

Following that, we pray for:

A Christian end to our lives, peaceful, free of shame and suffering, and for a good defense before the dread judgment seat of Christ, let us ask.

We prepare for the final judgment by living lives of peace, repentance, and piety. Orthodox Christians also anticipate and prepare for the final judgment in the Morning Prayers. An excerpt from one Morning Prayer often used by the Orthodox reads:

When I am being judged, do not allow the hand of the prince of this world to take hold of me, to throw me, a sinner, into the depths of hell, but stand by me and be a savior and mediator to me. Have mercy, Lord, on my soul, defiled through the passions of this life, and receive her cleansed by penitence and confession, for you are blessed to the ages of ages. Amen. (Prayer of Saint Eustratios)

Our confidence is not in our good works but in the mercies of God. In anticipation of the final judgment we trust Christ to protect us from Satan’s accusations, to heal our souls, and to purify our hearts through the sacrament of confession.

The words “theosis” or “deification” are often used to explain the Orthodox understanding of salvation. What may strike inquiring Protestants as a bizarre concept is really another way of referring to becoming mature or perfect in Christ, that is, like Christ (II Peter 1:4, I John 3:2, Romans 8:29). The promise of the Christian life is not just the forgiveness of sins but the restoration of the imago dei within us. The Orthodox Church believes that our ongoing sanctification will culminate with our glorification at the Second Coming of Christ.

theology boxes by Naked Pastor

Theology Boxes We Live In

While the forensic understanding of salvation (the forgiveness of sins) can be found in both the Reformed and Orthodox traditions, the forensic paradigm is given pride of place in Reformed soteriology. The prominence of the penal atonement theory is such that it overshadows other paradigms of salvation. While Orthodoxy does accept the forensic understanding of salvation, it takes a broader and more inclusive approach. In addition to salvation as the forgiveness of sins, Orthodoxy also stresses salvation as the healing of the soul, denying the passions of the flesh, and militant resistance to the Devil.

Medical Paradigm. As a result of the Fall the human soul has become diseased and wounded. In the ESV translation of Jeremiah 17:9 we read: “The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately sick; who can understand it?” Jesus taught that the evil thoughts emerging from men’s hearts make them unclean (Mark 7:20-23). David in Psalm 51 prayed: “Create in me a pure heart, O God, and renew a steadfast spirit within me.” Thus, our salvation requires the restoring of our disordered inner state to the integrity and wholeness that God intended for us.

Icon – Good Samaritan by Marice

Jesus often described salvation using medical terms.

It is not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick. I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners. (Mark 2:17)

Probably the best known example of the medical paradigm is the parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:30-35). In this story a certain traveler fell into the hands of robbers who beat him and left him half dead. Later in the story the Good Samaritan came to the injured traveler, bandaged his wounds, poured oil and wine on the man’s wounds, then took him to an inn. The traveler falling into the hands of robbers can be understood as humanity falling into the clutches of the Devil and his demons who ravaged his soul. The Good Samaritan pouring oil and wine on the man’s wounds is a reference to the sacraments of baptism, chrismation, and the Eucharist. The inn is a reference to the church as a spiritual hospital. This picture of humanity as the victims overcome by demons and rescued by God’s mercy is quite different from the legal paradigm which depicts humanity as guilty criminals standing before a stern judge.

Metropolitan of Nafpaktos Hierotheos in Orthodox Spirituality noted that Protestants’ understanding of faith as theoretical acceptance of God’s revelation has resulted in the absence of the therapeutic approach (p. 28). He finds a similar lack in the Roman Catholic tradition:

In deed we cannot find in all of Latin tradition the equivalent of Orthodoxy’s therapeutic method. The nous [mind] is not spoken of; neither is it distinguished from reason. The darkened nous is not treated as a malady and the illumination of the nous as its cure. Some greatly publicised Latin texts are sentimental and go no further than sterile moralising (pp. 29-30).

Orthodoxy has a deeper understanding of salvation and the healing of our souls that I have not seen in Protestantism. Metropolitan Nafpaktos wrote:

What is healed first and foremost is a person’s heart, which constitutes the centre of his entire being. In other words, it is not just the visible signs of illness that are treated, but also the inner self, the heart. When a person’s nous is sick, it is dispersed and scattered among created things through the senses, and is identified with the rational faculty. This is why it must return to dwell within the heart, which is the work of Orthodox spirituality. The Orthodox Church is referred to as a Hospital, a place of healing for the soul, for this reason (pp. 98-99).

The Orthodox Church, however, does not just stress the necessity of healing; it also outlines the means by which it can be achieved. Because a person’s nous and heart are impure, he must pass successfully through the three stages of growth in the spiritual life: purification of the heart, illumination of the nous and deification. Orthodoxy is not like philosophy. It is more closely related to the applied sciences, particularly medicine (pp. 99).

The Strong Man Paradigm. The Calvinist paradigm assumes that failure to keep God’s law is the result of willful disobedience, not inability. To view sin as the condition of being willing but lacking the ability to keep God’s law – involuntary sin — is for Reformed Christians a contradiction of terms. The Orthodox understanding of sin is broader and subtle going beyond just conscious and willful forms of sin. Below is an excerpt from a pre-Communion prayer composed by John Chrysostom, a fourth century church father, which reflects a more complex understanding of sin:

Wherefore I pray thee: have mercy upon me and forgive my transgressions both voluntary or involuntary, of word and of deed, of knowledge or of ignorance; and make me worthy to partake without condemnation of Thine immaculate Mysteries, unto remission of my sins unto life everlasting. Amen. (Emphasis added.)

Orthodoxy does not assume like Protestantism that one already has the ability, that what is needed is needed is right understanding which comes from Bible reading and attentive listening to the pastor’s sermon. The Orthodox understanding of sin is that our will and soul have been weakened by the Fall. Our disordered inner state has resulted in our wills lacking the unhindered ability to control our bodies and our desires. Orthodox spirituality also takes into account the external reality of demonic forces.

Christus Victor

Orthodoxy recognizes that as a result of the Fall humanity has come under the dominion of Satan much like a young kid coming under the grip of the neighborhood bully. Jesus taught:

In fact, no one can enter a strong man’s house and carry off his possessions unless he first ties up the strong man. Then he can rob his house. (Mark 3:27, NIV)

Here Jesus is describing himself as the hero who breaks into a neighborhood bully’s house and rescues all the stolen goods from the bully’s house. When Adam and Eve listened to the Devil’s words and rejected God’s words they came under Satan’s domination. The human race remained in bondage to the Devil until Christ defeated him on the Cross. The Christus Victor motif is a prominent theme in the Orthodox celebration of Easter. Where Orthodoxy celebrates Christ resurrection as the decisive defeat of the Death and the Devil, Western Christianity puts the emphasis on Christ’s suffering on the Cross to atone for our sins. The principal problem in the Western paradigm is God’s wrath against sinners, not man as weakened wounded hostages in bondage to the Devil.

The Strong Man paradigm can be seen in the Orthodox approach to baptism in which one must renounce Satan three times then three times confess Jesus as Lord. This act of renunciation and confession is critical for our salvation. Christian conversion is not simply agreeing with some theological concepts which is characteristic of Protestantism, but faith as trust and submission to Christ. Through baptism our citizenship in the kingdom of God is restored and we come under Christ’s lordship and blessing.

The Christian Life as Transformation by Divine Grace

The overpowering desire alluded to by the Young Man was probably his sexual desires. Rather than view human sexuality in terms of behavior, Orthodoxy views human sexuality in terms of inner energies and thoughts that give rise to action. In the modern spiritual classic The Mountain of Silence, Fr. Maximos tells Kyriacos Markides how a life devoted to prayer can transform our sexual drive.

“Woe to those monks and nuns,” Father Maximos went on after we stopped laughing, “who shovel into their subconscious their sexual passions. In such a state they would tremble and sweat in the presence of the opposite sex. There is no spirituality in that. What happens, and what we aim at, is the transmutation of erotic energy from earthly attractions to God, the way human beings were in their primordial natural state.”

“Eros turns into agape,” I muttered.

“Right. Such persons love all human being without distinction to their sex. Such persons do not have much to do with what belongs to the after-the-Fall state of humanity. Do you understand? The love of God totally transforms human beings through Grace. (from Mountain of Silence p. 144)

Fr. Maximos described how authentic spirituality takes us beyond external legal righteousness that plagued the Pharisees (see Matthew 5:20).

“…and that’s why the saints are truly liberated in their very being. They are the freest people on earth. Once they reach that state they can never be affected by the sins of the world. They are not terrified by them. They are not human beings fortified behind their prejudices and repressions. You may go meet saints and tell them the most horrendous sins. They will not be touched in their innermost core. Persons who have repressed their passions will get angry, will get into the punishing mood. If you tell them that you committed some sinful act, they will become very upset and judgmental. They will become intolerant without a trace of compassion. Do you know why? Because they themselves are suffering. They have a lot of repressed emotions and anger inside them, a lot of repressed logismoi [thoughts]. Such persons are moralistic and pious, but they are not saints.” (from Mountain of Silence p. 145)

The Reformed tradition understands sanctification primarily as being accomplished by the Word and Spirit indwelling the believer enabling them to have victory over sinful desires (Westminster Confession of Faith Chapter XV, the Westminster Larger Catechism Q. 75; see also the Second Helvetic Confession Chapter IX). In comparing the Reformed tradition against the Orthodox tradition care must be taken not to reduce the Reformed doctrine of salvation to justification. The point I want to make is that Orthodoxy’s synergistic approach to salvation allows for a broader and more holistic approach to sanctification.

Summary

Part of Young Man’s problem was his theological box. The Calvinist paradigm of salvation rests on God’s exclusive love for his elect, the total incapacity of fallen humanity, and God’s inscrutable election. This has been consequential for the Calvinist approach to salvation and the Christian life. Reformed spirituality is characterized by intellectual rigor and self discipline reflecting its monergistic premise than Orthodoxy’s synergistic approach to the healing of the soul through the sacramental life of the Church. The Orthodox paradigm takes a broader and more holistic approach to the fallen human condition. Orthodoxy emphasizes the fact that God genuinely loves ALL mankind. God is ever merciful waiting for us to turn to him. Orthodoxy assumes a genuine volitional repentance to be foundational to Christian spirituality. It incorporates the purification of the heart and healing of the soul not often found in the Reformed tradition. One striking difference is that the Orthodox Tradition possesses a well defined set of spiritual disciplines it applies to its members. In comparison to the Reformed tradition of pastoral care and spiritual direction which is quite young and undeveloped, Orthodoxy draws on a far more ancient tradition of spiritual care. In the next blog I will be describing this system of spiritual disciplines available to the Orthodox priest and its importance for our sanctification.

Robert Arakaki

Coming Soon: Part (2 of 2) – The Orthodox Pastor’s Tool Box for Pastoral Care

Recent Comments