A Response to David W.T. Brattston’s “Incense in Ante-Nicene Christianity”

Dear Folks,

Burckhardtfan brought to my attention David W.T. Brattston’s “Incense in Ante-Nicene Christianity” which appeared in Churchman (vol. 117 no. 3) in 2003.

The article is basically an argument against the use of incense in Christian worship. Brattston opens his article with the bold assertion:

The ante-Nicene Christian documents that have come down to us indicate that ancient Christians did not use incense in their worship at so early a period.

Brattston pursues two lines of argument: (1) there is no evidence that the early Christians used incense and (2) the use of incense was expressly prohibited.

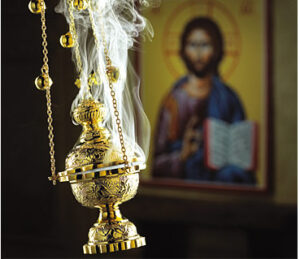

This is of interest to the OrthodoxBridge because incense is an integral part of Orthodox worship. Also, in several blog postings I have argued that the use of incense in Orthodox liturgy is a mark of right worship. In this blog posting I will assess the evidence cited by Brattston and present a defense for the use of incense in Orthodox worship.

Churchman is published by Church Society, a conservative evangelical Anglican organization. People associated with this group include: J.C. Ryle, Geoffrey Bromiley, J.I. Packer, and the late John Stott.

Note: Certain words in quoted texts have been emphasized for the convenience of the reader. Scripture passages are taken from the New International Version.

My Assessment

The first thing I noticed in looking over the article was that Brattston treats the data as if they were all of equal value. He arranges the data into the following categories: (1) Passing Comments, (2) Express Condemnations, (3) Absence of Expected Evidence, (4) Incense in Ante-Nicene Exegesis, and (5) The Exception. However, just because something was written long ago does not mean that it carries great weight. For example, Brattston mentioned Arnobius of Sicca as an early Christian who wrote extensively against the use of incense (p. 226). However, according to the New International Dictionary of the Christian Church (ed. J.D. Douglas), as a new convert Arnobius occasionally lapsed into unorthodoxy. Another source mentioned by Brattston is Tertullian. Because Tertullian is not regarded as a church father his writings need to be used judiciously.

The Orthodox approach is to give the greater weight to the witness of a bishop or a church council over that of a new convert or a theologian whose orthodoxy is in question. The witness of a bishop is given greater weight because the bishops are part of the apostolic succession and because they are responsible for the guarding of the Apostolic Tradition. With people of dubious standing like Tertullian or Origen the Orthodox approach is to cite them cautiously.

Another matter to consider is the context in which a statement about incense is made. There are several contexts we need to consider: (1) polemic against the use of incense in pagan worship, (2) polemic against the use of incense in hypocritical Jewish worship, and (3) polemic against the use of incense in Christian worship. By indiscriminately invoking numerous citations without regard for their context Brattston’s article can bamboozle readers unfamiliar with the church fathers. Therefore, it is urged that the reader take the time to read for themselves not just the passages cited, but also the overall context and background for that passage.

1. Passing Comments

The first source mentioned is Justin Martyr, a highly regarded second century Apologist who defended the Christian faith against the pagans. Justin opens his First Apology addressing the Roman emperor Titus with the fullest respect. He seeks to refute the accusation that the Christians were “atheists” due to their refusal to participate in the pagan rituals.

In Chapter 13 of his First Apology Justin writes:

What sober-minded man, then, will not acknowledge that we are not atheists, worshipping as we do the Maker of this universe, and declaring, as we have been taught, that He has no need of streams of blood and libations and incense; whom we praise to the utmost of our power by the exercise of prayer and thanksgiving for all things wherewith we are supplied, as we have been taught that the only honour that is worthy of Him is not to consume by fire what He has brought into being for our sustenance, but to use it for ourselves and those who need, and with gratitude to Him to offer thanks by invocations and hymns. (First Apology 13)

The phrase “we are not atheists” tells us that Justin is refuting the offering up of incense to the pagan gods. This tells us that Brattston is taking Justin Martyr out of context. An appropriate context would be if Justin was criticizing incense in Christian worship, but there is no evidence of that.

The second source cited is Athenagoras. Like Justin Martyr, Athenagoras was a highly regarded second century Apologist who defended the Christian faith against the pagans. He opens his Legatio (Plea) by respectfully addressing the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius by his full name and title. Athenagoras’ opening remark for Chapter 13 makes clear the context:

But, as most of those who charge us with atheism, and that because they have not even the dreamiest conception of what God is, and are doltish and utterly unacquainted with natural and divine things….

Then he explains why Christians abstain from offering up animal sacrifices and incense with the pagans.

And first, as to our not sacrificing: the Framer and Father of this universe does not need blood, nor the odour of burnt-offerings, nor the fragrance of flowers and incense, forasmuch as He is Himself perfect fragrance, needing nothing either within or without…. (A Plea For The Christians 13)

Here again Brattston takes a passage out of context. A polemic against the use of incense in pagan worship does not carry over to the use of incense in Christian worship.

A third source is the Epistle of Barnabas, another highly regarded source. Unlike Justin and Athenagoras’ apologies which were directed to a pagan audience, this anonymous epistle was written for a Christian audience. Attentive reading of Chapter 2 shows that the author is arguing for the superiority of Christian worship over Old Testament worship.

For He hath made manifest to us by all the prophets that He wanteth neither sacrifices nor whole burnt offerings nor oblations, saying at one time; What to Me is the multitude of your sacrifices, saith the Lord I am full of whole burnt-offerings, and the fat of lambs and the blood of bulls and of goats desire not, not though ye should come to be seen of Me. or who required these things at your hands? Ye shall continue no more to tread My court. If ye bring fine flour, it is in vain; incense is an abomination to Me; you new moons and your Sabbaths I cannot away with. These things therefore He annulled, that the new law of our Lord Jesus Christ, being free from the yoke of constraint, might have its oblation not made by human hands. (Epistle of Barnabas Chapter 2)

The Old Testament prophets’ denunciation of animal sacrifices and incense are not to be taken as a total rejection of Old Testament worship, but rather as a denunciation of hypocritical worship. While good, the Old Testament worship was limited and for that reason was superseded by worship under the New Covenant founded by Christ. The closing line for the excerpt above notes that the old was annulled so that new might come. Thus, the Epistle of Barnabas, while it mentions incense, does not criticize the use of incense in connection with Christian worship but in connection with the hypocrisy that plagued Old Testament worship.

Brattston cites his sources chronologically. Moving from early sources to the year 300 he cites Lactantius, a Christian historian and apologist who wrote Divine Institutes for the purpose of demonstrating Christianity’s superiority over paganism. The Catholic Encyclopedia gave a mixed review of this work noting: “The strengths and the weakness of Lactantius are nowhere better shown than in his work. The beauty of the style, the choice and aptness of the terminology, cannot hide the author’s lack of grasp on Christian principles and his almost utter ignorance of Scripture.”

Lactantius wrote in Divine Institutes 6.25:

Also in that perfect discourse, when he heard Asclepius inquiring from his son whether it pleased him that incense and other odours for divine sacrifices were offered to his father, exclaimed: “Speak words of good omen, O Asclepius. For it is the greatest impiety to entertain any such thought concerning that being of pre-eminent goodness. For these things, and things resembling these, are not adapted to Him. For He is full of all things, as many as exist, and He has need of nothing at all. But let us give Him thanks, and adore Him.”

What is interesting about this passage is Lactantius invoking a pagan source to criticize the use of incense in pagan worship. Here Brattston again takes a passage out of context.

Rounding out Brattston’s fourth century sources is Eusebius of Caesarea’s Demonstratio Evangelica. Eusebius is famous for his Church History which is the earliest surviving history of Christianity. His Demonstratio Evangelica is a defense of the Christian Gospel against pagan worship. The word “incense” appears eleven times in Book 1 Chapters 6, 7, and 10, and four times in Book 3 Chapters 1, 3, and 6.

Brattston notes that in Demonstratio Evangelica Book 1 Chapter 6 incense is understood to symbolize Christian prayer.

Malachi as well contends against those of the circumcision, and speaks on behalf of the Gentiles, when he says:

“10. I have no pleasure (in you), saith the Lord Almighty, and I will not accept a sacrifice at your hands. 11. For from the rising of the sun even to the setting my name has been glorified among the Gentiles; and in every place incense is offered to my name, and a pure offering.”

By “the incense and offering to be offered to God in every place,” what else can he mean, but that no longer in Jerusalem nor exclusively in that (sacred) place, but in every land and among all nations they will offer to the Supreme God the, incense of prayer and the sacrifice called “pure,” because it is not a sacrifice of blood but of good works? (Demonstratio Evangelica Book 1 Chapter 6)

That incense is a symbol of our prayers to God is something an Orthodox Christian would readily agree with. However, this does not rule out the use of incense in Christian worship.

In Demonstratio Evangelica Book 3 Chapter 3 incense is referred to in connection with pagan worship. Eusebius argues that without pure motives and elevated thoughts worship was just empty rituals.

But let me now examine the third point—-whether this is the reason why they call Him a deceiver, viz. that He has not ordained that God should be honoured with sacrifices of bulls or the slaughter of unreasoning beasts, or by blood, or fire, or by incense made of earthly things. That He thought these things low and earthly and quite unworthy of the immortal nature, and judged the most acceptable and sweetest sacrifice to God to be the keeping of His own commandments. That He taught that men purified by them in body and soul, and adorned with a pure mind and holy doctrines would best reproduce the likeness of God, saying expressly: “Be ye perfect, as your Father is perfect.” (Demonstratio Evangelica 3.3)

In Demonstratio Evangelica Book 3 Chapter 6 incense was mentioned in connection with pagan magic rituals, not with Christian worship.

And the disciples, who were with Him from the beginning, with those who inherited their mode of life afterwards, are to such an incalculable extent removed from base and evil suspicion (of sorcery), that they will not allow their sick even to do what is exceedingly common with non-Christians, to make use of charms written on leaves or amulets, or to pay attention to those promising to soothe them with songs of enchantment, or to procure ease for their pains by burning incense made of roots and herbs, or anything else of the kind. (Demonstratio Evangelica Book 3 Chapter 6)

In such wise I will conclude this part of the subject. But I must again attack my opposer, and inquire if he has ever seen or heard of sorcerers and enchanters doing their sorcery without libations, incense, and the invocation and presence of daemons. (Demonstratio Evangelica Book 3 Chapter 6)

What is surprising is the fact that Eusebius’ commentary on Malachi in Demonstratio Evangelica Book 1 Chapter 10 supports the Orthodox understanding of worship.

And so all these predictions of immemorial prophecy are being fulfilled at this present time through the teaching of our Saviour among all nations. Truth bears witness with the prophetic voice with which God, rejecting the Mosaic sacrifices, foretells that the future lies with us:

“Wherefore from the rising of the sun unto the setting my name shall be glorified among the nations. And in every place incense shall be offered to my name, and a pure offering.”

We sacrifice, therefore, to Almighty God a sacrifice of praise. We sacrifice the divine and holy and sacred offering. We sacrifice anew according to the new covenant the pure sacrifice. But the sacrifice to God is called “a contrite heart.” “A humble and a contrite heart thou wilt not despise. “Yes, and we offer the incense of the prophet, in every place bringing to Him the sweet-smelling fruit of the sincere Word of God, offering it in our prayers to Him. This yet another prophet teaches, who says: “Let my prayer be as incense in thy sight.”

So, then, we sacrifice and offer incense: On the one hand when we celebrate the Memorial of His great Sacrifice according to the Mysteries He delivered to us, and bring to God the Eucharist for our salvation with holy hymns and prayers; while on the other we consecrate ourselves to Him alone and to the Word His High Priest, devoted to Him in body and soul. Therefore we are careful to keep our bodies pure and undefiled from all evil, and we bring our hearts purified from every passion and stain of sin, and worship Him with sincere thoughts, real intention, and true beliefs. For these are more acceptable to Him, so we are taught, than a multitude of sacrifices offered with blood and smoke and fat.

Eusebius’ concluding line: “So, then, we sacrifice and offer incense….” contradicts Brattston’s argument. In fact, it articulates the Orthodox understanding that true worship must originate from the fear of God and love of one’s neighbors. The Eucharistic sacrifice is an expression of our love for God without which the liturgy would be empty rituals deserving divine condemnation.

Summary: A review of the evidence for the first section fails to support Brattston’s argument against the use of incense in Christian worship. Justin Martyr, Athenagoras, Lactantius, and Eusebius wrote against the use of incense in pagan worship. The Epistle of Barnabas criticized incense being used in hypocritical Old Testament worship. And surprisingly, one of Brattston’s sources, Eusebius of Caesarea, wrote favorably about the use of incense in worship.

2. Express Condemnation

Justin Martyr’s Second Apology was addressed to the Roman Senate for the purpose of refuting the false accusations against the Christians, e.g., cannibalism and immorality. In chapter 5 he describes how the demons led the human race into idolatrous worship and through the offering of libations and incense to the idols. Thus, the expressed condemnation here is in connection with pagan worship, not Christian worship.

The next source Brattston cites is Tertullian, a contentious second century apologist. However, his reputation for theological brilliance must be considered against his later deviations. The question here is: Did Tertullian condemn the use of incense in Christian worship? Brattston’s first citation is Tertullian’s Apology 42 in which he criticizes the burial custom of using frankincense to cover up the smell of the dead body. In Apology 30 Tertullian informs the Roman rulers that the Christian offer prayers on their behalf in the manner of the Christians, not the pagans.

Without ceasing, for all our emperors we offer prayer. We pray for life prolonged; for security to the empire; for protection to the imperial house; for brave armies, a faithful senate, a virtuous people, the world at rest, whatever, as man or Cæsar, an emperor would wish. These things I cannot ask from any but the God from whom I know I shall obtain them, both because He alone bestows them and because I have claims upon Him for their gift, as being a servant of His, rendering homage to Him alone, persecuted for His doctrine, offering to Him, at His own requirement, that costly and noble sacrifices of prayer dispatched from the chaste body, an unstained soul, a sanctified spirit, not the few grains of incense a farthing buys — tears of an Arabian tree—not a few drops of wine,— not the blood of some worthless ox to which death is a relief, and, in addition to other offensive things, a polluted conscience, so that one wonders, when your victims are examined by these vile priests, why the examination is not rather of the sacrificers than the sacrifices. (Apology 30)

Tertullian is arguing that the Christians do indeed pray for the Roman emperor. But unlike the pagans who rely on the perfunctory gesture of a few grains of incense or a few drops of wine, the Christians offer up sincere prayers from their hearts.

Brattston cites Arnobius, a fourth century teacher of rhetoric who wrote Ad Nationes with the intent of exposing the fallacies of pagan worship. Brattston notes that Arnobius “wrote more about incense than all other ante-Nicene Christians combined” (p. 226). But sheer quantity is inadequate if it is not really relevant to the argument one is making. In the case of Arnobius Ad Nationes Book 7 Chapters 26 to 29 numerous references to the use of incense in connection with pagan worship.

We have now to say a few words about incense and wine, for these, too, are connected and mixed up with your ceremonies, and are used largely in your religious acts. (Against the Heathen Book 7.26)

It is clear from reading the passage and their context that Arnobius is attacking the use of incense in connection with pagan worship, not Christian worship.

Summary: A review of the evidence presented in the second section shows that what was condemned was the use of incense in pagan worship. None of the evidence presented here relates to Christian worship. Therefore, Brattston failed to make his argument in section two.

3. Absence of Expected Evidence

Brattston cites Pliny the Younger’s Letter 10.96, Justin Martyr’s First Apology 61, 65-67, and the Didache 8-10 all of which are excellent sources on early Christian worship. He expresses puzzlement over the silence on the use incense in early Christian worship. He takes the silence to mean that incense was not a part of early Christian worship. However, arguing from silence is very problematic, if that were the case.

However, I did find some positive evidence for the use of incense in the Ante-Nicene sources. Volume 7 of the Ante-Nicene Fathers series contains some of the early liturgies: the Liturgy of St. James, the Liturgy of St. Mark, and the Liturgy of Saints Addai and Mari. Because incense pertains to liturgical practices these constitute the most direct and authoritative witness among the Ante-Nicene sources.

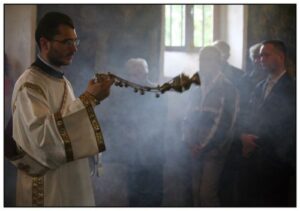

The Liturgy of St. James is the oldest Christian liturgy dating back to the first century church in Jerusalem. It is still in use in the Orthodox churches, being celebrated once a year on the feast day of St. James the Lord’s brother. This Liturgy contained 10 references to incense. It contained both rubrics for the priest and the prayers to be said out loud. For example,

Prayer of the incense at the beginning.

Sovereign Lord Jesus Christ, O Word of God, who didst freely offer Thyself a blameless sacrifice upon the cross to God even the Father, the coal of double nature, that didst touch the lips of the prophet with the tongs, and didst take away his sins, touch also the hearts of us sinners, and purify us from every stain, and present us holy beside Thy holy altar, that we may offer Thee a sacrifice of praise: and accept from us, Thy unprofitable servants, this incense as an odour of a sweet smell, and make fragrant the evil odour of our soul and body, and purify us with the sanctifying power of Thy all-holy Spirit: for Thou alone art holy, who sanctifiest, and art communicated to the faithful; and glory becomes Thee, with Thy eternal Father, and Thy all-holy, and good, and quickening Spirit, now and ever, and to all eternity. Amen.

The Liturgy of St. Mark is used in the Patriarchate of Alexandria and among the Coptic churches as well. In the Liturgy of St. Mark are 11 occurrences of “incense.” It contained short prayers like the following:

Accept at Thy holy, heavenly, and reasonable altar, O Lord, the incense we offer in presence of Thy sacred glory.

What is striking about the Liturgy of St. Mark is the way Malachi’s prophecy is blended into the prayer of the Anaphora (Eucharistic offertory prayer):

We offer this reasonable and bloodless sacrifice, which all nations, from the rising to the setting of the sun, from the north and the south, present to Thee, O Lord; for great is Thy name among all peoples, and in all places are incense, sacrifice, and oblation offered to Thy holy name.

The Liturgy of the Blessed Apostles (composed by St. Adaeus and St. Maris, aka Addai and Mari) contains 5 references to incense. This liturgy dates back to the third century Edessa and is in use among the Syrian Christians. What is notable is that incense is mentioned in the liturgical rubrics for the priest, e.g., instructions for the priest to cense the congregation or the Eucharistic elements.

In addition to the three ancient liturgies is a passage in Eusebius’ Demonstratio Evangelica (Book 1 Chapter 10) which was apparently overlooked by Brattston, and Canon 3 of the Apostolic Canons which will be discussed below. Taken together these form a massive and powerful witness to the use of incense in the Ante-Nicene Church.

Summary: Brattston’s failure to take into account the ancient liturgies of St. Mark, St. James, and Ss. Addai and Mari constitutes a fatal flaw to his argument that there is no evidence in support of incense in Ante-Nicene Christianity. This failure is all the more puzzling in light of the fact that the Ante-Nicene Fathers Series is easily accessible to the public.

4. Incense in Ante-Nicene Exegesis

One of the strongest arguments for the use of incense in Christian worship can be made from the Old Testament. Rather than give a balanced overview of the biblical evidence in support of incense in Old Testament worship and in opposition, Brattston focuses on Old Testament passages critical of the use of incense. It is important to keep in mind that Ante-Nicene Old Testament exegesis was influenced by the growing antagonism between Christianity and Judaism. So in reading the Ante-Nicene commentaries on Old Testament passages one must ask whether the writer’s motive was to critique the Jews’ worship practice or that of the Christians.

A balanced approach would have started off noting that incense was an integral part of Old Testament worship and was even commanded by God himself. This can be seen in Exodus 30:1 where Yahweh instructs Moses:

Make an altar of acacia wood for burning incense.

Incense was not an occasional feature of Old Testament worship but offered at least twice a day:

Aaron must burn fragrant incense on the altar every morning when he tends the lamps. He must burn incense again when he lights the lamps at twilight so incense will burn regularly before the Lord for the generations to come. (Exodus 30:7-8)

Incense was part of the historic pattern of Old Testament worship. It began under Moses, was continued during the time of the prophet Samuel (1 Samuel 2:28), King David (1 Chronicles 28:18), then King Solomon (2 Chronicles 2:4). By the time of Isaiah the prophet, the moral situation in Israel had deteriorated to the point that Temple worship had become a farce. This explains Isaiah’s sharp denunciation: “Your incense is detestable to me.” (Isaiah 1:13) John the Baptist’s father, Zechariah, was offering incense in the Temple when the angel Gabriel appeared to him (Luke 1:8-11). In this passage there is no hint of criticism about the use of incense.

As far as the spiritual significance of incense, I would fully concur with that. But would that be an argument against incense?

As far as the Epistle of Barnabas 2:4-5 and Isaiah 1:13 are concerned the divine judgment is not directed against the offering of incense and animal sacrifices but the hypocritical use of them. It would be like a husband who is cheating on his wife bringing home an extra nice bouquet of roses as a sign of his ‘love’ for her. Because of his hypocrisy the sign of affection becomes highly offensive and repugnant.

Note: Brattston cites Malachi 1:33 but that chapter has only 14 verses. I find it disturbing that he makes a basic mistake like that and that the magazine editors did not catch the mistake.

Brattston discusses Irenaeus of Lyons’ interpretation of Malachi 1:11:

“My name will be great among the nations, from the rising to the setting of the sun. In every place incense and pure offerings will be brought to my name, because my name will be great among the nations,” says the Lord Almighty.

Irenaeus is regarded as one of the more important early church fathers. Brattston assumes that Irenaeus wanted to exclude incense from Christian worship, but he gives no evidence to support this assumption. An attentive reading of Against Heresies Book 4 Chapter 17 shows that Irenaeus wanted to prove the inadequacies of Jewish worship and the superiority of Christian worship. This can be seen first in the section heading: “Proof That God Did Not Appoint The Levitical Dispensation For His Own Sake, Or As Requiring Such Service; For He Does, In Fact, Need Nothing From Men.” Greater proof can be found by Irenaeus himself.

For from the rising of the sun, unto the going down [of the same], My name is glorified among the Gentiles, and in every place incense is offered to My name, and a pure sacrifice; for great is My name among the Gentiles, saith the Lord Omnipotent;”—indicating in the plainest manner, by these words, that the former people [the Jews] shall indeed cease to make offerings to God, but that in every place sacrifice shall be offered to Him, and that a pure one; and His name is glorified among the Gentiles.

The point Irenaeus is making here is for the superiority of Christian worship over Jewish worship. There is no evidence of the practice of offering up incense passing away with the old dispensation, rather Malachi foretells that incense would continue into the new dispensation.

In light of the absence of evidence that Irenaeus was trying to discourage Christians from using incense in Christian worship Brattston’s argument here falls flat.

Hippolytus of Rome, a highly regarded Christian theologian of the third century, is well known for his Apostolic Tradition. Brattston makes his argument from Hippolytus’ commentary on the highly allegorical Song of Songs and Blessing of Moses. Brattston argues: “From the extensive reference to literal incense in this Commentary [Song of Songs], we should expect at least one allusion to its use in Christian worship if it had a place there.” (p. 229) As noted earlier, arguing from silence is not a strong argument.

Another source Brattston relies on is Origen, the brilliant but erratic third century theologian. Because he held to questionable ideas like the pre-existence and transmigration of souls the Orthodox Church does not regard him as a Church Father. Apparently in his homilies on Leviticus, Origen seeks to provide a spiritual interpretation of the Old Testament in order to prove the superiority of Christianity over Judaism.

Brattston discusses the Apostolic Canons, a collection of decisions and rubrics governing life and worship in the early church. Its significance can be seen in the fact that it was endorsed by the Council in Trullo in 692. There is an interesting reference to incense in Canon 3 which supports the use of incense in the early liturgies:

If any bishop or presbyter offer any other things at the altar, besides that which the Lord ordained for the sacrifice, as honey, or milk, or strong-made drink instead of wine, [the text here varies] or birds, or any living things, or vegetables, besides that which is ordained, let him be deposed. Excepting only new ears of corn, and grapes at the suitable season. Neither is it allowed to bring anything else to the altar at the time of the holy oblation, excepting oil for the lamps, and incense.

Brattston notes that Hippolytus’ Apostolic Constitution contradicts the Apostolic Canons stricture on the bringing of milk and honey to the Eucharistic table and from that inconsistency argues that the authority of these sources must be regarded of limited utility. While there may be some variation in early liturgical practices, the text before us appears to allow for incense in early Christian worship. If so, then this is another early witness to the use of incense in early Christian worship!

Summary: The prophetic denunciation of incense used in connection with hypocritical Old Testament worship does not constitute a prohibition against incense in Christian worship. Neither does the allegorical meaning of incense constitute a prohibition its use. Moreover, one of Brattston’s sources, Canon 3 of the Apostolic Canons, provides an early witness to the use of incense in early Christian worship!

5. The Exception

In the “Exception” Brattston draws on the Gnostic writing, the Second Book of Jeu/Jeux. Given the fact that it is a heretical document outside of the Christian mainstream, it has no place in the article. It would have been understandable if the author was doing a historical survey, but irresponsible or distracting if he is attempting to make a theological argument.

My Response

The first thing to note is that the Bible talks positively about the use of incense in the Old Testament Tabernacle (Exodus 30) and there is no indication of it being abolished in the new covenant. While the Old Testament prophets issued strong denunciations of hypocritical worship, in no way did they issue a blanket condemnation of incense.

The other is the prevalence of the practice among the historic churches. Incense is used occasionally at Roman Catholic Masses. It is a normal part of Orthodox worship. At a nearby Coptic Church I have seen the whole sanctuary become hazy with the smell of incense. The fact that these three ancient Christian traditions use incense in their liturgies provides a powerful witness to the antiquity and universality of incense in Christian worship. So when we juxtapose the current liturgical practices of these historic churches with the liturgical documents from the Ante-Nicene period we are confronted by antiquity and universality of incense in Christian worship. Applying the Vincentian Canon criteria of “everywhere, always, by all,” the case can be made that incense is part of the Great Tradition of the Church.

This leads to a theological method: lex orans, lex credens – the rule of prayer is the rule of belief. The way Roman Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, and the Oriental Orthodox Churches worship is a powerful support for the use of incense. Brattston’s method is to rely heavily on written texts. This is consistent with his training as a lawyer and with the Protestant theological method. But it is at odds with the way the early Church did theology. The early Church did not use the Protestant principle of sola scriptura. In the early centuries the biblical canon was still in flux. The early Church relied on the Tradition of the Apostles. Scripture was part of that Tradition, as well as an oral tradition concerning doctrines, worship practices, and holy living. All this came together in the weekly Eucharist where the Scriptures were read and exposited on.

Conclusion

Brattston made two arguments. First, he argued that there is no evidence that the early Christians used incense. But I found ample positive evidences that disprove this. Eusebius in Demonstratio Evangelica Book 1 Chapter 10 wrote: “So, then, we sacrifice and offer incense.” Furthermore, the liturgical rubrics found in Apostolic Canons Canon 3 allowed for incense to be brought to the altar. Even more significant is the fact that abundant references to the use of incense can be found in the ancient liturgies of St. James, St. Mark, and Ss. Addai and Mari. Second, Brattston argued that the use of incense was expressly prohibited by the early Christian writers. However, a review of the material shows that he took the writings out of context. The polemics against incense by early Christians were directed mostly at the use of incense in pagan worship. A few references were directed against the hypocrisy associated with Old Testament worship and written to show the superiority of Christian worship over Jewish worship. Brattston presented not a single shred of evidence of an early church father objecting to the use of incense in Christian worship.

Regretfully, this article is deeply flawed. Much of the sources were taken out of context or not relevant to the purpose of the article. In addition, Brattston argues from silence, a highly dubious form of argumentation. Even more distressing is the fact Brattston overlooked contrary evidence in the very sources he did cite.

The author’s note provided at the end of the article identifies David W.T. Brattston as an adjudicator (judge) of the Small Claims Court of Nova Scotia, Canada. His training is in the field of law, not church history or Christian theology. His mishandling of the patristic sources is painfully evident to anyone who reads the sources for themselves. His condensed style of writing makes the reader heavily reliant on Brattston’s characterization of the content and context. If there is one positive aspect of Brattston’s article it is his detailed references which made double checking his claims easy to do.

In closing, I believe that culpability for this article lies not so much with the author as with the editors of Churchman who should have vetted the article more diligently before irresponsibly publishing it. I call on the editors of Churchman to retract this poorly researched article which misleads and misinforms people about the early Church.

Why Incense Matters

Incense matters because it is a marker of right worship. The prophet Malachi made three predictions about the Messianic Age: (1) Yahweh’s Name would be glorified universally among the Gentiles, (2) pure sacrifices would be offered in Yahweh’s Name, and (3) incense would be offered up everywhere (1:11). This prophecy was fulfilled when Christ sent his Apostles to all nations (Matthew 28:19-20) and the Apostles celebrated the Liturgy (Acts 13:1-2).

Thus, incense connects Old Testament worship with Christian worship. Just as incense was part of Old Testament worship so too it was part of Christian worship. It has been a part of the historic Christian worship. However, this pattern began to unravel with the Protestant Reformation. While more traditional or liturgical Protestant churches still use incense, under the influence of Puritanism and low church Protestantism incense began to be neglected or denigrated. In recent years Protestants have become aware of the loss of their historic heritage. However, attempts by the ancient-future movement and emergent churches to appropriate elements of ancient liturgical worship like incense and liturgies fall short because these are add ons rather than rooted in their church tradition. The key question for Protestants is whether they are ready to return to the ancient paths of Christianity. The prophet Jeremiah declared:

Stand at the crossroads and look; Ask for the ancient paths, Ask where the good way is, and walk in it, And you will find rest for your souls. (Jeremiah 6:16)

For Protestants who feel they have lost their way, incense can serve as a marker guiding them back to the ancient paths of Christianity.

Robert Arakaki

Recent Comments