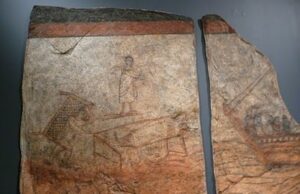

Healing of the Paralytic – Dura Europos c. AD 240

John Carpenter brought to my attention his article “Icons and the Eastern Orthodox Claim to Continuity with the Early Church” which was published in the Journal of the International Society of Christian Apologetics Vol. 6 No. 1 (April) 2013.

In it he attempts to refute the Orthodox position on icons by making the following points:

(1) The Orthodox Church claims “unbroken continuity” going back to the Apostles,

(2) The historical evidence shows that icons were not part of the early church, and

(3) Therefore, the Orthodox Church’s claim to “unbroken continuity” is disproved.

There are two basic components in Carpenter’s apologia: (1) the theological which challenge Orthodoxy’s claim to unbroken continuity and (2) the historical which consists of evidence that disprove early Christian usage of icons.

This posting will consist of three sub-sections: Part I which will be theological focusing on the nature of Tradition, Part II which will be historical focusing on the early usage of icons, and Part III which will assess Carpenter’s argument and offer my response to his challenge to Orthodoxy.

Part I. Theological Argument

Is Tradition Static?

John Carpenter understands continuity in Tradition to mean a static continuity that leaves no room for development and growth. In the introduction he writes:

But because Eastern Orthodoxy stakes its claim to legitimacy on “unbroken continuity” with the early church, any proof of significant departure of the Orthodox from the practices of the early church would undermine their claim. To defend their current prominent use of icons, the Orthodox have to assert that their iconography goes back to the Apostles. (p. 108)

Then in his conclusion, Carpenter writes:

A tradition, such as Catholicism, could handle this development by arguing that the church evolved under the direction of the Holy Spirit. But a tradition that stakes its claim on “unbroken continuity” must argue that Eusebius was in error; that he was a rare dissenting voice. But even that doesn’t dismiss the historical evidence that Eusebius’s argument (as well as Canon 36 of the Council of Elvira) constitutes. Even if one argues that Eusebius and Elvira were wrong and hold no authority, both show that, at least, significant leaders in the early church opposed icons. (p. 117)

What Rev. Carpenter wrote reflects a misunderstanding among Protestants as to how Orthodox Christians understand Tradition. This belief that Orthodoxy’s claim “unbroken continuity” leaves absolutely no allowance or room for any development has been a significant impediment to Reformed-Orthodox dialogue. Steven Bigham in Early Christian Attitudes toward Images (2004) counters that false characterization noting:

Few defenders of the idea of Tradition claim that nothing has changed since the beginning of the Church, and everyone recognizes that all the changes that have taken place have not necessarily been for the good. . . . . A healthy doctrine of Holy Tradition makes a place for changes, and even corruption and restoration, throughout history while still affirming an essential continuity and purity. This concept is otherwise known as indefectibility: the gates of hell will not prevail against the Church. This theoretical framework, indefectibility, takes change and evolution into account but denies that there has been or can be a rupture or corruption of Holy Tradition itself (p. 15; emphasis added).

Rev. Carpenter’s static understanding of Tradition raises all sorts of problems. By that definition then the Nicene Creed can be considered an innovative add on. Furthermore, it would imply that the term “Trinity”–which cannot be found in the Bible—can be considered a departure from Apostolic Tradition. Also, for the first several centuries the New Testament canon was an open question with some books included by some churches and other books left out by others. It was not until the Sixth Ecumenical Council formally defined the New Testament canon that the listing was formally closed. All this goes to show that there is an element of elaboration and development of doctrine and practice in early Christianity that does no violence to indefectibility or unbroken-continuity. Carpenter’s portrayal of the Orthodox understanding of Tradition as static is historically incorrect and leads him to set up a straw man argument.

II. The Historical Argument

Old Testament Sources

Artist depiction of Exodus 26:31

I was surprised that Rev. Carpenter overlooked one very important source of historical evidence: the Old Testament. The book of Exodus described the incorporation of two dimensional images of the cherubim on the Tabernacle walls and the entrance curtain to the Holy of Holies (Exodus 26). Images of the cherubim were also part of Solomon’s Temple (see 1 Kings 6, 2 Chronicles 3). It can be reasonably hypothesized that Herod’s Temple was adorned in similar fashion with images of the cherubim and other visual ornamentation. We read in Luke 21:5: “Some of his disciples were remarking about how the temple was adorned with beautiful stones and with gifts dedicated to God.” This lavish ornamentation was not an innovation introduced by Herod, but a tradition in Jewish worship going back to Moses. The Old Testament witness presents both a historical and theological justification for images in Jewish worship. Luke 21:5 suggests the continuation of the Jewish tradition of images in worship up to the time of Christ and the Apostles.

Rabbinical Sources

Another major weakness in Rev. Carpenter’s article is his skewed presentation of rabbinical writings. He failed to take into account the diversity among the Jews of Jesus’ time. He quotes extensively from rigorist rabbis who objected to any and all forms of images but left out or overlooked more moderate rabbis. For example we read in Abodah Zarah 33:

If it is a matter of certainty that [statues are] of kings [and hence made for worship], then all will have to concur that they are forbidden. If it is a matter of certainty [that the statues are] of local officials [and hence not for worship], then all will have to concur that they are [made merely for decoration and hence] permitted. (cited in Footnote 101 in Bigham p. 73)

Carpenter overstated the Jewish opposition to the use of images. He writes:

The commitment of second-temple Judaism to build a “fence” around the Second Commandment was such that Jews of the period protested the Roman flags with images and the profile of Caesar on the coins. (p. 110)

Denarius coin

Then what are we to make of Mark 12:13-17 where Jesus in a debate asked for a coin with Caesar’s image, held up the coin, and posed the question: “Whose portrait (εικων) is this?” It is clear from this passage that Jesus was not one of the rigorist rabbis, but held to a more moderate interpretation of the Second Commandment. But if we were to go by what Rev. Carpenter had written above then he would have to accuse Jesus of violating the Second Commandment! This puts Carpenter in an untenable position.

The Dog That Didn’t Bark or Arguing From Silence

After making his argument that no faithful Jew in the first century would have tolerated the use of images, Rev. Carpenter proceeds to argue that Christian iconoclasm can be proven by the absence of any vocal objections by other Jews. He writes:

Therefore, we can surmise that had the early church immediately adopted the use of icons in their meetings, there would have been vigorous denunciations from the traditional Jews. Given the heated controversy over circumcision and eating ceremonially unclean meat, surely an innovation involving Talmudic Judaism felt so strongly about as imagery in worship would have caused a heated debate that would have left some records (p. 110; emphasis added).

But we read in Abkat Rokel a quite different picture of early Judaism:

Indeed, curtains embroidered with figures are in use in almost every country where the Jews are scattered, without any fear of disturbing the thought of worshipers in the synagogue, for the reason that artistic decoration in honor of the Torah is regarded as appropriate and the worshiper, if disturbed by it, needs not observe the figures, as he can shut his eyes during prayer (Responsa #66, cited in Bigham p. 73; emphasis added).

John Carpenter’s argument reminds me about a Sherlock Holmes’ story about the dog that didn’t bark. It was initially thought that the dog’s failure to bark meant that no one had entered into the stable, but it later turned out that the dog did not bark because the perpetrator of the crime was the dog’s owner. So much for arguing from a silent dog! The point here is that the reason why there was no evidence of a ruckus over icons among first century Jews was because images were already in common use and widely accepted by early Jews.

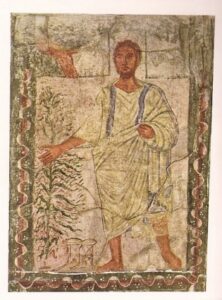

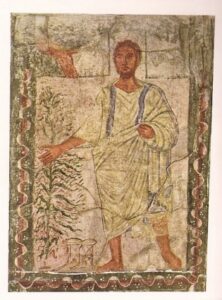

Moses and Burning Bush – Dura Europos. Source

One conspicuous evidence of early Jews being comfortable with the use of images in worship is the Dura-Europos synagogue. Archaeologists found on the walls of the ancient synagogue images of Abraham “sacrificing” Isaac, Moses receiving the Ten Commandments, Moses leading the Israelites out of Egypt, Ezekiel’s vision etc. I find it very puzzling that Rev. Carpenter knew of the Christian church in Dura-Europos but makes no mention of the synagogue in that same town! He dismisses Dura-Europos as a lone aberration but I would assert that it provides concrete proof of early accounts of images.

Carpenter’s failure to take into account of the Dura-Europos synagogue seriously weakens his article in two major ways. One, the synagogue gives us reason to believe that the introduction of icons was not due to Christian innovators but to Christians imitating their Jewish predecessors. Two, the presence of a Jewish synagogue in Dura-Europos solves the problem of the lack of Jewish brouhaha over the introduction of images. The solution is that there was no written record of a controversy because there was none in the first place. If the images found in the Dura-Europos were an extension of what was done at the Jerusalem Temple then there wouldn’t be any grounds for controversy. Much of the rigorist readings of the Second Commandment were in response to Jewish resentment of Roman rule in first century Palestine.

Steven Bigham in Early Christian Attitudes toward Images (2004) did a survey of early Jewish attitude toward images showing that the use of images was quite extensive among early Jews. (See my third review of Bigham’s book.) Andrew Louth in Greek East and Latin West (2007) noted that the aniconic Jewish synagogue was a later development, not something the early Christians would have been familiar with (p. 43).

Pagan and Early Christian Evidences

John Carpenter used the accusation of atheism by pagans as proof that the early Christians were aniconic. He writes:

Furthermore, early Christians (and sometimes Jews) were commonly called “atheists” by the Romans. They did so because the Christians (and Jews) did not have any images in their homes or churches and hence assumed that they had no gods at all (p. 111).

Using the pagan Romans’ perception of the early Christians to assess what was going on among the Christians is highly problematic. The pagans were outsiders with little or no understanding of the Faith.

Carpenter then cites a Christian source, Origen, but even then there are problems with using Origen to prove early iconoclasm. Origen wrote:

It is in consideration of these and many other such commands, that they [Christians] not only avoid temples, altars, and images, but are ready to suffer death when it is necessary, rather than debase by any such impiety the conception which they have of the Most High God (Contra Celsus 7.64 in Carpenter pp. 112-113).

The main problem is that that the context of this passage has to do with why Christians abstain from participating in pagan worship. There is no reference to how Christians in Origen’s time worshiped. In short, Carpenter mishandled his patristic sources. Carpenter’s unfamiliarity with patristic sources can be seen in his spelling “Origen” as “Origin.”

Eusebius of Caesarea

It is puzzling that Rev. Carpenter overlooked or ignored Eusebius the premiere early church historian. There are at least three passages that challenges Rev. Carpenter’s claim that the early Christians were aniconic or iconoclastic. We read in Eusebius’ Church History:

Nor is it strange that those of the Gentiles who of old, were benefited by our Saviour, should have done such things, since we have learned also that the likenesses of his apostles Paul and Peter, and of Christ himself, are preserved in paintings, the ancients being accustomed, as it is likely, according to a habit of the Gentiles, to pay this kind of honor indiscriminately to those regarded by them as deliverers (Church History 7.18; emphasis added)

It should be noted that Eusebius did not say that these portraits were used in churches. But they had to have been displayed somewhere. One possibility is that they were on display in the privacy of peoples’ home. If one takes into account that it was the wealthy who could afford to order the manufacture of these paintings of Christ and his Apostles and that the large homes owned by the wealthy were often where the Sunday worship services were held then it is not a stretch to hypothesize these portraits were used in the context of Christian worship.

If we link Eusebius’ comment with the archaeological findings of images on the walls of a Jewish synagogue and a Christian church in Dura-Europos then our hypothesis becomes more plausible and even more likely. The evidence does not say how the Christians related to these icons. Did the early Christians kiss them like the way Orthodox Christians do today? The evidence here is insufficient to answer the question. But the evidence does support the reasonableness of our hypothesis that it was not uncommon for Christians to have pictures of Christ and the Apostle on church walls and the untenability of Carpenter’s claim that the early Christians were aniconic.

There are other historical evidences by Eusebius that John Carpenter omits. One is Eusebius’ account of the statue of the healing of the woman with the issue of blood.

Eusebius writes:

For there stands upon an elevated stone, by the gates of her house, a brazen image of a woman kneeling, with her hands stretched out, as if she were praying. Opposite this is another upright image of a man, made of the same material, clothed decently in a double cloak, and extending his hand toward the woman (Church History 7.18, emphasis added).

In another account Eusebius describes in Proof of the Gospel the image of Abraham’s hospitality to the three visitors that could still be seen in his day.

And so it remains for us to own that it is the Word of God who in the preceding passage is regarded as divine: whence the place is even today honored by those who live in the neighborhood as a sacred place in Honor of those who appeared to Abraham, and the terebinth can still be seen there. For they who were entertained by Abraham, as represented in the picture, sit one on each side, and he in the midst surpasses them in Honor (The Proof of the Gospel 4.9 in Bigham pp. 210-211; emphasis added).

The one mention of Eusebius by Rev. Carpenter was Eusebius’ alleged letter to Emperor Constantine’s half-sister, Constantia. In the letter Constantia requests a picture of Christ and in reply he rebuffs her request on the ground that the true image of Christ could not be reduced to mortal flesh.

There are problems with this evidence proffered by Carpenter. One is that the letter is at odds with other writings by Eusebius that had a more positive tone with respect to Christian images. It is disturbing that Carpenter did not take into account the letter being inconsistent with the broader context of Eusebius’ literary career. Even more distressing is Carpenter’s failure to note the dispute among scholars surrounding Eusebius’ Letter to Constantia. Steven Bigham in Early Christian Attitudes toward Images devoted about 12 pages to a detailed discussion (Bigham pp. 193-206). This contrast sharply with Carpenter’s zero pages!

Even more disturbing is the theological argument found in the Letter to Constantia. Carpenter provides the reader with the following quote:

The flesh which He put on for our sake … was mingled with the glory of His divinity so that the mortal part was swallowed up by Life. . . . This was the splendor that Christ revealed in the transfiguration and which cannot be captured in human art. (citation in Carpenter p. 116; emphasis added)

What is disturbing about the theological rationale for Eusebius’ iconoclasm is that it is based upon the heresy of monophysitism: the false teaching that Christ’s divine nature swallowed up his human nature. By citing this letter and its theological rationale, Rev. Carpenter seems to have embraced a Christological heresy that was condemned by the Sixth Ecumenical Council. He should let us know where he stands on theological rationale given in the text above. If he does reject this heresy, then why would he want to use this letter?

Epiphanius of Salamis

Another early witness cited by Rev. Carpenter is Epiphanius, bishop of Salamis. This is an impressive witness because the Orthodox Church recognizes him as a saint. Also striking is the unmistakable iconoclastic language found in Epiphanius’ letter.

Moreover, I have heard that certain persons have this grievance against me: When I accompanied you to the holy place called Bethel, there to join you in celebrating the Collect, after the use of the Church, I came to a villa called Anablatha and, as I was passing, saw a lamp burning there. Asking what place it was, and learning it to be a church, I went in to pray, and found there a curtain hanging on the doors of the said church, dyed and embroidered. It bore an image either of Christ or of one of the saints; I do not rightly remember whose the image was. Seeing this, and being loth that an image of a man should be hung up in Christ’s church contrary to the teaching of the Scriptures, I tore it asunder and advised the custodians of the place to use it as a winding sheet for some poor person. They, however, murmured, and said that if I made up my mind to tear it, it was only fair that I should give them another curtain in its place. As soon as I heard this, I promised that I would give one, and said that I would send it at once. Since then there has been some little delay, due to the fact that I have been seeking a curtain of the best quality to give to them instead of the former one, and thought it right to send to Cyprus for one. I have now sent the best that I could find, and I beg that you will order the presbyter of the place to take the curtain which I have sent from the hands of the Reader, and that you will afterwards give directions that curtains of the other sort— opposed as they are to our religion— shall not be hung up in any church of Christ. A man of your uprightness should be careful to remove an occasion of offense unworthy alike of the Church of Christ and of those Christians who are committed to your charge. (in Jerome Letters 51)

The above paragraph is part of a long letter by Epiphanius to John, Bishop of Jerusalem. The main topic of the letter was Epiphanius’ forcible ordination of Jerome’s brother, Paulinian. The concluding iconoclastic paragraph was an apology or rather an apologia for his removal of curtains with images from a church in Bethel which was under Bishop John’s jurisdiction. One gets the sense that the Bishop of Salamis was like a bull in a china shop leaving havoc and hurt feelings in his wake.

In the debate about icons some have questioned the validity of Epiphanius’ letter. One is the Rev. Steven Bigham who wrote: Epiphanius of Salamis: Doctor of Iconoclasm? Deconstruction of a Myth. Leonid Ouspensky in Theology of the Icon noted that the bishops at the Seventh Ecumenical Council concluded that the iconoclastic letter attributed to Epiphanius were spurious on the grounds that while he was bishop there were churches on Cyprus that had been decorated with paintings (Ouspensky p. 131). Another well known Orthodox theologian, Georges Florovsky, in The Eastern Fathers of the Fourth Century considered the iconoclastic letters spurious (pp. 238-239). At the same time Florovsky noted that other sources considered genuine confirm Epiphanius’ aversion to visual images in church.

On the other hand, Jaroslav Pelikan in The Spirit of Eastern Christendom noted that even in modern times Epiphanius’ letters are still disputed, but he considered the iconoclastic treatises “probably genuine” (p. 102). Johannes Quasten in Patrology Vol. III noted that controversy surrounds the well known Letter 51, but that there are other sources that confirm Epiphanius’ opposition to images. Especially interesting is the letter to Emperor Theodosius I in which Epiphanius complained about his attempt to stop the making of images being ignored by his fellow bishops and mocked by the laity (Quasten p. 392).

Carpenter notes that he could not find any written evidence of an early church leader defending the use of images in church prior to the fifth century (p. 119). One possible reason is that images in church were part of the normal taken-for-granted practice. This is much like the way Protestants take for granted the presence of pews in their sanctuaries. The absence of written apologia for pews does not disprove the presence of pews in Protestant churches. Another possible reason is that Epiphanius’ opposition to images was viewed as a peculiarity and not a significant threat to the church. It was not until the eighth century that images and iconoclasm had become a major issue meriting not only written responses by Theodore the Studite and John of Damascus, but also a conciliar response, Nicea II. Part of the problem lies with Rev. Carpenter’s unrealistic expectations and his apparent unwillingness to work with sparse and ambiguous historical evidences. Another is that he is once again arguing from silence.

In terms of Rev. Carpenter’s fundamental argument that icons were not part of early Christian worship, Epiphanius as a witness is out of place. He was born in 315, just after Christianity became a legal religion, and died in 403, after the first two Ecumenical Councils. He can be viewed as a relatively late witness to iconoclasm, after Constantine. This does nothing to bolster Carpenter’s argument the early (pre-Constantine) Church was either aniconic or iconoclastic, but it does shed light on an important transition then taking place in Christian piety after Christianity became a public faith.

Council of Elvira

Another historical evidence cited by Rev. Carpenter against icons is the Council of Elvira which decreed:

Pictures are not to be placed in churches, so that they do not become objects of worship and veneration.

One thing I noticed was that the English translation given by Rev. Carpenter differed slightly from that given by Steven Bigham:

Placuit picturas in ecclesia esse non debere, ne quod colitur et adoratur in parietibus depingatur.

It has seemed good that images should not be in churches so that what is venerated and worshiped not be painted on the walls. (in Bigham p. 161)

There are problems with Rev. Carpenter’s translation of the Latin text. The literal translation of “parietibus depingatur” is “paint the walls” (passive voice). It is not clear where his rendering “placed in churches” come from. Bigham’s more literal translation allows for a more flexible and even ambiguous reading of Canon 36. Carpenter’s translation seems slanted so as to lock one into an iconoclastic reading. With respect to the Council of Elvira’s Canon 36, Steven Bigham notes that we don’t know of the immediate circumstances and that the canon may have been intended as a temporary restriction (Bigham 2004, p. 161 ff.). This problem is not apparent in Carpenter’s discussion of the text. See Gabe Martini’s discussion about the challenge of translating the Council of Elvira.

Good historiography calls for a careful handling of the evidence. In many instances scholars don’t know the immediate circumstance of a particular text or decision so they make educated guesses. In making guesses it is important that they use a tentative tone rather than a dogmatic tone. Carpenter on the other hand makes bold, unqualified statements. He writes:

The prohibition was against any images in the church buildings to forestall the danger of those images becoming icons. Hence, the 19 bishops at the Synod of Elvira were objecting to the presence of art in a church because of the temptation it presented; for example, they would object to our stained glass, saying that it had the potential to become idolatrous (p. 115).

There is so much we don’t know about the Council of Elvira and so little about what prompted Canon 36 that it is amazing to read Carpenter’s bold, audacious conclusion. This kind of bold language is something of a tradition in many Protestant fundamentalist circles, showing up in sermons or Sunday School lesson, but such dogmatism is completely out of place and inappropriate in a scholarly context, especially not in a refereed journal article!

Rev. Carpenter’s citing the Council of Elvira is something of a Protestant tradition that goes back to the Reformer John Calvin. In my article Calvin Versus the Icon I made the following assessment about Calvin’s handling of patristic literature:

However, in dealing with patristic literature it is not enough throw out names and councils as Calvin did. One must show how these references demonstrate a universal consensus among the church Fathers (i.e., Vincent of Lerins’ famous canon: “What has been believed everywhere, always and by all” Quod ubique, quod semper, quod ab omnibus). In the field of constitutional law the legal scholar’s strongest argument rests upon the findings of the Supreme Court, not the lower courts. Calvin’s references to one minor bishop (Epiphanius) or one local council (Elvira) or the polemical work sponsored by a king (Libri Carolini by Charlemagne) are all minor league stuff in comparison to the universal authority of an Ecumenical Council (Nicea II) and the reputation of highly respected church Fathers (John of Damascus and Theodore the Studite).

Carpenter’s handling of historical evidences and sources from early church fathers and church councils is much like amateur lawyers attempting to practice law before the Supreme Court. The American legal system consists of a network of hierarchies. We cannot pick and choose court decisions to live by; this will result in judicial anarchy! For Orthodoxy the Seven Ecumenical Councils have settled doctrinal controversies thereby restoring unity to the Church. Having ignored or outright rejected the Ecumenical Councils Protestant Christianity has become a confused cacophony of doctrines and creeds.

III. Assessment and Response

Assessment of Rev. Carpenter’s Argument

Rev. John B. Carpenter’s article fails to achieve its stated goal of repudiating the Orthodox use of icons. Here is a listing of problems I found in his article:

(1) Because he started out with a very flawed and faulty understanding of Orthodox tradition as static, Carpenter ended up constructing a straw man argument. If Rev. Carpenter disagrees with this claim then he must provide serious evidence showing that Orthodoxy understands Apostolic Tradition as static. Instead of simplistic Internet sources, Rev. Carpenter should draw on authoritative sources like an Orthodox hierarch (bishop), an early Church Father, or Ecumenical Council.

(2) His presentation of historical evidence is biased. His failure to include pro-icon accounts by Eusebius and early archaeological evidence suggests that he was not being fair in his consideration of the evidence. His relying solely on rigorist Jewish rabbinical sources and his ignoring moderate sources like Abkat Rokel raises serious questions about his scholarship.

(3) His historiography is amateurish. Unlike most historians who are willing to work with evidences that are sparse and at times ambiguous, Carpenter insists that the pro-icon side present irrefutable written evidence that early Christians venerated icons in the context of their worship services. The discipline of history is quite different from today’s courtroom where in a murder trial the prosecuting side must make an argument beyond a reasonable doubt. There were times when I thought Rev. Carpenter’s reasoning was more like a prosecuting attorney than a careful historian.

(4) His simplistic handling of early Christian sources weakens his argument. The Council of Elvira was an obscure minor council. One sign of a council’s importance is its being cited by others. But in the case of Elvira, it was soon forgotten until cited by the Protestant iconoclasts. It is telling that Elvira was not cited at the 754 iconoclast council. One minor council does not make for consensus of theological opinion. This leads to a related weakness in Carpenter’s approach. He failed to take into account the importance of consensus and conciliarity in the early Church. When a theological controversy surfaced among the early Christians there would be opposing sides. In time a unified consensus would be reached and affirmed by the Church catholic at an Ecumenical Council. For Rev. Carpenter to prefer the 754 iconoclast council over the Seventh Ecumenical Council of 787 shows his independent spirit and his independence from the one holy catholic and apostolic Church.

(5) So what are we to make of the anti-icon evidence presented by Carpenter? I would contend that in light of the broader context of the evidence presented in this posting that we see two things: (1) both early Judaism and early Christianity were quite accepting of images in worship and (2) there was a minority iconoclastic viewpoint among Jews and Christians. The iconoclastic view would come to dominate diaspora Judaism, while among the Christians it would be a minority view until its emergence as a significant movement in eighth century and its subsequent repudiation at the Seventh Ecumenical Council.

We Deserve Better

If there is to be fruitful dialogue between Protestants and Orthodox Christians on the issue of icons, it is important that both sides adhere to high academic standards. I was surprised that the issue of JISCA in which Carpenter’s article appeared did not list the authors’ background and credentials. From what I could find on the Internet, the Rev. Dr. John B. Carpenter is pastor of Covenant Reformed Baptist Church in Caswell County, North Carolina, and earned his Ph.D. at the Lutheran School of Theology in Chicago. Given Rev. Carpenter’s excellent education, it is disheartening that in his introduction he relied on Internet sources rather than the more widely accepted Orthodox authorities like an Orthodox hierarch (bishop), a Church Father, or an Ecumenical Council. As I read through John Carpenter’s article I was disturbed by his failure to interact with Orthodox sources like Jaroslav Pelikan’s Imago Dei and Leonid Ouspensky’s Theology of the Icon. And as noted earlier it is puzzling to find Carpenter leaving out critical evidence not favorable to his side. It is to be hoped that in the future the Rev. Carpenter will give us a more balanced and critically informed argument on icons.

A Challenge

Priest and Bishop at the Eucharist

Rev. Carpenter seems to be unfamiliar with the Orthodox understanding of capital “T” Tradition. Icons are indeed an integral part of Orthodox worship, but to say that they are “central” to Orthodox worship is laughable. What is central to the Divine Liturgy are the Gospel reading where we hear the words of Christ and the Eucharist where we receive Christ’s body and blood.

If Pastor Carpenter wishes to challenge Orthodoxy’s claim to unbroken apostolic continuity, he should marshal his arguments against two claims made by the Orthodox Church: (1) its claim to unbroken episcopal succession from the original Apostles to the present day and (2) its teaching of the real presence of Christ’s body and blood in the Eucharist. For Orthodoxy the episcopacy and the Eucharist form the core of Tradition. Icons, on the other hand, acquired dogmatic significance in the later centuries.

The significance of the episcopacy lies in the bishop as the official recipient and guardian of Apostolic Tradition. If Rev. Carpenter wishes to disprove Orthodoxy’s claim to apostolic continuity he needs to show how the early church was either congregational or presbyterian in polity and that the episcopacy was added on at a later date. But to do that he would need to take into account the very early witness to the episcopacy by Ignatius of Antioch who died 98/117.

Unlike Rev. Carpenter’s mistaken assertion that Orthodoxy “makes icons a central part of their liturgy and tradition” (p. 107), it is the Eucharist that is central to Orthodox worship. More specifically, it is the understanding that in the Eucharist we feed on Christ’s body and blood, a teaching that diverges from the memorialist understanding so widespread among Protestants and Evangelicals today. If Rev. Carpenter wishes to disprove Orthodoxy’s claim to apostolic continuity he needs to show how the early church held to a memorialist understanding of the Eucharist.

Robert Arakaki

In 2008, the Orthodox Study Bible was published by Thomas Nelson. Like the Geneva Bible, the Orthodox Study Bible has extensive commentary notes. Where it differs is that the commentary notes draw on the early Church Fathers. This is significant. The early Christians were admonished to hold fast to Apostolic Tradition both in written and oral forms (2 Thessalonians 2:15), and to ensure its transmission to future generations (2 Timothy 1:13, 2:2). This is the biblical basis for capital “T” Tradition. Because of the early Church Fathers’ proximity to the Apostles and their commitment to the traditioning process, we can be confident that the patristic exegesis of Scripture is faithful to the Apostle’s understanding of what Scripture meant. In contrast to this, the Geneva Bible draws on an exegetical tradition that date back to the 1500s, i.e., the Protestant Reformation. In other words, the commentary texts of the Geneva Bible ground the reader in a theological tradition that much more recent than that of the Church Fathers. It then becomes a question why one would prefer a four hundred year old tradition over another that is almost two thousand years old.

In 2008, the Orthodox Study Bible was published by Thomas Nelson. Like the Geneva Bible, the Orthodox Study Bible has extensive commentary notes. Where it differs is that the commentary notes draw on the early Church Fathers. This is significant. The early Christians were admonished to hold fast to Apostolic Tradition both in written and oral forms (2 Thessalonians 2:15), and to ensure its transmission to future generations (2 Timothy 1:13, 2:2). This is the biblical basis for capital “T” Tradition. Because of the early Church Fathers’ proximity to the Apostles and their commitment to the traditioning process, we can be confident that the patristic exegesis of Scripture is faithful to the Apostle’s understanding of what Scripture meant. In contrast to this, the Geneva Bible draws on an exegetical tradition that date back to the 1500s, i.e., the Protestant Reformation. In other words, the commentary texts of the Geneva Bible ground the reader in a theological tradition that much more recent than that of the Church Fathers. It then becomes a question why one would prefer a four hundred year old tradition over another that is almost two thousand years old.

Recent Comments