Folks,

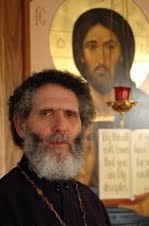

I am reposting Fr. James Bernstein’s excellent article about the history of the Bible and how what he learned caused him to abandon sola scriptura (the Bible alone) for the Bible in Tradition.

Robert

Source: “Which Came First: The Church or the New Testament?” by Fr. A. James Bernstein was published by Conciliar Press/Ancient Faith Publishing and is used by permission. All rights reserved. It is available in booklet form, along with many other booklets on topics of Orthodox faith and practice, at http://store.ancientfaith.com/booklets/

As a Jewish convert to Christ via evangelical Protestantism, I naturally wanted to know God better through the reading of the Scriptures. In fact, it had been through reading the Gospels in the “forbidden book” called the New Testament, at age sixteen, that I had come to believe in Jesus Christ as the Son of God and our promised Messiah. In my early years as a Christian, much of my religious education came from private Bible reading.

By the time I entered college, I had a pocket-sized version of the whole Bible that was my constant companion. I would commit favorite passages from the Scriptures to memory, and often quote them to myself in times of temptation-or to others as I sought to convince them of Christ. The Bible became for me-as it is to this day-the most important book in print. I can say from my heart with Saint Paul the Apostle,

“All Scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness” (2 Timothy 3:16).

That’s the good news!

The bad news is that often I would decide for myself what the Scriptures meant. For example, I became so enthusiastic about knowing Jesus as my close and personal friend that I thought my own awareness of Him was all I needed. So I would mark verses about Jesus with my yellow highlighter, but pass over passages concerning God the Father, or the Church, or baptism. I saw the Bible as a heavenly instruction manual. I didn’t think I needed the Church, except as a good place to make friends or to learn more about the Bible so I could be a better do-it-yourself Christian. I came to think that I could build my life, and the Church, by the Book. I mean, I took sola scriptura (“only the Bible”) seriously! Salvation history was clear to me: God sent His Son, together they sent the Holy Spirit, then came the New Testament to explain salvation, and finally the Church developed.

Close, maybe, but not close enough.

Let me hasten to say that the Bible is all God intends it to be. No problem with the Bible. The problem lay in the way I individualized it, subjecting it to my own personal interpretations-some not so bad, others not so good.

A STRUGGLE FOR UNDERSTANDING

It was not long after my conversion to Christianity that I found myself getting swept up in the tide of religious sectarianism, in which Christians would part ways over one issue after another. It seemed, for instance, that there were as many opinions on the Second Coming as there were people in the discussion. So we’d all appeal to the Scriptures.

“I believe in the Bible. If it’s not in the Bible I don’t believe it,”

became my war cry.

What I did not realize was that everyone else was saying the same thing! It was not the Bible, but each one’s private interpretation of it, that became our ultimate authority. In an age which highly exalts independence of thought and self-reliance, I was becoming my own pope! The guidelines I used in interpreting Scripture seemed simple enough: When the plain sense of Scripture makes common sense, seek no other sense. I believed that those who were truly faithful and honest in following this principle would achieve Christian unity.

To my surprise, this “common sense” approach led not to increased Christian clarity and unity, but rather to a spiritual free-for-all!

Those who most strongly adhered to believing “only the Bible” tended to become the, most factious, divisive, and combative of Christians-perhaps unintentionally. In fact, it seemed to me that the more one held to the Bible as the only source of spiritual authority, the more factious and sectarian one became. We would even argue heatedly over verses on love! Within my circle of Bible-believing friends, I witnessed a mini-explosion of sects and schismatic movements, each claiming to be “true to the Bible” and each in bitter conflict with the others. Serious conflict arose over every issue imaginable: charismatic gifts, interpretation of prophecy, the proper way to worship, communion, Church government, discipleship, discipline in the Church, morality, accountability, evangelism, social action, the relationship of faith and works, the role of women, and ecumenism. The list is endless. In fact any issue at all could-and often did-cause Christians to part ways.

The fruit of this sectarian spirit has been the creation of literally thousands of independent churches and denominations. As I myself became increasingly sectarian, my radicalism intensified, and I came to believe that all churches were unbiblical: to become a member of any church was to compromise the Faith. For me, “church” meant “the Bible, God, and me.” This hostility towards the churches fit in well with my Jewish background.

I naturally distrusted all churches because I felt they had betrayed the teachings of Christ by having participated in or passively ignored the persecution of the Jews throughout history. But the more sectarian I became-to the point of being obnoxious and antisocial-the more I began to realize that something was seriously wrong with my approach to Christianity. My spiritual life wasn’t working. Clearly, my privately held beliefs in the Bible and what it taught were leading me away from love and community with my fellow Christians, and therefore away from Christ. As Saint John the Evangelist wrote,

“He who does not love his brother whom he has seen, how can he love God whom he has not seen?” (1 John 4:20).

This division and hostility were not what had drawn me to Christ. And I knew the answer was not to deny the Faith or reject the Scriptures. Something had to change. Maybe it was me. I turned to a study of the history of the Church and the New Testament, hoping to shed some light on what my attitude toward the Church and the Bible should be. The results were not at all what I expected.

THE BIBLE OF THE APOSTLES

My initial attitude was that whatever was good enough for the Apostles would be good enough for me. This is where I got my first surprise. As I mentioned previously, I knew that the Apostle Paul regarded Scripture as being inspired by God (2 Timothy 3:16). But I had always assumed that the “Scripture” spoken of in this passage was the whole Bible-both the Old and New Testaments. In reality, there was no “New Testament” when this statement was made. Even the Old Testament was still in the process of formulation, for the Jews did not decide upon a definitive list or canon of Old Testament books until after the rise of Christianity. As I studied further, I discovered that the early Christians used a Greek translation of the Old Testament called the Septuagint.

This translation, which was begun in Alexandria, Egypt, in the third century B.C., contained an expanded canon which included a number of the so-called “deuterocanonical” (or “apocryphal”) books. Although there was some initial debate over these books, they were eventually received by Christians into the Old Testament canon. In reaction to the rise of Christianity, the Jews narrowed their canons and eventually excluded the deuterocanonical books-although they still regarded them as sacred. The modern Jewish canon was not rigidly fixed until the third century A.D.

Interestingly, it is this later version of the Jewish canon of the Old Testament, rather than the canon of early Christianity, that is followed by most modern Protestants today. When the Apostles lived and wrote, there was no New Testament and no finalized Old Testament.

The concept of “Scripture” was much less well-defined than I had envisioned.

EARLY CHRISTIAN WRITINGS

The second big surprise came when I realized that the first complete listing of New Testament books as we have them today did not appear until over 300 years after the death and resurrection of Christ. (The first complete listing was given by St. Athanasius in his Paschal Letter in A.D. 367.) Imagine it! If the writing of the New Testament had been begun at the same time as the U.S. Constitution, we wouldn’t see a final product until the year 2076! The four Gospels were written from thirty to sixty years after Jesus’ death and resurrection. In the interim, the Church relied on oral tradition-the accounts of eyewitnesses-as well as scattered pre-gospel documents (such as those quoted in 1 Timothy 3:16 and 2 Timothy 2:11-13) and written tradition.

Most churches only had parts of what was to become the New Testament.

As the eyewitnesses of Christ’s life and teachings began to die, the Apostles wrote as they were guided by the Holy Spirit, in order to preserve and solidify the scattered written and oral tradition. Because the Apostles expected Christ to return soon, it seems they did not have in mind that these gospel accounts and apostolic letters would in time be collected into a new Bible. During the first four centuries A.D. there was substantial disagreement over which books should be included in the canon of Scripture. The first person on record who tried to establish a New Testament canon was the second-century heretic, Marcion. He wanted the Church to reject its Jewish heritage, and therefore he dispensed with the Old Testament entirely. Marcion’s canon included only one gospel, which he himself edited, and ten of Paul’s epistles.

Sad but true, the first attempted New Testament was heretical. Many scholars believe that it was partly in reaction to this distorted canon of Marcion that the early Church determined to create a clearly defined canon of its own. The destruction of Jerusalem in A.D. 70, the breakup of the Jewish-Christian community there, and the threatened loss of continuity in the oral tradition probably also contributed to the sense of the urgent need for the Church to standardize the list of books Christians could rely on. During this period of the canon’s evolution, as previously noted, most churches had only a few, if any, of the apostolic writings available to them. The books of the Bible had to be painstakingly copied by hand, at great expense of time and effort. Also, because most people were illiterate, they could only be read by a privileged few. The exposure of most Christians to the Scriptures was confined to what they heard in the churches-the Law and Prophets, the Psalms, and some of the Apostles’ memoirs.

The persecution of Christians by the Roman Empire and the existence of many documents of non-apostolic origin further complicated the matter. This was my third surprise. Somehow I had naively envisioned every home and parish having a complete Old and New Testament from the very inception of the Church! It was difficult for me to imagine a church surviving and prospering without a complete New Testament. Yet unquestionably they did. This may have been my first clue that there was more to the total life of the Church than just the written Word.

THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO WHOM?

Next, I was surprised to discover that many “gospels” besides those of the New Testament canon were circulating in the first and second centuries. These included the Gospel according to the Hebrews, the Gospel according to the Egyptians, and the Gospel according to Peter, to name just a few. The New Testament itself speaks of the existence of such accounts. Saint Luke’s Gospel begins by saying,

“Inasmuch as many [italics added] have taken in hand to set in order a narrative of those things which have been fulfilled among us … it seemed good to me also … to write to you an orderly account” (Luke 1:1, 3).

At the time Luke wrote, Matthew and Mark were the only two canonical Gospels that had been written. In time, all but four Gospels were excluded from the New Testament canon. Yet in the early years of Christianity there was even a controversy over which of these four Gospels to use. Most of the Christians of Asia Minor used the Gospel of John rather than the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. Based upon the Passion account contained in John, most Christians in Asia Minor celebrated Easter on a different day from those in Rome. Roman Christians resisted the Gospel of John and instead used the other Gospels. The Western Church for a time hesitated to use the Gospel of John because the Gnostic heretics made use of it along with their own “secret gospels.” Another debate arose over the issue of whether there should be separate gospels or one single composite gospel account. In the second century, Tatian, who was Justin Martyr’s student, published a single composite “harmonized” gospel called the Diatessaron. The Syrian Church used this composite gospel in the second, third, and fourth centuries; they did not accept all four Gospels until the fifth century. They also ignored for a time the Epistles of John, 2 Peter, and the Book of Revelation. To further complicate matters, the Church of Egypt, as reflected in the second-century New Testament canon of Clement of Alexandria, included the “gospels” of the Hebrews, the Egyptians, and Mattathias. In addition they held to be of apostolic origin the First Epistle of Clement (Bishop of Rome), the Epistle of Barnabas, the Preaching of Peter, the Revelation of Peter, the Didache, the Protevangelium of James, the Acts of John, the Acts of Paul, and The Shepherd of Hermas (which they held to be especially inspired). Irenaeus (second century), martyred Bishop of Lyons in Gaul, included the Revelation of Peter in his canon.

OTHER CONTROVERSIAL BOOKS

My favorite New Testament book, the Epistle to the Hebrews, was clearly excluded in the Western Church in a number of listings from the second, third, and fourth centuries. Primarily due to the influence of Augustine upon certain North African councils, the Epistle to the Hebrews was finally accepted in the West by the end of the fourth century. On the other hand, the Book of Revelation, also known as the Apocalypse, written by the Apostle John, was not accepted in the Eastern Church for several centuries. Among Eastern authorities who rejected this book were Dionysius of Alexandria (third century), Eusebius (third century), Cyril of Jerusalem (fourth century), the Council of Laodicea (fourth century), John Chrysostom (fourth century), Theodore of Mopsuesta (fourth century), and Theodoret (fifth century). In addition, the original Syriac and Armenian versions of the New Testament omitted this book.

Many Greek New Testament manuscripts written before the ninth century do not contain the Apocalypse, and it is not used liturgically in the Eastern Church to this day. Athanasius supported the inclusion of the Apocalypse, and it is due primarily to his influence that it was eventually received into the New Testament canon in the East. The early Church actually seems to have made an internal compromise on the Apocalypse and Hebrews. The East would have excluded the Apocalypse from the canon, while the West would have done without Hebrews.

Simply put, each side agreed to accept the disputed book of the other. Interestingly, the sixteenth-century father of the Protestant Reformation, Martin Luther, held that the New Testament books should be “graded” and that some were more inspired than others (that there is a canon within the canon). Luther gave secondary rank to Hebrews, James, Jude, and Revelation, placing them at the end of his translation of the New Testament. Imagine-the man who gave us sola scriptura assumed the authority to edit the written Word of God!

THE NEW TESTAMENT MATURES

I was particularly interested in finding the oldest legitimate list of New Testament books. Some believe that the Muratorian Canon is the oldest, dating from the late second century. This canon excludes Hebrews, James, and the two Epistles of Peter, but includes the Apocalypse of Peter and the Wisdom of Solomon. It is not until A.D. 200-about 170 years after the death and resurrection of Christ-that we first see the term “New Testament” used, by Tertullian. Origen, who lived in the third century, is often considered to be the first systematic theologian (though he was often systematically wrong).

He questioned the authenticity of 2 Peter and 2 John. He also tells us, based on his extensive travels, that there were churches which refused to use 2 Timothy because the epistle speaks of a “secret” writing-the Book of Jannes and Jambres, derived from Jewish oral tradition (see 2 Timothy 3:8). The Book of Jude was also considered suspect by some because it includes a quotation from the apocryphal book, The Assumption of Moses, also derived from Jewish oral tradition (see Jude 9).

Moving into the fourth century, I discovered that Eusebius, Bishop of Caesarea and the “Father of Church History,” lists as disputed books James, Jude, 2 Peter, and 2 and 3 John. The Revelation of John he totally rejects. Codex Sinaiticus, the oldest complete New Testament manuscript we have today, was discovered in the Orthodox Christian monastery of Saint Catherine on Mount Sinai. It is dated as being from the fourth century and it contains all of the books we have in the modern New Testament, but also includes Barnabas and The Shepherd of Hermas.

During the fourth century, Emperor Constantine was frustrated by the controversy between Christians and Arians concerning the divinity of Christ. Because the New Testament had not yet been clearly defined, he pressed for a clearer defining and closing of the New Testament canon, in order to help resolve the conflict and bring religious unity to his divided Empire. However, as late as the fifth century the Codex Alexandrinus included 1 and 2 Clement, indicating that the disputes over the canon were still not everywhere firmly resolved.

WHO DECIDED?

With the passage of time the Church discerned which writings were truly apostolic and which were not. It was a prolonged struggle, taking place over several centuries. As part of the process of discernment, the Church met together several times in council. These various Church councils confronted a variety of issues, among which was the canon of Scripture. It is important to note that the purpose of these councils was to discern and confirm what was already generally accepted within the Church at large. The councils did not legislate the canon so much as set forth what had become self-evident truth and practice within the churches of God.

The councils sought to proclaim the common mind of the Church and to reflect the unanimity of faith, practice, and tradition as it already existed in the local churches represented. The councils provide us with specific records in which the Church spoke clearly and in unison as to what constitutes Scripture. Among the many councils that met during the first four centuries, two are particularly important in this context:

(1) The Council of Laodicea met in Asia Minor about A.D. 363. This is the first council which clearly listed the canonical books of the present Old and New Testaments, with the exception of the Apocalypse of Saint John. The Laodicean council stated that only the canonical books it listed should be read in church. Its decisions were widely accepted in the Eastern Church.

(2) The third Council of Carthage met in North Africa about A.D. 397. This council, attended by Augustine, provided a full list of the canonical books of both the Old and New Testaments. The twenty-seven books of the present-day New Testament were accepted as canonical. The council also held that these books should be read in the church as Divine Scripture to the exclusion of all others.

This Council was widely accepted as authoritative in the West.

THE BUBBLE BURSTS

As I delved deeper into my study of the history of the New Testament, I saw my previous misconceptions being demolished one by one. I understood now what should have been obvious all along: that the New Testament consisted of twenty-seven separate documents which, while certainly inspired by God nothing could shake me in that conviction-had been written and compiled by human beings. It was also clear that this work had not been accomplished by individuals working in isolation, but by the collective effort of all Christians everywhere-the Body of Christ, the Church. This realization forced me to deal with two more issues that my earlier prejudices had led me to avoid:

(1) the propriety and necessity of human involvement in the writing of Scripture; and

(2) the authority of the Church.

HUMAN AND DIVINE

Deeply committed, like many evangelicals, to belief in the inspiration of Scripture, I had understood the New Testament to be God’s Word only, and not man’s. I supposed the Apostles were told by God exactly what to write, much as a secretary takes down what is being dictated, without providing any personal contribution. Ultimately, my understanding of the inspiration of Scripture was clarified by the teaching of the Church regarding the Person of Christ. The Incarnate Word of God, our Lord Jesus Christ, is not only God but also man.

Christ is a single Person with two natures-divine and human. To de-emphasize Christ’s humanity leads to heresy. The ancient Church taught that the Incarnate Word was fully human-in fact, as human as it is possible to be-and yet without sin. In His humanity, the Incarnate Word was born, grew, and matured into manhood. I came to realize that this view of the Incarnate Word of God, the Logos, Jesus Christ, paralleled the early Christian view of the written Word of God, the Bible. The written Word of God reflects not only the divine thought, but a human contribution as well.

The Word of God conveys truth to us as written by men, conveying the thoughts, personalities, and even limitations and weaknesses of the writers-inspired by God, to be sure. This means that the human element in the Bible is not overwhelmed so as to be lost in the ocean of the divine. It became clearer to me that as Christ Himself was born, grew, and matured, so also did the written Word of God, the Bible. It did not come down whole-plop-from heaven, but was of human origin as well as divine. The Apostles did not merely inscribe the Scriptures as would a robot or a zombie, but freely cooperated with the will of God through the inspiration of the Holy Spirit.

A QUESTION OF AUTHORITY

The second issue I had to grapple with was even more difficult for me-the issue of Church authority. It was clear from my study that the Church had, in fact, determined which books composed the Scriptures; but still I wrestled mightily with the thought that the Church had been given this authority. Ultimately, it came down to a single issue. I already believed with all my heart that God spoke authoritatively through His written Word.

The written Word of God is concrete and tangible. I can touch the Bible and read it. But for some strange reason, I was reluctant to believe the same things about the Body of Christ, the Church-that she was visible and tangible, located physically on earth in history. The Church to me was essentially “mystical” and intangible, not identifiable with any specific earthly assembly. This view permitted me to see each Christian as being a church unto himself. How convenient this is, especially when doctrinal or personal problems arise!

Yet this view did not agree with the reality of what the Church was understood to be in the apostolic era. The New Testament is about real churches, not ethereal ones. Could I now accept the fact that God spoke authoritatively, not only through the Bible, but through His Church as well-the very Church which had produced, protected, and actively preserved the Scriptures I held so dear?

THE CHURCH OF THE NEW TESTAMENT

In the view of the earliest Christians, God spoke His Word not only to but through His Body, the Church. It was within His Body, the Church, that the Word was confirmed and established. Without question, the Scriptures were looked upon by early Christians as God’s active revelation of Himself to the world. At the same time, the Church was understood as the household of God,

“having been built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Jesus Christ Himself being the chief cornerstone, in whom the whole building, being fitted together, grows into a holy temple in the Lord” (Ephesians 2:20, 21).

God has His Word, but He also has His Body. The New Testament says:

(1) “Now you are the body of Christ, and members individually” (1 Corinthians 12:27; compare Romans 12:5).

(2)”He [Christ] is the head of the body, the church” (Colossians 1:18).

(3) ” And He [the Father] put all things under His [the Son’s] feet, and gave Him to be head overall things to the church, which is His body, the fullness of Him who fills all in all” (Ephesians 1:22, 23).

In early times there was no organic separation between Bible and Church, as we so often find today. The Body without the Word is without message, but the Word without the Body is without foundation. As Paul writes, the Body is

“the church of the living God, the pillar and ground of the truth” (1 Timothy 3:15).

The Church is the Living Body of the Incarnate Lord. The Apostle does not say that the New Testament is the pillar and ground of the truth. The Church is

the pillar and foundation of the truth

because the New Testament was built upon her life in God. In short, she wrote it! She is an integral part of the gospel message, and it is within the Church that the New Testament was written and preserved.

THE WORD OF GOD IN ORAL TRADITION

The Apostle Paul exhorts us, “Therefore, brethren, stand fast and hold the traditions which you were taught, whether by word or our epistle” (2 Thessalonians 2:15). This verse was one that I had not highlighted because it used two phrases I didn’t like: “hold the traditions” and “by word [of mouth].” These two phrases conflicted with my understanding of biblical authority. But then I began to understand: the same God who speaks to us through His written Word, the Bible, spoke also through the Apostles of Christ as they taught and preached in person. The Scriptures themselves teach in this passage (and others) that this oral tradition is what we are to keep! Written and oral tradition are not in conflict, but are parts of one whole. This explains why the Fathers teach that he who does not have the Church as his Mother does not have God as his Father. In coming to this realization, I concluded that I had grossly overreacted in rejecting oral Holy Tradition. In my hostility toward Jewish oral tradition, which rejected Christ, I had rejected Christian oral Holy Tradition, which expresses the life of the Holy Spirit in the Church. And I had rejected the idea that this Tradition enables us properly and fully to understand the Bible. Let me illustrate this point with an experience I had recently. I decided to build a shed behind my house. In preparation, I studied a book on carpentry that has “everything” in it. It’s full of pictures and diagrams, enough so that “even a kid could follow its instructions.” It explains itself, I was told. But, simple as it claimed to be, the more I read it, the more questions I had and the more confused I became. Disgusted at not being able to understand something that seemed so simple, I came to the conclusion that the book needed interpretation. Without help, I just couldn’t put it into practice. What I needed was someone with expertise who could explain the manual to me. Fortunately, I had a friend who was able to show me how the project should be completed. He knows because of oral tradition. An experienced carpenter taught him, and he in turn taught me. Written and oral tradition together got the job done.

WHICH CAME FIRST?

What confronted me at this point was the bottom line question: Which came first, the Church or the New Testament? I knew that the Incarnate Word of God, Jesus Christ, had called the Apostles, who in turn formed the nucleus of the Christian Church. I knew that the Eternal Word of God therefore preceded the Church and gave birth to the Church. When the Church heard the Incarnate Word of God and committed His Word to writing, she thereby participated with God in giving birth to the written Word, the New Testament. Thus it was the Church which gave birth to and preceded the New Testament. To the question, “Which came first, the Church or the New Testament?” the answer, both biblically and historically, is crystal clear.

Someone might protest,

“Does it really make any difference which came first? After all, the Bible contains everything that we need for salvation.”

The Bible is adequate for salvation in the sense that it contains the foundational material needed to establish us on the correct path. On the other hand, it is wrong to consider the Bible as being self-sufficient and self-interpreting. The Bible is meant to be read and understood by the illumination of God’s Holy Spirit within the life of the Church. Did not the Lord Himself tell His disciples, just prior to His crucifixion,

“When He, the Spirit of truth, has come, He will guide you into all truth; for He will not speak on His own authority, but whatever He hears He will speak; and He will tell you things to come” (John 16:13)?

He also said, “I will build My church, and the gates of Hades shall not prevail against it” (Matthew 16:18). Our Lord did not leave us with only a book to guide us. He left us with His Church. The Holy Spirit within the Church teaches us, and His teaching complements Scripture. How foolish to believe that God’s full illumination ceased after the New Testament books were written and did not resume until the Protestant Reformation in the sixteenth century, or-to take this argument to its logical conclusion-until the very moment when 1, myself, started reading the Bible. Either the Holy Spirit was in the Church throughout the centuries following the New Testament period, leading, teaching, and illuminating her in her understanding of the gospel message, or the Church has been left a spiritual orphan, with individual Christians independently interpreting-and often “authoritatively” teaching the same Scripture in radically different ways. Such chaos cannot be the will of God,

“for God is not the author of confusion but of peace” (1 Corinthians 14:33).

A TIME TO DECIDE

At this point in my studies, I felt I had to make a decision. If the Church was not just a tangent or a sidelight to the Scripture, but rather an active participant in its development and preservation, then it was time to reconcile my differences with her and abandon my prejudices. Rather than trying to judge the Church according to my modern preconceptions about what the Bible was saying, I needed to humble myself and come into union with the Church that produced the New Testament, and let her guide me into a proper understanding of Holy Scripture.

After carefully exploring various church bodies, I finally realized that, contrary to the beliefs of many modern Christians, the Church which produced the Bible is not dead. The Orthodox Church today has direct and clear historical continuity with the Church of the Apostles, and it preserves intact both the Scriptures and the Holy Tradition which enables us to interpret them properly. Once I understood this, I converted to Orthodoxy and began to experience the fullness of Christianity in a way I never had before.

Though he may have coined the slogan, the fact is that Luther himself did not practice sola scriptura. If he had, he’d have tossed out the Creeds and spent less time writing commentaries. The phrase came about as a result of the reformers’ struggles against the added human traditions of Romanism. Understandably, they wanted to be sure their faith was accurate according to New Testament standards. But to isolate the Scriptures from the Church, to deny 1500 years of history, is something the slogan sola scriptura and the Protestant Reformers-Luther, Calvin, and later Wesley-never intended to do.

To those who try to stand dogmatically on sola scriptura, in the process rejecting the Church which not only produced the New Testament, but also, through the guidance of the Holy Spirit, identified those books which compose the New Testament, I would say this: Study the history of the early Church and the development of the New Testament canon. Use source documents where possible. (It is amazing how some of the most “conservative” Bible scholars of the evangelical community turn into cynical and rationalistic liberals when discussing early Church history!)

Examine for yourself what happened to God’s people after the twenty-eighth chapter of the Book of Acts. You will find a list of helpful sources at the end of this booklet. If you examine the data and look with objectivity at what occurred in those early days, I think you will discover what I discovered. The life and work of God’s Church did not grind to a halt after the first century and start up again in the sixteenth. If it had, we would not possess the New Testament books which are so dear to every Christian believer.

The separation of Church and Bible which is so prevalent in much of today’s Christian world is a modern phenomenon. Early Christians made no such artificial distinctions. Once you have examined the data, I would encourage you to find out more about the historic Church which produced the New Testament, preserved it, and selected those books which would be part of its canon. Every Christian owes it to himself or herself to discover the Orthodox Christian Church and to understand its vital role in proclaiming God’s Word to our own generation.

SUGGESTED READING

Bruce, F.F., The Canon of Scripture, Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 1988.

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House, 1990.

Farmer, William R. & Farkasfalvy, Denis, The Formation of the New Testament Canon: An Ecumenical Approach, New York: Paulist Press, 1983.

Gamble, Harry Y., The New Testament Canon: Its Making and Meaning, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985.

Kesich, Veselin, The Gospel Image of Christ, Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1992.

Metzger, Bruce Manning, The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance, New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Meyendorff, John, Living Tradition, Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1978.

Histories of Christianity generally give some information on the formation of the Canon, although they are not likely to discuss its relevance to the authority and interpretation of Scripture.

Recent Comments