A Response to Protestant Criticisms

Today’s posting is by Eric Jobe. Eric has graciously given permission for his article which originally appeared on Orthodoxy and Heterodoxy to be reposted here. Source

Icon – Crucifixion

As Protestant Christians find their way to examining the Orthodox Christian faith, they very often remark about the inconsistency of Orthodox Christianity on the matter of justification by faith, or else they even say that Orthodoxy has no such doctrine of justification. Indeed, the term justification may be a bit curious to most Orthodox Christians who were not reared in Protestant homes, for one seldom encounters the term in Orthodox liturgy or theological discussion. It is perhaps most often encountered at the liturgical reading of the epistles of St. Paul or St. James, or perhaps one might recognize it from the service of baptism or chrismation. Yet these occurrences may pass notice and thus understanding.

But what of this notion of justification, and why should we pay heed to such criticisms made by Protestant observers of our Orthodox faith? A simple answer to this question might be that justification is a biblical doctrine, and it is one that has had a very significant impact in the history of Christianity. Nevertheless, the term justification has largely disappeared from Orthodox theological vocabulary, and this I would argue is for good reason.

A Changing Consensus

Critical scholarship over the last 50 years or so has begun to reassess the issue of justification in the epistles of St. Paul in conjunction with our ever-growing understanding of 1st century Judaism and its own understanding of what we could describe as “justification.” In the various sectarian theologies of Second Temple Judaism leading up to the time of Christ and the Apostles, Jews were very much concerned with who was in and who was out, i.e., who were the righteous before God and who were the wicked objects of His wrath. In order to maintain a position of being righteous before God, a pious Jew was expected to live in complete fidelity to Torah, the Law of Moses. The only question was, by whose interpretation of Torah should one live? The Jewish sect responsible for writing many of the Dead Sea Scrolls believed that they alone had received the correct interpretation of Torah, given to them by a man they called the Teacher of Righteousness, and all others were under the sway of the Wicked Priest or Man of the Lie, who had led them astray.

As the Gospel of Jesus Christ reached various Jewish communities throughout the Roman world, the question naturally rose as to what they should do about the Torah. Having believed in Messiah Jesus, should they still keep Torah? Furthermore, what should they do about Gentiles who came to believe in Messiah Jesus – should they become circumcised and follow Torah?

“. . . for by the works of the law shall no flesh be justified.” Galatians 2:16 KJV

Paul and James, Two Valid Perspectives

St. Paul’s answer to this question was decisive as well as ingenious, for he categorically denied that Jews or Gentiles were obligated to keep Torah, for they had been justified by faith apart from the works of Torah, such as circumcision and kosher dietary regulations. Furthermore, all had been baptized into one body, the Body of Jesus the Messiah, and had been given the gift of the Holy Spirit who would enable them to do what the Torah could not – to keep the righteous requirement of the Torah and live in obedience to God. To be baptized into the Messiah was to be baptized into His death and thus die to Torah to which they had previously been bound and to live unto Messiah Jesus by faith and the power of the Spirit.

St. James, on the other hand, likely felt that Paul had gone a bit too far in his jettisoning of the Torah, for he maintained that the Torah was still useful for instructing in righteousness, and that the works of Torah were to be understood simply as putting one’s faith into action. While Paul focused upon Torah as the means by which the Jews sought to establish their own imperfect righteousness before God, James saw the Torah as an efficient means by which one might live in obedience to God through faith. In spite of an apparent disagreement (which it was not in actuality, but only a difference in the use of terminology), it seems quite clear from both Paul and James that they agreed that both faith and obedience to God were necessary components of salvation, though they went about describing it in different ways.

The importance of all of this is to emphasize that justification is foremost an issue regarding the place of the Jewish Torah in the life of early Christian communities. For this reason, it is perhaps rightly de-emphasized in Orthodoxy, for we no longer have to deal with the same issues that the new Christian communities, composed of Jews and Gentiles seated at the same table, had to deal with.

Justification and Salvation

Justification is only one aspect of our salvation in Christ, which is manifold and comprehensive. Various aspects of this salvation have been emphasized in different eras or different geographic regions (i.e., East and West), but none can be exclusively claimed as the sole understanding of salvation. Let’s look at a few of these terms and ideas in order that we may parse out their connection and how they comprise a more comprehensive look at our salvation:

Justification – This term deals with how a person comes into and maintains a right relationship with God. Ultimately, this is made possible by the cross of Christ, by which He made expiation for our sins, granting us forgiveness and bringing us into a right relationship with God. Justification is accomplished at baptism and maintained through a life of obedience to God and confession of sins.

Sanctification – Sanctification is the process of separating a person or thing for exclusive use by God or for God. Holiness, the result of sanctification, is the state of being exclusively devoted to God. This ultimately requires purification from sin and detachment from the world and material things. This is usually seen as an ongoing process that one undergoes throughout one’s life. Sanctification is accomplished through ascetic struggle.

Glorification – The final state of Christians perfected in Christ after His Second Coming. While this term (as a participle) was used in Romans 8:29, Orthodoxy normally understands this idea to be the culmination of theosis (see below).

Adoption – The result of being engrafted into the Body of Christ through Baptism. We are adopted by God the Father as sons and co-heirs with Jesus Christ (Romans 8:15-17). Adoption is the state by which we may partake of the divine nature (2 Peter 1:4) through theosis (c.f. the series on theosis and adoption by Fr. Matthew Baker).

Faith – This term can be understood biblically in two senses: (Paul) trust, fidelity, or loyalty to Christ that includes obedience and good works, or (James) simple cognitive belief (James 2:19) that must be complemented with good works.

Works – Also, this term is used biblically in two senses: (Paul) the “works of the Torah” such as circumcision, kosher regulations, and the myriad of other ordinances of the Law of Moses that are incapable of establishing one as righteous before God, or (James) good works (in an ethical sense) and obedience before God which accompany genuine faith.

Theosis/Deification – Both the result of being adopted as sons and daughters of God through baptism into Christ and the process of attaining to the fulness of the divine nature and conformity to the image of Christ. The concept of theosis has the potential to be wildly misunderstood when it is taken away from its moorings in the concept of adoption and the sacramental life of the Church. If it is understood in a “mystical” or gnostic way as a spiritualized state of elite initiates or recipients of some special grace withheld from other baptized members of Christ’s Church, then we err from Patristic teaching on the matter.

Christus Victor – Literally “Christ the Victor” (IC XC NIKA), this concept is perhaps the most common expression of our salvation in Orthodox Christianity. It is most aptly characterized by the Paschal apolytikion: “Christ is risen from the dead trampling down death by death and upon those in the tombs bestowing life.” We are saved, because Christ has destroyed sin and death by His own death, and given life to us by His resurrection.

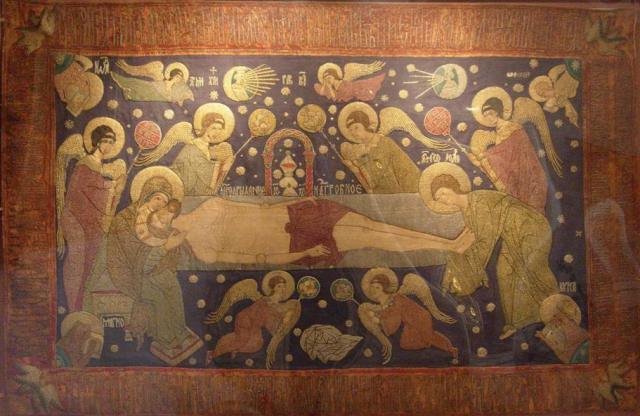

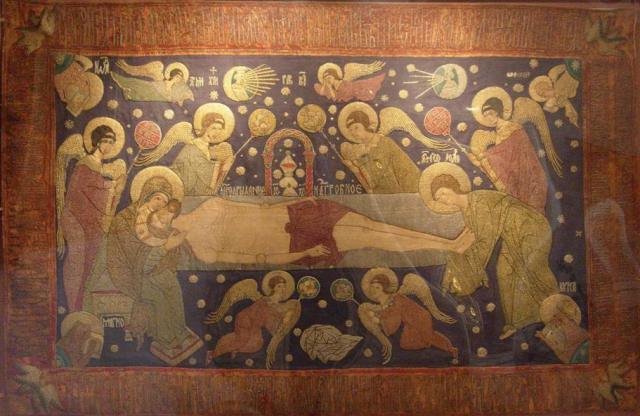

Tapestry of our Savior — Embroidered altar cloth – Yaroslav 16th century source

What to Take Away

• All of the above concepts are woven together to form the complete tapestry that is our salvation in Christ, and none of them alone can be exclusively made to be real essence of salvation to the virtual exclusion of the others.

• Justification is an important aspect of our salvation in Christ, though it is perhaps overemphasized in certain corners of Christianity. Justification is something that is inherently experienced and lived by every baptized Orthodox Christian, though it may be taken for granted.

• We should not allow early Christian disputes about the Law of Moses to cause us to stumble by creating false dichotomies between faith and works that do not take into account the various nuances given to these terms by biblical writers.

• Justification is wrongly set up as a singular touchstone of right doctrine, because it is only a part, not the whole of our salvation in Christ. As such, it cannot be considered the definitive aspect of soteriology (the doctrine of salvation) to the exclusion of other aspects of it.

• Justification is accomplished at baptism, the point where a person is granted forgiveness of sins and placed in a right relationship with God, and it is maintained through a life of obedience to God and confession of sins.

Justification accomplished at baptism source

As such, Orthodoxy does have a doctrine of justification, though it may not be explicitly referred to as such or emphasized as much as it is in certain Protestant communions. Orthodox Christians can confidently state that Orthodoxy does properly regard the biblical teaching of justification as being by faith apart from the works of the Torah, though faith is rightly understood as a life lived in faithful obedience to God. It is accomplished at baptism, the sacramental instrument by which sins are forgiven, and is maintained by confession of sins. Justification is integral to the life of every Orthodox Christian, and while we may not use the term quite so prominently as Protestant Christians, we nevertheless take it very seriously.

Eric Jobe is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at the University of Chicago. He specializes in Hebrew poetry, the Dead Sea Scrolls, and Second Temple Judaism. He is an instructor of Bible and biblical languages for the Orthodox Church in America, Diocese of the Midwest, Diaconal Vocations Program.

Recent Comments