Dominic Bnonn Tennant, a Reformed Baptist, raised some important questions about Reformed iconoclasm. In “Are Pictures of Jesus Idolatry?” he notes:

Thinking so is an understandably venerable Reformed tradition which strikes me as naive and legalistic on several levels. Here, I look at the context of the Second Commandment to exegete the limitation of its meaning.

The article has two-parts: Part 1: exegesis and Part 2: what were ancient people thinking. In the first part Tennant examines exegetical issues pertaining to the Second Commandment taking note of three issues.

1. The Second Commandment prohibits 3D objects, not flat 2D pictures.

The word “image” in the King James Version’s rendering “graven image” implies a flat picture, however, a more accurate translation would be the New American Standard Bible’s “idol.” It is worth noting that the Septuagint translation of the Second Commandment uses the Greek “ειδωλα (eidola),” not “εικον (eikon).” It seems that certain Protestant translations of the Bible have been slanted in a particular direction to suit a particular theological agenda.

Tennant notes that images of Jesus in a children’s’ picture bible are not carved and therefore not prohibited by the Second Commandment.

In other words, anyone who wants to say the commandment prohibits us from creating 2D pictures of Jesus needs to actually argue for that position. It is not a given. It isn’t as if the Hebrews couldn’t draw. The only given in the commandment itself, on the face of it, is that we cannot create carved or sculpted images. (Italics in original.)

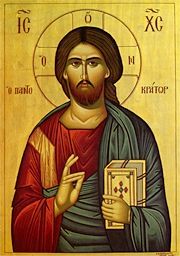

This line of reasoning can be used to justify Orthodox icons of Christ and also depictions of Christ in stained glass windows, a practice favored by Anglicans and Lutherans.

2. The Old Testament Has Directives About the Making of Carved Images.

One problem with Reformed iconoclasm is that a blanket prohibition against carved images would rule out the carved images like the cherubim over the Ark of the Covenant. Tennant notes: “If the second commandment includes a prohibition against any carved images, God would be contradicting himself (italics in original).”

3. Arguing from God’s invisibility is unbiblical and logically flawed.

Dominic Tennant notes that there are problems with arguing from God’s invisibility. First, God did in fact manifest himself in visible form several times in the Old Testament, e.g., to Abraham in Genesis 15-18, to Joshua in Joshua 5:13-15, and to Gideon in Judges 6.

Second, Tennant notes that in the Incarnation God revealed himself visibly in Jesus Christ. This has implications for the Second Commandment.

In any case, if we take Deuteronomy 4 as a touchstone for understanding the second commandment, it seems to blow any objection to images of Jesus out of the water. The whole covenantal, historical, revelational context of the second commandment is that God has not revealed himself in a created form—therefore, do not create an image of any created form to worship.

But this is simply no longer true! If this is the argument that justifies the second commandment, it is invalid under the new covenant, because God has now revealed himself in a created form: Jesus. (Emphases in original)

Here Dominic Tennant is reiterating John of Damascus’ classic apologia for icons:

When the invisible One becomes visible to flesh, you may then draw His likeness. When He who is bodiless and without form, immeasurable in the boundlessness of His own nature, existing in the form of God, empties Himself and takes the form of a servant in substance and in stature and is found in a body of flesh, then you may draw His image and show it to anyone willing to gaze upon it. (On Divine Images – First Apologia §8)

Tennant seems to be unaware of the classical defense of icons by one of the great church fathers of Ancient Christianity. Doing biblical exegesis in a historical vacuum carries the risk of being confined (unwittingly) to a particular reading of Scripture. The early Church Fathers’ exegesis of Scripture comprises a rich heritage for all Christians. A grounding in patristics will broaden Protestant pastors and theologians’ understanding of the biblical text and sharpen their understanding of theology.

Storm god – Bronze Age temple in Aleppo Syria. Kay Kohlmayer

What is Idolatry?

In Part 2, Dominic Tennant argues that to understand the Second Commandment we need to understand the nature of idolatry in ancient cultures. Ancient paganism was based on a monistic worldview in which the divine, human, and natural realms were ontologically identical with each other. This was the basis for sympathetic representation in which a representation was made of a natural element (storm, sky, rain, plant life) that could be controllable, i.e., manipulated towards certain ends (good harvest, clement weather, health). Tennant notes:

Idolatry entails (1) treating God and his creation as continuous, as through sympathetic representation; and/or (2) putting one’s faith in a divine being other than God.

Thus, the Second Commandment in its original context was not directed against the use of pictures in worship, or against Roman Catholicism as Reformed Christians seem to assume, but against idolatry as practiced by the Israelites’ neighbors in the ancient Near East. The intent behind the Second Commandment together with the First Commandment was right worship of the one true God.

He [Yahweh] does not want them trying to influence other deities; and he especially does not want them trying to influence him

Dominic Tennant and Orthodoxy

Is Tennant’s understanding of religious images compatible with Orthodoxy? In my opinion, he’s close but not quite. Tennant’s position is more in line with the Anglican or Lutheran traditions in Protestantism.

In terms of monism, a picture of Jesus is never—in evangelical circles—intended to “channel” or “center” Jesus or his power through something like sympathetic representation. (The same cannot be said for many Roman Catholic contexts.)

Missing from the above quote are: (1) an affirmation of the sacramental nature of icons and (2) the importance of venerating icons. In a later article “Are the first and second commandments morally distinguishable?” Tennant notes:

Of course, none of this has any bearing on pictures of Jesus in storybooks or memes, as neo-Puritans often shrilly claim. No Christian uses such pictures as aids to worship (that I know of!) Even in quite “Catholic” theological traditions, like the Lutherans and Anglicans, stained glass windows are nothing like idols. They exist to stimulate the mind to worship—I don’t think anyone worships through them in the way that they might kiss a photo of a relative. Mind you, kissing a photo is a bit weird too, in my opinion…

Here it is clear that Tennant remains a Protestant in his understanding of religious images. He sees their value in functional terms – “to stimulate the mind to worship.” His description of kissing a photo of a loved one pretty much describes how Orthodoxy understands the veneration of icons; his squeamishness about kissing icons reveals a very Protestant attitude!

In response to concerns that the Orthodox veneration of icons would mark a reversion to pagan monism, I would note that: (1) Orthodoxy’s sacramental worldview is grounded in the Incarnation—in Jesus Christ created matter is joined to the uncreated Word of God, and (2) the Bible gives examples of matter becoming channels of divine grace, e.g., the hem of Jesus’ cloak healing the woman with the issue of blood (Mark 5:27-30), Peter’s shadow having healing powers (Acts 5:15), and Elisha’s bones restoring a man to life (2 Kings 13:21).

Taken too far the separation of the divine and the natural realms which underlie the Reformed worldview can result in a naturalistic and destructive secularism. The Reformed disenchantment of the cosmos has robbed Christianity of the vibrant sacramental connection between material matter and the reality of heaven. It positions Reformed Christianity in modernity cut off from the sacramental worldview of the early Church.

Reformed Iconoclasm – Extreme and Untenable

Dominic Bnonn Tennant’s careful exegesis of the Second Commandment is a carefully staged demolition job on Reformed iconoclasm. He shows that the Reformed opposition to flat images goes beyond what the biblical text says about carved objects. His two-fold critique of the argument from God’s invisibility: (1) Old Testament accounts of God manifesting himself in visible form and (2) God taking on human flesh in the Incarnation, are biblically and theologically sound. They echo the classic apologia offered by the early Church Father, John of Damascus. Tennant’s observation that Reformed iconoclasm’s blanket opposition to carved images puts it at odds with other biblical passages that called for the making of carved objects like the cherubim is impressive. No Reformed Christian would dare admit that the Bible is self-contradictory! But will they reconcile the differences?

Tennant’s article is an invitation for Reformed pastors and theologians to critically examine the Reformed tradition’s opposition to icons. Failure to do so would result in Reformed iconoclasm becoming a manmade tradition! Tennant’s article also has the potential to advance Reformed-Orthodox dialogue. It is hoped that after reading Tennant’s articles Reformed Christians will examine the rich heritage of the early Church Fathers’ affirmation of icons.

Robert Arakaki

Recommended Reading

John of Damascus. Apologia Against Those Who Decry Holy Images.

Theodore the Studite. On Holy Icons.

Council of Nicea II (787). “The Decree of the Holy, Great, Ecumenical Synod, the Second of Nice.” NPNF Series II Vol. XIV The Seven Ecumenical Councils, pp. 549-551.

Robert Arakaki. 2011. “Calvin vs. the Icon: Was John Calvin Wrong?” OrthodoxBridge (19 June)

Robert Arakaki. 2011. “The Biblical Basis for Icons.” OrthodoxBridge (12 July)

Robert Arakaki. 2013. “Early Jewish Attitudes Toward Images.” OrthodoxBridge (29 July)

Vncent Gabriel. 2014. “St. Theodore the Studite against the Iconoclasts.” On Behalf of All (27 April)

Dominic Bnonn Tennant. 2014. “Are pictures of Jesus idolatry? – Part 1: exegesis.” (9 July)

Dominic Bnonn Tennant. 2015. “Are pictures of Jesus idolatry? – Part 2: what were ancient people thinking.” (12 February)

Dominic Bnonn Tennant. 2015. “Are the first and second commandments morally distinguishable?” (21 September)

Recent Comments