How Should Evangelicals Respond?

Right – Hank Hanegraaff being received into the Orthodox Church – Palm Sunday 2017

On 9 April 2017, Hank Hanegraaff – also known as the “Bible Answer Man” – was received into the Orthodox Church. His conversion to Orthodoxy surprised many Evangelicals. Some have reacted negatively. The blog site Pulpit & Pen posted “The Bible Answer Man, Hank Hanegraaff, Leaves the Christian Faith?” In the article, Jeff Maples wrote a very negative assessment:

The Orthodox Church is a false expression of Christianity, much like the Roman Catholic Church, that is highly driven by graven images and denies the biblical doctrine of salvation by grace alone through faith alone, and instead, trusts in meritorious works and a sacramental system for salvation. [Emphasis added.]

A “false expression of Christianity” – really??!! But where are the facts to support his judgment? My impression from reading Mr. Maples’ brief article is that he needs to write a longer article in which he presents the arguments and evidence for his harsh assessment of Orthodoxy. Otherwise, he is just ranting and voicing unthinking prejudice.

Another negative but more tempered assessment can be found on the Reformed blog Triablogue’s “Hank Hanegraaff’s Promotion of Eastern Orthodoxy.” Jason Engwer traces Mr. Hanegraaff’s gradual shift towards Orthodoxy through a detailed listing and notation of his podcasts comments. Mr. Engwer is not happy with Mr. Hanegraaff’s recent conversion because: (1) Mr. Hanegraaff is not adhering to the fine points of Evangelical beliefs; (2) Mr. Engwer questions Orthodoxy’s claim to historic roots; and (3) Mr. Engwer believes that Evangelicalism is healthier than Orthodoxy. Much of Jason Engwer’s beef against Orthodoxy is that it is not Protestant! However, it is curious that Mr. Engwer did not raise the question whether Orthodoxy is biblical. This ought to be the bottom-line question for any Evangelical.

Thoughtful Evangelicals should take the time to ask the following questions:

- Is Protestantism the only valid expression of Christianity?

- Does my salvation depend on my being Protestant?

- What are the marks of genuine Christianity?

- How do I know that my criteria for “genuine Christianity” are fair?

I recommend that Evangelicals read books like Peter Gillquist’s Becoming Orthodox, Robert Letham’s Through Western Eyes, and James Payton’s Light From the Christian East. Fr. Gillquist writes from an Orthodox perspective, Letham and Payton from the perspective of sympathetic Protestants. It is important to get the facts rather than to rush to judgment based on a hostile Protestant critique. I ask all readers to learn about Orthodoxy from seasoned, recognized Orthodox writers, not from hostile sources.

Many Evangelicals are probably wondering: “Why would someone who knows the Bible so well decide to become Orthodox? Is Hank Hanegraaff still a Christian?” The answer can be found in the words of Mr. Hanegraaff himself:

And I suppose over that period of time I have fallen ever more in love with my Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. It’s sort of like my wife—I have never been more in love with my wife than I am today, and I’ve never been more in love with my Lord Jesus Christ than I am today. I’ve been impacted by the whole idea of knowing Jesus Christ, experiencing Jesus Christ, and partaking of the graces of Jesus Christ through the Eucharist or the Lord’s Table. And that has become so central in my life, but as far as the statement that you mentioned, that I’ve left the Christian faith—nothing could be farther from the truth. In fact I believe what I have always believed, as codified in the Nicene Creed, and as championed by mere Christianity.

After reciting the entire Nicene Creed, he concluded, “In other words, I am as deeply committed to championing mere Christianity and the essentials of the historic Christian faith, as I have ever been.” [Source; Emphasis added.]

It is clear that Hank Hanegraaff’s continues to love Christ and the Bible, and that he cares deeply about Christ’s Church. Many other Protestant and Evangelical converts to Orthodoxy have found this to be the case as well. What we have found in Orthodoxy is a historically-grounded framework for understanding the Bible (i.e., Holy Tradition) and a reverent approach to worship (i.e., the Divine Liturgy). In these times of upheaval and shifting doctrines, we have found safe haven in the Orthodox Church.

Is Orthodoxy Biblical?

Another related question a thoughtful Evangelical might ask would be: “Does conversion to Orthodoxy entail a weakened commitment to the authority and inspiration of Scripture?” My answer to the question is that Orthodoxy is indeed biblical. It may come as a surprise to some that what they think of as unbiblical, e.g., icons, Holy Tradition, and honoring Mary are indeed profoundly biblical. I certainly was surprised when I became open to other ways of reading the Bible. I have written a number of articles that have dealt with these topics.

I became Orthodox, not in spite of the Bible, but because of the Bible! Orthodoxy is biblical Christianity without the Protestant add-ons.

Is Protestantism Biblical?

It may come as a shock to Evangelicals to discover that some of their core doctrines are based on a misreading of the Bible. Evangelicals read the Bible diligently, but they read it with a particular slant. It is this slant that causes them to misread the Bible.

For example, nowhere does the Bible teach “the Bible alone.” There are numerous passages about the authority, inspiration, and truthfulness of Scripture, but there is nothing about the Bible as the sole source for faith and practice. What the early Reformers did was to impose this axiom onto the Bible all the while ignoring passages that affirmed Holy Tradition. Once the question popped in my head: “Where does the Bible say ‘the Bible alone’?” I was able to read Bible with an open mind and with surprising results. It was like becoming aware that I was wearing glasses all the time and that the lenses were bending the light in a particular way.

Jason Engwer in the Reformed blog site Triablogue faults Hank Hanegraaff for affirming Scripture as “my rule of faith and practice” but not using the qualifier “alone.” Could it be because the phrase “bible alone” is not found in the Bible? It is a Protestant add-on. Hank Hanegraaff has by no means watered down his commitment to Scripture and is in fact living up to his title “Bible Answer Man”!

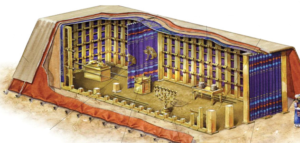

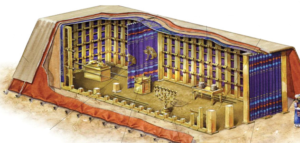

Tabernacle in Exodus

Many Evangelicals are so used to coming to church on Sunday mornings and seeing four blank walls. But if they were to read Exodus 26:31, 1 Kings 6:29-31, and 2 Chronicles 3:14 they would realize that the Moses’ Tabernacle and Solomon’s Temple were richly endowed with sacred images. That so many pastors skip over these biblical passages reflect Protestantism’s hidden tradition that promotes a certain way of viewing the Bible. The use of images in churches is an ancient practice that goes back to the catacombs and even has roots in Judaism. Nowhere in the Bible are we commanded to have four bare walls for our place of worship which raises the question which is more biblical: Orthodoxy with icons or Protestantism with bare walls?

In their reaction against Roman Catholicism, Protestant Reformers unwittingly threw the baby out with the bathwater. With the novel doctrine sola scriptura, Protestantism became unmoored from the Church Fathers. This resulted in Protestantism drifting from its roots in historic Christianity. With the novel doctrine sola fide — salvation by grace alone through faith alone – Protestantism created a new doctrinal standard by which they could judge themselves to be “true Christians” and any who differed from them to be unsaved and lost. The key defining element in early Christianity was Christology; the Protestant Reformers with sola fide created a new dogma with divisive consequences.

A thoughtful Evangelical must take into consideration the fact that none of the Church Fathers taught the Protestant dogma: salvation by grace alone through faith alone. While there were several theories in the early Church about how Christ saves us, there was no one dominant theory. Among the early motifs were: Christ the Great Physician, Christ the Second Adam, Christ the Conquering King Victorious over Death. The early Church taught that we are saved by grace through faith in Christ; but no one taught salvation as a private experience independent of the sacraments or life in the Church. A sober and honest Protestant must ask himself: “How could the Holy Spirit fail to teach ANY of the Church Fathers this supposedly essential doctrine?” Nonetheless, the entire Church was united in the belief that Christ saves us by his death on the Cross and his third day Resurrection. This understanding of the Gospel is especially evident in the Orthodox sacrament of baptism, its Sunday worship service (the Liturgy), and especially in the Easter (Pascha) service.

Don’t Be Afraid!

How should Evangelicals and Protestants respond to Hank Hanegraaff’s conversion to Orthodoxy? My answer is: With charity, curiosity, an open mind, and a willingness to learn about Orthodoxy. My hope is that they do not succumb to fearful paranoia or unthinking prejudice. Behind these negative reactions is fear. We need to bear in mind the words of the angels: Be not afraid!

Jeff Maples sees Hank Hanegraaff’s conversion as indicative of Evangelicalism’s “dismal state.” I agree with this assessment. Many who became Orthodox were very much aware of the unsettled drift, fragmentation, and prideful individualism that pervade Evangelicalism and Protestantism. However, another way to look at it is to see it as the culmination of Evangelicalism’s strengths. Among the recent Evangelical converts to Orthodoxy are pastors, seminarians, evangelists, missionaries, church elders, Sunday School teachers, and dedicated reliable lay people. They represent the best of Evangelicalism! Growing numbers of Evangelicals have become Orthodox, not because of a loss of faith in the Bible but rather from disenchantment with Protestantism’s hermeneutical chaos – one Bible but so many rival interpretations! They take the Bible and truth seriously. Many have been drawn by Orthodoxy’s reverent approach to worship. We don’t know the full story of Hank Hanegraaff’s journey to Orthodoxy, but it is sure to be an interesting one!

Come And See!

Christ is Risen! Truly He is Risen!

It is providential that Hank Hanegraaff joined the Orthodox Church this past Palm Sunday. This means that in a few days time, curious Protestants and Evangelicals will have the opportunity to visit Hank Hanegraaff’s new church on Easter Sunday. Orthodox churches can be found all over. Just use Google or Google Maps to find the nearest Orthodox parish. They have the chance to witness the highpoint of Orthodox worship, Easter (Pascha). Visitors should be aware that most Orthodox churches celebrate Easter on Saturday midnight. If they come on Easter Sunday, instead of a worship service they may find themselves witnessing an Easter egg hunt or a church picnic. But if you do attend the Pascha (Easter) service you will hear the joyous “Christ is Risen!” and the answering reply “He is Risen Indeed!”

Robert Arakaki

References

—-. “’Bible Answer Man’ Hank Hanegraaff Joins Orthodox Church.” In Pravoslavie. 10 April 2017.

Jeff Maples. “The Bible Answer Man, Hank Hanegraaff, Leaves the Christian Faith?” In Pulpit & Pen. 10 April 2017.

Jason Engwer. “Hank Hanegraaff’s Promotion of Eastern Orthodoxy.” In Triablogue. 8 April 2017.

Rod Dreher. “Bible Answer Man Embraces Orthodoxy.” 11 April 2017.

—-. “Hank Hanegraaff Converts to Orthodox Christianity.” In Finding the True Faith. 11 April 2017.

Recent Comments