Response to Pastor Steven Wedgeworth’s “What is Eastern Orthodoxy?” — Trinity Talk Interview No. 2 (16 November 2009)

Trinity Talk, an Internet radio blog, did a three part series with Pastor Steven Wedgeworth on the Eastern Orthodox Church. The interviews took place on November 2, 16, and 30, 2009. In this blog posting I will be responding to Pastor Wedgeworth’s November 16 presentation. This review will be structured along the lines of topics than chronology. Given the large number of topics covered, I have grouped them into four broad categories: (1) Orthodox worship, (2) the Orthodox Church, (3) Converts to Orthodoxy, and (4) West versus East. To facilitate the review I will be referencing his statements by minute and second in the pod cast.

I. Orthodox Worship: Icons • Congregational Participation • Visiting an Orthodox Church

Icons and Orthodox Worship

St. Nicholas Orthodox Church – Springdale, Arkansas

Wedgeworth describes what it’s like to enter an Orthodox church:

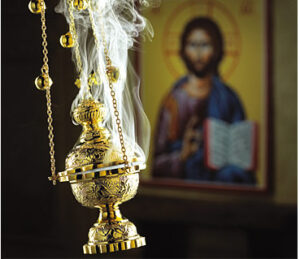

You walk into an Orthodox Church and to see an Orthodox sanctuary is an amazing thing. You see icons everywhere. All along the wall. You see large icons up in the front. You see icons of the Virgin Mary (they call her the Theotokos), of John the Baptist and of Jesus himself. (6:33)

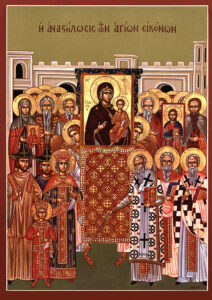

He does a good job presenting the Orthodox understanding of icons:

It’s a portal. It’s a connection between heaven and earth. (9:09)

Typically, the Orthodox answer is that you are not praying to the icon, but you are asking the saint pictured in the icon to pray for you. (8:30)

He notes that some Reformed Christians might get anxious at seeing Orthodox Christians venerating icons:

Your nerves will get tight when you see people bowing, burning incense, praying to the icon. Many Protestants will want to leave because of what they think is idolatry. (10:13)

The problem comes when you’re actually participating in the use of icons in worship. (10:45)

Pastor Wedgeworth did a good job of describing what one can expect to see upon entering an Orthodox church. He does not see any problem with Evangelicals attending a lecture or Sunday School class at an Orthodox Church (10:34). My advice to Evangelicals visiting an Orthodox worship service is: Don’t feel obligated to venerate the icons or to cross yourself. The best thing is to just observe what is going on in the services and don’t be quick to judge. Visiting an Orthodox service is a lot like visiting a foreign culture. Be respectful of your host culture and don’t be afraid to ask questions.

Let me offer an exhortation to first time visitors: Be slow to judge that which is unfamiliar to you. The ability to suspend judgment is critical to intellectual growth. Some people (Protestants included) are far too ready to make quick judgments before they understand both sides of the argument. Or, they believe they possess true understanding long before they have all the facts at hand. Remember, you cannot see or read peoples’ hearts or their motives.

Congregational Participation in Worship (7:51)

I wondered: Did Pastor Wedgeworth visit mostly Russian Orthodox churches? He notes:

The Orthodox church service is completely chanted or sung. (7:51) Other than that you’re not doing much. You’re not reading Scripture. You’re not engaged in lengthier prayers and responses.

It’s important to keep in mind that congregational participation vary across jurisdictions. I often visit a nearby Russian Orthodox church. Much of the services there are sung or chanted. Congregational participation is also affected by the amount of non-English used. The Greek Orthodox church I attend use a mixture of English and Greek. My experience has been that the Antiochian Orthodox and OCA churches are most likely to have all English services and encourage congregational participation.

Remember that style of participation varies even among Protestants: you have sober Reformed services, elaborate Anglican liturgy, exuberant charismatic services, and the simple Plymouth Brethren services. Just because the Orthodox do not participate “just-like” Protestants, does not mean they are not engaged, body and soul, in worship, there is more going on than you might think.

Evangelicals Visiting an Orthodox Church

Wedgeworth has a somewhat open attitude to Evangelicals visiting Orthodox services. It’s okay to attend Orthodox services, so long as you don’t venerate icons. As far as Wedgeworth’s criticism of Orthodox veneration of icons as idolatry, I would encourage visitors to go to an Orthodox Liturgy with an open mind. Go and observe what goes on in the Liturgy. Feel free to ask questions about what is going on in the Liturgy and the role of icons in Orthodox worship. And before criticizing the Orthodox approach to icons learn from both sides: the Reformed and the Orthodox. Don’t get your information from one side only. I’ve written a number of articles that attempt to explain icons to Reformed Christians who have reservations about the use of icons in Christian worship. (Please visit my Archives section – Icons.)

II. The Orthodox Church: Historical Development • Church Authority • Church Unity

Orthodoxy’s “Dirty Secret” — Historical Development (12:07)

Pastor Wedgeworth was likely mistaken when he inserted the word “exactly” into the statement: “This is the Apostolic Faith exactly as if you heard it from the Apostles’ mouths. (12:42)” Those who are well versed in Orthodoxy, if they do make such claims, are simply saying that there exists a deep, organic or fundamental continuity between Orthodox praxis today and the ancient Apostolic church. By ignoring these nuances Wedgeworth is setting up a simplistic dichotomy between “no change” versus “all has changed.”

I found Wedgeworth’s unqualified endorsement of evolutionary development disturbing:

We say some things now of necessity we would not have said earlier in the church’s history. (13:01)

When I heard him saying: “If you’re saying the Nicene Creed, you’re engaging in doctrinal development,” I found myself wondering how far he would take this thinking. He goes on to say that the controversy over Christ’s divinity was the result of Athanasius and Arius following a theological trajectory set by Origen (13:44). Wedgeworth went on:

They (Athanasius and Arius) both represent different strands of that tradition and so they butted heads and through that infighting we got new language and new rules about what can and cannot be said.

He made similar observations about the Nestorian and the Monophysite controversies (13:37). I found myself thinking: “Where’s the Scriptural teaching about Christ’s divinity? And where are the primitive Christological confessions that formed part of the oral tradition?” His cavalier treatment of the Ecumenical Councils strikes me as a risky position for an Evangelical theologian to take. Belittling the Ecumenical Councils leads to the unmooring of Evangelical theology from the historic Christian faith. Would it not be better to assume the Apostles really did receive the Truth promised from the Holy Spirit and that they delivered it to their disciples as Holy Tradition? Isn’t this the logical understanding based on the promises of Christ found in Scripture?

Wedgeworth sounds at times like a secular historian with a shaky commitment to the eternal truths of the Gospel. Are we think that after all twelve Apostles died that the church ended up as warring theological factions and that the Holy Spirit was not there to guide the Church into all truth? Are we to infer that the doctrines of Christ’s divinity, his two natures, and the Trinity were all the result of one church faction prevailing over others? Furthermore, Wedgeworth seems to ignore the well respected late Yale historian, Jaroslav Pelikan, who wrote about the traditioning process that goes on in the midst of doctrinal development. Wedgeworth’s relativistic approach to historical theology reminds me of an aphorism I heard often in liberal Protestant circles: “Yesterday’s heresy, today’s orthodoxy.” As a former member of a liberal Protestant denomination chills run down my back whenever I hear this aphorism.

Let’s pause and ask: How much has our theology influenced our reading of the New Testament and church history? Most early churches started in the Jewish synagogues. We also find the original Apostles and St. Paul continued to worship at the Jerusalem Temple (Acts 3:1, 21:26). Wouldn’t it be natural for us to expect our Reformed friends who espouse a covenantalist approach to the praxis and polity of the early church with the assumption of a fundamental, organic continuity with the Apostolic Church? Where the Dispensationalists tend to wipe the slate clean between Covenants (called Dispensations) and see ‘Discontinuity’ in God starting something mostly new and different from before, Reformed Covenantalists see a fundamental ‘Continuity’ in the way God works between Covenants. They see in biblical history God maturing what He started before; that what blooms and flowers in the Christological Covenant was there in seed form in God’s covenant with Abraham. But when it comes to the early Church and the deposit of the Faith once and all received from the Apostles, we find to our surprise Reformed Christians reading church history like a Dispensationalist or a Roman Catholic – with all manner of discontinuities and innovations. Why is this? The Protestant disavowal of apostolic continuity and the assumption of a Discontinuity between the Apostolic Church and the church of today bears a striking resemblance to Dispensationalism’s Gap Theory: the Age of the Church falls into a gap between the Old Testament prophecies about the restoration of national Israel and the literal millennial reign of Christ.

When we consider that the early Christians held the Apostolic Fathers and the early Church Fathers in high regard similar to the Apostles of Christ, we have to wonder where lies the Discontinuity by Wedgeworth. The Apostles were viewed as the foundation stones of the Church and the Church Fathers were viewed as building on the foundations laid by the Apostles. There is no hint of a widespread apostasy in church history. In assuming such a Discontinuity Wedgeworth seems to understanding church history like a Dispensationalist. If we regard the Apostolic Tradition handed down from the Apostles much like Moses’ Law and the Prophets – then our Reformed friends are being shy in applying the “General Equity” of the Law, and not only that, are acting more like selective, cherry-picking Anabaptist Antinomians! They mine the Apostolic Fathers for gems and nuggets they might like to keep for their use. But there is little regard for the binding validity of the Holy Tradition received by the Apostle from the Holy Spirit – and delivered once and for all to the Church (Jude 3).

This leaves me with the impression that paradoxically Wedgeworth does church history from the standpoint of a secular church historian and/or a fundamentalist dispensationalist. I would argue that a more sound approach to church history and historical theology is to combine the Reformed Covenantalist reading of Scripture with the Orthodox understanding of a fundamental continuity between the original Apostles and the church of the Seven Ecumenical Councils.

Church Authority (20:00)

Pastor Wedgeworth is technically correct when he states that apostolic succession is the basis for church authority (20:00). However as I noted in my earlier blog posting, he neglects the role of Holy Tradition. Authority in the Orthodox Church is not just institutional authority but is also grounded in Apostolic Tradition. If a bishop were to deviate from Tradition, his institutional authority is nullified. Furthermore, the authority of the bishop is catholic in nature. He exercises pastoral authority as part of the church catholic. There is no such thing as an independent bishop. Any bishop who attempts to lead his diocese independently of the church catholic becomes a schismatic and the parishes under his leadership cease to be churches. For this reason adherence to the Ecumenical Councils is an important indication of a valid church authority.

Wedgeworth presented accurately the Orthodox view of Protestantism: “We’re not the church. We’re a schism from a schism.” (22:22) This harsh assessment stems from the Orthodox understanding of the church described above. For Orthodoxy the Church is not a human creation, an association of like minded believers who love Jesus. For Orthodoxy the Church is a supernatural creation founded by Jesus Christ. It is the household of God, the New Israel, the Pillar of Truth.

Wedgeworth asserts that apostolic succession in the Byzantine Empire became nationalized. His insinuation that apostolic authority in Orthodoxy rests on the power of the state is misleading and wrong. The authority of the church is a covenantal authority bestowed by the Suzerain, Jesus Christ, on his designated followers, the Apostles. The Liturgy, especially the weekly Eucharist, is an act of covenant renewal; however, covenant renewal can only take place where there is valid covenant authority. Picking up a Bible and preaching from it does not suffice. One needs to be part of an unbroken chain of apostolic traditioning.

With respect to Apostolic Tradition Pastor Wedgeworth notes: “We Reformed Christians, we’re followers of the Apostles. We teach the same doctrines. And our pastors, priests, bishops come from the same line (20:44).” The problem is that picking up the Bible does not make you part of Apostolic Tradition; just as picking up a copy of the US Constitution makes you an American citizen. Nor does getting a law degree makes you an heir of the tradition of the colonial fathers!

Orthodox Unity in America and Abroad (24:53)

Pastor Wedgeworth strongly denies that Orthodoxy speaks with one voice (24:53). He notes that historically there were different patriarchates that operated on the basis of autocephaly — one being a head unto themselves. He notes that Moscow does not have to submit to Constantinople and visa versa. He notes that historically it was the Byzantine emperor who would have been the head of the church. What he put his signature on would have been the unifying doctrine (25:23). He seems to assume that the unity of the early church was principally an external administrative unity and not an internal organic unity based on a shared Apostolic Faith.

But the fact remains that Orthodox across jurisdictions share in the Orthodox Tradition: the Seven Ecumenical Councils, the Divine Liturgy, and church leadership based on Holy Tradition. Regardless of jurisdictions, they are united in faith and worship. The key sign of this unity is the fact that a member of the Antiochian Orthodox church can receive Communion at a Greek Orthodox or Russian Orthodox church. Their priests often substitute for each other; they teach at each other’s seminaries. Wedgeworth’s criticisms seem to imply that he expects to see administrative and organizational unity along the lines of the Roman Catholic church.

This high degree of real doctrinal and practical unity is all but lost in the way Wedgeworth highlighted the administrative overlaps and redundancies. It is as if he would prefer they unify under a Pope who speaks with one voice! This sort of obfuscation all but bespeaks an intent to argue for disunity where real unity exists. One can only speculate why he wishes to paint such a view of Orthodoxy? Granted, most Orthodox Christians pray and long for even more unity in America, but to imply Orthodoxy speaks with a many-voiced disarray – is all but unconscionable.

III. Converts to Orthodoxy (28:24)

Wedgeworth relates that he saw an article about Orthodoxy growing as Protestants and Catholics convert to Orthodoxy. He expressed surprise and skepticism at the claim that 70 percent of the priests in the Antiochian Orthodox Archdiocese are converts (28:44). He responds: “Let’s get real! That’s a real challenge to uniformity.” (29:39) I find his dismissive incredulity insulting. If he finds the fact that so many priests are converts so hard to believe all he has to do is do further research. He could contact a local Orthodox priest and ask: “Is it true that so many Orthodox priests are converts? And how has it affected Orthodox tradition having so many converts from non-Orthodox backgrounds?” It seems that he hasn’t taken the time to do the necessary follow-up. This I find disappointing. His Protestant listeners deserve better.

Here in Hawaii the statistics hold up. On the island of Oahu the priest of the Greek Orthodox church is a convert from the Episcopal Church. At the Russian Orthodox church the rector is a cradle Orthodox, while the assisting priest is a convert from Roman Catholicism. That comes out to 66 percent of the Orthodox clergy being converts. If we factor in the OCA mission on the Big Island, we find that the priest is a convert from the Episcopal Church. That changes the percentage from 66 percent to 75 percent. And if the paper work goes through for another priest from Canada who grew up unchurched the percentage goes up to 80 percent! So the empirical reality here in Hawaii matches the statistics cited elsewhere.

As far as converts attempting to bring in their own views and attempting to change things in the Orthodox church, Wedgeworth completely misunderstands the situation. In most instances converts from Protestantism and Roman Catholicism are traditionalists. They left churches where doctrinal or worship innovations were rampant and joined the Orthodox Church because of its doctrinal and liturgical stability.

IV. West versus East: Anti-Augustinianism • Original Sin • Neo-Palamism • Fr. Schmemann

Anti-Augustine Orthodoxy (15:41)

Pastor Wedgeworth describes the anti-Augustinian tendency among Orthodox Christians, especially immigrants from Russia or from the monasteries of Mount Athos. These Orthodox Christians want to be as far from the West as possible. Such that if something is from the West it must be bad, e.g., original sin, the doctrine of grace, predestination and free will. This strain of anti-Augustinianism is a post-1940s phenomenon and does not represent historic Orthodoxy.

My response is that in a forum like Trinity Talk, Pastor Wedgeworth should be discussing the mainstream views of Orthodoxy, not the more extreme versions. What he is doing is promoting unfounded caricatures that will hinder Orthodox-Reformed dialogue.

The Orthodox View of Original Sin (11:58)

It seems that Wedgeworth has encountered some Orthodox zealots who have branded the Western doctrine of original sin heretical (16:02). Wedgeworth notes that when pressed what they find objectionable about the Western doctrine of original sin they start to hedge and qualify their position. But to be fair it seems that these Orthodox Christians have been reading the Westminster Confession of Faith Chapter VI.3: “They being the root of all mankind, the guilt of this sin was imputed….”

Probably one of the biggest differences between Orthodox and Reformed Christians is not the question about the imputed nature of Original Sin, but the severity of the Fall. Following Augustine, the West came to understand the Fall as meaning that Adam fell from a position of mature perfection into a state of absolute depravity and bondage to sin. All of his descendants thereafter are now incapable of good desires, deeds, acts. In contrast the East following Irenaeus of Lyons came to understand the Fall as meaning that Adam starting position was as a youth fell from a state of undeveloped simplicity and that the image of God within us is distorted but not destroyed. Probably, the most consequential difference is that where the West understands human nature as totally lacking in free will, the Eastern tradition believes that even after the Fall humans still possess free will. This can be found in Kallistos Ware’s excellent introduction The Orthodox Church (pp. 222-225). For the Reformed the destruction of man’s free will is foundational for the doctrine of double predestination, and for the Orthodox the presence of free will even after the Fall is foundational to the Orthodox understanding of salvation as synergy — our cooperation with divine grace.

Fr. John S. Romanides article: “Original Sin According to St. Paul”

Fr. Ernesto Obregon aticle: “Roman Catholic and Orthodox differences on Original Sin”

Neo-Palamism as an Example of “New” Doctrine (14:35)

Pastor Wedgeworth’s claim that Neo-Palamism is a new and novel Orthodox doctrine shows his unfamiliarity with apophatic theology. This is a rich strand of spiritual writings that Pastor Wedgeworth seems to unaware of. When we compare Gregory’s theological method against his opponent Barlaam, who made use of the Western Scholasticism, we find him upholding a more ancient theological tradition.

Pastor Wedgeworth’s claim that Neo-Palamism is a new doctrine is flawed in more ways than one. His logic in citing modern Orthodox theologians like Vladimir Lossky, Georges Florovsky, John Meyendorff et al. as proof of neo-Palamism makes no sense. Just because a spate of books by Reformed theologians came out recently about Calvin’s belief in the mystical union doesn’t make it a new doctrine. Nor would it make it neo-Calvinism! For the Orthodox a doctrinal novelty is a teaching that breaks from the teachings of the church fathers.

Fr. Alexander Schmemann a Heretic? (29:44)

Schmemann’s writings has been popular among Protestants and has helped many in their conversion to Orthodoxy. I can still remember reading Schmemann’s For the Life of the World while waiting in line to confirm my plane reservation and being blown away by the sacramental world view Schmemann was presenting.

Pastor Wedgeworth concedes that many Protestants love the writings of the late Alexander Schmemann. This is a positive development and at the same time a curious thing in itself. There is little wonder why some Protestants from High-Church Reformed, Anglican and Lutheranism would enjoy Schmemann’s masterful elucidation of the Divine Liturgy in his For The Life of the World. But why Protestants pastors love and recommend it to each other without a thought of fallout is also puzzling. An elderly Greek Orthodox priest upon hearing that a Protestant pastor loved Schmemann’s book incredulously replied, “And he’s still Protestant?”

So I was dumbfounded to hear Pastor Wedgeworth claim that some bishops in Russia declared Fr. Schmemann to be heretic! I searched the Internet and found no corroborating evidence in support of what Wedgeworth said. I emailed several Orthodox priests and again came up empty. I invite Pastor Wedgeworth to give us additional supporting evidence or else retract his libelous statement about Fr. Schmemann.

[Also, a quick Google search shows Fr. Schmemann to be held in high regard by Alexander Solzhenitsyn. See Solzhenitsyn’s letter about Fr. Schmemann.]

Conclusion

As noted in the first blog review, it is evident that Pastor Wedgeworth has done a fair amount of reading about Orthodoxy and has even taken the trouble to attend Orthodox services. However, a similar pattern of weaknesses also recur: oversimplification, unbalanced presentation of the issues, unfamiliarity with Orthodoxy’s finer points, and some egregious errors that calls for correction or public retraction. I will hold off until my review of his third and final pod cast Trinity Talk interview for an overall assessment of how good a job he did in presenting Eastern Orthodoxy to his audience.

Robert Arakaki

Recent Comments