Charismatic Worship

by Hal Smith (Guest Contributor)

One of the main debates between the modern Charismatic movement and traditional Orthodox Christianity is over which better represents the Christianity of the Apostles’ era. Further, both Orthodox Christians and modern Rationalists see the modern charismatic movement as unreliable in its claims of miracles, because they see those claims as originating in the witnesses’ psychological phenomena, rather than as accurate depictions of material phenomena. Yet pure Rationalism would propose similar explanations for the miracles claimed in the early Church. How close, then, was the early Christian movement to the Charismatics of today, and how would Christians respond to the Rationalists’ claims about the early Church?

In this essay we will discuss four apparent key similarities between the Charismatic movement and the Early Church of the 1st to 2nd century that distinguish them from subsequent Orthodox Tradition: (1) expectations that the world would end within their generational cycle, i.e., within 120 years, (2) the practice of speaking in tongues, (3) spontaneous, improvised worship in their gatherings, and (4) much more frequent alleged gifts and miracles. These features represent major trends among Charismatics and the early Christians, however they are not necessary traits for their members. For example, despite the Apostles’ multilingualism at Pentecost, many early Christians lacked the “gift” of tongues, as Paul noted (1 Co 12:30).

The Orthodox Church’s teachings are those of the Ecumenical Councils, Scripture as understood by its Tradition, the Church Fathers, and its saints. Its beliefs include the plurality of views of modern theologians and laity, but they receive less weight than they would in Protestantism. Rationalism, on the other hand, is a modern philosophical movement that emphasizes skepticism and the scientific method, not just “rational” or logical thinking.1 According to the Encyclopedia Britannica this philosophy “regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge. In stressing the existence of a ‘natural light,’ rationalism has also been the rival of systems claiming esoteric knowledge, whether from mystical experience, revelation, or intuition.”2 So while the Orthodox Church recognizes and justifies the proclaimed gifts of the early Church, Rationalism attempts to debunk or propose non-miraculous explanations for them.

I. Expectations that the world would end within a generational cycle

One of the main features of the Charismatic movement is an expectation that Christ’s Second Coming and the world’s end would occur within the span of our current generation. Some early Christians had this expectation about their generation too. From a Rationalist perspective, this expectation could be disproven were it put into an explicit limited time frame that has passed. Consequently, when Orthodox commentators meet what could be failed, expired predictions for the world’s end, they avoid interpreting them as predictions whose chronologies can be measured beforehand in years or decades.

For example when Jesus asked rhetorically about John the Apostle “If I will that he tarry till I come, what is that to thee?,” an alleged saying by Jesus about John went “abroad among the brethren, that that disciple should not die: yet Jesus said not unto him, He shall not die; but,’ If I will that he tarry till I come, what is that to thee?’” (John 21:22-23). St. Paul appeared to imply that he would not have yet died by the time of Jesus’ Second Coming, when he wrote:

For this we say unto you by the word of the Lord, that we which are alive and remain unto the coming of the Lord shall not prevent them which are asleep. For the Lord himself shall descend from heaven with a shout, with the voice of the archangel, and with the trump of God: and the dead in Christ shall rise first: Then we which are alive and remain shall be caught up together with them in the clouds, to meet the Lord in the air: and so shall we ever be with the Lord (1 Th 4:15-17; KJV). [Note: biblical quotations are from the KJV unless noted otherwise.]

St. Theophan the Recluse

According to the 19th century Orthodox theologian St. Theophan the Recluse, some Church fathers considered Paul’s phrase “we who are alive” to be merely conditioned on Paul’s presence among the living at the time of Paul’s writing. St. Theophan, however, agreed with others’ view that Paul meant this unconditionally, on the basis that Christ said “Be alert, as you do not know the day or hour when the Son of Man will come” (Lk 12:40).3 St. Theophan concluded that “Thus everyone must expect it, be ready, keep oneself as if this minute he had reached his last day, holding in one’s heart the Lord’s future coming explains why in the New Testament the Last Day is portrayed as oncoming.

Alexander Lopukhin, another leading Orthodox theologian, commented that he was “inclined to the opinion that the Apostle hoped to be a living participant of the parousia. He would not have said ‘we the living’ if he was talking about a completely distant event. One must remember that the Apostle Paul kept the vividness of the expectation of the parousia until the end of his life, about which Php 4:5 and 1 Co 16:22 serves as a witness.”4 To those verses may be added Hebrews 1:2, in which Paul writes that God “hath in these last days spoken unto us by his Son.”

While spiritual readiness, if not expectation, of the End Times can be part of both biblical and Orthodox thinking, they do not share the practice of some Charismatics of proposing a date by which the Second Coming would occur. For example, the modern Adventist movement’s founder, William Miller, predicted this “Second Advent” for 1843, the non-occurrence of which caused the movement’s “Great Disappointment.” The Evangelical writer Hal Lindsey predicted the world’s likely end by 1989 in his famous book: The Late Great Planet Earth. Edgar Whisenant’s book: 88 Reasons Why the Rapture Will Be in 1988 sold 4.5 million copies, while the Trinity Broadcast Network televised preparations for the Rapture date.5

On the other hand, St. Theophan noted that Paul denied knowing a date for the world’s end and considered this a reason to doubt that Paul was absolutely certain that it would come in his lifetime. Paul explained that while Christians must not be caught unsurprised by the Second Coming, they would not foreknow its date either:

Now, brothers, about times and dates we do not need to write to you, for you know very well that the day of the Lord will come like a thief in the night. …But you, brothers, are not in darkness so that this day should surprise you like a thief (1 Th 5:1-4).

II. Glossolalia or “speaking in tongues”

Besides expectations about the End Times, another distinction of the Charismatic movement is the practice of “speaking in tongues.” Mark’s gospel ends with the resurrected Christ predicting that speaking in “new tongues” will be a sign that accompanies believers (Mk 16:17). This prophecy was apparently fulfilled at Pentecost, when the Apostles “were all filled with the Holy Ghost, and began to speak with other tongues, as the Spirit gave them utterance”(Acts 2:4). Bystanders, who came from many nations like Egypt, Parthia, and Mesopotamia, recognized their languages being spoken even though the Apostles were Galileans. Some bystanders mocked them as if they were full of “new wine,” but Peter denied it, saying that it was still 9 am, or by biblical calculation, “the third hour of the day” (Acts 2:15).

It’s important to note that in this incident, the Apostles were not babbling nonsense, but rather speaking other languages coherently. This gift of tongues was in accordance with their instructions from Jesus to evangelize the world (Mk 16:15-17). On the other hand, Acts presents the Pentecost event as spontaneous and energetic, as some bystanders portrayed it like drunkenness, and as it was accompanied with visions of tongues of flames on the Apostles. The Pentecost event is also portrayed as a miracle, since the Apostles were Galilean and presumably would have lacked natural exposure so many languages. Granted, it’s not inconceivable that they could have learned some creedal statements in other languages and been inspired to declare them collectively.

Accounts of miraculously speaking or being understood in a language unknown to the speaker exist in Orthodoxy, but they are very rare. One Orthodox monk relates:

St. Ephraim the Syrian visited St. Basil the Great (4th century) and the two communicated by this means: each spoke his own language and the other understood. In the actual life of Elder Porphyrios, it is recorded that an atheist French woman visited him in Greece and the two communicated in this way: Elder Porphyrios spoke Greek; the woman spoke French; and the two understood each other. The French woman was later received into the Orthodox Church. She is, as far as we know, still alive. This event would have occurred within the last 50 years.6

Although the Bible does not clearly record other instances of miraculous speaking in national tongues, it describes Christians in Corinth practicing incomprehensible speech or “glossolalia.” One possible instance is Paul’s reference to the language of angels in 1 Corinthians 13: “If I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, and have not charity, I am become as sounding brass.” This reference does not specify if the angelic “language” is incomprehensible glossolalia. But in the next chapter, Paul calls glossolalia “speaking in tongues” and a “spiritual gift” that he is thankful to have himself (1 Co 14:1, 18). He regards it as a “sign” predicted by the prophets:

In the law it is written, “With men of other tongues and other lips will I speak unto this people…” Wherefore tongues are for a sign, not to them that believe, but to them that believe not… (1 Co 14:21-22) [cf. Isaiah 28:11: “For with stammering lips and another tongue will [God] speak to this people.”]

Nonetheless, Paul considers glossolalia inferior to the gift of prophecy because the latter is comprehensible (1 Co 14:2-5):

For he that speaketh in an unknown tongue speaketh not unto men, but unto God: for no man understandeth him; howbeit in the spirit he speaketh mysteries… He that speaketh in an unknown tongue edifieth himself; but he that prophesieth edifieth the church. I would that ye all spake with tongues but rather that ye prophesied: for greater is he that prophesieth than he that speaketh with tongues, except he interpret, that the church may receive edifying….

The Orthodox theologian Lopukhin comments about Paul’s phrase “no man understandeth” the glossolalia:

This expression ‘no one’ is a very important proof against the proposition that the speech of the “speaker of tongues” was speech in a foreign language. If the Apostle understood such speech, he could not say that “no one” understands it, since in Corinth there were not a few newcomers from various countries of the world.7

St. John Chrysostom, however, may have thought that the Corinthians spoke foreign human languages like the Apostles in Acts 2, since he commented that the Corinthians “considered it a great gift… because the Apostles received it first of all and with such ceremony.”8

In any case, Paul instructs the Corinthians to always use an interpreter for their glossolalia and to allow at most three at a time to speak it, because “If… the whole church be come together into one place, and all speak with tongues, and there come in those that are unlearned, or unbelievers, will they not say that ye are mad?… God is not the author of confusion, but of peace” (1 Co 4:23,33).

In his essay “Speaking in Tongues: An Orthodox Perspective”, Fr. George Nicozisin accepted the glossolalia of the Corinthians as a real gift with which they praised God. He wrote that “The Greek Orthodox Church does not preclude the use of Glossolalia, but regards it was one of the minor gifts of the Holy Spirit… Better to ‘speak five words that can be understood … than speak thousands of words in strange tongues.’ (1 Cor. 14:19) This is the Orthodox Christian viewpoint.”9

An Orthodox monk remarked that:

In the Epistles of Paul it is recorded that a person might speak a new or even angelic language. However, the question arises, did a Church service that St Paul attended sound like an Assemblies of God service today? We really do not have any way to know… However, there is no recorded case that we are aware of that following voluntary Orthodox Baptism and Chrismation of an adult, that person spoke in tongues in the way people who have been ‘baptized in the Spirit’ do in the Assemblies of God or any other Pentecostalist or charismatic church or group. It just doesn’t happen in the Orthodox Church.

The Rationalist criticism of glossolalia is that it is fundamentally a psychological phenomenon. Fr. Seraphim Rose, a well-known Orthodox theologian, used Rationalist criticism to explain modern glossolalia in his book Charismatic Revival As a Sign of the Times:

Far from being given freely and spontaneously, without man’s interference–as are the true gifts of the Holy Spirit–speaking in tongues can be caused to occur quite predictably by a regular technique of concentrated group “prayer” accompanied by psychologically suggestive Protestant hymns (“He comes! He comes!”), culminating in a “laying on of hands,” and sometimes involving such purely physical efforts as repeating a given phrase over and over again (Koch p. 24), or just making sounds with the mouth. One person admits that, like many others, after speaking in tongues, “I often did mouth nonsense syllables in an effort to start the flow of prayer-in-tongues” (Sherrill p. 127); and such efforts, far from being discouraged, are actually advocated by Pentecostals. “Making sounds with the mouth is not ‘speaking-in-tongues,’ but it may signify an honest act of faith, which the Holy Spirit will honor by giving that person the power to speak in another language” (Harper p. 11)… A Jesuit “theologian” tells how he put such advice into practice: “After breakfast I felt almost physically drawn to the chapel where I sat down to pray. Following Jim’s description of his own reception of the gift of tongues, I began to say quietly to myself ‘la, la, la, la.’ To my immense consternation there ensued a rapid movement of tongue and lips accompanied by a tremendous feeling of inner devotion” (Gelpi p. 1).

Can any sober Orthodox Christian possibly confuse these dangerous psychic games with the gifts of the Holy Spirit?! This is the realm, rather, of psychic mechanisms which can be set in operation by means of definite psychological or physical techniques…it certainly bears no resemblance whatever to the spiritual gift described in the New Testament, and if anything is much closer to shamanistic “speaking in tongues” as practiced in primitive religions, where the shaman or witch doctor has a regular technique for going into a trance and then giving a message to or from a “god” in a tongue he has not learned.

Fr. Seraphim denied that the New Testament gift of tongues was basically an unusual self-induced psychological phenomenon. However, Acts 2 notes that bystanders who heard the Apostles at Pentecost concluded that the Apostles were drunk, and Paul in 1 Corinthians warned that witnesses of the Corinthians’ collective, simultaneous glossolalia could think them mad. Therefore, it appears that rationalists of that time might also have considered the Christians’ speaking in tongues to be a mentally confused practice. Further, if as Paul says “no man understandeth” the unknown tongues of glossolalia, then how could Paul’s instruction for someone to interpret it be reasonable?

The Orthodox response to this criticism can be that the Pentecost event and the early Christians’ speaking in tongues were not deliberate and artificial. Rather, at the Pentecost, the Apostles claimed to see flames and spoke comprehensible languages, which do not correspond to deliberately prompted garbling. Nor do we have a record of the Corinthians using mental techniques to intentionally prompt their glossolalia. As for the unexpected ability to interpret incomprehensible glossolalia, this too could be received as a spiritual gift, as Paul wrote: “Wherefore let him that speaketh in an unknown tongue pray that he may interpret” (1 Co 14:13).

III. Inclusion of free or informal styles of worship

In his first letter to the Corinthians, Paul suggested that their gatherings included an unprogrammed part for their members’ creativity, noting: “How is it then, brethren? when ye come together, every one of you hath a psalm, hath a doctrine, hath a tongue, hath a revelation, hath an interpretation. Let all things be done unto edifying” (1 Co 14:26). His own instructions allowed them to speak in tongues and give prophecies a few speakers at a time: “If any man speak in an unknown tongue, let it be by two, or at the most by three, and that by course; and let one interpret… Let the prophets speak two or three, and let the other judge” (1 Co 14:26, 29). The theologian Lopukhin commented: “The apostle lists further five kinds of inspired Christian art: a psalm or song, which the Christian composed, under the influence of special inspiration. This was an improvisation, as the very expression (‘has a Psalm’) used by the Apostle here shows.”11

Paul did demand that they give their individual prophecies in an orderly way, remarking that “the spirits of the prophets are subject to the prophets. For God is not the author of confusion, but of peace” (1 Co 14:32-33). He also demanded that although they might give their own songs and prophecies, they must be united in their faith and avoid factionalism (1 Co 1:10-13).

The Anglican theologian John Drane reflects an occasional Protestant perception that early Christian worship was informal, claiming:

At the very beginning the Christians met together every day, and their worship was spontaneous. This seems to have been regarded as the ideal, for… Paul describes… a Spirit-led participation in worship… (1 Corinthians 14:26-33). No doubt this was the natural way for things to happen at a time when the church generally met in someone’s house.

Drane wrote that as the Church grew, its worship developed a more structured form because:

At a time when there were significant debates about the nature of Christian faith there was the constant danger that those who were out of harmony with the church’s accepted beliefs and outlook would use this freedom to undermine the faith of the community. Because of this it became necessary to ensure that those who led the church’s worship could be relied upon to be faithful to the gospel… By the end of the first century a fixed form of service was in existence for the celebration of the Eucharist, and other forms of Christian worship were also becoming less open and spontaneous than they had been. Not everyone welcomed this, and even the [1st century] Didache (itself a handbook of church order) asserts that the ministry of Spirit-inspired speakers should not be curtailed in the interests of a formal church order.12

Drane’s claim that informal worship was initially ideally open and unstructured is a doubtful simplification. The Corinthians’ inclusion of individuals’ improvisation in the gatherings does not exclude that other parts of their worship was structured. That the Didache, with its instructions on worship structure, came from the late first century does not exclude the possibility of previous worship structures, detailed records of which have not survived. Early worship certainly included basic ritual elements like the Eucharist, scripture readings, sermons, and Psalms.

In his essay “From Evangelical to Orthodox,” Fr. Gregory Rogers related the experience of those like himself who shifted from an Evangelical perception of early Church worship to an Orthodox one:

I was partial to a loose, spontaneous, charismatic kind of approach toward worship, and expected to find that in the Scriptures and in history. To our surprise, our spontaneity itself began to lead us to order in worship, everything taking on a familiar pattern. Our study of the writings of Justin Martyr (about 150 A.D.) showed us that the Church has always had some kind of liturgical form to its worship. Even the New Testament showed evidences of this in the use of hymns and in the description of the meetings.13

Consequently, some Protestants like Charismatic Anglican Rev. Charles Alexander claim that early Christian worship included both set forms and moments for spontaneous worship: “Clearly, with Jewish backgrounds, the Apostles were used to some liturgical form of worship. Obviously, as we see in the Gentile context of Corinth (and in churches to middle of the second century), form plus informality became the norm.”14 So Alexander proposed arranging services with worship singing that may lead to “singing in the spirit, and then silence followed perhaps by “words of revelation” or “immediate ministry.”15

Eventually though, the Church did arrange its liturgies without space for individuals’ personal prophecies or doctrines. For example the Council of Laodicea in Phrygia (c. 365 AD) in its 59th canon banned privately composed psalms from being read in church. One of the Council’s motivations was likely to address the Phrygian-based Montanist movement, mentioned in Canon 8, who based its unorthodox teachings on private “revelations.” In any case, while improvised spontaneous prayers and prophesying were part of early Christian worship, their exact nature and role in early Christian gatherings is not clear.

IV. The belief that charismatic “gifts” are widespread

A fourth major trait of the Charismatic movement is its belief that gifts from the Holy Spirit like healing, speaking in tongues, visions, and prophesying are common, like they were in the Apostles’ time. At Pentecost, Peter described the sudden ability of the many Apostles gathered to speak in foreign tongues as an outpouring of God’s Spirit widely across genders, ages, and social castes (Acts 2:16-19):

[T]his is that which was spoken by the prophet Joel; “And it shall come to pass in the last days, saith God, I will pour out of my Spirit upon all flesh: and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy, and your young men shall see visions, and your old men shall dream dreams: And on my servants and on my handmaidens I will pour out in those days of my Spirit; and they shall prophesy”….

Furthermore, Charismatics point to Paul’s advice to the Corinthians to desire these gifts: “Pursue love, and zealously16 desire spiritual gifts, but especially that you may prophesy.… I wish you all spoke with tongues, but even more that you prophesied.” (1 Co 14:1, 5) Jerry Munk, former editor of the Orthodox newsletter Theosis and a rare Orthodox sympathizer of the Charismatic movement, wrote that the gifts spread beyond holy ascetics:

In the Old Testament we see many examples of the Holy Spirit coming upon people with little evidence of ascetic perfection: Samson, David, and Balaam’s ass come to mind. In the New Testament, the pattern continues: in Acts 11, the Spirit falls upon un-baptized Gentiles, while the book of I Corinthians is addressed to people who exercise the gifts of the Holy Spirit apart from the fruit of that same Spirit. After the New Testament period, we read in the Didache instructions for dealing with people exercising charismatic gifts while at the same time indulging the flesh. In none of these situations is it automatically assumed that the “spirit” behind the gift is from the devil. Just as one can receive Holy Communion unworthily, so one who is unworthy can exercise the gifts of the Spirit – but there is danger in doing so.17

Icon of St. Irenaeus of Lyons

St. Irenaeus, a 2nd century bishop, wrote as if the gifts were still frequent in his time:

“In like manner do we also hear many brethren in the church who possess prophetic gifts, and who through the Spirit speak all kinds of languages, and bring to light, for the general benefit, the hidden things of men and declare the mysteries of God.”18

He also wrote:

“Those who are in truth His disciples, receiving grace from Him, do in His name perform [miracles], so as to promote the welfare of other men, according to the gift which each one has received from Him. For some do certainly and truly drive out devils.”19

A common view in Orthodox tradition about the gifts is that they were frequent in the Apostles’ time, but then became severely restricted. Commenting on Paul’s reference to the “spiritual gifts” (1 Co 12:1-2), the famous 5th century theologian St. John Chrysostom noted their earlier frequency:

Well: what did happen then? Whoever was baptized he straightway spake with tongues and not with tongues only, but many also prophesied, and some also performed many other wonderful works… And one straightway spake in the Persian, another in the Roman, another in the Indian, another in some other such tongue: and this made manifest to them that were without [the Spirit] that it is the Spirit in the very person speaking.20

St. John Chrysostom

St. John Chrysostom remarked here:

This whole [phenomenon of gifts] is very obscure: but the obscurity is produced by our ignorance of the facts referred to and by their cessation, being such as then used to occur but now no longer take place. …Why look now, the cause too of the obscurity hath produced us again another question: namely, why did they then happen, and now do so no more?21

St. John Chrysostom answered this in his commentary on 1 Corinthians 2:5 (“That your faith should not stand in the wisdom of men, but in the power of God.”). He explained that the Apostles lacked a scholarly education and used wonders and insight from God to evangelize, rather than using human wisdom. Further, Christians of his time did not invent teachings, but rather relied on what they received from the Apostles, on the Divine Scriptures, and on the Apostles’ miracles. Secondly, “the more evident and overpowering” events had ceased because the greater such events are, the more they abridge the role of faith.22 If Jesus simply returned as God with His angels, then the event would drag its audience’s mind along and not be accounted for faith. Instead, Jesus told Thomas: “Blessed are they who have not seen, and yet have believed” (John 20:29). St. John Chrysostom also cited Paul’s words: “For now we walk by faith, not by sight” (2 Co 5:7).

Thirdly, he answered that miracles are continuing, but of a different kind, such as “the conversion of the world” and “the change from savage customs.” He asked rhetorically: “How did ‘the gates of hell’ not ‘prevail’ against “the Church?’ …Dost thou not see the whole world coming in; error extinguished; the austere wisdom… of the old monks shining brighter than the sun… the piety among Barbarians”?23 Fourthly, St. John Chrysostom commented “that our upright living seems” to be a “more trustworthy argument” than obvious miracles, because if the miracle-workers’ sins were prevalent, nobody would admire them or their miracles. However, “a pure life will have abundant power to stop the mouth of the devil himself.”24

Augustine of Hippo

St. Augustine also proposed that miracles had become far less frequent. In his Homily on John 6:10, he wrote:

In the earliest times “the Holy Spirit fell upon them that believed, and they spake with tongues”(paraphrasing Acts 2:4) which they had not learned, “as the Spirit gave them utterance.” These were signs adapted to the time. For it was fitting that there be this sign of the Holy Spirit in all tongues to show that the Gospel of God was to run through all tongues over the whole earth. That was done for a sign, and it passed away.25

While the Orthodox Church considers the gifts less widespread, according to Bishop Ignatius, they exist in Orthodox Christians “who have attained Christian perfection, purified and prepared beforehand by repentance.”26 They “are given to the Saints of God solely at God’s good will and God’s action, and not by the will of men and not by one’s own power. They are given unexpectedly, extremely rarely, in cases of extreme need, by God’s wondrous providence, and not just at random.”27 Fr. Seraphim Rose included among the “great miracle workers” in the Orthodox Church St. Seraphim of Sarov in the 19th century, and St. John Kronstadt, Elder Paisios, and Elder Porphyrios in the 20th. He noted that before all these miracle workers “either received the charisms or publicly exercised them they went through the preparation of a long and arduous asceticism so that they might be spiritually cleansed from their tendencies to sin. Such Elders and Saints are… characterized by their rareness.”28

Fr. Seraphim continued:

This is different from Pentecostalist circles where the charisms are acquired quickly (sometimes it seems that all it takes is to go to a revival). The charisms are also quite common (how many persons are claiming to be Apostles and Prophets today?)… These charisms are often exercised by persons who might not only lack distinction for their holiness but might even be involved in serious sin. There’s nothing odder than a great miracle worker who gets a divorce on account of his adultery.29

Illegal power lines

If the gifts are no longer widespread, how does Orthodoxy explain the miracles that modern Charismatics claim to perform? Fr. Paisius of St. Herman’s Monastery in California considered the possibility that some of them may be real phenomena, but not necessarily done “in the spirit of our ‘Meek and Lowly’ Lord Jesus Christ.”30 As such, they may cause harm by increasing the “miracle worker’s” pride. He noted that in Matthew 7:22-23, Jesus considered some who claimed to perform miracles in His name to be working lawlessness. Fr. Paisius gave as an analogy the practice of illegally using an electric cable to steal power from a power line.

Another Orthodox explanation for some of the Charismatics’ frequent miracles is that they could be illusory. St. Seraphim of Sarov warned against a sickness “called ‘prelest’ [in Russian], or spiritual delusion, imagining oneself to be near to God and to the realm of the divine and supernatural. Even zealous ascetics in monasteries are sometimes subject to this delusion, but of course, laymen who are zealous in external struggles called ‘podvigi’ [in Russian], undergo it much more frequently. Surpassing their acquaintances in struggles of prayer and fasting, they imagine that they are seers of divine visions, or at least of dreams inspired by grace. In every event of their lives, they see special intentional directions from God or their guardian angel. And then they start imagining that they are God’s elect, and often try to foretell the future. The Holy Fathers armed themselves against nothing else so fiercely as against this sickness — prelest.”31

The Rationalist response to the claims of widespread gifts in the early Church would be that such gifts were just as illusory as they are among Charismatics today. From the Rationalist viewpoint, with its skeptical view of miracles, such gifts would not have been even initially widespread in reality; thus they would not have undergone “Cessation” either. Rather, those “gifts” would have been delusions whose later appearances received less attention as the Church became institutionalized, and brought more educated people into its leadership.

While Drane proposed that the Church began to avoid spontaneous worship because dissidents could use it to undermine its teachings,32 one could also use Drane’s practical explanation to understand the Church’s reduced focus on individuals’ ongoing visions and prophecies more broadly. For example, in the late 2nd century the Church disputed with the Montanists, a Christian group that: gave special salaries to their own preachers,33 forbade women from wearing ornaments,34 claimed that their headquarters of Phrygia was the New Jerusalem, and justified their unorthodox claims by ecstatic states, visions, and spontaneous utterances. The debate with the Montanists was also one of the primary instances when the Church began to oppose an emphasis on ongoing independent prophecies for church decisions.

A Rationalist would propose that if genuine miraculous “gifts” after the first century became rare and the alleged ones were usually illusions, then this suggests that the same was true in the first century as well. While St. John Chrysostom claimed that Christianity’s ongoing spread far around the world was miraculous, a Rationalist could propose that it spread naturally because its beliefs and teachings were extremely appealing.

St. John Chrysostom responded to the claim that miracles were absent “even in the times of the Apostles” by noting the intense challenges the evangelists overcame:

If signs were not done at that time, how did they, chased, and persecuted, and trembling, and in chains, and having become the common enemies of the world, and exposed to all as a mark for ill usage, and with nothing of their own to allure, neither speech, nor show, nor wealth, nor city, nor nation, nor family, nor pursuit, nor glory, nor any such like thing; but with all things contrary, ignorance, meanness, poverty, hatred, enmity, and setting themselves against whole commonwealths, and with such a message to declare; how, I say, did they work conviction? For both the precepts brought much labor, and the doctrines many dangers. And they that heard and were to obey, had been brought up in luxury and drunkenness, and in great wickedness. Tell me then, how did they convince? …For… If without signs they wrought conviction, far greater does the wonder appear.35

V. Conclusion

In review, the 1st century Christians shared common elements with modern Charismatics at first glance, but there are important differences. Many early Christians lived in expectation that some of them would live to see Jesus’ Second Coming and the world’s end. Their worship included speaking in incomprehensible tongues and moments for free, independent creative prophesying. And they portrayed such gifts of the Spirit as widespread and frequent in their church gatherings.

Rationalists tend to see premature expectations of the Second Coming as failures, and glossolalia as a fundamentally psychological phenomenon. Rationalism is irrelevant as to whether Christians include time for individualistic creativity, like spontaneous praises, in their services. However, Rationalism would be skeptical of the early Christians’ claims of widespread miracles, since it is skeptical of miracles in general.

For its part, the Orthodox Church avoids interpreting New Testament writings as categorically predicting that the Second Coming would occur in the 1st-2nd centuries. For example, it interprets Paul’s reference to “we which are alive and remain unto the” Second Coming as conditional or as reflecting Christian strong, healthy preparedness for Jesus’ return. The Church often agrees with the Rationalists that glossolalia and other “gifts” are psychological when the claim is made about the modern Charismatic movement. Otherwise, the Church claims that Charismatics experience are real phenomena, but that their gifts are frequently flawed as not in accordance with God’s preferences, like meekness, deep morality, deep contemplation, etc. Orthodox Christians like Fr. Seraphim Rose distinguish speaking in tongues in the early Church from that of modern Charismatics by portraying the former as either intelligible foreign languages or a spontaneous gift, while portraying the latter as spouting gibberish intentionally learned through psychological mechanisms. However, the degree of similarity between the Corinthians’ and Charismatics’ glossolalia remains an open question.

Orthodoxy does not deny that some early Christian gatherings included special moments for performing gifts like glossolalia. But while the exact role of those moments in early Christian worship is not clear, the Orthodox Church emphasizes that early services involved the same basic ritual elements as traditional Christian worship, like prayers, psalms, songs, Scripture readings, homilies, and the Eucharist.

Finally, the Church considers gifts like healings, visions, and speaking in tongues to have been far more common in the era of the Apostles. However, Church Fathers like St. John Chrysostom attributed their reduction or “cessation” to Christianity’s greater spiritual value placed on faith to generate acceptance, rather than on overpowering evidence to compel belief. Once Jesus and the Apostles revealed and supported their teachings with widespread, impressive miracles, then it became less necessary to rely on further miracles to motivate faith.

Hal Smith

About the author. Hal Smith converted to Orthodoxy at age 17. He works as a Russian-English translator and attends an OCA parish in Eastern Pennsylvania. He administers Rakovskii – a website about Old Testament prophecies.

1 BBC – Religions – Atheism: Rationalism, http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/atheism/types/rationalism.shtml

2 “Rationalism,” Encyclopedia Britannica, http://www.britannica.com/topic/rationalism

3 St. Theophan the Recluse, quoted in “Tolkovanie Svyatogo Pisaniya,” http://bible.optina.ru/new:1sol:04:15

4 Alexander P. Lopukin, Id.

5 Mark Jeffries, The Last Daze: The Truth About End-Times Theology, Lulu.com, p. 4.

6 Orthodox Monk, “The Gift of Tongues,” October 7, 2010, http://orthodoxmonk.blogspot.com/2010_10_01_archive.html

7 Alexander Lopukhin, “Interpretation Bible: Interpretation of the first epistle of the apostle Paul to the Corinthians,” http://azbyka.ru/otechnik/Lopuhin/tolkovaja_biblija_64/14

8 Commentaries on 1 Corinthians 14:1, http://bible.optina.ru/new:1kor:14:01

9 Fr. George Nicozisin, “Speaking in Tongues: An Orthodox Perspective,” http://orkut.google.com/c111009-td0acc91d040b3ec0.html

10 Corduroy, Did Eastern Fathers Pray in the Spirit?, July 11, 2009, http://mistercorduroy.blogspot.com/2009/07/did-eastern-fathers-prayer-in-spirit.html

11 Id.

12 Orthodox Monk, supra Note 6.

13 Alexander Lopukhin, “Interpretation Bible: Interpretation of the first epistle of the apostle Paul to the Corinthians,” Supra note 7.

14 John Drane, Introducing the New Testament, Lion Books, 2010, pp. 431-432.

15 Fr. Gregory Rogers, From Evangelical to Orthodox, http://www.pravmir.com/article_400.html

16 Charles Alexander, The Church I Couldn’t Find, WestBow Press, 2013, p. 112.

17 Id. at 130.

18 The Greek word used here is ζηλόω, pronounced zēloō.

19 Jerry Munk, “Reply to Fr. Seraphim Rose’s The Charismatic Revival,” December 4, 1997, http://www.workofchrist.com/Theosis/reply.htm

20 Irenaeus, “Against Heresies,” Book V, vi.

21 Id. at Book II, xxxii, section 4.

22 John Chrysostom Homily XXIX , http://www.piney.com/FathChrysHomXXIX.html

23 Id.

24 St. John Chrysostom Homily VI on 1st Corinthians, http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/220106.htm

25 Id.

26 Id.

27 St. Augustine, Homily on John 6:10, quoted in: Hieromonk Seraphim Rose of Platina, Charismatic Revival As a Sign of the Times, http://orthodoxinfo.com/inquirers/frseraphim_charismatics.aspx

28 Bishop Ignatius, quoted in Fr. Seraphim, The New “Outpouring of the Holy Spirit,” http://www.orthodoxphotos.com/readings/sign/outpouring.shtml

29 St. Isaac the Syrian, quoted in Fr. Seraphim, The New “Outpouring of the Holy Spirit,” supra note 28.

30 Fr. Seraphim, The New “Outpouring of the Holy Spirit,” supra note 28.

31 Id.

32 Correspondence with Fr. Paisius of St. Herman’s monastery, October-November 2015.

33 St. Seraphim of Sarov, “Gleanings from Orthodox Christian Authors and the Holy Fathers,” http://www.orthodox.net/gleanings/prelest.html

34 Drane, Supra note 14.

35 Eusebius of Caesarea, Ecclesiastical History, 5, 18

36 “Montanism.” Collier’s New Encyclopedia. 1921.

37 St. John Chrysostom Homily VI on 1st Corinthians, Supra note 24.

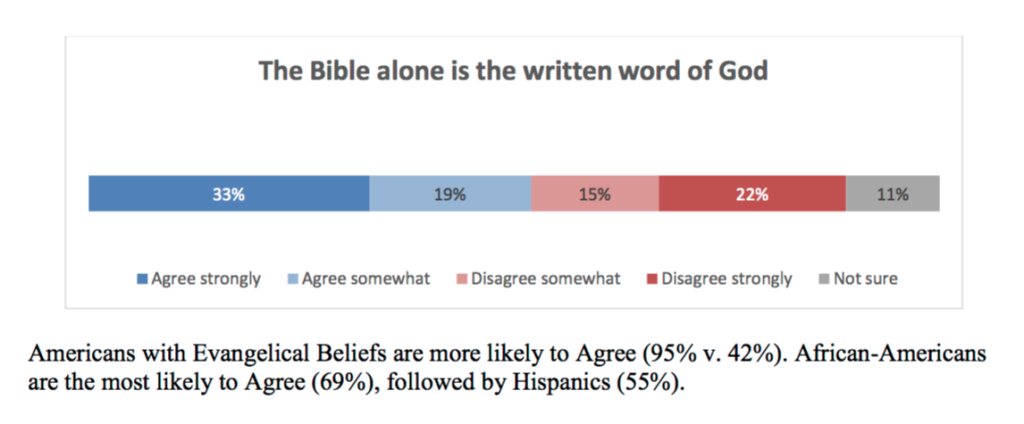

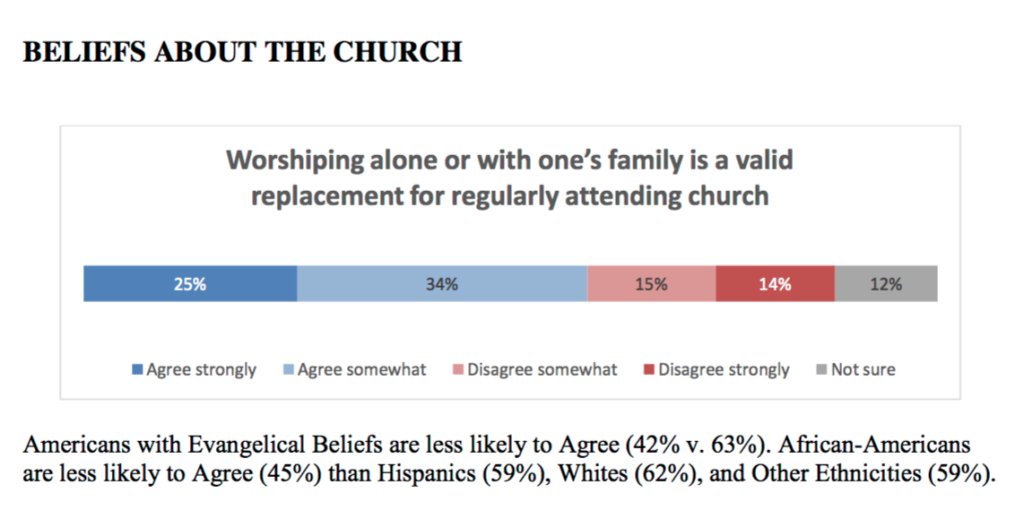

The results of the survey have generated considerable discussion among Protestants. In a recent article in First Things, Matthew Block bemoaned the spread of heretical beliefs among American Evangelicals. He notes that among “Evangelicals” – those who hold to core Evangelical beliefs – 71 percent believed Jesus to be a created being and 56 percent believed the Holy Spirit to be an impersonal force.

The results of the survey have generated considerable discussion among Protestants. In a recent article in First Things, Matthew Block bemoaned the spread of heretical beliefs among American Evangelicals. He notes that among “Evangelicals” – those who hold to core Evangelical beliefs – 71 percent believed Jesus to be a created being and 56 percent believed the Holy Spirit to be an impersonal force.

Recent Comments