I recently received an inquiry from someone with a Reformed background. He brought to my attention that a certain Protestant pastor is said to have claimed that the early Church Fathers were “church babies.” I have not been able to verify whether or not this pastor actually made that remark but I felt that the question deserved a good answer. This reader has also been in conversation with friends who are interested in Mercersburg Theology. One of them brought up the “fallacy of infallibility” objection against Orthodoxy. That is, “locally an Orthodox or Catholic bishop would have authority over his denomination but since the Church has been immature for the last 2000 years (being resurrected again in the 16th century) she is in no way infallible.” What follows is an attempt to answer that particular conversation but also in a way others can benefit.

My Response

Holy Tradition as the Basis for a Bishop’s Authority

Apostolic succession is key to understanding the office of the bishop. And, key to understanding apostolic succession is the traditioning process, i.e., the receiving, preserving, and transmitting of Apostolic Tradition. The office of the bishop is more than an institutional rank; it is a sacred trust. The bishop has been entrusted with what the apostle Paul referred to as the “good deposit.” (2 Timothy 1:14) A bishop has authority so long as he is faithful to the Tradition that Christ entrusted to his apostles. A heretical bishop loses his authority once he abandons Holy Tradition. Orthodoxy’s approach to the episcopacy focuses on the inner content, i.e., fidelity to Holy Tradition. In the West the focus is more on the outer form of the episcopal office, i.e., ritual succession (a matter of proper genealogy). This explains why they consider the Roman papacy valid despite innovations like the Filioque clause, purgatory, Mary’s Immaculate Conception, etc. It also explains why Anglicans consider themselves to have valid bishops despite their bishops’ failure to uphold the teachings of the Seven Ecumenical Councils and worse yet abandon traditional Christian morality. What counts for them is the proper rite being carried out when consecrating their bishops.

Vertical and Horizontal Accountability

Holy Tradition provides both vertical and horizontal accountability. Vertical accountability refers to the present day bishop being able to trace his lineage back to the original apostles. Horizontal accountability refers to the present day bishop holding doctrines and celebrating a liturgy similar to other bishops around the world who can trace their lineage back to the apostles.

Martial Arts as Tradition

In the martial arts, each school is run by a sensei or sifu (master teacher) who can trace his style to past master teachers. The sensei is one who earned the right to bear the name of a particular style of martial arts, to open his own dojo (school), and have his own students. The sensei is also one who has inherited from his teacher the authority to bestow belts (ranks) on his students, the highest rank being the black belt. This means that a student can verify his sensei’s claims by visiting other dojos, watching the other students, and talking with their teachers. Anyone can set up their own school of martial arts and give out black belts but for all of this to be meaningful one must be part of a living tradition. The point of this analogy is that in Protestantism anyone can set up his own “church” and claim “apostolic succession” just by holding a Bible in his hand. In Orthodoxy a congregation cannot be considered a valid church unless it is a Eucharistic community under the authority of the bishop (Ignatius’ Letter to the Smyrneans chapter 8). The Eucharist is the constitutive act of the local Christian community and access to the Eucharist is a sign that one belongs to the one holy catholic and apostolic Church.

The Eucharist Makes the Church

The Eucharist as a constitutive act can best be understood from the standpoint of covenant theology. Every covenant required a sacrifice for its ratification and Christ’s one-time death on the Cross was foundational for the New Covenant. When Jesus the Lamb of God died on the Cross the Old Covenant sacrificial system came to a close, and the New Covenant was put into effect. The sacrificial system of Leviticus instituted by Moses was superseded by the Eucharist instituted by Jesus Christ in the upper room with the twelve disciples. The implications of the real presence of Christ’s body and blood in the Eucharist are enormous. It is best understood not so much as a reenactment or a repetition of Christ’s one-time death on the Cross but rather an extension of Christ’s death on the Cross across space and time via the Divine Liturgy. The weekly Eucharist can be understood as an act of covenant renewal in which the vassal (the Christian) renews his commitment to the suzerain (Christ). It can also be understood as a covenant meal in which the suzerain (Christ) and his vassals (the Christian believers) come together as a sign of peace and friendship between two former enemies and as a sign of their common life together. Like the ancient Near Eastern covenant treaties the Gospels recall and re-enact the suzerain’s great deeds on behalf of the vassals. The New Testament records the terms of the covenant by which the vassal (the Christian) remains in good standing with the suzerain (Christ). So long as the vassal remains in a covenant relationship via the covenant meal (the Eucharist) he enjoys the benefits promised in the covenant document (the Bible). Skipping the meal with the suzerain raises questions about one’s relationship with the suzerain. An example of this would be David’s avoiding a meal with King Saul (1 Samuel 20:5, 24-29).

The Eucharist as a constitutive act explains why exclusion from the Eucharist is so consequential for Christian identity and one’s salvation. The fact that Roman Catholics are not allowed to receive Communion at Orthodox churches is a sign of the break between the two traditions. And this is why it is such a big deal for an Orthodox mission to transition from Reader Services to the Divine Liturgy; this marks the congregation becoming a proper church when the bishop assigns a priest to the mission who will be celebrating the Liturgy on a regular basis.

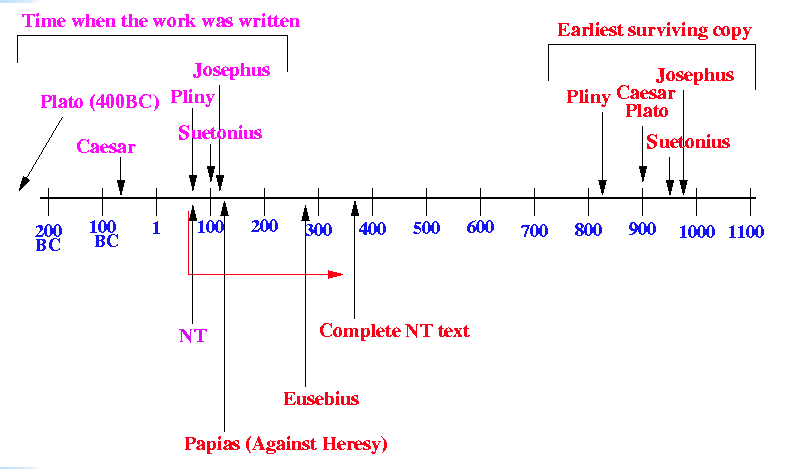

Evolutionary Paradigm of Church History Source

Paradigms of Church History

The concept of Holy Tradition has implications for how one understands church history. It implies the priority given to the preservation of Holy Tradition from generation to generation. That is why Orthodoxy looks askance at innovation. When I was a Protestant I was bewildered as to why Orthodoxy would want to hold on to a fossilized or ossified faith. However, I came to see the Christian Faith as something shared by the community, not as an expression of individual creative thought. Moreover, I came to appreciate that in the deepest sense Holy Tradition is living and dynamic in the way that a skillful conductor and a well-trained orchestra can infuse meaning and nuance into a music scored by Mozart or Bach. In the hands of a lackluster orchestra a musical classic can become lifeless and dull. What makes capital “T” Tradition a living tradition is the Church abiding in the Holy Spirit.

The Orthodox paradigm values doctrinal and liturgical stability. The opposite approach would be an evolutionary or progressive understanding of church history. This is the understanding that theology over time expands and improves upon what has come before, i.e., the present is superior to the past. I can sympathize with the progressive approach to church history. If one delights in thick tomes of systematic theologies and detailed doctrinal formulas, extensive commentaries like those produced by medieval Scholastics, the Reformers, and modern Protestants, plus modern-day seminaries with their erudite faculty members with Ph.D.s from world-renowned universities then the early Church Fathers would seem like small potatoes so to speak. But speaking as one who has studied at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary in Massachusetts and the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, California, I can attest that there is greater wisdom to be found in the early Church Fathers and in the classic liturgies of St. John Chrysostom and St. Basil the Great. For a humorous yet searing indictment of modern theology in comparison to the Church Fathers I recommend Thomas Oden’s After Modernity … What? The heart of the Christian Faith is not a detailed theological understanding of God but rather a trajectory that leads to union with Christ and life in the Trinity.

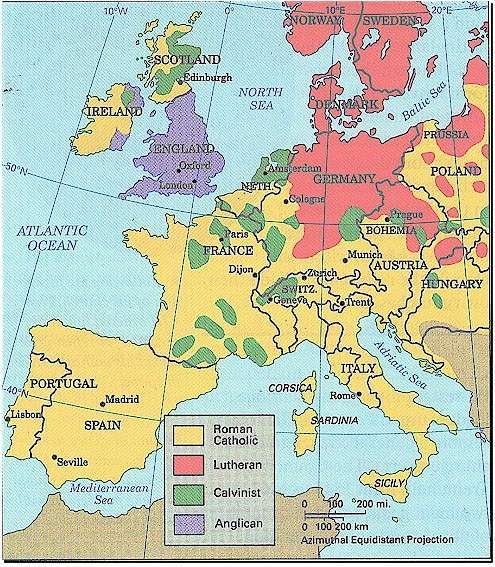

Honoring Our Fathers

There are other problems with the paradigm that denigrate the Church Fathers as “babies.” It is very disrespectful to look down one’s nose at the men who suffered martyrdom to preserve the Christian Faith against pagan Rome and who struggled to preserve the Gospel against the heretics. Furthermore, can one call their Christology and their doctrines of the Trinity immature? By what benchmark would your friend measure the early Church Fathers against modern day Protestants? By sola fide? By sola scriptura? This fixation on the progressive understanding of the Christian Faith is characteristic of Western Christianity. One sees it as the rationale for the elaborate theological systems of medieval Scholasticism. It serves as the justifying basis for Protestantism’s novel doctrines. Even more recently, it has been used to justify the new prophetic revelations in Pentecostal Christianity and the Liberal Christianity’s revisionist theologies and its new morality. The result has been the unceasing fracturing of Protestantism and an ever-intensifying theological chaos, leading to a religion unrecognizable to early Christians.

New Testament Teaching on Spiritual Maturity

We learn from Scripture that the apostles were acutely aware of the need for maturity in the Faith. The apostle Paul’s description in Ephesians 4:14 of “infants, tossed back and forth by the waves, and blown here and there by every wind of doctrine” describes well the predicament of modern day Protestants. In contrast to Protestantism’s stormy seas, Orthodoxy’s historic Faith resembles an unmoving rock that offers shelter and stability. The author of Hebrews expected spiritual maturity of his readers and rebuked those who “by now ought to be teachers, but have need someone teach them the elementary principles all over again.” (Hebrews 5:11) Paul’s exhortation to second generation Bishop Timothy to seek out “faithful men, who will be able to teach others also” shows the high value the early Church placed on maturity. (2 Timothy 2:2) There is not a hint whatsoever in Scripture that the apostles were inclined to entrust the Faith once for all delivered to the saints, to “spiritual babies.” Indeed the very opposite can be seen clear in the New Testament Scriptures along with the writings of the designated successors to the apostles (bishops) immediately afterwards.

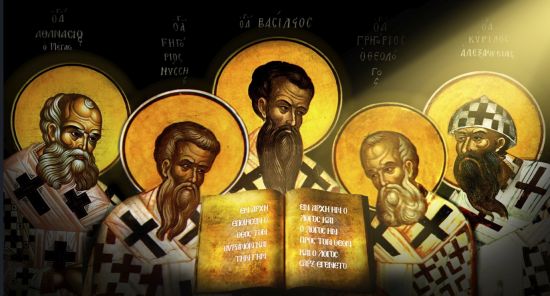

We should consider another often neglected historic fact. Much has been made of the timing of the Incarnation and the spread of the Gospel during the era of Pax Romana. The intellectual acumen of the early Fathers is a matter greatly neglected, especially by Protestants. This blind spot can be attributed in part to: (1) unfamiliarity with early Christianity, (2) the assumption that there is no significant difference between early Christianity and Roman Catholicism, and (3) the attitude of chronological snobbery, i.e., the thinking that Protestants are more advanced in their theologizing. But many if not most of the early bishops were brilliant intellectual giants fluent in several ancient languages and conversant in the best of Greek philosophy. Consider for example Irenaeus of Lyons, Athanasius the Great, Basil the Great, John Chrysostom, Gregory of Nyssa, and John of Damascus. They are far more likely to be intellectual giants and scholars of exceptional maturity — marked by a ascetic piety that should shame most modern Christians and theologians of our present today.

The Question of Infallibility

Your friend’s remark about the fallacy of infallibility begs the question as to where infallibility is to be found. Within Christianity there are three choices: infallibility resides in the Bible – the Protestant paradigm, infallibility resides in the Pope, the supreme bishop over all Christianity – the Roman Catholic paradigm, and infallibility resides in the Church, the Body of Christ – the Orthodox paradigm. For Orthodoxy infallibility is not intrinsic to the Church but rather a grace conferred by the Holy Spirit. Infallibility is an intrinsic property of the Spirit of Truth whom Christ sent to guide the Church (John 16:13). Orthodoxy believes that the Holy Spirit guided the Ecumenical Councils in their deliberations about the two natures of Christ and the Trinity. The proof of the pudding lies in the unity of the faith shared by the Orthodox throughout space and time; and in the doctrinal stability that Western Christians so often deride as static, ossified, fossilized, archaic, or more recently, “infantile.”

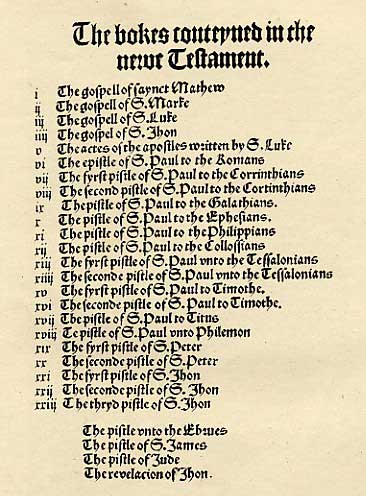

One of the greatest witnesses to Truth is the Divine Liturgy. This is because Scripture is primarily a liturgical document. The proper social context for Scripture is the Sunday Liturgy; private personal devotion in the home or the theologian’s study is secondary. That is why I invite inquirers to the Divine Liturgy and I ask them to consider that the Liturgy has been essentially unchanged for over a thousand years. This constancy in worship belies the widespread Protestant belief that the Church was in spiritual darkness until the Protestant Reformation of the 1500s. If your friend likes Mercersburg Theology then he would know that Nevin and Schaff rejected the “Blink On/Blink Off” (BOBO) paradigm of church history. This was the main point of Philip Schaff’s inaugural lecture which was later published in book form as The Principle of Protestantism. As a matter of fact it was those who held to the BOBO theory of church history that initiated a heresy trial against Schaff! What I appreciate about Mercersburg Theology is the attempt to show that Protestantism is not a novelty, but rooted in church history, and the attempt to show that Calvin’s understanding of the Real Presence in the Eucharist is rooted in the early Church Fathers. However, as I noted in my essay “An Eastern Orthodox Critique of Mercersburg Theology” – It can’t get you there. If your friend wants to hold to the BOBO theory, he must first show what benchmark he uses for determining doctrinal orthodoxy and give historical evidence of where and when the early Church went off the rails. If for example, he wants to use sola fide as a benchmark he has to first define the term then show that there were early Church Fathers who taught this doctrine. Furthermore, he must be able to give specific citations, not vague allusions or broad characterizations. And, I would note that the paradigm of early Church Fathers = spiritual babies and Protestant Reformers = spiritual adults is nothing more than a rephrasing of the BOBO theory.

Covenant Theology Leads to Holy Orthodoxy

Orthodoxy fits covenant theology much better than Protestantism. If the Bible is a covenant document, then the Eucharist is a covenant meal. At each Eucharist the covenant community renews its covenant commitment to the Suzerain (Christ). Thus, the infrequent celebration of the Lord’s Supper characteristic of Protestantism belies its covenant identity. Implicit to the covenant framework is the notion of covenant authority. Just as the Old Testament priests were authorized to offer sacrifices and teach the Torah (Malachi 2:7), so too the New Covenant has a priesthood. This is implied by the author of Hebrews claim: “We have an altar” (13:10) and Isaiah’s prophecy that God would take some of the Gentiles to be priests (66:20-21). Liturgical worship with an ordained priesthood was the standard format of Christian worship until the Protestant Reformation. The Reformed tradition’s disavowal of the episcopacy is rooted in its rejection of apostolic succession. This means that Protestantism has no historical link to the early Church. That link has been broken. The Protestant Reformation is much like the Northern Kingdom’s schismatic break from the Jerusalem Temple (1 Kings 12:25-33); the religious schism was more catastrophic than the political. Separation from the Levitical priesthood and the Temple in Jerusalem resulted in the eventual demise of the Northern Kingdom. Israel’s identity as a covenant community was grounded in fidelity to the Torah given by Moses at Mt. Sinai and in fidelity to the order of worship given in the latter half of the book of Exodus. One thing I admire about Protestant biblical scholarship is the great amount of effort given to textual criticism in the attempt to recover the original manuscripts. It is unfortunate that Protestantism has neglected the search for a priestly lineage that goes back to the apostles. Having the Bible is not enough for establishing a covenant identity. One needs a duly authorized priesthood, as well. Orthodoxy’s claim to a legitimate priesthood (the episcopacy) can be verified through an examination of its claim to apostolic succession.

In closing, holding a Bible in one’s hand does not make one a Christian any more than preaching from the Bible makes a gathering a church. This is because holding in one’s hands the covenant document (the Bible) does not make one a proper member of the covenant community. Participation in the covenant community requires covenant initiation (circumcision in the Old Covenant, baptism in the New Covenant) and participation in the covenant meal (Passover in the Old Covenant, the Eucharist in the New Covenant. Being part of the covenant community assumes that one is living under the authority of the covenant leadership. And just as important is fidelity to the terms of the covenant, i.e., living a life of love and justice to God and one another. I very much appreciate the Reformed tradition’s insight into the importance of the covenant, because it has helped me to identify the Orthodox Church as the true covenant community founded by the Suzerain Jesus Christ who came to restore us to the kingdom of God.

Robert Arakaki

Recommended Readings

Robert Arakaki. 2011. “The Biblical Basis for Holy Tradition.” OrthodoxBridge.com

Robert Arakaki. 2012. “An Eastern Orthodox Critique of Mercersburg Theology.” OrthodoxBridge.com

Robert Arakaki. 2014. “John Calvin and the ‘Fall of the Church.'” OthodoxBridge.com

Robert Arakaki. 2014. “Déjà Vu All Over Again.” OrthodoxBridge.com

Thomas Oden. 1990. After Modernity … What? Zondervan Publishing House.

Jaroslav Pelikan. 1976. The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600). The Christian Tradition. Vol. 1. University of Chicago Press.

Jaroslav Pelikan. 1986. The Vindication of Tradition. Yale University Press.

J.A. Thompson. 1964. The Ancient Near Eastern Treaties and the Old Testament. The Tyndale Press.

Ralph D. Winter. 2013. “The Kingdom Strikes Back: Ten Epochs of Redemptive History.” In Perspectives on the World Christian Movement. Ralph D. Winter and Steven C. Hawthorne, eds. William Carey Library Publishers.

Recent Comments