The Orthodox Church has made two major responses to the Protestant Reformation. The first response was to Lutheranism when the Lutheran theologians of Tübingen and Patriarch Jeremias II of Constantinople exchanged letters from 1573 to 1581. The exchange ended in an impasse due to irreconcilable theological differences. See the “Lutheran-Orthodox Dialogue in the Sixteenth Century.” The second response was to the Reformed tradition almost a century later in 1672 when a synod of bishops gathered in Jerusalem to respond to Cyril Lucaris’ Calvinistic 1629 Confession. The council resoundingly rejected Reformed theology and drafted a formal statement known as the Confession of Dositheus. It soon acquired the status of being Orthodoxy’s definitive stance on Reformed theology.

In this article, I will be examining the Confession of Dositheus to understand why Calvinism was rejected and the rationale for these rejections. The Jerusalem Synod made lengthy responses to three issues: (1) sola scriptura, (2) double predestination, and (3) icons and praying to the saints. In addition, it made shorter responses: (1) sola fide, (2) church government, (3) the sacraments, and (4) prayers for the dead. To assist the reader, certain parts of the quoted excerpts have been emphasized.

Cyril Lucaris

Cyril Lucaris (1572-1638) was born in Crete, which at the time was occupied by the Venetian Republic. His education was far ranging. He studied in Venice, Padua, Wittenberg, and Geneva, where he encountered the Reformed faith. For a brief period of time he was a professor at the Orthodox academy in Vilnus, Lithuania. He was ordained to the priesthood under the patriarchate of Alexandria. He later served as Patriarch of Alexandria from 1601 to 1620. Then from 1620 to his death in 1638, he served as Patriarch of Constantinople. Cyril’s tenure as Patriarch of Constantinople was a tumultuous one marked by his being deposed and reelected to the patriarchate several times. His unstable tenure reflects the intrigues of Turkish rule and Roman Catholicism’s efforts to extend its influence into Russia and the Ottoman Empire. In 1638, the Sultan ordered Cyril’s execution out of fear that he would stir up the Cossacks against him.

Cyril’s Confession

In 1629, Cyril’s Confession was published in Latin in Geneva. In the next several years, it would be translated into French, German, and English. Cyril’s Confession generated considerable controversy among the Orthodox. Between 1638 and 1691 six local councils condemned it (Ware p. 96). In 1638, a synod in Constantinople declared: “Anathema to Cyril, the wicked new iconoclast!” (Pelikan p. 285) Cyril’s embrace of Calvinism can be attributed to three factors: (1) the appeal of Reformed theology, (2) the lack of precision up till then on certain points of Orthodox theology (Pelikan p. 283), and (3) the advantage of currying the support of Protestants against Roman Catholicism.

Cyril’s Confession was controversial in other ways as well. There were some who believe that Cyril’s Confession was a forgery. It should be noted, however, that the Confession had been in circulation for about nine years prior to Cyril’s death in 1638. Furthermore, there is no evidence of Cyril having disavowed his Confession in writing. In his favor was the fact that Cyril was not deposed by a synod of bishops but by the Turkish Sultan.

A recent assessment of Cyril Lucaris can be found in Fr. Josiah Trenham’s Rock and Sand (2015). As a graduate of Westminster Seminary (Escondido, CA), Reformed Theological Seminary (Jackson, MS; Orlando, FL), and having received his doctorate under the supervision of Andrew Louth at University of Durham, England, Fr. Josiah is in a good position to assess the controversy about Cyril Lucaris’ theological leanings. He wrote:

Historians have differed on the authenticity of this confession, some affirming the authorship of Lucaris, and others noting that we have a large body of books and letters from the Patriarch in which he does not advocate Calvinist positions and is a defender of Holy Orthodoxy. There is no doubt that the Jesuits were seeking to undermine Lucaris and to brand him as a Calvinist and a betrayer to Holy Orthodoxy so that his valiant opposition to Latin intrigues would be weakened . . . . Though Patriarch Lucaris is said to have disavowed authorship of the Confession orally on several occasions, this was never done in writing.

There is some ambivalence as to Cyril’s posthumous status in Orthodoxy. The Patriarchate of Alexandria recognized him as a saint and martyr, but the other Orthodox jurisdictions have yet to accept this judgment of Cyril. I found several convoluted attempts to prove that Cyril was falsely accused of being a Protestant. In light of the absence of evidence that Cyril’s Confession was a forgery along with the absence of any evidence of Cyril disavowing the Confession, I lean towards Cyril’s 1629 Confession as a genuine evidence of Cyril’s having embraced the Reformed faith. I also find it noteworthy that two prominent scholars—Metropolitan Kallistos Ware and Yale professor Jaroslav Pelikan—assumed Cyril to be the author of the 1629 Confession. However, the main focus of this article will be the 1672 Synod’s response to Reformed theology rather than the status of Cyril Lucaris’ beliefs.

The Confession of Dositheus

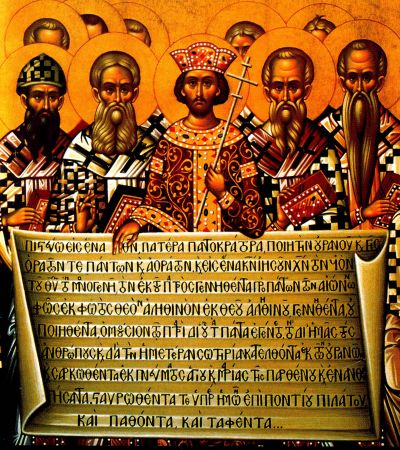

The Jerusalem Synod was convened in 1672 to respond to the controversy generated by Cyril’s Confession. It met 108 years after Calvin’s death and not long after the Reformed tradition had drawn up two major doctrinal statements: the Canons of Dort (1619) and the Westminster Confession (1646). In other words, the Synod was addressing Calvinism at a time when it had attained mature expression. The Jerusalem Synod issued the Confession of Dositheus which explicitly condemned the teachings of John Calvin. The document took its name from Dositheus Notaras, the Patriarch of Jerusalem who presided over the Synod.

The Confession of Dositheus consists of: an opening paragraph, eighteen decrees, four questions, and an epilogue. The Confession in no uncertain terms denounced John Calvin and the Reformed tradition.

. . . but would be the Church of the malignant {Psalm 25:5} as it is obvious the church of the heretics undoubtedly is, and especially that of Calvin, who are not ashamed to learn from the Church, and then to wickedly repudiate her. (Decree 2; Leith p. 487)

Here the Orthodox synod recognized Calvin’s acquaintance with the Church Fathers then it criticized him for abandoning the patristic consensus. Even more striking is the strong language used to describe the Reformed tradition as the “church of the heretics.” Also notable is the specificity of the document’s language. Cyril Lucaris is mentioned by name three times: in Decree 10 (Leith p. 492), Question 4 (Leith p. 515), and the Epilogue (Leith p. 516). Calvin is mentioned by name once in Decree 2 (Leith p. 487), and the Calvinists twice: in Decree 10 (Leith p. 492) and in Question 4 (Leith p. 513).

Sola Scriptura

Conservative Protestants and Evangelicals will be happy to find that in Decree 2, the Orthodox Church affirms the divine inspiration and infallibility of Scripture. However, they will find that the Synod repudiated the Protestant tenet of sola scriptura (the Bible alone), insisting that the Bible must be understood in light of how the Church interpreted the Bible.

We believe the Divine and Sacred Scriptures to be God-taught; and, therefore, we ought to believe the same without doubting; yet not otherwise than as the Catholic Church has interpreted and delivered the same. (Leith p. 486)

The Synod warned that without the Church’s teaching authority, the consequences will be men interpreting the Bible from their own standpoint, thereby opening the way for heresy, theological fragmentation, and denominationalism.

For if [we were to accept Scriptures] otherwise, each man holding every day a different sense concerning them, the Catholic Church [i.e., the Orthodox Church] would not by the grace of Christ continue to be the Church until this day, holding the same doctrine of faith, and always identically and steadfastly believing. But rather she would be torn into innumerable parties, and subject to heresies. (Leith p. 486)

As mentioned earlier, conservative Protestants and Evangelicals will be happy to learn that Orthodoxy affirms the infallibility of Scripture. However, they will need to wrestle with the claim that just as the Holy Spirit inspired the Bible, so likewise He inspired the Church. The concluding sentence of Decree 2 affirms that both the Bible and the Orthodox Church are infallible.

. . . it is impossible for her [the Church] to in any wise err, or to at all deceive, or be deceived; but like the Divine Scriptures, is infallible, and has perpetual authority.

Unlike Roman Catholicism which situates infallibility within the papacy, Orthodoxy understands infallibility to be the result of the Holy Spirit guiding the entire Orthodox Church into truth (see John 16:13). The magisterium (teaching authority) of the Orthodox Church is framed by Holy Tradition, e.g., the Nicene Creed, the Seven Ecumenical Councils, the Divine Liturgy, the Church Fathers, etc. Decree 12 explains in greater detail how the Holy Spirit through the Church Fathers keeps the Orthodox Church free from error. (Leith p. 496)

The Synod encouraged all Orthodox Christians to hear the Bible, a reference to the Scripture reading during the Liturgy. However in Question 1, it discouraged private reading of Scripture unless one had been properly trained in the interpretation and meaning of Scripture. (Leith pp. 506-507) Question 2 refutes the Protestant doctrine of the perspicuity of Scripture asserting that certain parts of Scripture are difficult to understand. (Leith p. 507) In Question 3, the canonicity of the Deuterocanonical books (aka Apocrypha)—which many Protestants do not recognize–is upheld. All these point to how Orthodoxy understands and approaches Scripture differently from Protestantism. (Leith pp. 507-508)

Double Predestination

Reformed theology is well known for its doctrine of double predestination. We find that the Orthodox Church holds a different understanding of predestination. The opening sentence of Decree 3 affirmed that God predestines people, but explicitly rejects the doctrine of double predestination.

We believe the most good God to have from eternity predestinated unto glory those whom He has chosen, and to have consigned unto condemnation those whom He has rejected; but not so that He would justify the one, and consign and condemn the other without cause. (Decree 3)

One might wonder how Orthodoxy can affirm God’s eternal decrees while rejecting double predestination. The answer is that unlike Calvinism which teaches unconditional election, Orthodoxy believes that humanity retained the capacity for free will after the Fall and that God in his omniscience foreknew how each person would exercise their free will.

But since He foreknew the one would make a right use of their free-will, and the other a wrong, He predestinated the one, or condemned the other. (Decree 3)

So [he still has] the same nature in which he was created, and the same power of his nature, that is free-will, living and operating, so that he is by nature able to choose and do what is good, and to avoid and hate what is evil. (Decree 14)

Decree 3’s statement that God would not justify or condemn “without cause”—a reference to the Calvinist doctrine of unconditional election—can be understood to teach conditional election, that is, dependent on the moral choices one makes.

It is highly instructive to note how the Jerusalem Synod understood human free will to be the basis for the doctrine of synergy (human cooperation with divine grace). Furthermore, synergy is at work in all people with two different outcomes: salvation or condemnation.

And we understand the use of free-will thus, that the Divine and illuminating grace, and which we call preventing [or, prevenient] grace, being, as a light to those in darkness, by the Divine goodness imparted to all, to those that are willing to obey this — for it is of use only to the willing, not to the unwilling — and co-operate with it, in what it requires as necessary to salvation, there is consequently granted particular grace. This grace co-operates with us, and enables us, and makes us to persevere in the love of God, that is to say, in performing those good things that God would have us to do, and which His preventing grace admonishes us that we should do, justifies us, and makes us predestinated. But those who will not obey, and co-operate with grace; and, therefore, will not observe those things that God would have us perform, and that abuse in the service of Satan the free-will, which they have received of God to perform voluntarily what is good, are consigned to eternal condemnation. (Decree 3)

The Orthodox understanding is that even after the Fall man retains free will and that God bestows prevenient grace on all peoples: “by the Divine goodness imparted to all.” Furthermore, it understands that prevenient grace “co-operates with us” pointing to the synergistic understanding of salvation in Christ. The application of the doctrine of synergy to the saved and the unsaved can be seen in the two parallel phrases “those that are willing to obey” and “those who will not obey, and co-operate with grace.” Thus, all humanity have received in some measure God’s grace, and have chosen either to respond positively to God’s grace or refuse it.

Decree 3’s affirmation of free will challenges one of the foundational premises of Reformed soteriology: monergism, the teaching that God is the sole source and determiner of our salvation. That is, if we are saved, it is because God so chose to save us, and if we are damned, it is because God in his inscrutable wisdom has chosen this fate for us. There is no room for free will or synergism in the monergistic paradigm of salvation found in Reformed theology.

Reading further into Decree 3, we find the tone of outrage and dismay by the fathers of the Jerusalem Synod at the heartless cruelty implicit in the Reformed doctrine of double predestination. In no uncertain terms, they condemned this teaching as impious and blasphemous.

But then to affirm that the Divine Will is thus solely and without cause the author of their condemnation, what greater defamation can be fixed upon God? and what greater injury and blasphemy can be offered to the Most High?

But of eternal punishment, of cruelty, of pitilessness, and of inhumanity, we never, never say God is the author, who tells us that there is joy in heaven over one sinner that repents.

Sola Fide

In Decree 13, the Confession of Dositheus rejects the core Protestant doctrine sola fide (justification by faith alone):

We believe a man to be not simply justified through faith alone, but through faith which works through love, that is to say, through faith and works. (Leith p. 496)

They explained that good works is a manifestation or fruit of faith, something quite different from the medieval Roman Catholic understanding of good works as meritorious.

But we regard works not as witnesses certifying our calling, but as being fruits in themselves, through which faith becomes efficacious, and as in themselves meriting, through the Divine promises {cf. 2 Corinthians 5:10} that each of the Faithful may receive what is done through his own body, whether it be good or bad.

The Jerusalem Synod’s brief response to sola fide here most likely reflects the Lutherans giving greater emphasis on sola fide than the Calvinists.

Icons and the Veneration of the Saints

In Question 4, the Jerusalem Synod made a lengthy rebuttal to Reformed iconoclasm. (Leith pp. 508-516). In response to the Calvinists citing the Second Commandment as grounds for the rejection of images, the Jerusalem Synod noted that the Second Commandment was later followed by God instructing Moses to make representations of the cherubim, oxen, and lions that were to be placed in the Temple. By placing the Second Commandment in the broader context, the Jerusalem synod did something Calvinists then and even today fail to do.

Therefore, when we contemplate God Himself saying at one time, “You shall not make for yourself any idol, or likeness; neither shall you adore them, nor serve them;” {Exodus 20:4,5; Deuteronomy 5:8,9} and at another, commanding that Cherubim should be made; {Exodus 25:18} and further, that oxen and lions {1 Kings 7:29} were placed in the Temple, we do not rashly consider the seriousness of these things. For faith is not in assurance; but, as has been said, considering the occasion and other circumstances we arrive at the right interpretation of the same; and we conclude that, “You shall not make for yourself any idol, or likeness,” is the same as saying, “You shall not adore strange Gods,” {Exodus 20:4} or rather, “You shall not commit idolatry.” (Leith p. 510)

The Synod concluded that the Second Commandment is best understood, not as condemning visual representations in places of worship, but rather the worship of false gods.

The Jerusalem Synod defended the veneration of icons by noting that it was an ancient practice going back to the time of the Apostles and that it has been affirmed by the Seventh Ecumenical Council (Nicea 787).

And as to the Saints whom they [the Calvinists] bring forward as saying that it is not lawful to adore Icons, we conclude that they [icons] rather help us since they in their sharp disputations inveighed both against those that adore the holy Icons with latria [Gk: adoration], as well as against those that bring the icons of their deceased relatives into the Church. They [the Calvinists] subjected to anathema those that so that, but not against the right adoration, either of the Saints, or of the holy Icons, or of the precious Cross, or of the other things that have been mentioned, especially since the holy Icons have been in the Church, and have been adored by the Faithful even from the times of the Apostles. This is recorded and proclaimed by very many with whom and after whom the Seventh Holy Ecumenical Synod puts to shame all heretical impudence. (Leith p. 510)

Related to the veneration of icons is the veneration of saints.

Since the Saints are and are acknowledged to be intercessors by the Catholic Church, as has been said in the Eighth Decree, it is time to say that we honor them as friends of God, and as praying for us to the God of all.

The Orthodox understanding of Christ’s resurrection strongly influenced its understanding that some kind of fellowship exists between the Church Militant on earth and the Church Triumphant in heaven, and that the saints are present before the throne of God. This contrasts sharply with the general practice of Calvinists and other Protestants of barely giving attention to the dead after their burial.

Other Differences

The Reformed tradition favored the presbyterian polity, a form of church government typified by the rule of assemblies of presbyters (elders). This is contrary to historic episcopacy in which the bishop’s authority rested in his being part of the chain of apostolic succession. For this reason the Jerusalem Synod felt obliged to defend the historic episcopacy (Decree 10).

Decrees 15 to 17 cover the sacraments in general, and baptism and the Eucharist in particular. The Jerusalem synod affirmed the necessity of infant baptism and rejected the notion of rebaptism. The real presence of Christ in the Eucharist is affirmed. What is interesting to note is that Luther’s doctrine of consubstantiation is rejected and the real presence defined in terms very much like the Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantation. This resemblance can be seen in the use of Aristotelian categories of substance and accidents. (Decree 17, Leith p. 503; see also Ware p. 97) The Confession stressed that the real presence is not something that can be explained. (Leith p. 504) It goes on to insist that the only valid Eucharist are those celebrated by an Orthodox priest authorized by a canonical Orthodox bishop. (Leith p. 505)

With respect to the afterlife, the Jerusalem Synod taught that upon death the soul departs either to joy or sorrow and that this is a temporary state until the resurrection, when the soul shall be reunited with the body (Decree 18; Leith p. 505). It also affirmed the efficacy of praying for the dead – a practice most Protestants avoid.

Summary and Conclusion

Whether or not Cyril Lucaris was in fact a Calvinist, the Confession of Dositheus makes it clear in no uncertain terms that it rejected Reformed theology. It repudiated the heart of Reformed soteriology through its rejection of double predestination, unconditional election, and by its affirmation of human free will after the Fall along with the synergistic understanding of salvation (Decree 3). Furthermore, it rejected other core Protestant doctrines: sola fide (Decree 13), sola scriptura (Decree 2). With respect to worship practices, Reformed iconoclasm is rejected (Question 4).

In light of its universal reception by Orthodoxy, the Confession of Dositheus can be considered the definitive dogmatic response by the Orthodox Church to Reformed theology. Metropolitan Kallistos Ware in The Orthodox Church noted:

While the doctrinal decisions of general councils are infallible, those of a local council or an individual bishop are always liable to error; but if such decisions are accepted by the rest of the Church, then they come to acquire Ecumenical authority (i.e. a universal authority similar to that possessed by the doctrinal statements of an Ecumenical Council). (pp. 202-203)

Thus, the Confession of Dositheus represents Orthodoxy’s official and definitive response to Calvinism. The Jerusalem Council’s rejection of so many of Protestantism’s core doctrines (sola fide and sola scriptura), as well as the Reformed tradition’s distinctive soteriology and ecclesiology, means that irreconcilable differences exist between the two traditions. So while the two traditions may share common ground with respect to the Trinity and Christology, they are far apart on so many other doctrines.

Cyril Lucaris’ pro-Reformed sympathies in the 1629 Confession had a positive influence on Orthodoxy. It forced the Orthodox Church to grapple with many of its implicitly held beliefs leading it to restate them with greater clarity and precision. Jaroslav Pelikan notes:

When Cyril Lucaris composed his Eastern Confession of the Christian Faith, he strove to adhere to official orthodoxy on the two basic dogmas and to use the official silence of the church on other questions as a warrant to graft Protestantism onto his Eastern Orthodoxy. The outcome of the controversy over his confession showed that the East in fact believed and taught much more than it confessed, but it was forced to make its teachings confessionally explicit in response to the challenge. (p. 283)

Thus, the Confession of Dositheus is immensely helpful for people who wish to compare and contrast Orthodoxy against Calvinism (the Reformed tradition). It is also very useful for Orthodox Christians who wish to defend their religion against their Reformed critics.

Robert Arakaki

Primary Sources

“Confession of Cyril Lucaris” (1629) at The Voice by Christian Research Institute. David Brachter, ed.

“The Confession of Dositheus (Eastern Orthodox, 1672)” at The Voice by Christian Research Institute. David Brachter, ed.

Lutheran-Orthodox Dialogue in the Sixteenth Century

Secondary Sources

Anthony J. Khokhar. “The ‘Calvinist Patriarch’ Cyril Lucaris and his Bible translations.”

John H. Leith, ed. Creeds of the Churches. “The Confession of Dositheus (1673),” pp. 485-517.

Jaroslav Pelikan. The Spirit of Eastern Christendom (600-1700). The Christian Tradition Volume 2.

Josiah Trenham. Rock and Sand.

Timothy (Kallistos) Ware. The Orthodox Church.

Recent Comments