IF NOT SOLA SCRIPTURA THEN WHAT?

IF NOT SOLA SCRIPTURA THEN WHAT?

The Biblical Basis for Holy Tradition

Note: This posting is based upon a paper I wrote in 2001. It was written to a broad audience: conservative Protestants and Evangelicals. All Scripture citations are from the NIV, unless noted otherwise.

Sola scriptura “the Bible alone” — one of the foundational tenets of Protestantism — is undergoing serious challenge in recent times as growing numbers of Evangelicals abandon this doctrine. Scott Hahn, a Presbyterian seminary professor, was dumbfounded when one of his students asked him, “Professor, where does the Bible teach that ‘Scripture alone’ is our sole authority?” (Hahn 1993:51). Unable to adequately answer his student’s question, Hahn went to some of Evangelicalism’s leading theologians who greeted his question with shock and disbelief that he would question one of the unspoken assumptions of Protestantism: that sola scriptura is biblical. This question precipitated a major theological crisis for Hahn that eventually led him to join the Roman Catholic Church.

This raises the question: if the Bible does not teach sola scriptura, then what does the Bible teach? In this posting I argue that the Bible teaches Holy Tradition, or the traditioning process, constitutes the basis for the Christian Faith. The Orthodox understanding of Holy Tradition is based upon three premises: (1) that Jesus entrusted to his apostles a body of teaching and practices, Holy Tradition; (2) that the apostles spread Holy Tradition through a variety of means: oral, written, and personal conduct, and (3) that the integrity of Holy Tradition is guaranteed by the Holy Spirit who guides the Church in unity and in truth.

The argument of this paper rests upon the assertion that the Bible teaches transmission, reception, and protection of a body of doctrines and practices originating in the life and ministry of Jesus Christ. The exegetical argument focuses on the recurrence of the words: παραλαμβανω (to receive) and παρεδωκα (to pass on). The Latin equivalent for παραδοσις is traditio from which we get tradition. Also, the Latin equivalents for παραλαμβανω are accipio and recipio from which the English words accept and receive are derived. Italics and bold emphases will be inserted in biblical quotations to support the arguments made in this paper.

Part I: The Biblical Evidence for Holy Tradition

Evangelism and the Traditioning Process

The traditioning process played a key role in the way Paul carried out his missionary mandate. In I Corinthians 15:1-3 Paul defines the Gospel within the framework of this process. In verse 1 he reminds the Corinthians that he had preached the gospel, that they had received it and had taken their stand on it. Then in verse 3 is a clear reference to the traditioning process when Paul says that what he had received, they had received:

Now brothers, I want to remind you of the gospel I preached to you, which you received and on which you have taken your stand. By this gospel you are saved, if you hold firmly to the word I preached to you. Otherwise, you have believed in vain.

For what I received I passed on to you as of first importance: that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures, and that he appeared to Peter, and then to the Twelve (I Corinthians 15:1-6).

In verse 3-4 Paul uses the same phrase “according to the Scriptures” two times. The word κατα “according” points to congruence and harmony between oral tradition and written tradition. Thus, for Paul there exists an organic interrelationship between written tradition (Scripture) and oral tradition (the gospel message). Paul did not put oral tradition over Scripture, neither did he put Scripture over oral tradition. Thus, what we see is neither the Protestantism’s placing Scripture over tradition nor Roman Catholicism’s placing Scripture under the Papacy but Orthodoxy’s approach of accepting Scripture in Tradition. Note: the phrase “according to the Scriptures” is used in the Nicene Creed.

The traditioning process likewise was foundational to Paul’s apostolic calling. In Galatians 1:8-9 the two phrases “we preached” and “you accepted” point to this process at work in Paul’s missionary strategy. He writes:

But even if we or an angel from heaven should preach a gospel other than the one we preached to you, let him be eternally condemned! As we have already said, so now I say again: If anybody is preaching to you a gospel other than what you accepted, let him be eternally condemned! (Galatians 1:8-9)

Paul’s apostolic authority derived from the fact that his gospel came directly from Jesus Christ and was “not something that man made up.” Paul does not base his anathemas on the principle of sola scriptura but on the basis of Tradition. Twice in verse 11 Paul asserts that he received his gospel directly from Christ:

I want you to know, brothers, that the gospel I preached to you is not something that man made up. I did not receive it from any man, nor was I taught it; rather, I received it by revelation from Jesus Christ (Galatians 1:11).

Paul’s thundering anathemas against anyone preaching an alternative gospel stems from his conviction that there can only be one gospel. The warning here is that any attempt to evangelize independent of the apostolic traditioning process is to risk preaching a false gospel or at best a partial gospel. While Paul’s extensive biblical exegesis in Galatians 3 and 4 affirms the authority and divine inspiration of the Old Testament, they cannot be taken to imply that Scripture is normative over all other sources of knowledge which is what sola scriptura calls for.

Holy Tradition can also be found in the preamble to Luke’s gospel. In his introduction to his gospel Luke describes the method by which he wrote his gospel:

Many have undertaken to draw up an account of the things that have been surely believed among us, just as they were handed down to us by those who from the first were eyewitnesses and servants of the word. Therefore, since I myself have carefully investigated everything from the beginning, it seemed good also to me to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus, so that you may know the certainty of the things you have been taught (Luke 1:1-4).

The phrase “handed down” points to the traditioning process as the foundational basis for Luke’s gospel. The process began with those who were eyewitnesses to Jesus’ life and ministry. What Luke did was to compile these accounts, sift through them, and commit them to writing. In the oral tradition there is a certain amount of fluidity in the content and format of the central message, with the transition to the written form the fluidity becomes fixed and acquires a permanence. There is no indication that Luke opposed the written form of the gospel against the earlier oral form.

The traditioning process can also be found at the end of Matthew’s gospel in the famous Great Commission passage:

Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you.

Many Evangelicals have memorized the Great Commission, but they overlook the integral part that the traditioning process plays in Christian missions. Christ’s command to the apostles that they teach the new believers all that he taught them can be understood as a reference to the traditioning process. Similar references can be found that link the traditioning process to Christian missions. In Matthew 10:40 Jesus said to his apostles: “He who receives you receives me….” and in Luke 10:16 is an emphasis on the oral component of the traditioning process: “He who listens to you listens to me….” There is no hint of the principle “bible alone” being foundational to Christian missions.

Tradition in the New Testament Church

The traditioning process was a part of the New Testament Church. This can be seen in Acts 2:42, a familiar passage to many Evangelicals:

They devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching and to the fellowship, to the breaking of bread and to the prayers.

The phrase “devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching” is a reference to the traditioning process. During those early days the new believers listened carefully to the apostles’ recalling the life and teaching of Christ. This verse contains other references to Holy Tradition: Eucharist indicated in “the breaking of bread”, formal liturgical prayers indicated by the definite article in “the prayers”; both of these components of Tradition can be found in the Orthodox Church but is largely absent among Evangelicals.

Many Evangelicals see the Bereans who “examined the Scriptures everyday to see if what Paul said was true” as an example of bible-based Christianity (Acts 17:11). What they overlook is the fact that the phrase “what Paul said” is a reference to oral tradition. In other words, everyday the Bereans were comparing Paul’s oral tradition against the Old Testament scriptures. Thus, one of Evangelicalism’s favorite proof-texts is actually a good illustration of the Orthodox approach to Scripture and Tradition!

In II Thessalonians 2:15 is found one of the clearest supports for Paul’s understanding that the apostolic witness could be valid under both written and oral forms. In no way does Paul indicate that the one was superior to the other:

So, then, brothers, stand firm and hold to the traditions we passed on to you, whether by word of mouth or by letter.

Orthodox Christians often appeal to this passage in the face of Protestantism’s sola scriptura. For Protestant Evangelicals the challenge is proving that the apostolic tradition is available exclusively in the written form. Another significant support for the Orthodox position can be found in I Thessalonians 2:13. In this passage Paul commends the Thessalonian Christians for their acceptance of the Christian message which came by word of mouth:

And we also thank God continually because, when you received the word of God, which you heard from us, you accepted it not as the word of men, but as it actually is, the word of God, which is at work in you who believe.

What is surprising about this passage is that Paul attributes to oral tradition the same standing as the word of God. Thus for Orthodox Christians the other components of Holy Tradition are just as inspired and authoritative as the Bible, the written word of God.

Another aspect of the traditioning process is imitation which Paul made frequent references to. In I Corinthians 11:1 Paul writes, “Follow my example, as I follow the example of Christ.” In Philippians 3:17 Paul writes, “Join with others in following my example, brothers, and take note of those who live according to the pattern we gave you.” In Philippians 4:9 Paul writes, “Whatever you have learned or received or heard from me, or seen in me — put it into practice. And the God of peace will be with you.” Using Philippians 4:9 we can liken the traditioning process is like a strong rope made up of five strands: (1) learning, (2) receiving, (3) hearing, (4) seeing, and (5) putting into practice. Imitation as a means of passing on Holy Tradition is consistent with the Incarnation — the Word made flesh, not the word written down on paper.

Worship in the early church was likewise based upon the traditioning process. In I Corinthians 11 Paul commends the Corinthians for being faithful to the traditions he gave them:

I praise you for remembering me in everything and for holding to the traditions, just as I passed them on to you (I Corinthians 11:2).

Paul makes a clear reference to the traditioning process when he talks about the Eucharistic celebration:

For I received from the Lord what I also passed on to you: The Lord Jesus, on the night he was betrayed, took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it and said, “This is my body, which is for you; do this in remembrance of me.” (I Corinthians 11:23-34)

Paul ends his section on the Eucharist with: “And when I come I will give further directions.” (I Corinthians 11:34) This tells us that what Paul gave the Corinthians was not a complete set of instructions on how to celebrate the Lord’s Supper, he would be coming later to give them further oral instructions. Thus, any Evangelical who seeks to base their theology of the sacraments upon I Corinthians 11 need to recognize that the written instructions that Paul gives in this section is incomplete.

Guarding the Apostolic Tradition

Protecting the Church against heresy and immorality is integral to the traditioning process. Without this vigilance, Tradition would undergo significant modification and cease to be the Tradition received from Christ. In Paul’s letters to Timothy we find a strong emphasis on the protection of the Gospel. By the time we get to Paul’s letters to Timothy we find Paul in the last days of his ministry. It is interesting to note that in light of his impending execution, Paul remained committed to the traditioning process with no indication that he had made the shift to the principle of sola scriptura. This is significant because it would be at this time, if any, that Paul would have given thought to committing his teachings to writing for posterity:

Timothy, guard what has been entrusted to your care (I Timothy 6:20).

What you heard from me, keep as the pattern of sound teaching, with faith and love in Christ Jesus. Guard the good deposit that was entrusted to you–guard it with the help of the Holy Spirit who lives in us (II Timothy 1:13-14).

A supporter of sola scriptura may point to the fact that in his letters to Timothy, Paul clearly holds to a high view of Scripture. In I Timothy 4:13 Paul admonishes Timothy to the public (liturgical) reading of the Scripture and in II Timothy 3:15-17 Paul affirms the divine inspiration of Scripture. However, it would be a non sequitir to argue that this means that Paul was teaching sola scriptura. This argument can only be made if it can be shown that Paul was teaching that the Scripture was authoritative over against other components of Tradition. However, Paul nowhere makes such a claim.

Another means of maintaining the integrity of the traditioning process was church discipline. Paul wrote to the Thessalonian Christians:

In the name of the Lord Jesus Christ, we command you, brothers, to keep away from every brother who is idle and does not live according to the tradition you received from us (II Thessalonians 3:6).

A similar approach can be seen in II John. The apostle John wrote his epistle at a time when the gnostic heresy was threatening to infiltrate the early Christian community. John instructed that only those who continued in the “teaching of Christ”, i.e., Tradition, were to be admitted into Christian fellowship. He writes:

Anyone who runs ahead and does not continue in the teaching of Christ does not have God; whoever continues in the teaching has both the Father and the Son. If anyone comes to you and does not bring this teaching, do not take him into your house or welcome him (II John 9-10).

Although a drastic action, excommunication was often necessary to preserve both the Christian community and Holy Tradition. The emphasis on “continuing in the teaching of Christ” lays the foundation for the historic practice of closed communion.

The Promise of the Holy Spirit

One fact that ought to puzzle Evangelicals is the fact that our Lord Jesus Christ never attempted to commit to writing his teachings. Even when Jesus knew of his impending death, he did not sit down to write up a summary of his teachings, neither did he instruct his disciples to write down his teachings for posterity. Instead, up to his last night on earth Jesus continued to use the oral method of teaching. In the Upper Room discourse Jesus did not promise an infallible all sufficient Bible, but the Holy Spirit who would guide the Church into all truth (John 16:12-15). Thus, it is the promise of the Holy Spirit that makes Holy Tradition work. The same Holy Spirit who inspired the apostles in their writing the New Testament documents also indwelt the Church, the Body of Christ.

Patristic theology forms one part of Tradition. The teachings of the Church Fathers are a fulfillment of Jesus’ promise that he would give the Holy Spirit who would guide us into all truth (John 14:23, 16:13). The teaching ministry of the Church Fathers is based upon the charismatic gifts that the Holy Spirit would bestow upon the Church, e.g., the gift of teaching and pastor- teachers (Ephesians 4:11, I Corinthians 12:28).

Another important part of Tradition are the Ecumenical Councils. In Acts 15 the Jerusalem Council was convened to met to deal with a theological crisis that threatened to split the Church and undermine the gospel. The Jerusalem Council announced its decision with, “It seemed good to us and the Holy Spirit…” (Acts 15:28). The Jerusalem Council set the precedent for future Ecumenical Councils that would be convened whenever the Church was confronted with heresy or other critical questions about the meaning of Scripture. The same Holy Spirit who inspired the apostles in their writing of the New Testament also guided the bishops at the Ecumenical Councils. Therefore, the Ecumenical Councils are not something added to the Bible but are the result of the same Holy Spirit who inspired the Holy Scriptures.

Part II. The Early Church and the Traditioning Process

Critical to the argument of this paper is the transitional period when the apostles were succeeded by the post-apostolic generation. Continuity between the apostles and the post-apostolic leadership can be seen as support for Holy Tradition. In II Timothy 2:2, Paul describes the process by which the Christian Faith was to be passed on to future generations:

And the things you have heard me say in the presence of many witnesses entrust to reliable men who will also be qualified to teach others.

What is notable about this verse is Paul’s emphasis on the careful selection and training of the post-apostolic generations of Christians who were to be entrusted with Holy Tradition. In this verse we find four links in the chain of tradition: (1) Paul, (2) Timothy, (3) “reliable men”, and (4) the “others.” What is striking about these passages is the aural component: what Timothy heard from Paul he was to pass on to others. Although many Evangelicals confine II Timothy 2:2 to the ordination ceremony of pastors, it makes more sense to understand the passage as referring to the passing on of apostolic tradition to future generations.

In Irenaeus we see how the early Church applied II Timothy 2:2. For Irenaeus the ability of a church to trace its roots back to the apostles was an important means to verifying its claim to correct doctrine and practice:

The tradition of the apostles, made clear in all the world, can be clearly seen in every church by those who wish to behold the truth. We can enumerate those who were established by the apostles as bishops in the churches, and their successors down to our time, none of whom taught or thought of anything like their (the heretics) mad ideas (Richardson 1970:371).

For Irenaeus “apostolic succession” was essential to the truth claims of the Christian faith. Apostolic succession is based, not just on formal ritual succession, but also in the holding to the same faith and practice as the Apostles. The Orthodox Church has faithfully adhered to both forms over the past twenty centuries. Each and every bishop and patriarch in the Orthodox Church can trace their link back to the Twelve Apostle. This is a claim that Protestants cannot make. (One such attempt known as Landmarkism make the outlandish claim that there existed an unbroken Baptist tradition from the time of Christ through the Dark Ages of the papacy until it reemerged during the Protestant Reformation. This popular movement generated enormous controversy among the pre-Civil War Baptist churches (see Ahlstrom’s A Religious History of the American People Vol. II pp. 178-181).)

After the apostles died, the traditioning process continued without interruption. Papias, bishop of Hierapolis (c. 60 – c. 130), lived during the crucial transitional period of the Apostles and their successors. The passage below shows Papias’ strong and active commitment to the traditioning process:

Unlike the great multitude, I did not take pleasure in those who talk much but those who teach the truth; not in those who stamp alien commandments on the memory but in those who keep the traditions given to the believers by the Lord and derived from truth itself. If by chance, though, someone came my way who had been a pupil and follower of the first elders, I inquired into the teachings of these elders: what Andrew or Peter said or what Philip or Thomas or James or John or Matthew or any other disciples of the Lord said…. (in Arnold 1970:168-169).

Papias approached Tradition primarily through person-to-person and oral contact. There is no evidence of the traditioning process becoming confined to the apostles’ writings.

Irenaeus of Lyons, regarded as the second century Church’s most important theologian, is a good example of the traditioning process. He was intimately acquainted with Polycarp, the spiritual son of the apostle John. Irenaeus’ letter To Florinus in Eusebius’ Church History (5.20) illustrates how the traditioning process was still going strong one century after the last of the apostles died:

…so that I can describe the place where blessed Polycarp sat and talked, his goings out and comings in, the character of his life, his personal appearance, his addresses to crowded congregations. I remember how he spoke of his intercourse with John and with others who had seen the Lord; how he repeated their words from memory; and how the things that he had heard them say about the Lord, His miracles and His teaching, things that he had heard direct from the eye-witnesses of the Word of Life, were proclaimed by Polycarp in complete harmony with Scripture (Eusebius 1965:227-228).

Irenaeus’ personal testimony shows how seriously and diligently the early Christian community committed itself to remembering the teachings of the apostles. Thus, the Church in the second century did not fall away as many Protestants assumed happened after the death of the apostles but continued to hold on to the teachings of the apostles. Another striking fact is how Irenaeus’ high view of Scripture complemented his commitment to oral tradition.

The Bible in the Early Church

Among the early Church Fathers there is clear evidence of their high regard for the Bible, but there is no evidence of the New Testament superseding the earlier oral traditions. Rather the emergence of the written New Testament was seen as a natural outcome of the overall traditioning process. In his Against the Heretics Irenaeus of Lyons describes the emergence of the four Gospels:

For we learned the plan of our salvation from no others than from those through whom the gospel came to us. They first preached it abroad, and then later by the will of God handed it down to us in Writings, to be the foundation and pillar of our faith …. They went out to the ends of the earth, preaching the good things that come to us from God, and proclaiming peace from heaven to men, all and each of them equally being in possession of the gospel of God. So Matthew among the Hebrews issued a Writing of the gospel in their own tongue, while Peter and Paul were preaching the gospel at Rome and founding the Church. After their decease Mark, the disciple and interpreter of Peter, also handed down to us in writing what Peter had preached. Then Luke, the follower of Paul, recorded in a book of the gospel as it was preached by him. Finally John, the disciple of the Lord, who had also lain on his breast, himself published the Gospel, while he was residing at Ephesus in Asia. All of them handed down to us that there is one God, maker of heaven and earth, proclaimed by the Law and the Prophets, and one Christ the Son of God (Richardson 1970:370).

A thoughtful Evangelical cannot but notice that the names of the authors that roll so easily off his/her tongue (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John) are not derived from Scripture but are extra-scriptural in source, i.e., they are part of the tradition of the early Church. While their names are mentioned in the New Testament, the New Testament does not name them as authors of particular books in the New Testament. Thus, for Irenaeus the New Testament did not stand apart from Tradition but was an integral part of Tradition. He saw the apostolic witness whether oral or written as valid.

For Irenaeus it conceivable to have a Christianity without the Bible, but not Christianity without Tradition:

Even if the apostles had not left their Writings to us, ought we not to follow the rule of the tradition which they handed down to those to whom they committed the churches? Many barbarian peoples who believe in Christ follow this rule, having [the message of their] salvation written in their hearts by the Spirit without paper and ink (Richardson 1970:374-375).

In a missionary situation where the bible has yet to be translated or the new believers belong to an oral culture, the newly planted church was expected to follow oral tradition.

One of the strongest arguments against sola scriptura can be found in Basil the Great (c. 329-379), a fourth century Church Father. In his On the Holy Spirit we find a clear discussion of the relationship between Scripture and Tradition:

Concerning the teachings of the Church, whether publicly proclaimed (kerygma) or reserved to members of the household of faith (dogmata), we have received some from written sources, while others have been given to us secretly, through apostolic tradition (1980:98).

For Basil the two sources are integrally related and cannot be separated without doing harm to one or the other. In the passage below Basil constructs a hypothetical scenario of what would happen if the Bible was separated from Holy Tradition:

Both sources have equal force in true religion. No one would deny either source–no one, at any rate, who is even slightly familiar with the ordinances of the Church. If we attacked the unwritten customs, claiming them to be of little importance, we would fatally mutilate the Gospel, not matter what our intentions–or rather, we would reduce the Gospel teachings to bare words (1980:98-99).

With uncanny prescience, Basil anticipates the seventeenth century English Puritans who sought to purge the church of non-biblical customs on the basis of sola scriptura. Many of the customs in the early Church such as making of the sign of the cross, the practice of facing eastwards when praying, the wording to be used for eucharistic prayers, the proper format for baptizing new converts, would be eliminated. Basil’s clear rejection of this principle shows conclusively that sola scriptura cannot be considered part of the historic Christian faith.

Thus, early church history does not support the Protestant understanding of Scripture standing separate from Tradition. The early Christians saw the emergence of a written New Testament as a natural step in the development of the Christian faith. The early church saw oral and written tradition as complementary and together forming a harmonious whole. Therefore, early church history refutes the Protestant claim of sola scriptura. It was only among the heterodox or heretics that we can find early precedents for sola scriptura (See D.H. Williams “The Search for Sola Scriptura in the Early Church”). None of the early Church Fathers ever held or taught sola scriptura. Basil the Great’s explicit rejection of sola scriptura together with the implicit understanding of other Church Fathers decisively prove that this principle was never part of the early Church and for that reason cannot be considered part of the historic Christian Faith.

Part III. The Protestant Rejection of Tradition

The Protestant rejection of Holy Tradition can be traced in large part to the Reformers’ struggle against medieval Catholicism in the 1500s. In their struggle to reform the Catholic Church the Reformers asserted the authority of sola scriptura against the tyranny of the Roman papacy. From the Orthodox perspective, many of the doctrines and practices rejected by Protestantism (purgatory, indulgences, the supremacy of the Pope, transubstantiation) are not part of Holy Tradition but innovations that emerged in post-Schism medieval Western Europe. Thus, it is important to keep in mind that when Protestants speak against “tradition,” they are thinking of something quite different from what Orthodox refer to as “Holy Tradition.” It is also important to keep in mind that the Protestant rejection of Tradition (with capital “T”) did not entail the exclusion of the historic creeds but the historic paradigm that embedded Scripture within the context of Tradition. What the Reformers did was to treat Scripture as autonomous from Tradition and regard as acceptable tradition (with small “t”) that which could be derived from Scripture.

Evangelicals’ aversion to tradition is also rooted in their being children of modernity. Modernity encourages the attitude that the old and traditional are inferior to the new and modern and that the new will supersede the old. This leads to Evangelicals distrusting the past or viewing the past as irrelevant or having no practical relevance. Much of this attitude can be traced to the American Revolution, the American frontier in the early 1800s, and the Civil War (see Mark Noll’s The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind, pp. 59 ff.).

The Traditions of Men

Evangelicals often point to Jesus’ confrontation with the Pharisees in Matthew 15:1-20 (see also Mark 7:17) as providing a biblical basis for their opposition to tradition. It is important that we note that Jesus did not issue a whole scale condemnation of tradition but the tradition of the Pharisees. The “tradition of the elders” is a reference to elaborate system of rules constructed by the rabbis during the Babylonian exile. This system of rules and regulations existed primarily in oral form until it was put down into writing around AD 200 in what is now called the Mishnah.

It should also be noted that the New Testament writers seemed to have no hesitation drawing on the oral tradition that paralleled the Old Testament scriptures: (1) the prophecy “He shall be called a Nazarene” (Matthew 2:23), (2) the injunction that respect be given to those who sit on “Moses seat” (Matthew 23:2), (3) the reference Paul made to the rock that followed the Israelites during their 40 year sojourn in the desert (I Corinthians 10:4), (4) the confrontation between the archangel Michael and Satan over Moses’ body (Jude 9), and Paul’s knowledge of the names of the Egyptian magicians (Jannes and Jambres) who opposed Moses (II Timothy 3:6-8). The above references show that the New Testament writers did not apply the principle sola scriptura to the Old Testament. The New Testament writers willingness to draw upon the Jewish oral tradition that paralleled the Jewish Scripture can be seen as evidence against sola scriptura.

The closest we can find to a blanket condemnation of tradition is in Colossians 2:8 where Paul writes:

See to it that no one takes you captive through hollow and deceptive philosophy, which depends on human tradition and the basic principles of this world rather than on Christ.

Here Paul criticizes the false teachings not because they are based on tradition per se, but because these traditions were not based upon Jesus Christ. Furthermore, anyone who wishes to use this verse to argue that Paul condemned all traditions must reconcile this verse with other verses by Paul that spoke favorably of tradition (e.g., II Thessalonians 2:15).

The Traditions of Modern Evangelicalism

Ironically, however, modern Evangelicalism does in fact have many traditions. Many Evangelicals equate “tradition” with the Christmas tree, but “tradition” is more than that: it is the way we do worship; the way we define church government; the way we understand Scripture; and the way we do theology. These traditions are not peripheral to Evangelicalism, they play an important function in the maintenance of the distinctive Evangelical sub-culture.

What is really ironic is the fact that many of these Evangelical traditions are very recent developments. The altar call where people are invited to come forward and give their life to Christ has its source in the sinners bench which first began in the early 1800s on the American frontier. The popular evangelistic crusade by Billy Graham has its roots in earlier crusades led by Billy Sunday and D.L. Moody in the 1800s. Phrases such as “deciding for Christ,” “personal relationship with Christ,” “making a personal commitment to Christ,” are novel extra-biblical ways of describing how to become a Christian. From the standpoint of historic Christianity what is so striking about modern Evangelicalism is the way it has divorced evangelism from the sacrament of baptism and membership in the Church.

Another tradition is the Sunday School. The Sunday School is just over a hundred years old. What began in Victorian England as an outreach to the lower classes ended up as one of the pillars of the Evangelical subculture. Today Evangelicals cannot imagine a church without a Sunday School. What is so striking about the Sunday School is how it reinforces the didactic qualities of the Protestant church. Historically the center of Christian worship was the Eucharist, not the sermon. When one considers the strong emphasis on the sermon and the infrequent practice of Holy Communion in many Protestant churches, it becomes apparent how Protestantism has developed a new tradition of worship with no historical precedent.

Holy Communion is another area where Evangelicals have incorporated recent customs and practices that deviate from the historic Christian faith. Widespread among Evangelicals is the belief in the bread and the wine being purely symbolic. This is a significant break from the early Church, the medieval catholic Church, the Orthodox Church and the major Protestant Reformers; all of them in one way or another affirmed the real presence in the Eucharist. Another change has been the widespread use of grape juice instead of wine. Along with this was the change in the way the communion elements were distributed. Where the historic pattern has been for people to come forward to receive Communion, the elements are brought forward by the servers on trays and passed along the pews. Thus, the Evangelical practice of Holy Communion is an example of a striking departure from the historic pattern of worship.

Evangelicalism’s Debt to Holy Tradition

Despite their rejection of Holy Tradition, Evangelicalism is heavily indebted to Holy Tradition. When Evangelicals accept the twenty seven books of the New Testament as canonical, they are in effect accepting the decision of the Sixth Ecumenical Council. When Evangelicals affirm that Jesus Christ is fully God and fully human they are in effect accepting the decisions of the Council of Nicea and the Council of Chalcedon. When they affirm their belief in the Trinity, one God who is Father, Son and Holy Spirit, they are accepting the way the early Church prayed to God in its liturgy. By their very use of the word “Trinity” the Evangelicals show themselves to be inheritors of the theological traditions of the early Church. Evangelicalism’s indebtedness to Holy Tradition can be seen in their insistence on worshiping on Sundays and not on Saturdays as do the Seventh Day Adventists and their strong pro-life stance against abortion.

Part IV. Paradigmatic Differences

Orthodoxy and Protestantism operate from different paradigms which results in radical differences in the way they do theology and construct church order. Scientists rely on paradigms to organize and interpret their data (see Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions). For example, before Copernicus made his famous discovery, many thought that the sun revolved around the earth and not the other way around. The paradigm shift from a geocentric model to a heliocentric model marked a major advance in astronomy. Paradigms are like lenses through which we see and interpret the world around us. A critical awareness of paradigms can help us appreciate the way we understand our data and why our conclusions differ from others even if we both share the same data base.

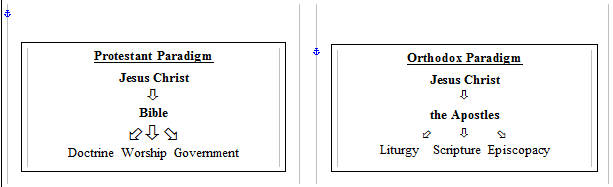

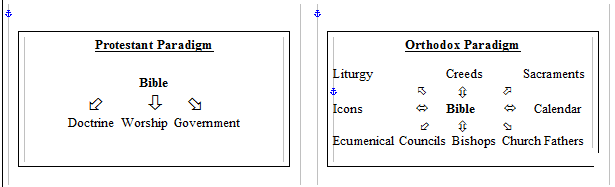

One of the major differences between Orthodoxy and Protestantism is their source for faith and practice. The Orthodox Church believes that Christ committed a body of teaching and practices to his apostles and authorized them to pass this tradition on to the nations. The Orthodox Church sees the New Testament as the written record of the teachings of Christ and his apostles, the Liturgy as continuing the pattern worship that Jesus taught his disciples, and the office of the bishop as a continuation of Jesus’ formal teaching office. For the Orthodox Christian it is possible to access the life and teaching of Christ through the Church, the recipient and guardian of Holy Tradition. While Protestantism would agree with Orthodoxy that Christ committed a body of teaching and practices to his apostles, it believes that the life and teachings of Christ can only be accessed through the New Testament. All other means are suspect or of limited value. On the basis of sola scriptura many Protestants seek to ground their theology, worship, ethics, and church government upon the Bible and nothing else. This exclusion of extra-biblical sources is a more extreme stance among Fundamentalists and popular Evangelicals. Protestants belonging to the mainstream Reformation, while open to extra-biblical sources, affirm the supremacy of Scripture over other sources of doctrine and practice.

Diagram: Source of Faith and Practice

These differences between Protestantism and Orthodoxy arise from their different ways of understanding church history. The Protestants see church history as discontinuous: there took place a break or a “Fall” in which the early church strayed into heresy, corruption, and formalism soon after the Apostles died. Christianity then entered into the Dark Ages until the Martin Luther and the Protestant Reformers rediscovered the pure Gospel and restored the New Testament Church as described in the Scripture. This kind of outlook renders church history suspect on two grounds: (1) learning from church history would undermine the principle “the Bible alone” and (2) relying on church history is to rely on a church that had fallen from the pristine purity of the New Testament Christianity into corruption and decay.

The Orthodox Church, on the other hand, has a continuous view of church history. It believes that the Holy Spirit continued to work actively in the Church even after the apostles passed. It does not differentiate between the first century, in which the apostles lived, from the following centuries. This continuous view of church history is based upon Christ’s promise that the Holy Spirit would continue to guide the Church (John 14:26) and upon Christ’s promise that the Church would be preserved against the gates of hell (Matthew 16:18). For Orthodoxy there was no break or disjuncture in church history. This is because the Orthodox Church has kept Holy Tradition without change. Thus, because there was no “Fall,” there is no need to rediscover the Gospel, neither is there a need to restore the New Testament Church for the Orthodox Church is the same church as the New Testament Church.

Diagram: Single Point vs. the Matrix

One way to describe the differences is to liken Protestantism to a single point and Orthodoxy to a matrix. For Protestants the Bible is the sole source for faith and practice. For the Orthodox Church the source of faith and practice is Tradition with a capital “T” which consists of the Bible, the Liturgy, the Sacraments, the Ecumenical Councils, and the Church Fathers all of which taken together form an interlocking and internally consistent matrix.

In the Orthodox matrix paradigm the various components of Holy Tradition form a singular coherent entity. Scripture is not subordinated to Tradition but is integrally linked to the other parts of Tradition. This means that the Bible cannot but agree with the other components of the tradition. (For example, Protestants would not put the Gospels over the Pauline epistles but see both as integral to the New Testament canon.) The Orthodox Church has several safeguards in place to prevent any hermeneutical chaos from distorting or mutating the Christian Faith: the bishops, the Church Fathers, the Liturgy, the Ecumenical Councils, and the Nicene Creed. Thus, the Orthodox matrix paradigm provides a stable framework because the various components of Tradition reinforce and regulate each other.

One of the troubling aspects of the Protestant single point paradigm is the fact that Scripture cannot be separated from the interpretation of Scripture. If one’s understanding of Scripture changes, then one’s faith and practice will likewise change. This makes for a rather tenuous and unstable basis for faith and practice. This can be seen in the bewildering variety of Protestant denominations that have come about as a result of people interpreting the Bible in different ways and being unable to reconcile their differences. This raises the conundrum of how so many different readings can emerge while the text remains unchanged. The first major division took place as early as in 1529 at the Marburg Colloquy where the Protestant Reformers were split over how to interpret the words of Christ: “This is my body.” It is quite unsettling that Protestantism’s first division took place within its first decade of existence.

The principle “Scripture interprets Scripture” is nonsense if taken literally. It would be like saying: Scripture reads Scripture. The Bible is read by people who at the same time interpret what they are reading. What the Protestant Reformers meant here was that Scripture is internally consistent in meaning. However, the Marburg Colloquy brought out the fact that there are some passages that can be understood in quite different ways and which do not provide any further means for ascertaining the precise meaning of the contested text.

V. Contending for the Faith

Jude 3 contains one of the strongest refutation of Protestantism. Ironically, this is one of Evangelicalism’s favorite which they use to defend the fundamentals of the Christian faith:

Dear friends, although I was very eager to write to you about the salvation we share, I felt I had to write to you and urge you to contend for the faith that was once and for all entrusted to the saints.

There are three aspects of this verse that is pertinent to our discussion: (1) the use of the definite article in the phrase “the Faith”, (2) the clear reference to the traditioning process “entrusted”, and (3) the phrase “once and for all” (απαξ or hapax). The use of the definite article in “the Faith” is significant for it refers to an already existent specific body of doctrines and practices. This indicates that the Christian Faith was the result of divine revelation, not something to be discovered by theological research or mystic gnosis or the result of doctrinal evolution.

Also significant is the fact the Greek word hapax “once for all” which was used to condition the traditioning process paradotheisee “entrusted” or “handed over.” The word hapax is the same Greek word used in Hebrews 9:28 in reference to Christ’s unique once for all time redeeming death on the Cross. The word hapax rules out new doctrines and practices. In other words, it rules out the possibility of later revelations like the Book of Mormons or “new light yet to break forth” touted by the Liberals. It points to a fixity and permanence in the content of the Christian faith, i.e., Tradition cannot change. This implies that a historical continuity in the Christian faith must exist from the first century to the present. Doctrinal innovation is to be viewed with grave suspicion.

When one reflects on the fact that so much of Evangelical theology and practice have their roots in the nineteenth century this verse has disturbing implications regarding the viability of Evangelicalism. This verse is devastating because if the Christian Faith cannot change, then either Evangelicalism must prove doctrinal continuity with the early church or else admit that their faith is a modern innovation. Protestants attempting to trace their historical roots can go only as far back as the Protestant Reformation before they hit a blank wall. This means that Evangelicals must give serious consideration to Orthodoxy’s claim that it has kept the Faith unchanged. Orthodoxy’s claim that it has kept the Faith unchanged should not be construed to mean a static understanding of Tradition. Holy Tradition is both fixed and dynamic, much like the dynamic similarities between an acorn and a fully grown oak tree. It is not so much a fixed formula as it is the mind of Christ at work in the Church by the Holy Spirit.

For Evangelicals considering Orthodoxy, there is comfort in the fact that many of Evangelicalism’s core beliefs are compatible with Orthodoxy: the divine inspiration and authority of Scripture, the divine nature of Jesus Christ and his death on the cross for the salvation of the world, the necessity of faith in Christ for salvation, and the Second Coming of Christ. However, certain distinctive Protestant beliefs e.g., sola fide and sola scriptura, must be regarded as recent innovations, and not part of the historic Christian faith. In other words, one can continue to be an Evangelical in the Orthodox Church even if they cease to be Protestant.

But What if Scripture and Tradition Contradict Each Other?

An Evangelical friend once asked, “But what if Tradition contradicts the Bible?” To answer this question, one must ask two questions for the sake of clarity: (1) “What do you mean by ‘Scripture’?” and (2) “What do you mean by ‘Tradition’?”

First, what needs to be recognized here is the fact that when we speak of Scripture we are at the same time speaking of our particular understanding of Scripture. The Bible can be interpreted in a number of different ways, some of which are correct and others which are erroneous. In short, the so-called contradictions in reality reflect the contradiction between Holy Tradition and particular interpretations of Scripture. This then leads to the question: who has the right interpretation?

Second, what needs to be kept in mind is that when we refer to Tradition we are referring to apostolic tradition, the oral teachings the original apostles passed on to their disciples and successors (II Thessalonians 2:15, II Timothy 2:2). The agreement between written and oral tradition is based upon the assumption that what Paul wrote in his epistles would be in agreement with what his first century listeners heard from his mouth. Critical to the Orthodox understanding of the coinherence of written and oral tradition is the assumption that the early Christians and later generations of Christians faithfully committed to memory the apostles teachings. The “fall of the church” theory so widely assumed in Protestant circles rest on two assumptions: (1) that II Timothy 2:2 was never put into practice and (2) there took place a massive memory loss in the early Christian community.

The Orthodox Church rejects the fall of the church theory. This is because the Church has several safeguards in place that ensures the right interpretation of Scripture: the Liturgy, the historical linkages to the apostles through the bishops, the theological consensus in the Ecumenical Councils, and the Church Fathers. Because Scripture as well as the other components of Tradition share a common apostolic source, they can be expected to be in agreement with each other. Thus, Orthodox interpretations will agree with Tradition, whereas erroneous and heretical interpretations will contradict Tradition.

The question I would pose to Protestants is this: On what basis can Protestants claim to have a superior interpretation of the Bible? What advantage do modern Protestant Evangelicals have over the early Church Fathers? And I would add, Can you claim that your interpretation is the Protestant interpretation? Furthermore, how can Evangelicals be so concerned about the alleged contradictions between the Bible and Tradition when there are so many rival interpretations among Evangelicals that contradict each other. Protestantism is theologically incoherent being split as it is into so many different denominations unable to come together in agreement over issues of faith, sacrament, worship, and church governance.

When one studies the early Church one is struck by the remarkable theological unity among the early Church Fathers — Irenaeus of Lyons, Ambrose of Milan, Pope Leo of Rome, Pope Gregory of Rome, Athanasius of Alexandria, John of Damascus. The fact there was a common faith that spanned across the vast Roman Empire as well as over several centuries stands in stark contrast to Protestantism’s short history.

One early witness to the doctrinal unity of the early Church was Irenaeus of Lyons. In Against the Heretics he wrote:

Having received this preaching and this faith, as I have said, the Church, although scattered in the whole world, carefully preserves it, as if living in one house. She believes these things [everywhere] alike, as if she had but one heart and one soul, and preaches them harmoniously, teaches them, and hands them down, as if she had but one mouth (Richardson 1970:360).

Evangelicals troubled by Protestantism’s disarray might find Irenaeus’ description of the unity of the faith attractive, but at the same time they may find his emphasis on there being only one Church disturbing. The unity that Irenaeus refers to is not an invisible spiritual unity (like the unity many Evangelicals prattle about) but a tangible and visible unity. He wrote:

But as I said before, the real Church has one and the same faith everywhere in the world (Richardson 1970:362).

Evangelicals who are accepting of denominational differences will find Irenaeus’ statement very disturbing because it raises the question: Do I belong to the true Church? Irenaeus’ writings challenges modern day Evangelicals to choose between their own local church or denomination, and the Eastern Orthodox Church which claimed to be the “one holy catholic and apostolic church.”

To return to my friend’s question: “But what if Tradition contradicts the Bible?,” my answer is: Tradition will never contradict the Bible. This is based on oral and written tradition having the same apostolic source (II Thessalonians 2:2) and the faithful transmission of the apostles’ teachings to subsequent generations (II Timothy 2:2). Apostolic tradition is guaranteed by Christ’s promises that he would give the Holy Spirit to guide the Church into all truth (John 14:23, 16:13) and that the Church would be preserved in the face of satanic opposition (Matthew 16:18). It is also based upon Paul’s description of the Church as the “pillar and foundation of truth” (I Timothy 3:15). The opposite corollary is likewise true: whatever contradicts Scripture cannot be Tradition. The key here is what we mean when we say “Tradition.” Here we are referring to apostolic tradition. If Holy Tradition is indeed biblical (as has been shown in this paper), then Evangelicals should have very little problem accepting the Orthodox Church’s teaching on Tradition and Scripture.

The Irony of Sola Scriptura

One great irony of the Protestant Reformation is that its anti-traditionalism would become a tradition of Protestantism (Pelikan 1984:11). The inescapable fact is that every church group belongs to a particular tradition. When a Baptist church claims to hold to the baptist distinctives, they are really speaking of faithfully adhering to the Baptist tradition. The choice that lies before every Evangelical is whether they will hold to a tradition that is for the most part only two hundred years old or receive Holy Tradition, which has been kept intact by the Orthodox Church for two thousand years.

Shortly before I joined the Orthodox Church, my friend Steve, a Baptist minister, warned me: “Now you shouldn’t add to the Bible.” In light of the above discussion, Steve’s warning is quite ironic, for if sola scriptura cannot be found in the Bible then Protestants are guilty of adding sola scriptura to the Bible. Furthermore, if the Bible is the bottomline for Evangelicals and if Holy Tradition is biblical then the real Evangelical is one who belongs to the Orthodox Church.

Robert Arakaki

REFERENCE

Ahlstrom, Sydney E. 1975. A Religious History of the American People. Volume 2. Garden City, New York: Image Books.

Arnold, Eberhard. 1970. The Early Christians in their Own Words. Translated from Die Ersten Christen nach dem Tode der Apostel, 1926. Printed 1997. Farmington, Pennsylvania: Plough Publishing House, 1970.

Basil the Great. 1980. On the Holy Spirit. Introduction by David Anderson. Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

Eusebius. 1965. The History of the Church: From Christ to Constantine. G.A. Williamson, translator. New York: Penguin Books.

Hahn, Scott and Kimberly. 1993. Rome Sweet Home: Our Journey to Catholicism. San Francisco: Ignatius Press.

Kuhn, Thomas S. 1970. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Second Edition, Enlarged. International Encyclopedia of Unified Science: Volume 2 Number 2. First published 1962. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Noll, Mark A. 1994. The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Pelikan, Jarsolav. 1984. The Vindication of Tradition. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Richardson, Cyril C., ed. 1970. Early Christian Fathers. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc.

Williams, D.H. 1998. The Search for Sola Scriptura in the Early Church. Interpretation: A Journal of Bible and Theology Vol. 52 No. 4 (October): 354-366.

Wycliffe Bible Translators. 2000. Amsterdam 2000. In Other Words. Vol. 26, No. 3 (Winter): 18-21.

Coming Soon: Contra Sola Scriptura (3 of 4).

Recent Comments