Protestantism’s Fatal Genetic Flaw: Sola Scriptura and Protestantism’s Hermeneutical Chaos

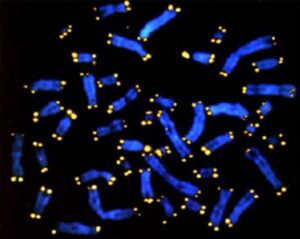

Chromosomes with Telomeres

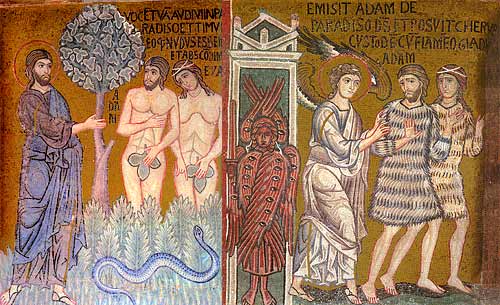

During the 1960s a book Double Helix came out that described Francis Crick and James Watson’s discovery of the double helix structure that made up DNA. This was a landmark discovery for it enabled scientists to understand how living organisms were able to replicate themselves from generation to generation. DNA functioned as a unique blueprint for each human being: a set of instructions about the color of our eyes, the shape of our nose etc. In the 1980s scientists discovered the presence of telomeres, little bits of DNA located at the end of the chromosome chain. Telomeres function to keep DNA intact each time a cell splits in half — very much in the same way that the little plastic ends of a shoe lace keeps the laces from unraveling (See Gorman 1998).

The same principle applies to social organizations. Organizations, like living organisms, need a set of core values in order to reproduce. The worldwide franchise of McDonald’s hamburgers is a good example of consistent social reproduction. The process of social reproduction is based upon the repetition of concepts and practices constitutive for the group. In sociology this has been referred to as “recipe knowledge” (Berger and Luckmann 1967:65). In classical theology these core beliefs are known as the regula fidei or Holy Tradition (#1). For the first thousand years Holy Tradition enabled the Church to be united in faith and worship.

In contrast to the early Church, what is so striking about Protestantism is its inability to consistently reproduce itself. The sheer number of mutations in Protestantism’s 450 years, in contrast with the stability and unity of the first 1000 years of Christianity, is staggering. It is as if over time Protestantism does not reproduce itself, but rather mutates into a confusing array of motley beliefs. Peter Berger observes:

Revisionism is possible in all traditions, but Protestantism has, as it were, a built-in revisionist tendency (1979:128).

It is as if McDonald’s franchisees began to argue over the menu, changing the menu from week to week, and then broke up into rival hamburger joints all competing against each other.

Using the analogy of DNA and the telomeres, Protestantism’s inability to consistently reproduce itself — its tendency to fragmentation and theological innovations — seems to mirror some kind of unraveling of its genetic code. In this paper I argue that it is sola scriptura that is the underlying cause of Protestantism’s hermeneutical chaos. In the early Church the Bible and Holy Tradition were seen as forming a unified whole. Holy Tradition safeguarded the Bible by providing a proper and consistent interpretation — very much in the same way telomeres ensured consistent reproduction by protecting the integrity of the DNA. In contrast to the patristic regula fidei, the Protestant Reformers proclaimed Scripture alone to be the “only rule of faith and practice” (Osterhaven 1984:962). Scripture became detached from Tradition. When it discarded Holy Tradition as binding and authoritative, Protestantism threw out the basis for a consistent and proper reading of Scripture (#2). Thus, Protestantism’s sola scriptura has resulted in its DNA code (the Bible) being stripped of its telomeres (Holy Tradition).

Methodologically, in this paper I take a sociology of knowledge approach to understanding sola scriptura. It complements my earlier critiques, one which addressed sola scriptura from a biblical exegesis approach and another which took a historical/genealogical approach.

Sola scriptura resulted in the rise of a host of rival interpretations of the Bible and no effective means of arbitrating these differences. It is this that constitutes Protestantism’s fatal genetic flaw. It is ‘fatal’ in the sense that Protestant Christianity, lacking the capacity to consistently replicate itself, mutates into ever more bizarre and aberrant forms that bear little if any resemblance to the original Reformation churches (to say nothing of the early Church). It is ‘fatal’ in the sense that Protestant Christianity being broken up into rival camps is unable to present a unified witness to the world. And, it is ‘fatal’ in the sense that being cut off from its past Protestantism has lost its sense of direction to guide it into the future.

The Faultlines of Protestantism

Martin Luther at the Diet of Worms

Martin Luther’s defiant “Here I stand” at the Diet of Worms struck the Roman Catholic Church like a bolt of lightning. It shattered the religious unity that held together medieval European society and it gave rise to a very different social milieu. Luther’s defiance of the collective authority of the Church on the basis of Scripture constitutes a watershed event in the history of Christianity. Luther’s paradigm shift created a religious community whose hermeneutics was detached from Tradition, i.e., Tradition in the form of historical continuity and conciliar authority.

At the core of the Protestant Reformation are two principles: sola scriptura — Scripture alone; and ecclesia reformata sed semper reformanda — the church reformed yet always reforming. The Reformers believed that sola scriptura would provide them with the means by which they would reach their goal of a church reformed. The “sola” in sola scriptura does not exclude all other authorities but considers them “helps and assistants, human and fallible, not as divine authorities” (Ramm 1970:1, see also Mathison 2001). The principle sola scriptura contained within it a certain paradoxical double-edged quality that the original Reformers had to struggle with. Nathan Hatch observes:

Protestants from Luther to Wesley had been forced to define very carefully what they meant by sola scriptura. They found it an effective banner to unfurl when attacking Catholics on the right, but always a bit troublesome when common people began to take the teaching seriously (1982:61).

Sola scriptura also created a hermeneutical dilemma for Protestants. Jaroslav Pelikan notes that the theology of conservative Protestants rests upon a somewhat paradoxical basis, being both radical and conservative at the same time.

The supporters of the sole authority of Scripture, arguing from radical hermeneutical premises to conservative dogmatic conclusions, overlooked the function of tradition in securing what they regarded as the correct exegesis of Scripture against heretical alternatives (1971:119).

Protestantism has long functioned on the basis of an implicit regula fidei which has helped it maintain a certain degree of stability and continuity. But at the same time the implicit nature of Protestantism’s regula fidei made it vulnerable to external pressures from society.

Luther vs. Zwingli

The dysfunctional character of sola scriptura became manifest almost from the start. One of the earliest schisms in Protestantism took place over the Lord’s Supper. Zwingli believed that the Lord’s Supper was just a memorial, whereas Luther believed in the real presence of Christ in the bread and wine. This controversy over the real presence between Luther and Zwingli at the Marburg Colloquy in 1529 was basically a split over hermeneutics. The failure of the two reformers to reach a shared understanding of Christ’s words, “This is my body,” presaged the hermeneutical chaos that would plague Protestantism.

The Protestant Reformers sought to reform the Catholic Church, but the unintended consequence was the shattering of church unity. The initial Protestant Reformation was split into four major camps: Lutheran, Reformed, Zwinglian, and Anabaptist. A short time later the Church of England with its unique Catholic/Protestant hybrid of via media emerged as a result of Henry VIII’s break from Rome. One of the tragic consequences of the Protestant Reformation was the religious division of Europe and the religious wars between Protestants and Catholics. The religious wars took a heavy toll on Europe until the adoption of the principle of cujus regio, ejus religio at the Peace of Augsburg in 1555 (#3). This arrangement had several consequences: (1) it gave recognition to the new religious pluralism in Germany, and (2) it continued the practice of linking the church with the state. This arrangement while supporting religious pluralism also gave it a measure of structural stability in Europe. Later when Christianity became disestablished in America one of the key factors that inhibited change in European churches was removed giving American churches their distinctive tendency for innovation and fragmentation.

The Rise of the American Church

Christianity in America was significantly influenced and shaped by the English Reformation, especially Puritanism, of the mid 1600s (Ahlstrom Vol. I 1975:169). The instability caused by the religious upheavals in England hindered the government’s regulation of migration to the New World. This resulted in large numbers of religious dissenters emigrating, giving rise to a social order based on a radical break from the past. While the Puritans affirmed sola scriptura, they radicalized it through the regulative principle which stipulated only what was mandated by Scripture was allowable for worship (Ahlstrom Vol. I. 1975:170). They also pursued moral purity, i.e., individual and general conformity to the ethical teachings of the Bible. Another way that Puritanism radicalized the Reformation was its emphasis on conversion narratives. Unlike Anglicanism and Catholicism, the Puritans did not believe that all who resided in a given parish should be full church members. Because the “pure” church was comprised of the elect only those who could bear witness to a personal experience of divine grace were allowed into full membership (Ahlstrom Vol. I 1975:194). This emphasis on subjective grace would give rise to the Half-way Covenant controversy in the late 1600s and the Great Awakenings of the mid 1700s and the early 1800s.

When the radical exegesis entailed in the Puritan regulative principle and the subjectivity of the conversion testimony are brought together, the foundation is laid for what Mathison labeled solo scriptura. Unlike the classic Reformation doctrine sola scriptura which allowed for creeds, ceremonials, and other extra-biblical practices even while the primacy of Scripture is affirmed, the innovative doctrine solo scriptura shunned extra-biblical practices. The radical subjectivity in Puritan spirituality also laid the groundwork for a highly individualistic approach to salvation that: (1) denigrated membership in established churches, (2) promoted an independent reading of the Bible without the aid of an educated clergy, and (3) allowed for the founding of churches free of the “traditions of men.” In short, the Reformers adherence to the normative principle of worship — what Scripture does not prohibit is permitted — allowed for the retention of historical memory. However, with the widespread acceptance of the regulative principle of worship — what Scripture does not enjoin is prohibited — combined with a radically subjective and individualistic understanding of conversion, the Protestant principle of sola scriptura underwent modification resulting in a genetic mutation: solo scriptura.

America in the 1800s was one vast laboratory for social and religious experimentation. With the winning of the Revolutionary War and the establishment of the Constitution there was a widespread sense of optimism as the new era began. The constitutional separation of church and state was a momentous development, marking a break from the traditional state-church pattern found in Europe. In this new situation the two fundamental tenets of the Protestant Reformation — sola scriptura and ecclesia reformata sed semper reformanda — achieved a new level of intensity. Sola scriptura degenerated into an unmediated reading of Scripture to the exclusion of Tradition, the Papacy, or the Creeds. Under the influence of Restorationaism ecclesia reformata sed semper reformanda led to radically new forms of church structures as people sought to recreate the idealized primitive church (#4).

Frontier Revival

Sola scriptura took on new meaning out on the frontier where the pioneers attempted to leave behind their past and start all over again from scratch (#5). Many endeavored to be Christian with only the Bible guiding them. Out on the frontier a revivalist and populist Christianity emerged with a strong streak of anti-traditionalism. The revivalists called upon people to flee from religious tradition and traditional learning. The Restorationists attempted to read the Bible alone apart from all other sources in the belief that by doing this they would be able to replicate the early church. This gave rise to Protestants who had no knowledge of John Calvin or any of the other great Protestant Reformers.

The American frontier also gave rise to the “believers’ church” — the church as a voluntary association of like-minded individuals. The believers’ church is very American and very modern. It is strongly influenced by Lockean liberalism which makes the individual the most important social unit. The believers’ church diverged significantly from the historic understanding of the catholicity (universality) of the Church. Unlike the state church in Europe which enjoyed a stable monopoly, the disestablished churches in America were forced to compete for adherents. This gave rise to a kind of religious entrepreneurialism (#6).

Another innovation was the rise of denominations. Denominations began as groups of people gathered around the interpretation of a particular preacher or bible teacher. As more conflicting interpretations arose, more new denominations were formed. The growing number of denominations mirrored the growing doctrinal chaos of American Protestantism. Denominational specialization can be seen as embodying not only particular interpretations of the Bible but also as creating adaptive niches in a competitive religious market. The rise of denominationalism shattered the classical parish system. The individual congregation no longer mirrored the whole spectrum of society, only a part of it (Ahlstrom Vol. II 1975:323).

As America became an urban society the local parish underwent a significant change in nature. Where before the local church had only two primary functions: worship and the regulation of the morality of its members, American Protestant churches underwent structural differentiation becoming “social congregations” with diverse goals and manifold activities (Cherry 1995:39). Urban churches began to sponsor Sunday schools, concerts, church socials, sewing circles, soup kitchens, employment bureaus, libraries etc. All this laid the groundwork for the rise of a spiritual marketplace in which the local church became the purveyor of spiritual goods and the individual Christians as the consumer. The church became a kind of department store that attempted to address a wide range of needs — educational, entertainment, rehabilitative — in addition to the spiritual.

Another major innovation was revivalism’s emphasis on the personal conversion experience which radically redefined how people understood faith. Where faith had been understood as assent to a certain body of doctrine, it now took on a more subjective and emotional sense. This new understanding of faith resulted in widespread indifference to doctrine. Ahlstrom writes:

Because revivalists so often addressed interdenominational audiences, moreover, nearly all doctrinal emphases tended to be suppressed, not only by famous spellbinders, but by the thousands upon thousands local ministers and now-forgotten regional itinerants. Gradually a kind of unwritten consensus emerged, its cardinal articles being the infallibility of the Scriptures, the divinity of Christ, and man’s duty to be converted from the ways of sin to a life guided by a pietistic code of morals. Revivalism, in other words, was a mighty engine of doctrinal destruction (Ahlstrom Vol. II 1975:321).

The radical emphasis on individual piety effectively undermined the notion of the Puritan Commonwealth and the basis for classic Calvinism’s predestination (Ahlstrom Vol. II 1975:320-321).

The 1800s was a formative period for the American Protestant church. It was during this time that many of the distinctive features of Evangelicalism have their origins. The altar call, the evangelistic rallies and revival meetings all originated in the 1800s. Dispensationalism with its emphasis on the Second Coming of Christ and a literal millennium became widely popular displacing the long-standing amillennial and postmillennial beliefs of Protestantism (#7). Also influential was the Holiness Revival with its emphasis on perfectionism (#8) and the separatistic “come-outism.” The temperance movement led many churches to use grape juice in the place of wine in Holy Communion (a practice with no historical precedent in church history).

Although Evangelicalism claims to be Protestant in origin, much of it roots can be traced to the 1800s. This was a period when numerous innovations were introduced that distanced Evangelicalism from its roots in the Protestant Reformation. The startling transformations in American Protestantism can be considered a case of ecclesia reformata sed semper reformanda gone amok.

Protestantism Unravels

Even more radical changes were to enter American Protestantism towards the end of the nineteenth century. It was here that I found the roots of the tragic conflict between the Liberals and Evangelicals in my former denomination, the United Church of Christ (UCC). This conflict mirrors Protestantism’s twofold interaction with modernity (#9). Using the analogy of the double-helix structure of DNA, I would argue that under the pressures of modern culture Protestantism’s internal genetic code began to split apart into two separate rival strands: Evangelicalism and Liberalism. Both are essentially syncretistic adaptations to modernity. Where Liberalism is the outcome of Protestantism’s interaction with high culture and the Enlightenment, Evangelicalism reflects Protestantism’s interaction with popular culture and capitalism (#10). This resulted in more historic forms of Protestantism becoming a forgotten remnant relegated to the margins of the religious market. Protestantism’s susceptibility to modernity is due to its being deeply rooted in modernity (#11).

Liberalism’s orientation to high culture can be seen in the liberal seminaries’ attempt to adapt theology to “higher criticism” originating from European universities. It can also be seen in Liberalism’s close relationships with political liberalism. Evangelicalism’s orientation to low culture, or popular culture, can be seen their openness to adapting worship to popular styles of entertainment, the ease with which they applied modern marketing techniques to their evangelistic campaigns, as well as their often cozy relationship with political conservatives. This orientation to popular culture and modern capitalism can be found going back to D.L. Moody (Moore 1994:184 ff.). The commodification of religion affected not just the conservatives but the theological liberals as well (Moore 1994:209).

Liberalism and Evangelicalism held contrasting attitudes towards modernity. One openly embraced it while the other shunned it. Liberalism’s infatuation with modernity can be seen in the blatant motto adopted by the World Council of Churches in the 1960s: “The world sets the agenda for the church.” Evangelicalism and its Fundamentalist predecessors hold to a more suspicious view of modernity. Despite its denunciation of modernity Evangelicalism’s pragmatism has unwittingly allowed itself to be shaped by the marketing mentality of modern capitalism. Thus, although Evangelicals and Liberals view each other as enemies, both sides are actually closely related.

The Rise of Liberalism

The rise of Liberalism in America can be traced to the Industrial Revolution and to the German Enlightenment. The Industrial Revolution wrought major changes in American society. A new economy emerged eclipsing the more traditional agricultural and crafts based economy. A new elite emerged (e.g., the Robber Barons) rivaling the older traditional elite situated on the Eastern Seaboard. Liberal Christianity emerged as an adaptive response to the shifting social landscape. Rather than take a defiant stance and beat a retreat (as did Pope Pius IX’s Syllabus of Errors), Protestantism in America embraced the new social reality. This syncretistic adaptation was designed to enable the mainline denominations to maintain their standing in society rather than be ostracized and marginalized.

In the early period of American history higher education was centered around the divinity school. Many of America’s premiere institutions of higher learning like Harvard and Yale were originally established for the training of an educated clergy. However, all that changed with the Industrial Revolution. Industrial capitalism required a new kind of university, one that was built upon the natural sciences and social sciences. American universities patterned themselves after the German model. They adopted the principle of academic freedom. The tenure system was adopted which enabled professors to openly criticize traditional beliefs. Autonomous departments were created and preference given to the natural sciences. The divinity schools fell by the wayside as America raced ahead to become the world’s leading economic and military power.

The Industrial Revolution did not change the seminaries directly, but it created structural pressures making seminaries and churches more open to change. With the emergence of the modern university, the seminaries were in danger of becoming marginalized. Conrad Cherry’s Hurrying Toward Zion (1995) provides an insightful analysis of the Protestant seminaries struggle to find a place in the modern university. Prior to the Civil War, clergymen made up ninety percent of the college presidents, however a hundred years later clergymen would be virtually absent among college presidents (Cherry 1995:130). Another indicator of the marginalization of the American clergy was the fact that increasing numbers of clergy were receiving their education in small denominational colleges rather than the more prestigious universities and divinity schools (Cherry 1995:130). To prevent their marginalization some seminaries began to insist on their students being grounded in the natural sciences than in the humanities. Others began to insist on hiring professors trained in the higher critical methods of German scholarship.

The second key factor to the rise of Liberal Christianity in America was the German “Enlightenment.” As influential as the Industrial Revolution was, it was the introduction of new theological ideas from Germany that would transform the doctrinal landscape of American Protestantism. Theological Liberalism was in large part a university based movement, not parish based. Many of the leading theological liberals held posts at major universities: Schleiermacher at the University of Halle and University of Berlin; Hegel at the University of Berlin (#12); Ritschl at Bonn and Göttingen; Baur at Tübingen; Strauss at University of Zurich (#13); and Wellhausen at Göttingen (#14); Troeltsch at Heidelberg then Berlin; and von Harnack at Berlin (see Latourette Vol. II 1953:1120 ff.). The prestige of German scholarship was such that many of the seminary faculty in America received their degrees from Germany (Cherry 1995:297, 358 no.1).

There were a number of sociological factors that contributed to the rise of Liberalism. Seminaries that became theologically liberal tended to be located near major urban centers — the major centers of power and higher education. The first seminaries that went liberal were those had strong ties with major universities (Harvard Divinity School, Yale Divinity School, Chicago Theological Seminary). Both the seminary and the university are educational institutions which means that there is a certain affinity between them that facilitates the transmission of new ideas. Economic class was also involved. The leading seminaries at the time produced clergy for denominations whose membership came from the middle and upper classes. Adapting seminary education to the modern university setting was a pragmatic move that enabled populist denominations like Methodism make the transition from the rustic hinterlands to the middle-class urban mainstream (Cherry 1995:268). It is no surprise then that the university-based seminaries would be the principle transmitter of Liberalism.

The Rise of Fundamentalism

By the late 1800s seminaries were divided between professors who supported the use of higher critical methods and those who held to the commonsense reading of the Bible (#15). The conservatives recognizing the inherent dangers of Liberalism’s naturalism refused to revise their theologies (#16). Tensions grew until churches and even whole denominations were engulfed in controversy.

Things came to a head in the 1920s when the conservatives lost control of many denominations and were ousted by the liberals (#17). This loss was a traumatic one. Fundamentalism acquired a shrill combativeness and anti-intellectual rigidity not found among its Protestant antecedents. Joel Carpenter writes of the origins of Fundamentalism:

Fundamentalism’s intellectual legacy is at least two-sided as well. On the one hand, the movement was heir to a campaign in the late nineteenth century to repopularize the gospel, which led many evangelical leaders of Moody’s day to neglect their intellectual responsibilities. The result was a near-abdication of any voice in academe at a time when the intellectual foundations of Judeo-Christian theism were being questioned as never before. Fundamentalist leaders were caught unprepared to respond to the critiques of scientific naturalism, whether applied to natural history or the study of the Bible. They fought with rusty intellectual weapons and very often resorted to anti-intellectual ridicule or the use of disreputable ideas and theories, such as those of the young-earth creationists. They left an enduring legacy of populist intolerance of ideas that cannot be explained in layman’s terms and impatience with disciplined thinking in general (Carpenter 1997:243-244).

The price that many Evangelical schools have had to pay was high. In their attempt to preserve their theology intact, they acquired an insularity that cut them off from mainstream American culture (#18). Mark Noll gives a more sophisticated analysis of Evangelicalism’s anti-intellectualism in his Scandal of the Evangelical Mind (1994).

Fundamentalism is basically a strategy of retreat from modern culture and a self-imposed ghettoization in order to maintain theological orthodoxy. Fundamentalism is probably best described as a sub-culture of Protestants who rejected much of modern science and modern culture in their attempt to maintain their belief in the inerrancy of Scripture. It is important to keep in mind that many theological conservatives did not leave their denominational homes. Having lost the battle for the “commanding heights” of their denominations, they laid low in the pews while remaining active in the local parish or channeled their energies into parachurch ministries (See Cherry 1995:171-172).

Among the prominent social institutions of Fundamentalism were bible colleges, bible camps, and bible conferences all of which inculcated the literal reading of the Bible and disdained critical scholarship. In their retreat from mainstream American culture, the Fundamentalists established bible colleges in an attempt to create a parallel educational system untainted by the heresies of modern science: Darwinism, literary source criticism, etc. Another significant social institution of Fundamentalism was the parachurch ministry. The effectiveness of parachurch organizations lay in their being based upon highly motivated volunteers, their broad non-denominational theology, and their single-minded mission. Through the parachurch organizations — Young Life, Youth for Christ, Billy Graham Crusades, Campus Crusade for Christ, InterVarsity Christian Fellowship — Evangelicalism exerted a powerful influence on the mainline denominations at the grassroot level (#19). The parachurch organizations provided safe havens for Evangelicals enabling them to retain membership in mainline denominations while affirming their more conservative theology and spirituality.

After World War II there emerged a new spirit among Fundamentalists who rejected the earlier world rejecting stance and who believed that it was possible to combine a strong commitment to Scripture with solid scholarship. This new Evangelicalism represents an attempt to establish a via media between Fundamentalism’s rejection of modern culture and Liberalism’s embrace of modern culture. Evangelicalism’s move to a more open stance to mainstream culture is probably best captured by Richard Quebedeaux’s The Young Evangelicals (1974) and The Worldly Evangelicals (1980). George Marsden’s Reforming Fundamentalism uses the founding of Fuller Seminary for a detailed case study analysis of the transition from Fundamentalism to Evangelicalism. However this venture was a gamble that one can retain one’s Evangelical identity while engaging with modern culture. The mixed results of the new Evangelicals’ embrace of modernity can be seen in The Coming Evangelical Crisis (John Armstrong, ed., 1996).

Post-Modernity’s Threat to Protestantism

In recent years Western culture has made a shift from modernity to post-modernity. Modernity is based upon the assumptions of the superiority of scientific reason, the possibility of objective knowledge and the unity of knowledge. Post-modernism is hostile to claims of objective knowledge, universal truth, and moral absolutes (#20). The shift to post-modernity probably began in the 1960s and 70s as American society became deeply divided politically and culturally over the Vietnam War, Watergate, and rock-n-roll. An anti-authoritarian attitude emerged suspicious of political and cultural authorities. Popular confidence in the goodness of science was shaken by the threat of a nuclear holocaust or ecological disaster from pesticide poisoning. In the 1980s another shift towards post-modernity took place as people began to lose an unquestioning respect for modern science. People were unsettled by shifting and conflicting findings by scientists: e.g., Saccharine has been found to cause cancer, saccharine has been found not to cause cancer. Revelations about how the tobacco industry has sponsored “scientific” research to advance its corporate interests has made many cynical about the objectivity of scientific research.

It would be claiming too much to say that America has left behind modernity. It might be more accurate to say that American society has entered into a post-modern situation marked by an increasingly diverse and fragmented cultural landscape and the passing of a public sphere dominated by Protestantism (#21). The decline of denominationalism represented a clearing of the deck that allowed for a rearrangement of the religious market (Wuthnow 1988:11). The anti-authoritarian atmosphere of the 1960s took a toll on the religious sector. Confidence in traditional religious values weakened and religious experimentation became more common. An American student would try on different religious personae — a Presbyterian one year, a Buddhist the next, then a practitioner of Transcendental Meditation (Cherry 1995:113). Protestant seminaries were finding increasing numbers of seminarians were uncertain about their vocational goal and in seminary to “find themselves” (Cherry 1995:113).

The transition to post-modernity can be seen in the shifts in the location of truth in public space. In the Puritan commonwealth the public truth was located in the pulpit, i.e., the minister’s preaching of Holy Scripture. With the Industrial Revolution the locus of truth shifted to modern science. Now public truth is located in the university, i.e., the university classroom or the scientist working in his laboratory. The modern “It has been scientifically proven ….” superseded the pre-modern “The Bible teaches us ….” More recently public truth has shifted to the television and mass media, i.e., to the celebrity. A recent Christianity Today article describes how Oprah Winfrey, one of America’s leading talk show celebrities, has come to be one of America’s spiritual leaders (see Taylor). In this post-modern situation, the celebrity outranks the Christian minister and the modern scientist as cultural authorities. The irony is that Evangelicalism has paved the way with its practice of using sports heroes and other celebrities to share the gospel message rather than the ordained minister. Post-modernism constitutes a major challenge against Protestantism — whether Liberal or Evangelical. The emergence of a post-modern and a post-Christian society threatens to render Protestantism culturally irrelevant.

The Demise of Liberalism

Liberalism functioned as well as it did largely because of its ability to adapt to the cultural assumptions of modernity. Yet Liberal Christianity paid a heavy price for its syncretistic embrace of modern culture. After enjoying a brief religious boom in the 1950s, mainline denominations suffered significant membership losses from the 1960s to 1990s. Membership losses have been attributed to several factors. One has been the attempts by liberal theologians in the 60s to transform the church into a vehicle for challenging social injustice. These attempts to politicize the local church alienated many lay people causing many to leave (Hadden 1969). The decline of mainline denominations has also been attributed to the loss of its youth who find it unappealing or irrelevant, preferring Evangelicalism instead (Hutcheson 1981:47 ff.).

The recent decades have been just as cruel to the mainline seminaries. Membership losses in the mainline denominations have had a serious impact on the funding of denominational programs. In the 1990s the financial base for seminaries shrank to the point of putting them at risk. Surprisingly many of the seminary leaders saw cultural relevancy as the greatest challenge they had to face, not finances (Cherry 1995:289-292).

The attempts by mainline seminaries to avoid marginalization by adapting itself to modernity has by and large been a failure. Under the auspices of modern scientific research, the modern universities sought to replace the traditional seminaries with departments of religious studies (#22). Some major seminaries even faced the danger of extinction. The Harvard Divinity School in the 1940s and 50s was in danger of being shut down and having its resources transferred to the department of religion (Cherry 1995:276). Thomas Oden, a professor at a liberal Methodist seminary, writes: “The seminary that weds itself to modernity is already a widow as we enter the era of post-modernity” (1994).

Liberalism’s attempts to avoid marginalization through conformity to modern thought has backfired. Liberal theology, for all its attempt to influence society, has remained an elite ideology. It never succeeded in its attempt to reshape the theological outlook of the laity. There is a certain irony in the fact that public opinion polls in the 1980s found the majority of Americans still holding to beliefs that Henry Emerson Fosdick would have found backward and unenlightened (Cherry 1995:172). Thomas Oden made a similar finding:

Finally my students got through to me. They do not want to hear a watered-down modern reinterpretation. They want nothing less than the substance of faith of the apostles and martyrs without too much interference from modern pablum-peddlers who doubt that they are tough enough to take it straight (1990:14-15).

With the emergence of post-modernity Liberalism may suffer a double tragedy of being out of touch with contemporary culture and out of touch with historic Christianity. In other words, liberal mainline denominations have become sidelined denominations — relegated to the fringe of society unmoored from their past and facing a very uncertain future.

The Coming Evangelical Crisis

Despite the recent rash of books predicting a bright future for Evangelicalism, a dark future lies ahead. Evangelicalism faces the triple threat of pluralism, relativism, and subjectivism.

Pluralism can be seen in the emergence of post-denominational Christianity. Post-denominationalism has brought about a blurring of confessional identity, cafeteria style Christianity, and frequent church hopping. Ironically, post-denominationalism can be attributed to Fundamentalism (see Carpenter 1997:240). When the Fundamentalists were forced out of the mainline denominations, they responded by forming rival denominations and parachurch agencies. Many Evangelicals became acclimated to organizational pluralism after being forced to leave a liberal denomination or through participation in several parachurch ministries. The vitality of parachurch ministries was such that the local church seemed stodgy and ineffective in comparison leading to a weakening of loyalty to the local church (#23).

Relativism was an unintended consequence of Evangelicalism’s growing pluralism. The proliferation of counter-denominations and parachurch groups weakened denominational loyalties to the point where denominational distinctives became irrelevant for many. Being task-oriented and interdenominational parachurch organizations tended to frame their doctrines broadly. This resulted in a minimalist approach to core doctrines, blurring of denominational differences, and the avoidance of any discussion about ecclesiology: sacraments, liturgy, creeds, and polity (#24). In No Place for Truth, David Wells laments what he calls the “disappearance of theology” within Evangelicalism. Wells writes, “The anti-theological mood that now grips the evangelical world is changing its internal configuration, its effectiveness, and its relation to the past” (1993:96). This anti-theological mood can be seen in the following anecdote:

…I heard of a modern pastor who visited a neighboring pastor, and in the course of their conversation, he bemoaned the shameful divisions that exist within Christendom. The neighboring pastor replied that such had not always been the case. ….. He proceeded to suggest that the pastors of the area get together and address the critical issues that divided them.

“Oh!” said his visitor. “It would not be good to discuss doctrine among ourselves. Doctrine divides! We need to stay away from controversy and just get to know each other through prayer.” (Hardenbrook 1996:1978).

Although many Evangelical will deny the charges of theological relativism, many find it hard to articulate the essential core doctrines of Christianity or the Protestant Reformation.

Subjectivism is a third threat facing Evangelicalism. Evangelicalism’s drift into relativism and subjectivism has been facilitated by the whole scale abandonment of confessional standards. Or as sociologist Peter Berger put it more vividly, under the shock of pietism Protestantism underwent a meltdown of its dogmatic structures (1967:157). What matters is not so much what you believe but whether you had a “born again” experience. It was also abetted by a spiritual pragmatism found in attitudes like: “What helps you grow spiritually” or “Go where you feel God is leading you” or “I have a peace in my heart about this.” Among charismatic preachers it is quite common to hear them say: “The Lord spoke to me….” or “The Holy Spirit laid it on my heart to….” Faith has shifted away from doctrine to subjective experiences.

Evangelicalism, unlike Liberalism, can be expected to enjoy numerical growth in the near future. This is because, unlike Liberalism, Evangelicalism is more in tune with popular culture. However, that may prove to be a hollow victory. For by that time Evangelicalism may have mutated to the point where it will bear little resemblance to its Protestant roots. This is a warning given by George Barna, Evangelicalism’s leading pollster. In The Second Coming of the Church, he writes:

Evangelism will suffer in the first decade of the new millennium as Christians shrink from the aggressive questioning of the nonbelieving public. Without a visible witness to the contrary, the mass media will continue to portray churches and Christianity negatively, while giving positive affirmation to the new strains of religions and religious leaders competing for America’s souls. Christian doctrine will be sliced and diced beyond recognition–and few will know, even fewer will care (1998:208, emphasis added).

Barna’s alarm at Evangelicalism’s plight is shared by John Armstrong who edited The Coming Evangelical Crisis (1996) which describes the faultlines fracturing Evangelicalism in the 1990s: doctrine (e.g., biblical inerrancy, process theology, annihlationism), methodology (e.g., postmodern approaches to knowledge), worship (e.g., seeker friendly services), eschatology (progressive dispensationalism), ethics (e.g., homosexuality, abortion, divorce), and ministry (women’s ordination). These findings confirm the warning given by James Davidson Hunter in his Evangelicalism: The Coming Generation. Hunter’s survey research in the 1980s showed significant opinion shifts already well underway among Evangelicalism’s upcoming generation. Hunter talks of the “loss of binding address” among Evangelicals (1987:210 ff.) which is a very apt way of describing Evangelicalism’s dire straits.

In conclusion, Evangelicalism’s threefold crisis of pluralism, relativism, and subjectivism is not due to an unfortunate accident of history but is deeply rooted in Protestantism. The damning indictment for Evangelicals is that they are just as modern and syncretistic as the Liberals. This is the warning given by Peter Toon in The End of Liberal Theology: “American Evangelicals have tended to be blind to the effects and dangers of modernity because their own identity is actually tied to modernity” (1995:211 ff.). The recent Evangelical crisis shows the powerful cultural forces of post-modernity pulling the Evangelical strand of the Protestant genetic code in all directions rendering it theologically incoherent.

The Crisis of Sola Scriptura

Sola scriptura won’t work because it can’t work. It can’t work because Scripture was never intended to be understood by itself but in the context of Holy Tradition. Furthermore, sola scriptura can’t work because it is not biblical — nowhere does the Bible teach sola scriptura. Furthermore, church history shows that sola scriptura hasn’t worked in practice. The historical consequence of sola scriptura has been Protestant denominations numbering in the hundreds and thousands. Another historical consequence of sola scriptura has been the bewildering array of doctrines on just about any topic. Protestantism’s hermeneutical chaos has rendered it theologically incoherent. This incoherence has made Protestantism unable to present a unified witness to the world. Thus, sola scriptura, rather than being the foundation for Protestantism, is actually its fatal genetic flaw that results in innumerable doctrinal and ecclesiastical mutations.

In recent years sola scriptura has become the source of a major theological crisis for Protestants. Alister McGrath provides an apt description of the conundrum embedded within sola scriptura:

If the intellectual origins of the Reformation are to be explained in terms of the return to scripture as the source of Christian theology, the considerable divergence within the movement over the question of hermeneutics raises serious questions concerning the viability of this approach (1987:172).

McGrath remains a Protestant but many have grappled with sola scriptura with devastating consequences. Scott Hahn, a graduate of Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary and a Presbyterian seminary professor, was dumbfounded when a student asked him: “Professor, where does the Bible teach that ‘Scripture alone’ is our sole authority?” This question eventually led him to Roman Catholicism (Hahn 1993:51). It is only recently that Evangelicalism has begun to address this crisis. Keith Mathison’s The Shape of Sola Scriptura (2001) marks a serious attempt by a Protestant to address this problem. (See my review of Mathison’s book here.)

The tragedy of Protestantism’s hermeneutical chaos has been further compounded by the widespread tendency to ahistoricism. Modernism’s belief in progress has resulted in a kind of chronological arrogance — the attitude that the modern present is superior to the primitive backward past. Respect for the Church Fathers and the Ecumenical Councils is practically nonexistent among Protestants, whether Evangelical or Liberal. Indifference to church history has had a terrible effect on Evangelicals and Liberals alike. It has resulted in their obliviousness to how far they have drifted from the historic Christian faith. The loss of historical memory among Protestants is analogous to a person suffering from Alzheimer’s disease or attention deficit disorder. This has resulted in groups, even whole denominations, embracing bizarre doctrines, or committing themselves uncritically to the latest fads with dire consequences to their theological integrity.

The Impossibility of Evangelical Renewal

The crisis surrounding sola scriptura has serious implications for Evangelical renewal movements. The goal of these renewal movements is to help mainline denominations move away from the precipice of theological Liberalism back to the historic center (see Hamilton and McKinney 2003). But if Evangelicalism is collapsing into heterodoxy at the same time we are trying to move the mainline denomination back to the doctrinal center then something is seriously wrong. If sola scriptura is fundamentally flawed then Evangelical renewal groups are chasing an impossible dream.

I was a member of the Biblical Witness Fellowship (BWF), an evangelical renewal group in the United Church of Christ (UCC). The more I wrestled with questions about the fundamental premises of the Protestant Reformation, the more I had questions about the prospect of Evangelical renewal in the UCC. The crisis of sola scriptura became apparent to me in the Dubuque Declaration. The Dubuque Declaration — BWF’s theological charter — is a fine statement crafted by one of Evangelicalism’s leading theologians, Donald Bloesch. I had no quarrel with it theologically, but what was the basis for its authority? Why should we privilege the Dubuque Declaration over the UCC’s 1957 Basis of Union? or the Heidelberg Catechism? or the Westminster Confession? or the Cambridge Platform? The Dubuque Declaration like any other confessional statements is an interpretation of the Bible. Without establishing the proper basis for the authority for a particular confession, we are forced into a kind of arbitrary subjectivism. Why were we in the BWF reinventing the wheel, when we could be using the classic confessions of the Protestant Reformation?

Another question had to do with the ultimate goal of Evangelical renewal in the UCC. I was stumped because as a church history major I knew of numerous possibilities. Were we aiming for the UCC in the late 1950s when the historic merger took place? the Evangelical and Reformed tradition of the 1800s? the Mercersburg Movement in the 1860s? Congregationalism in the 1700s? or Calvin’s Geneva? These are not two separate questions but represent two sides of the same coin. Sola scriptura has produced in Protestantism hermeneutical chaos as well as organizational chaos. And in this situation the Reformation’s goal ecclesia reformata sed semper reformanda broke down under the weight of sola scriptura.

My Protestant Theology Falls Apart

Much of the collapse of my Protestant theology stemmed from my social location as a theologically conservative Evangelical in the liberal United Church of Christ. I found myself being confronted by theological pluralism from the left as well as from the right. On the one hand I found myself part of Evangelicalism which affirmed the authority of Scripture and yet allowed denominational diversity to flourish, and on the other hand I found myself belonging to a liberal denomination that denied the authority of Scripture and encouraged theological diversity to the point of tolerating outright heresy. The tragedy of the UCC is that it is the oldest Reformed body in America having roots in Puritan New England. I found myself in a quandary when it came to asserting the biblical faith in the face of rampant theological Liberalism. My solution to this dilemma was to combine biblical studies with church history — I argued that the biblical Evangelical position was the same as the historic Christian faith. However, this backfired when my studies as a church history major led me to the discovery that much of Evangelicalism is based upon recent innovations dating back to the 1800s.

Frustrated and disillusioned by Protestantism’s hermeneutical chaos, I became attracted to the early Church. In my research I was struck by the theological unity shared by all Christians in the first millennium. Irenaeus of Lyons, a second century bishop, wrote:

Having received this preaching and this faith, as I have said, the Church, although scattered in the whole world, carefully preserves it, as if living in one house. She believes these things [everywhere] alike, as if she had but one heart and one soul, and preaches them harmoniously, teaches them, and hands them down, as if she had but one mouth (Richardson 1970:360).

The fact that Irenaeus could assert that in his time the Church, from one end of the Roman Empire to the other, held a common faith, stood in stark contrast to modern day Protestantism where a dozen rival denominations could easily be found in the same neighborhood. Moreover, the unity of the Church in the first thousand years stands against the divisions and denominations produced by Protestants in just a few centuries time. As I continued to read Irenaeus, I became even more disturbed. Irenaeus argues that the truthfulness of the Christian faith is validated by its catholicity, i.e., its universality. He writes,

But as I said before, the real Church has one and the same faith everywhere in the world (Richardson 1970:362; emphasis added).

For Irenaeus the unity of the Church and the veracity of the Christian Faith are integral to each other; the two cannot be separated. As a Protestant Evangelical accustomed to denominational differences, I found this statement to be a shocker. It is shocking because I came to realize that the question is not: “Do I believe in the right doctrine? (which is a Protestant question)” but: “Do I belong to the true Church?” Applying Irenaeus’ theological framework meant that if I did not belong to the true Church then I was a member of a schismatic or worse a heretical body.

Finding Save Haven

Becoming Orthodox was like finding a safe haven after a long difficult journey through stormy seas. Being an Evangelical in the UCC was at times a lonely and alienating experience. I could never be sure when I met a UCC minister for the first time if we shared the same beliefs. It was only after asking a few discreet questions that I could determine whether we were on the same side of the fence or opponents. After a while it takes a toll on one’s spirit to be constantly keeping up one’s guard or phrasing one’s beliefs carefully in order to avoid conflict. It was also upsetting to be told to my face by Liberals that it would be better for me to leave the UCC. (I have also met denominational leaders who were open and accepting of Evangelicals, who worked to maintain unity between the Liberals and Evangelicals.) Just as upsetting was finding out about recent decisions made at the national UCC Synods, or the local Aha Pae’ainas or Aha Mokupunis that contradicted the teachings of Scripture (#25).

When I became Orthodox, I found it comforting to know that I shared the same faith with my priest or any other priest or bishop that I would meet. What I found in Orthodoxy — to use that delightful phrase by Bellah et al. — was a “community of memory.” It is a community that ties us to the past and turns us towards the future through its “practices of commitment” (1985:152 ff.). Orthodoxy throughout the world is bound together by a common Liturgy, the Nicene Creed, and the Seven Ecumenical Councils. Moreover, I found the doctrine and worship of the Orthodox Church to be saturated with Scripture references. Because Orthodoxy sees Scripture as an integral part of Holy Tradition, it is far more able to safeguard Scripture than Protestantism with its sola scriptura. Like the telomeres that safeguard the integrity of DNA, so Holy Tradition safeguards Scripture from false readings and ensures doctrinal unity.

My attraction to Orthodoxy is more than an interest in antiquarianism and rituals. Rather, it lies in the quest for the true faith. Orthodoxy, being grounded in the eternal truths of the Kingdom of God, will endure and outlast the challenge of a post-modern and post-Christian culture. In Facing East Frederica Matthewes-Green describes her first visit to an Orthodox service:

The truth part was this: the ancient words of this vesperal service had been chanted for more than a millennium. Lex orandi, lex credendi; what people pray shapes what they believe. This was a church that had never, could never, apostatize (1997:xiii).

Robert Arakaki

REFERENCES

Ahlstrom, Sydney E. 1975. A Religious History of the American People. Volume 2. Garden City, New York: Image Books.

Armstrong, John H., ed. 1996. The Coming Evangelical Crisis. Chicago: Moody Press.

Barna, George. 1998. The Second Coming of the Church. Nashville: Word Publishing.

Bellah, Robert N. and Richard Madsen, William M. Sullivan, Ann Swidler, and Steven M. Tipton. 1985. Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life. New York: Harper and Row, Publishers.

Berger, Peter L. 1979. The Heretical Imperative: Contemporary Possibilities of Religious Affirmation. Garden City, New York: Anchor Press/Doubleday.

Berger, Peter L. 1967. The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion. New York: Anchor Books.

Berger, Peter L. and Thomas Luckmann. 1967. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. Garden City, New York: Doubleday and Company, Inc.

Board, Stephen. 1979. “The Great Evangelical Power Shift: How has the mushrooming of parachurch organizations changed the church?” Eternity (June), pp. 17-21.

Carpenter, Joel A. 1997. Revive Us Again: The Reawakening of American Fundamentalism. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cherry, Conrad. 1995. Hurrying Toward Zion: Universities, Divinity Schools, and American Protestantism. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Gorman, Christine. 1998. “An Attack on Aging.” Times (January 28), p. 60.

Hadden, Jeffrey K. 1969. The Gathering Storm in the Churches: The Widening Gap Between Clergy and Laymen. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc.

Hahn, Scott and Kimberly Hahn. 1993. Rome Sweet Home: Our Journey to Catholicism. San Francisco: Ignatius Press.

Hamilton, Michael S. 1997. “The Dissatisfaction of Francis Schaeffer, Part I” Christianity Today Vol. 41 No. 3 (March 3), page 22.

Hamilton, Michael S. and Jennifer McKinney. 2003. “Turning the Mainline Around” Christianity Today (August): pp. 34-40.

Hardenbrook, Weldon (with Terry Somerville). 1996. Missing From Action. Ben Lomond, California: Conciliar Press.

Hatch, Nathan O. 1982. “Sola Scriptura and Novus Ordo Seclorum” in The Bible in America: Essays in Cultural History, pp. 59-78. Nathan O. Hatch and Mark A. Noll, eds. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Horton, Michael S. 1996. “Recovering the Plumb Line” in The Coming Evangelical Crisis, pp. 245-265. John H. Armstrong, ed. Chicago: Moody Press.

Hughes, Richard T. ed. 1995. The Primitive Church in the Modern World. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Hunter, James Davidson. 1987. Evangelicalism: The Coming Generation. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Hutcheson, Richard. 1981. Mainline churches and the evangelicals: a challenging crisis? Atlanta, Georgia: John Knox Press.

Hutchison, William R. 1976. The Modernist Impulse in American Protestantism. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Latourette, Kenneth Scott. 1953. A History of Christianity. Volume II: A.D. 1500–A.D. 1975. (Expanded edition 1975 with chapter 62 by Ralph D. Winter) San Francisco: Harper & Row Publishers.

Lewis, Bernard. 1982. The Muslim Discovery of Europe. New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company.

Marsden, George M. 1987. Reforming Fundamentalism: Fuller Seminary and the New Evangelicalism. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Mathison, Keith. 2001. The Shape of Sola Scriptura. Moscow, Idaho: Canon Press.

Matthewes-Green, Frederica. 1997. Facing East: A Pilgrim’s Journey Into The Mysteries of Orthodoxy. New York: HarperCollins.

Maudlin, Michael. 1998. “Inside CT: How Can a False Religion Be So Successful?” Christianity Today (June 15), p. 5.

McGrath, Alister. 1987. The Intellectual Origins of the European Reformation. Oxford, England and Cambridge, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishers, Ltd.

Moore, R. Laurence. 1994. Selling God: American Religion in the Marketplace of Culture. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Noll, Mark A. 1994. The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Noll, Mark A. 1991. Between Faith and Criticism: Evangelicals, Scholarship, and the Bible in America. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House.

Noll, Mark A. 1985. “Commonsense Traditions in American Evangelical Thought” American Quarterly Vol. 37 No. 2 (Summer), pp. 216-237.

Oden, Thomas C. 1994. “Confessions of a Grieving Seminary Professor” Good News magazine (January/February).

Oden, Thomas C. 1990. After Modernity …. What?: Agenda for Theology. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan Publishing House.

Osterhaven, M.M. 1984. “Rule of Faith” in Evangelical Dictionary of Theology, pp. 961-962. Walter A. Elwell, ed. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House.

Pelikan, Jaroslav. 1971. The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600). The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine. Volume I. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Quebedeaux, Richard. 1980. The Worldly Evangelicals. San Francisco: Harper & Row, Publishers.

Quebedeaux, Richard. 1974. The Young Evangelicals: Revolution in Orthodoxy. San Francisco: Harper & Row, Publishers.

Ramm, Bernard. 1970. Protestant Biblical Interpretation: A Textbook of Hermeneutics. Third revised edition. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House.

Richardson, Cyril C., ed. 1970. Early Christian Fathers. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc.

Roof, Wade Clark. 1999. Spiritual Marketplace: Baby Boomers and the Remaking of American Religion. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Rosenau, Pauline Marie. 1992. Post-Modernism and the Social Sciences: Insights, Inroads, and Intrusions. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Tambiah, Stanley Jeyaraja. 1990. Magic, science, religion, and the scope of rationality. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Taylor, LaTonya. 2002. “The Church of O” Christianity Today (April 1).

Toon, Peter. 1995. The End of Liberal Theology: Contemporary Challenges to Evangelical Orthodoxy. Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway Books.

Watson, James D. 1968. The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA. New York: Mentor Books, 1968.

Wells, David F. 1993. No Place for Truth or Whatever Happened to Evangelical Theology? Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Wells, David F. 1994. God In The Wasteland: The Reality of Truth in a World of Fading Dreams. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Wuthnow, Robert. 1988. The Restructuring of American Religion: Society and Faith Since World War II. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

NOTES

I would like to thank Dr. Michael Bressem for his careful reading and constructive criticism of my earlier draft.

(#1) The expression regula fidei “rule of faith” was first used towards the end of the second century. Two of the earliest advocates of this method were Irenaeus of Lyons and Tertullian.

(#2) It should be noted that the Protestant Reformers were rejecting the traditions of medieval Catholicism, not the Holy Tradition of the early Church. For example, medieval Catholicism introduced theological innovations such as the supreme authority of the Papacy, purgatory, and the Filioque which has never been part of the historic Christian Faith and which Orthodoxy rejects.

(#3) Basically, this was the principle that if the ruler was Protestant, the religion of the land would be Protestant and visa versa.

(#4) See The Primitive Church in the Modern World (Richard T. Hughes, ed., 1995) for an account of how the dream of restoring primitive Christianity played a powerful role in American Protestantism. The book also provides an insightful discussion of how the restorationist impulse is a response to modernity.

(#5) See Nathan Hatch’s “Sola Scriptura and Novus Ordo Seculorum” for an analysis of how sola scriptura took on new meanings as it was interpreted through the lenses of democracy and individualism.

(#6) This is the argument made in R. Laurence Moore’s Selling God (1994:7). Moore notes that sola fide if pushed to the extreme made churches and ministers unnecessary and for that reason Protestant countries in Europe made church attendance mandatory (1994:14).

(#7) It is interesting to note that the same millennial impulse also gave rise to the Jehovah Witnesses and the Seventh Day Adventists. this makes Evangelicalism part of the same sociological family as the Jehovah Witnesses, Seventh Day Adventists, the Mormons (Latter Day Saints) and other nineteenth century sects. This uncanny family resemblance can be seen in a Christianity Today editor’s account of his visit to his Mormon relatives (see Maudlin 1998).

(#8) The Holiness Movement stressed the need for two distinct work of grace in the Christian’s life. The first being the initial conversion experience where one receives justification and the second being the “second blessing” in which one becomes totally sanctified. It should be noted that this emphasis on two pivotal experiences in the Christian life is alien to the Eastern Orthodox and to classical spirituality.

(#9) David Wells has made a similar argument in his God In The Wasteland (1994:174).

(#10) A similar observation has been made by Conrad Cherry who sees the Modernist/Fundamentalist conflict as a clash between elite and folk cultures (Cherry 1995:173).

(#11) Protestantism is inseparable from modernity. It was Protestantism that gave rise to modernity in the West (see Stanley Tambiah’s Magic, science, religion, and the scope of rationality 1990:12 ff.). Bernard Lewis attributes the freeing of thought from ecclesiastical authority by the Reformation as one of the causes for the intellectual explosion in Europe (1982:301).

(#12) Latourette notes that although not primarily a theologian, Hegel had a powerful influence on theologians (1953:1125).

(#13) Strauss held that post for a short time until clerical opposition resulted in his ouster. Subsequent to that he became a free lance writer.

(#14) At the outset a professor of theology, Wellhausesn later devoted himself to the study of oriental languages at the same university.

(#15) Mark Noll describes the influence of the Scottish Commonsense philosophy on American Evangelicalism in his article “Commonsense Tradition and American Evangelical Theology” (1985).

(#16) Fundamentalism’s rejection of modern science is not as simple as it appears. See Mark Noll’s chapter “The Evangelical Love Affair with Enlightenment Science” (Noll 1991:122 ff.).

(#17) See Mark Noll’s chapter “The Rise of Fundamentalism, 1870-1930” for a description of the events and trends that led to the Liberal/Fundamentalist confrontation (1991:9 ff.).

(#18) Michael Hamilton notes that in the 1960s Francis Schaeffer electrified Evangelical students with his willingness to talk about contemporary film makers like Berman and Fellini at a time when Wheaton College banned the popular movie “Bambi” from the school campus.

(#19) In his Mainline churches and the evangelicals Richard Hutcheson gives an amusing anecdote of a gathering of high level denomination officials talking shop while their children were attending a local Youth For Christ rally.

(#20) The suffix -ism indicates post-modernism as an ideological stance, as opposed to post-modernity which refers to a particular social situation. For a good overview of post-modernism, see Pauline Rosenau’s Post-Modernism and the Social Sciences (1992).

(#21) Wade Clark Roof refers to the emergence of a “quest culture” among Baby Boomers in his Spiritual Marketplace (1999).

(#22) Conrad Cherry recounts how strong tensions resulted when Yale Divinity School faculty were denied positions on the graduate faculty of the newly formed Department of Religious Studies, and students in the new department were no longer required to register in the Divinity School (1995:121).

(#23) See Stephen Board’s article “The Great Evangelical Power Shift: How has the mushrooming of parachurch organizations changed the church?” (1979).

(#24) This can be seen in the widespread practice of open communion among Protestants. Open communion — allowing Christians from other denominations to take communion — is a very recent practice dating back to the 1960s! (See Wuthnow 1988:92)

(#25) In the Hawaii Conference of the United Church of Christ the annual statewide gathering of UCC churches is known as the Aha Paeaina and the biannual gatherings of island associations are known as the Aha Mokupuni. The UCC is the oldest and largest Protestant denomination in Hawaii. The Congregationalist missionaries brought the Good News of Christ to the Hawaiian Islands in the early 1800s.

The Great Library of Alexandria (established during the reign of Pharaoh Ptolemy II Philadelphus, ca. 283-246 BC, and originally organized by a student of Aristotle) contained innumerable manuscripts, works and scrolls from all over the world.

The Great Library of Alexandria (established during the reign of Pharaoh Ptolemy II Philadelphus, ca. 283-246 BC, and originally organized by a student of Aristotle) contained innumerable manuscripts, works and scrolls from all over the world. And so, when we read the Gospel account of Christ being brought to the Temple as an infant, the elder Simeon is still there after 200 years, waiting to see the Messiah of Israel with his own eyes, just as the angel had promised him. Simeon immediately recognizes that Jesus is in fact the Christ (the Messiah) of Israel, and responds appropriately: “Lord, now let Your servant depart in peace, according to Your word, for my eyes have seen Your salvation, a Light to lighten the Gentiles and the Glory of Your people Israel” (Gospel Acc. to Luke 2:25-32). This passage, the Song of Simeon, is known in the West as the nunc dimittis, meaning “now dismiss” from its appearance in the Latin Vulgate.

And so, when we read the Gospel account of Christ being brought to the Temple as an infant, the elder Simeon is still there after 200 years, waiting to see the Messiah of Israel with his own eyes, just as the angel had promised him. Simeon immediately recognizes that Jesus is in fact the Christ (the Messiah) of Israel, and responds appropriately: “Lord, now let Your servant depart in peace, according to Your word, for my eyes have seen Your salvation, a Light to lighten the Gentiles and the Glory of Your people Israel” (Gospel Acc. to Luke 2:25-32). This passage, the Song of Simeon, is known in the West as the nunc dimittis, meaning “now dismiss” from its appearance in the Latin Vulgate.

Recent Comments