In a 30 December 2012 canonwired podcast, Pastor Doug Wilson was asked what he thought about Protestants crossing themselves. Apparently, this question was asked because growing numbers of Protestants have started crossing themselves. In short, Pastor Wilson’s answer was: “It’s lawful, but it’s not appropriate at all.”

In a 30 December 2012 canonwired podcast, Pastor Doug Wilson was asked what he thought about Protestants crossing themselves. Apparently, this question was asked because growing numbers of Protestants have started crossing themselves. In short, Pastor Wilson’s answer was: “It’s lawful, but it’s not appropriate at all.”

He elaborated that it would not be appropriate because it could cause confusion, that is, a Protestant making the sign of the cross might be mistaken for a Roman Catholic.

In this blog posting I will be discussing: (1) the origins of this practice, (2) why many Protestants do not cross themselves, (3) what this gesture means for Orthodox Christians, and (4) the significance of the recent interest among Protestants in this ancient Christian practice.

Fourth century icon of St. Paul

In the Early Church

The origin of the sign of the cross is unknown. It was probably first made on the forehead of those being baptized. It appears that people began to cross themselves during the early liturgies then carried the practice over into everyday life. In time this practice became emblematic of being a Christian. Based on early descriptions we can infer that the gesture was first made with one finger tracing a T or an X on the forehead. Possibly, the early Christians took their cue from Genesis 4:15, Ezekiel 9:4, and Revelation 14:1 and 22:4. Then the gesture took on more elaborate forms with two fingers used to indicate the two natures of Christ or three fingers to indicate faith in the Trinity.

While the origin of the sign of the cross is obscure, it is evident that the early Christians saw it as an integral part of an ancient tradition. The second century apologist, Tertullian (c. 160/170-215/220), defended Holy Tradition by pointing to the sign of the cross as an example of an ancient custom all Christians shared in. Tertullian wrote:

And how long shall we draw the saw to and fro through this line, when we have an ancient practice, which by anticipation has made for us the state, i.e., of the question? If no passage of Scripture has prescribed it, assuredly custom, which without doubt flowed from tradition, has confirmed it. For how can anything come into use, if it has not first been handed down? . . . . At every forward step and movement, at every going in and out, when we put on our clothes and shoes, when we bathe, when we sit at table, when we light the lamps, on couch, on seat, in all the ordinary actions of daily life, we trace upon the forehead the sign. (De Corona Chapter 3)

If the sign of the cross was considered an ancient practice in Tertullian’s time circa 200, we can infer that it was in use in the first half of the second century and possibly as early as the start of the second century soon after the Apostles died.

Similarly, Basil the Great (c. 329-379) pointed to the sign of the cross as a prime example of unwritten tradition. In his On the Holy Spirit Basil wrote:

Of the beliefs and practices whether generally accepted or publicly enjoined which are preserved in the Church some we possess derived from written teaching; others we have received delivered to us “in a mystery” by the tradition of the apostles; and both of these in relation to true religion have the same force. And these no one will gainsay—no one, at all events, who is even moderately versed in the institutions of the Church. For were we to attempt to reject such customs as have no written authority, on the ground that the importance they possess is small, we should unintentionally injure the Gospel in its very vitals; or, rather, should make our public definition a mere phrase and nothing more. For instance, to take the first and most general example, who is thence who has taught us in writing to sign with the sign of the cross those who have trusted in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ? (On the Holy Spirit Chapter 27, §66)

Basil asserted that to omit an established custom on the grounds that it lacks biblical backing or it is trivial would “injure the Gospel in its very vitals.”

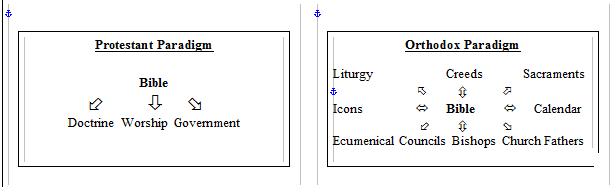

In their defense of the sign of the cross Tertullian and Basil the Great anticipated and refuted the regulative principle, i.e., what the Bible does not teach is not to be allowed. The regulative principle being foundational to Reformed hermeneutics points to a fundamental incompatibility between the Reformed tradition and early Christianity. While theologically astute Protestants might point out that the classic form of sola scriptura allows for extra-biblical traditions, a Protestant would not be able to agree with Basil’s assertion that unwritten tradition “have the same force” as Scripture which is how Orthodoxy views the relation between Scripture and Tradition.

Readers who are skeptical of Holy Tradition should keep in mind that Tradition like Scripture did not fall out of the sky but is rooted in the ministry of the original Apostles. In an earlier blog: “The Biblical Basis for Holy Tradition” I examined what the New Testament had to say about the process of handing down oral and written apostolic tradition. In my critique of Keith Mathison’s Shape of Sola Scriptura I argued that the early church fathers did not hold to sola scriptura but to both Scripture and Tradition.

In Everyday Christian Life

The significance of the sign of the cross can be seen in its widespread usage among the early Christians. Tertullian described how early Christians carried this practice into their ordinary day-to-day activities in an attempt to consecrate all aspects of their new life in Christ.

At every forward step and movement, at every going in and out, when we put on our clothes and shoes, when we bathe, when we sit at table, when we light the lamps, on couch, on seat, in all the ordinary actions of daily life, we trace upon the forehead the sign. (De Corona Chapter 3)

Two centuries later, Cyril (c. 310-386), Patriarch of Jerusalem, exhorted the catechumens to incorporate the sign of the cross into the fabric of everyday life. In Lecture 4 of his Catechetical Lectures Cyril exhorted his listeners not to be ashamed concealing their faith in Christ but to be bold witnesses for Christ by signing themselves with the cross openly and publicly.

Let us, therefore, not be ashamed of the Cross of Christ; but though another hide it, do thou openly seal it upon thy forehead, that the devils may behold the royal sign and flee trembling far away. Make then this sign at eating and drinking, at sitting, at lying down, at rising up, at speaking, at walking: in a word, at every act. For He who was here crucified is in heaven above. If after being crucified and buried He had remained in the tomb, we should have had cause to be ashamed; but, in fact, He who was crucified on Golgotha here, has ascended into heaven from the Mount of Olives on the East. (NPNF Vol. 7 p. 22)

The phrase “royal sign” points to the sign of the cross as a flag signaling the presence of the kingdom of God. Christ’s reign requires a visible sign. In World War II, when the Allies retook a town they would take down the Nazi flag and raise the flag of the original state. In Lecture 13 Cyril reiterated how the sign of the cross was to be woven into the everyday fabric of life.

Let us not then be ashamed to confess the Crucified. Be the Cross our seal made with boldness by our fingers on our brow, and on everything; over the bread we eat, and the cups we drink; in our comings in, and goings out; before our sleep, when we lie down and when we rise up; when we are in the way, and when we are still. Great is that preservative; it is without price, for the sake of the poor; without toil, for the sick; since also its grace is from God. It is the Sign of the faithful, and the dread of devils: for He triumphed over them in it, having made a shew of them openly; for when they see the Cross they are reminded of the Crucified; they are afraid of Him, who bruised the heads of the dragon. Despise not the Seal, because of the freeness of the gift; out for this the rather honour thy Benefactor. (NPNF Vol. 7 p. 92)

The phrase “on everything” points to the priesthood of all believers (cf. I Peter 2:9). Just as the Christian clergy consecrated the Eucharistic elements so likewise the Christian laity consecrated their ordinary meals and turned their mundane secular activities into sacred moments that became an extension of the kingdom of God. This fulfills Paul’s cosmic vision in Ephesians of all creation being united under Christ’s rule (Ephesians 1:19-23).

Faith In Motion

The sign of the cross is more than a ritual gesture made with the fingers, it is faith in action. John Chrysostom noted that genuine faith is needed for this gesture to be efficacious:

Since not merely by the fingers ought one to engrave it, but before this by the purpose of the heart with much faith. (Gospel of St. Matthew, Homily 54, NPNF Vol. 10 p. 336)

In making the sign of the cross we affirm visibly and bodily our faith in the Trinity, and we confess the Good News of Christ’s death and his third day resurrection. St. John also exhorts his listeners to sanctify their minds and their souls through the sign of the cross.

This therefore do thou engrave upon your mind, and embrace the salvation of our souls. For this cross saved and converted the world, drove away error, brought back truth, made earth Heaven, fashioned men into angels. Because of this, the devils are no longer terrible, but contemptible; neither is death, death, but a sleep; because of this, all that wars against us is cast to the ground, and trodden under foot. (Gospel of St. Matthew, Homily 54, NPNF Vol. 10 p. 336)

The sign of the cross also promotes our spiritual wellbeing. For example, being insulted can become a stumbling block but making the sign of the cross can help us maintain our spiritual balance.

Hath any one insulted thee? Place the sign upon thy breast, call to mind all the things that were then done; and all is quenched. Consider not the insults only, but if also any good hath been ever done unto thee, by him that hath insulted thee, and straightway thou wilt become meek, or rather consider before all things the fear of God, and soon thou wilt be mild and gentle. (Gospel of St. Matthew, Homily 87, NPNF Vol. 10 p. 518)

Oftentimes when Orthodox Christians encounter a trial or a temptation they will cross themselves and pray: Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me a sinner!

Making the sign of the cross provides the sincere Christian an added boost to his/her prayer. Our bodily actions affect our souls. All too often one feels like one is thinking to one’s self than talking to God but a bodily gesture like kneeling or crossing one’s self changes all that. I suspect that the Puritan attempt to reduce prayer to its bare minimum might have roots in the sola fide. “Faith alone” can be turned into an abstract intellectual faith without good works, and a faith without outward gestures like the sign of the cross or bowing one’s head in worship.

Christus Victor

In the early Church the dominant motif of salvation was Christus Victor – Christ as the one who defeated death and the Devil on our behalf. For the early Christians the sign of the cross was an act of spiritual force. Athanasius the Great (c. 296-373) in his De Incarnatione Verbi Dei discussed how Christians use the sign of the cross as a way of repudiating death.

A very strong proof of this destruction of death and its conquest by the cross is supplied by a present fact, namely this. All the disciples of Christ despise death; they take the offensive against it and, instead of fearing it, by the sign of the cross and by faith in Christ trample on it as on something dead. (De Incarnatione § 27)

The early Christians believed the sign of the cross was a spiritual force that defeated the influence of paganism and idolatry. As an act of faith this sacramental gesture announces that the kingdom of God has come and presents the call to repentance, i.e., to return God the true Creator of humanity and creation. The kingdom of God which has been obscured by the Fall is now made manifest. Or to use the words of the late Protestant missiologist Ralph Winter: “the kingdom strikes back.”

By the sign of the cross, on the contrary, all magic is stayed, all sorcery confounded, all the idols are abandoned and deserted, and all senseless pleasure ceases, as the eye of faith looks up from earth to heaven. (De Incarnatione § 31)

Athanasius linked the sign of the cross with the missionizing of Roman society. Paganism was being overthrown not just by verbal proclamation of the Gospel but also by the manifestation of Christ’s kingdom through the sign of the cross.

Since the Savior came to dwell among us, not only does idolatry no longer increase, but it is getting less and gradually ceasing to be. Similarly, not only does the wisdom of the Greeks no longer make any progress, but that which used to be is disappearing. And demons, so far from continuing to impose on people by their deceits and oracle-givings and sorceries, are routed by the sign of the cross if they so much as try. (De Incarnatione § 55)

Thus, what may look like a quaint church ritual is actually an ancient spiritual practice of considerable potency. With this simple gesture we proclaim the coming of the kingdom of God, the defeat of death, and the renewal of creation.

Summary: While the origin of the sign of the cross is obscure, early Christians regarded it as an integral part of the Christian Holy Tradition. They regarded it as more than a ceremonial gesture used in church but as a vital act of faith in Christ. They saw it as a sign of Christ’s victory over sin, demons, and death, and as a means of consecrating a fallen creation thereby restoring its sacramental character prior to the Fall.

East Vs. West

While the sign of the cross was universal in the early Church, it was by no means uniform. The way Roman Catholics make the sign of the cross is different from the way Orthodox Christians make the sign of the cross. The Roman Catholic fashion is simpler. One simply touches the forehead with the right hand, move down to the chest, then touch the left shoulder and conclude by touching the right shoulder. While making this gesture, one says: “In the Name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Amen.”

Orthodox Sign of the Cross

The Eastern Orthodox style is more complex. One brings the thumb, index finger, and right hand together (symbolizing the Trinity). Then one presses the fourth and fifth fingers against the palm (symbolizing the two natures of Christ). One starts by touching the forehead, move down to the chest, then touch the right shoulder, and conclude by touching the left shoulder. While making this gesture, one says: “In the Name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Amen.”

Behind the differences in the way Roman Catholics and Orthodox make the sign of the cross today is a complex history of divergent practices, misunderstanding, even excommunication!

The Early Reformers’ Tolerance of the Sign of the Cross

Stained Glass of Martin Luther

Martin Luther’s attitude towards the sign of the cross was one of acceptance. In Luther’s Smaller Catechism we find in the section on Daily Prayers that the Christian is to make the sign of the cross before commencing the Morning and Evening Prayers.

Morning Prayer

In the morning when you get up, make the sign of the holy cross and say:

In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen. Then, kneeling or standing, repeat the Creed and the Lord’s Prayer. If you choose, you may also say this little prayer:

I thank You, my heavenly Father, through Jesus Christ, Your dear Son, that You have kept me this night from all harm and danger; and I pray that You would keep me this day also from sin and every evil, that all my doings and life may please You. For into Your hands I commend myself, my body and soul, and all things. Let Your holy angel be with me, that the evil foe may have no power over me. Amen.

Then go joyfully to your work, singing a hymn, like that of the Ten Commandments, or whatever your devotion may suggest.

The Lutheran tradition today is quite diverse, but there is a high church strand that retains and favors traditional elements like the sign of the cross, liturgical worship, and icon like stained glass windows.

John Calvin’s attitude seems to have been one of indifference or tolerance. In his Institutes the sign of the cross is mentioned in a quote by Augustine of Hippo pertaining to the sacraments of baptism and the Eucharist. In comparison with Luther, Calvin seems to hold a disdainful attitude as evidenced by his characterizing the sign of the cross as “a superstitious rite.”

Elsewhere, explaining how believers now possess Christ, he says, “You have him by the sign of the cross, by the sacrament of baptism, by the meat and drink of the altar” (Tract. in Joann. 50). How rightly he enumerates a superstitious rite, among the symbols of Christ’s presence, I dispute not; but in comparing the presence of the flesh to the sign of the cross, he sufficiently shows that he has no idea of a twofold body of Christ, one lurking concealed under the bread, and another sitting visible in heaven. If there is any need of explanation, it is immediately added, “In respect of the presence of his majesty, we have Christ always: in respect of the presence of his flesh, it is rightly said, Me ye have not always.'” (Institutes 4.17.28)

While Calvin did not openly oppose the sign of the cross, his disdainful attitude would in time develop into outright opposition by his followers.

The Reformed Opposition to the Sign of the Cross

Where Luther and his followers had an accepting attitude towards the sign of the cross and other liturgical rites, the Reformed movement had a more hostile attitude. This hostility can be found in the Scots Confession (1560) Chapter 20 in a oblique comment made about the need to change ceremonies that “foster superstition.” In the Second Helvetic Confession (1566) Chapter 27 we find a more explicit disapproval.

Therefore, we would seem to be bringing in and restoring Judaism if we were to increase ceremonies and rites in Christ’s Church according to the custom in the ancient church.

Reading between the lines we can see a rejection of rites like the sign of the cross. What is striking about the sentence above is the early Calvinists’ willingness to distance themselves from the early Church. In light of the fact that these two confessional statements were drafted just before Calvin’s passing or soon after indicates that this is not a later development but likely an expression of Calvin’s own views.

King James and Puritans at Hampton Court (1604)

The views of the Continental Reformers began to extend to England where the Anglican Via Media was in place. The Millenary Petition of 1603, signed by a thousand Puritan ministers and addressed to King James, called for a number of reforms in the Church of England. It called for the cessation of the sign of the cross being made at baptism and people bowing their heads at Jesus’ name during church services. This rejection is consistent with their adherence to the regulative principle in interpreting the Bible – what the Bible does not teach is prohibited, and with their desire to purify or rid the Church of England all “poperies” – anything reminiscent of Roman Catholicism. It is a little curious that the Westminster Confession and the Larger and Shorter Catechisms do not criticize ceremonies or rites, but the fact is the Scots Confession (1560) and the Second Helvetic Confession (1566) are considered major confessional statements for Reformed churches.

Knowing this history helps us to understand the contours of American Protestantism. Much of American Protestantism trace their roots to English Puritanism, e.g., New England Puritanism, Congregationalism, Presbyterianism, Baptist etc., and because of this the mainstream of American Protestantism do not make the sign of the cross. The Lutheran and Anglican traditions which favor or are tolerant of the sign of the cross tend to be on the sidelines of American Protestantism; the Anglicans because they were on the losing side of the Revolutionary War, and the Lutherans because their German ethnic and linguistic heritage differed from the Anglo mainstream. Many of the Protestant denominations that emerged in the 1800s, because they had very little or no knowledge of historic Christianity, tended to reflect the general Protestant attitude of not making the sign of the cross.

The Sign of the Cross in the Orthodox Tradition

Orthodox Crossing Themselves

A visitor to the Orthodox Liturgy will notice that Orthodox Christians make the sign of the cross quite frequently. They may wonder: When are Orthodox Christians expected to the make the sign of the cross? The answer can vary. The basic expectation is that one makes the sign of the cross whenever the Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are mentioned. Some Orthodox Christians will cross themselves when the Virgin Mary is mentioned. The sign of the cross can also function as a heartfelt “Amen!” to a particular prayer being offered up.

There is no hard and fast rule as to when and how often one should cross one’s self. The main thing is that the gesture be heartfelt and directed to God. I often tell visitors not to feel obligated to make the sign of the cross if they are not Orthodox. They can do it if they wish but they are not expected to do so. One could say that making the sign of the cross is a family practice. It’s something we expect of family members, not guests.

Knowing the differences between the way Orthodox, Roman Catholics, and Protestants view the sign of the cross can be helpful. I usually sit in the back of the church on Sunday mornings because that is where many visitors like to sit. When I see a visitor or a new family I usually watch to see if whether or not they cross themselves, and if they do whether it is in the Roman Catholic fashion or the Orthodox. If the sign of the Cross ends up on the right shoulder usually it’s an indicator that the person is Roman Catholic. Usually, someone not crossing themselves in the Liturgy is a tip off that they are Protestant or that they are not Christian. If they appear to be lost I offer to help them follow the Liturgy.

Should Protestants Make the Sign of the Cross?

Pastor Doug Wilson overstated his answer when he pronounced making the sign of the cross “not appropriate at all” for Protestants. While he may have the authority to speak for his congregation and his denominational group (CREC, Communion of Reformed Evangelical Churches), he has no basis to speak for all Protestants. He could claim that making the sign of the cross is inappropriate for Reformed Christians in light of the Reformed creeds.

Due to historical circumstances the vast majority of Protestants do not make the sign of the cross. I see this as a fact to be accepted, not as an error to be corrected. Protestantism has decided to walk apart from the historic churches. I recognize that a few of the more traditional or high church Protestants make the sign of the cross but they are rare exceptions. When I see someone at an Orthodox liturgy not signing themselves my first guess is that they are likely Protestant. If this individual or family were to start crossing themselves later on, I would interpret this as a sign that they are moving towards Orthodoxy.

If a Calvinist were to ask my view on their doing the sign of the cross, I would encourage them to do so. First, I would point out that the sign of the cross is not confined to any one denomination but was universal among all Christians in the early Church. Second, some of the early Protestant Reformers and some high church Protestants today (Lutherans or Anglicans) maintain this practice. Third, but because it marks a break from the Reformed movement which eschews ceremonialism and outward signs I would caution Calvinists to consider that for them to cross themselves would mark a break from the Reformed tradition. They should do it with a good conscience. And fourth, making the sign of the cross can be a first step towards becoming Orthodox. One can observe an Orthodox Liturgy as a detached observer but to cross one’s self during the Liturgy is to take the first step to active participation in the Divine Liturgy. The sign of the cross enables one to rediscover the classic Christian worldview of creation as a sacrament and the Cross as the means by which the Devil is defeated, the Fall of humanity reversed, and the cosmos redeemed.

Conclusion

The Reformed rejection of the sign of the cross is a good example of throwing out the baby with the bathwater. In their zeal to distance Protestantism from Roman Catholicism, many Reformed Christians were willing to distance themselves from the early Church as evidenced by Chapter 27 of the Second Helvetic Confession and the general attitude. The result has been the severing of Protestantism from its historic roots.

Many Protestants and Evangelicals today have become aware of this disconnect and are seeking to reconnect with their ancient Christian heritage. Some, in reaction to the disembodied cerebral approach to worship, have embraced liturgical worship and the sign of the cross. This interest, even among Reformed Christians, is probably what prompted the question to Pastor Doug Wilson. Not too long ago raising the issue of Calvinists making the sign of the cross would have caused consternation and puzzlement: Why would a Calvinist or a staunch Evangelical want to make the sign of the cross? Why even ask the question? But the landscape of Protestantism has shifted significantly in recent years. Evangelicals and Reformed Christians are now engaging in deep conversation with Roman Catholics and Orthodox Christians. These conversations are stretching the theological paradigms of many Protestants and causing some to ask questions that go beyond the usual theological parameters.

A Question For Protestants

Protestants who wish to reclaim their ancient Christian heritage by crossing themselves will need to ask themselves sooner or later how tightly they want to hold on to their Protestantism. I raise this question because as Tertullian and Basil the Great pointed out the sign of the cross is not grounded in Scripture but in Tradition. This raises the question as to whether one makes the sign of the cross for cool trendy post-modern reasons or because it is part of the ancient Christian Holy Tradition. To embrace Holy Tradition means giving serious consideration to the Orthodox Church’s claim to be the bearer of Holy Tradition.

I close with a quote from Clark Carlton on the ancient-future movement:

There is also a great difference between claiming tradition for oneself and being claimed by tradition. I, along with Webber and the contributors to his book, was perfectly willing to claim the historic Church and the liturgy for my own understanding of Christianity. Yet, I was still in control! I, in true Protestant fashion, was judge and jury of what would and would not fit into my kind of Christianity. I was willing to claim the historic Church, but I had yet to recognize Her claim on me.

Carlton, a former Southern Baptist seminarian who converted to Orthodoxy, came to this startling insight:

Gradually I came to recognize the fact that Holy Tradition has the same claim upon my life as the Gospel itself, for Tradition is nothing other than the Gospel lived throughout history.

Robert Arakaki

Recommended Reading

The late Father Peter Gillquist, an Evangelical convert to Orthodoxy, devoted one chapter of his book Becoming Orthodox, Chapter 9 – “A Sign For All Christians” to the subject of the sign of the cross.

The second half of the Liturgy, the Eucharist, is rooted in Tradition. St. Paul in I Corinthians 11:23 told the Christians in Corinth that the way he celebrated the Eucharist was based on a tradition that went back to Christ himself. The early Church had a variety of liturgies but by the fifth century the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom became the norm in much of the Greek speaking world. In the early Church the Eucharist was a normal part of the Sunday worship (see The Didache Chapter 14). This stands in contrast to the infrequent observance of the Eucharist in many Protestant churches today.

The second half of the Liturgy, the Eucharist, is rooted in Tradition. St. Paul in I Corinthians 11:23 told the Christians in Corinth that the way he celebrated the Eucharist was based on a tradition that went back to Christ himself. The early Church had a variety of liturgies but by the fifth century the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom became the norm in much of the Greek speaking world. In the early Church the Eucharist was a normal part of the Sunday worship (see The Didache Chapter 14). This stands in contrast to the infrequent observance of the Eucharist in many Protestant churches today.

Recent Comments