The “fall of the church” heresy is widely held among Protestants but not unique to Protestants. The “fall of the church” was something that early Christians had to contend with as well. Tertullian answered it in “The Prescription Against Heretics.”

The “fall of the church” refers to the belief that after the Apostles died the early Christians strayed from the original Apostles’ teachings and practices. This has been known as the great Apostasy, or the BOBO theory – the Blink Off/Blink On of the Holy Spirit’s activity in the life of the Church.

Tertullian (c. 160 – c. 225) lived in Carthage, a North African Roman province. He was a lawyer by training and one of the more influential Latin theologians in the early Church. While he did fall into error towards the end of his life and is not considered by many Orthodox a “church father,” his early writings can nevertheless be helpful to understanding early Christianity.

Prescription is one of the more important and highly regarded works of Tertullian for patristic studies. Quasten wrote in his Patrology:

De praesciptione haereticorum is by far the most finished, the most characteristic, and the most valuable of Tertullian’s writings. The main ideas of this treatise have won for it enduring timeliness and admiration. Although it can be assigned no definite date, it was quite obviously written when the author was still on the best of terms with the Catholic Church, probably around the year 200 A.D. (p. 272)

Defining Orthodoxy

The “fall of the church” was one of several arguments used by early heretics to draw people away from the Church. To understand these errors it is important to understand the way early Christians understood orthodoxy. In the early Church orthodoxy (right doctrine) was based on apostolicity. Apostolicity meant that a local church was able to trace its teachings back to the original Apostles via the traditioning process.

Tertullian wrote:

It remains, then, that we demonstrate whether this doctrine of ours, of which we have not given the rule, has its origin in the tradition of the apostles and whether all other doctrines do not ipso facto proceed from falsehood. (Prescription 21; italics in original; bold added).

. . . and after first bearing witness to the faith in Jesus Christ throughout Judaea, and founding churches (there), they next went forth into the world and preached the same doctrine of the same faith to the nations. They then in like manner founded churches in every city, from which all the other churches, one after another, derived the tradition of the faith, and the seeds of doctrine, and are every day deriving them, that they may become churches. Indeed, it is on this account only that they will be able to deem themselves apostolic, as being the offspring of apostolic churches. (Prescription 20.4-6; emphasis added)

Here we see that the Great Commission is basically the transmission of Holy Tradition. This may come as a surprise to many Evangelicals who assume that the Apostles went out to all the nations with a leather bound Bible under their arms. But it needs to be kept in mind that all that the Apostles had were Christ’s teachings and deeds carefully memorized and stored in their hearts. Similarly, when they planted churches the early converts had to learn by heart the Apostles’ teachings. It would not be until decades later that the Gospels and the Epistles be written down on paper; and even then it would not be until centuries later that a formal collection known as the “New Testament” came to be recognized by the early Church. The biblical canon came about as the early bishops individually and in councils carefully scrutinized which early writings were indeed divinely inspired and apostolic.

In Tertullian’s time there were churches planted by the Apostles and there were churches that learned the Gospel from the first churches; both could claim apostolicity in light of the fact that they shared the same Apostolic Faith. Tertullian wrote:

Therefore the churches, although they are so many and so great, comprise but the one primitive church, (founded) by the apostles, from which they all (spring). In this way all are primitive, and all are apostolic, whilst they are all proved to be one, in (unbroken) unity, by their peaceful communion, and title of brotherhood, and bond of hospitality, —privileges which no other rule directs than the one tradition of the selfsame mystery. (Prescription 20.7-8; emphasis added)

In Tertullian’s time Christianity did not have an elaborate set of institutions like seminaries, bookstores, bible camps, and TV stations. Basically, early Christianity consisted of the local church under the leadership of the bishop, the successor to the Apostles. For Tertullian one indicator of theological orthodoxy was being able to trace one’s bishop’s succession back to the original Apostles.

But if there be any (heresies) which are bold enough to plant themselves in the midst of the apostolic age, that they may thereby seem to have been handed down by the apostles, because they existed in the time of the apostles, we can say: Let them produce the original records of their churches; let them unfold the roll of their bishops, running down in due succession from the beginning in such a manner that [that first bishop of theirs ] bishop shall be able to show for his ordainer and predecessor some one of the apostles or of apostolic men,— a man, moreover, who continued steadfast with the apostles. (Prescription 32; emphasis added)

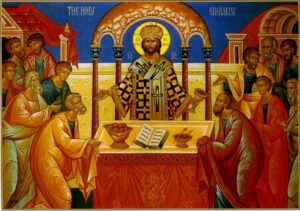

Just as significant is the importance Tertullian placed on the Eucharist as proof of orthodoxy: to be doctrinally orthodox was to be in communion with the apostolic churches. In the early church the claim was made that the teachings one heard at the weekly Eucharist were the same one as that taught by the original Twelve.

We hold communion with the apostolic churches because our doctrine is in no respect different from theirs. This is our witness to the truth. (Prescription 21)

In summary, Tertullian’s description of early orthodoxy consisted of: (1) the traditioning process, (2) the local bishop as successor to the Apostles, and (3) the Eucharist as the sign of doctrinal unity.

Holy Tradition or Sola Scriptura?

Tertullian advanced a number of arguments that would make a Protestant’s hair stand. In Prescription 19.1 he opens with: “Our appeal, therefore, must not be made to the Scriptures. . . .” Unlike Protestants who view Scriptures as a level playing field that anyone can read and anyone can interpret according to their conscience, Tertullian viewed Scripture as part of the sacred deposit entrusted to Church, recognized by the Church, and safeguarded for future generations by that same Church.

For wherever it shall be manifest that the true Christian rule and faith shall be, there will likewise be the true Scriptures and expositions thereof, and all the Christian traditions. (Prescription 19.3; italics in original)

There is no shred of evidence of Protestantism’s sola scriptura in Tertullian’s Prescription. What we find is the oral Tradition supplemented by written Tradition, and the two complementing the other.

Now, what that was which they preached—in other words, what it was which Christ revealed to them—can, as I must here likewise prescribe, properly be proved in no other way than by those very churches which the apostles founded in person by declaring the gospel to them directly themselves, both viva voce, as the phrase is, and subsequently by their epistles (Prescription 21.3; italics in original; bold added)

The early Christians never separated the two but saw the oral and the written forms of Tradition as integral to each other. Naturally, the oral form of the Apostolic teaching preceded the written form and continues to this day to inform the Church’s understanding of the New Testament text. In other words, early biblical exegesis was rooted in oral Tradition and did not arise from an independent objective reading of the Scripture text. It was a ecclesial activity, and not something carried out independently of the Church and its bishops.

Early Attacks on Orthodoxy

The early heretics used a variety of arguments designed to undermine the faith of the early Christians. The heresies are all aimed at attacking the notion of apostolicity. They make sense if orthodoxy is grounded in the traditioning process; but don’t make sense if early orthodoxy is based on sola scriptura.

Heresy # 1 – Christ had Other Apostles (Prescription 21)

Heresy #2 -– The Apostles Didn’t Know All There Was to Know (Prescription 22.2)

Heresy #3 – The Apostles Knew All There Was to Know But Chose to Hold Some Things Back (Prescription 22.2)

Heresy #4 – Peter’s Knowledge of the Gospel Inferior to Paul’s (Prescription 23 & 24)

Heresy #5 – Paul’s Knowledge of the Gospel Superior to Peter’s (Prescription 23 & 24)

Tertullian Refutes the “Fall of the Church” Heresy

Tertullian describes the “fall of the church” heresy:

. . .let us see whether, while the apostles proclaimed it perhaps, simply and fully, the churches, through their own fault, set it forth otherwise than the apostles had done. (Prescription 27.1)

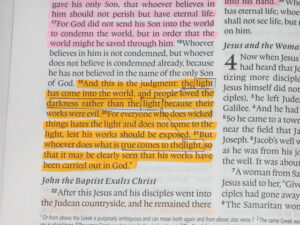

The early heretics cited Paul’s letter to the Galatians in support of the fall of the church theory: “O foolish Galatians, who hath bewitched you?” and “Ye did run so well; who hath hindered you?” They also pointed to Paul’s admonishment to the Corinthians about their being carnal and suited only for milk, not meat. Tertullian points out that the heretics failed to take into account that the early churches likewise responded to Paul’s correction. In addition, Tertullian pointed to Christ’s promise of the Holy Spirit guiding the Church “into all truth” (John 14:26) as evidence against the fall theory.

Grant, then, that all have erred; that the apostle was mistaken in giving his testimony; that the Holy Ghost had no such respect to any one (church) as to lead it into truth, although sent with this view by Christ, and for this asked of the Father that He might be the teacher of truth; grant, also, that He, the Steward of God, the Vicar of Christ, neglected His office, permitting the churches for a time to understand differently, (and) to believe differently, what He Himself was preaching by the apostles,—is it likely that so many churches, and they so great, should have gone astray into one and the same faith? (Prescription 28.1; emphasis added)

In Chapter 28, Tertullian points out the implication of the fall of the church heresy. It means a widespread apostasy among the early Christians and that even Paul was mistaken in his witness to the Gospel. Furthermore, it means that John 14:26 was not fulfilled even though Christ promised that He would send the Holy Spirit to guide the Church. Furthermore, it implies that the third Person of the Trinity, the Holy Spirit, the “Vicar of Christ” failed to do his job and that Christ made a false promise!

Tertullian points out that if the “fall of the church” theory held true then the churches would have diverged significantly from the teachings of the Apostles and that in turn would have resulted in theological divergences among the churches. But theological divergences were not to be found among the churches but with the heretics.

Error of doctrine in the churches must necessarily have produced various issues. When, however, that which is deposited among many is found to be one and the same, it is not the result of error, but of tradition. Can anyone, then, be reckless enough to say that they were in error who handed on the tradition? (Prescription 28.2-4)

Where diversity of doctrine is found, there, then, must the corruption both of the Scriptures and the expositions thereof be regarded as existing. On those whose purpose it was to teach differently, lay the necessity of differently arranging the instruments of doctrine. (Prescription 38.1-2)

Tertullian notes that where error results in fragmentation, orthodoxy results in doctrinal uniformity (unity) among the early Christians. Doctrinal unity flows from fidelity to the traditioning process used by the Apostles in transmitting the Gospel.

Tertullian sketches out what the “fall of the church” would have looked like if it did in fact happen:

During the interval the gospel was wrongly preached; men wrongly believed; so many thousands were wrongly baptized; so many works of faith were wrongly wrought; so many miraculous gifts, so many spiritual endowments, were wrongly set in operation; so many priestly functions, so many ministries, were wrongly executed; and, to sum up the whole, so many martyrs wrongly received their crowns! (Prescription 29.3)

In other words (at least in Tertullian’s mind) it is unthinkable and ludicrous to suppose that all the good things done by the early Christians were in fact bad things. Also, Tertullian points out that if such a massive defection had occurred then one logical consequence would be doctrinal pluralism. To put it another way, it does not make sense that so many Christians would have gone wrong all in the same direction at the same time!

Tertullian Compared With Irenaeus of Lyons

Where Tertullian’s standing as a church father is in question, the same cannot be said of Irenaeus of Lyons who is considered to be the greatest theologian of the second century. Tertullian and Irenaeus were contemporaries having lived in the latter half of the second century.

While Tertullian’s apologetics strategy In Prescription Against Heretics may strike Protestants as somewhat odd, it bears strong resemblance to Irenaeus’ Against Heresies. A comparison between the two shows strong similarities in the way they understood early orthodoxy: (1) both assumed doctrinal orthodoxy to rest on Apostolic Tradition (Prescription 20.4-6; Against Heresies 3.1.1), (2) both understood Apostolic Tradition to exist first in oral then in written form (Prescription 21.3; Against Heresies 3.4.2), (3) both taught that orthodox churches were those who could trace their bishop’s succession back to the original Apostles (Prescription 32.1; Against Heresies 3.3.1), and (4) both asserted that a key sign of doctrinal orthodoxy is the unity of faith among Christians (Prescription 20.7-8; Against Heresies 1.10.1).

Tertullian taken together with Irenaeus gives us valuable insight into the theological method of the early Church. Their theological method bears a striking resemblance to the Orthodox Church but also striking disparity with the theological method(s) of Protestantism.

Conclusions

The “fall of the church” heresy was not unique to Protestants but something that the early Church had to contend with as well. Protestants have used the “fall” as a way of justifying their breaking away from the Church of Rome, and the early heretics used it as a way creating an opening so they could present their alternative gospel to their listeners.

Tertullian refuted the “fall of the church” theory on four grounds: (1) biblical – it implied the failure of the Holy Spirit to guide the Church “into all truth” which in turn implied the failure of Christ’s promise in John 14:26, (2) theological – it implied the denial of divine sovereignty, (3) sociological – if true the fall of the church would have resulted into doctrinal fragmentation which flies in the face of the doctrinal unity shared by early Christians, and (4) historical –there was no evidence of a massive defection among early Christians.

Tertullian’s refutation of the “fall of the church” heresy is instructive for Orthodox-Reformed dialogue. It sheds light on how orthodoxy was understood in the early Church. In early Christianity orthodoxy was premised on apostolic succession and fidelity to the traditioning process resulting from a continuing Pentecost via the Holy Spirit. Capital “O” Orthodoxy today claims this same basis for its claim to be the true Church founded by Christ and his Apostles.

Protestants have an understanding of apostolicity different from Tertullian’s. The Protestant principle of sola scriptura assumes that apostolicity resides in the apostolic authorship of the New Testament and that Scripture is sufficient in itself to guarantee right doctrine. With the exception of the Anglicans, the vast majority of Protestants reject apostolic succession as a marker of orthodoxy.

One of the biggest challenges that Tertullian’s Prescription poses to Protestantism is his claim that heresy results in doctrinal diversity. This is especially daunting in light of the multitude of Protestant denominations. There are some Protestants who might point out differences even among some of the Apostolic Fathers, as if this disproves Tertullian’s claim to unity. What do we say to this? Was Tertullian’s sense of broad unity among the early churches wrong? Was there, as these Protestants must establish, a doctrinal free-for-all among the early churches? No, the early Christians’ unity in the Pentecost promise of the Holy Spirit was real and Tertullian was right. What differences that existed were largely minor for the Church as a whole and did not disrupt the Eucharistic unity among the early Christians. If there was no “fall of the church” in early Christianity then Protestants will need to reconsider their insistence on the need for the reform of the Church. Orthodoxy claims that in light of the fact that it has faithfully kept the Apostolic Tradition Protestants need look no further for the primitive apostolic Church described by Tertullian.

Robert Arakaki

Source

Tertullian. 1980. “The Prescription Against the Heretics.” In The Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol. III, pp. 243-265. Reprinted 1980. Translators: Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson. Wm. B. Eerdmans Press: Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Irenaeus of Lyons. 1985. “Against Heresies.” In The Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol. I, pp. 315-567. Reprinted 1985. Translators: A. Cleveland Coxe. Wm. B. Eerdmans Press: Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Quasten, Johannes. 1986. Patrology. Volume II. The Ante-Nicene Literature After Irenaeus. Christian Classics, Inc.: Westminster, Maryland.

Recent Comments