Hagia Sophia – Church of Holy Wisdom

I recently read Jason Stellman’s explanation for why he decided to head towards Rome. As I read through his “I Fought the Church, and the Church Won” I was struck by the absence of any mention of the Eastern Orthodox Church. It is as if he had no awareness of the other major non-Protestant option – the Eastern Orthodox Church.

Rather than critique Stellman’s reasons for becoming Catholic, I will be describing a side story of my journey to Orthodoxy. I did not default to Roman Catholicism simply because it was convenient, or because it was a readily accessible option, or because of the persuasive arguments presented by a brilliant convert to Catholicism. By God’s patience and gentle mercies, I slowly and carefully explored both the Roman Catholic and Orthodox possibilities. I took my time – 7 years — to really understand them both, before committing myself to the Orthodox Church.

Early Encounters with Catholicism

Early on as an Evangelical I found myself caught up in the controversy over the baptism in the Spirit and the charismatic gifts. I was uncomfortable with the extremes of Pentecostalism, but found much of the Evangelical anti-charismatic arguments unconvincing. But when I read the literature from the Catholic charismatic renewal I found there a spiritual balance and theological sophistication lacking among Protestants.

As a curious and voracious reader I read spiritual classics like John of the Cross’ Ascent on Mt. Carmel, Augustine’s Confession, and St. Francis’ Little Flowers. As my interest in Catholicism grew I began to look into the official teachings of the church, e.g., Documents of the Vatican II edited by Walter Abbott and John Hardon S.J.’s The Catholic Catechism. While I found the literature interesting, I also found them alien and exotic. It was like looking over a high wall and looking into a strange house next door. I continued to be happy to remain an Evangelical.

The 70s and 80s were a time when divisions between Protestantism and Catholicism began to soften. I found myself subscribing to both Christianity Today, the leading magazine for Evangelicals, and New Covenant, the flagship magazine for the Catholic charismatic renewal. In New Covenant I found articles about personal conversion to Christ, life in the Spirit, and faithfulness to the church. I found much to admire in the newly elected Pope John Paul II. I thoroughly enjoyed reading his encyclical Dives in Misericordia Dei (Rich in Mercy) which I thought could have been written by an Evangelical theologian.

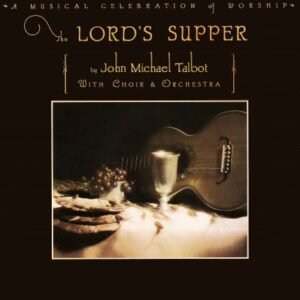

The 80s was also a time when John Michael Talbot, a former Evangelical musician turned Franciscan friar, released several albums that spanned the musical worlds of Evangelicalism and Catholicism. These included his Light Eternal, The Lord’s Supper, and Troubadour of the Lord. The Lord’s Supper was the Catholic Mass set to contemporary folk music. It highlighted the beauty and dignity of liturgical worship, something I rarely experienced as an Evangelical. This was before the ancient-future worship movement emerged within Evangelical circles.

The 80s was also a time when John Michael Talbot, a former Evangelical musician turned Franciscan friar, released several albums that spanned the musical worlds of Evangelicalism and Catholicism. These included his Light Eternal, The Lord’s Supper, and Troubadour of the Lord. The Lord’s Supper was the Catholic Mass set to contemporary folk music. It highlighted the beauty and dignity of liturgical worship, something I rarely experienced as an Evangelical. This was before the ancient-future worship movement emerged within Evangelical circles.

So why didn’t I become a Roman Catholic? One reason was that I didn’t want to abandon friends in the Evangelical circles. Another reason was my study of Mercersburg Theology which turned me into a Catholic and Reformed Evangelical. I innocently and sincerely believed I could be rooted in the Reformed tradition while exploring the riches of the early Church and ancient liturgies. With Mercersburg Theology I could enjoy the best of both worlds on my own terms. This was a time of childlike innocence before I came to grips with the radical and costly discipleship taught by the early Church.

Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary

When I came to Gordon-Conwell in the early 1990s, the theological and spiritual currents running through Protestant Evangelicalism were already shifting in subtle and surprising ways. In my first week at seminary I was surprised to see an icon of Christ hanging on a student’s door in Main Dorm. Later I met a fellow seminarian who converted to Catholicism while at Gordon-Conwell! Gary and I met for coffee to discuss his conversion. When I asked him for his reasons for the supremacy and infallibility of Pope I found his answers less than compelling.

While at Gordon-Conwell I was deeply involved in the Evangelical renewal movement in the United Church of Christ. Soon after I arrived at seminary I was invited to a meeting of UCC pastors. I remember standing with the pastors and being slightly bewildered by the dark mutterings about some guy named Scott Hahn, apparently he did something terrible like becoming a Roman Catholic. I have never met Scott Hahn but I am deeply indebted to him. Once when I was wrestling with the doctrine sola scriptura, the question popped into my head: Did the Bible ever teach sola scriptura? I couldn’t come up with a convincing answer which led to the question: So how did the leading Evangelical theologians deal with this? A few days later I bought a tape by Scott Hahn and got my answer; none of the leading Evangelical theologians have been able to answer this question! [See my blog posting on the biblical basis for Holy Tradition.]

Catholicism in Liberal Berkeley

UC Berkeley

After Gordon-Conwell, I headed to Berkeley to do doctoral studies in history of religions at the Graduate Theological Union.

I came to Berkeley a post-Evangelical open to change. By then I had become weary of the fluidity and superficiality in Evangelical theology. During my first year, I found myself drawn to the rich liturgical tradition of Roman Catholicism. This attraction to Roman Catholicism held my attention for a short while until I was providentially introduced to Eastern Orthodoxy.

Taize style worship

In my first year, the candlelight Mass at the Newman Center was my regular place of worship. It was a moving sight seeing the church filled with UC Berkeley students singing songs of worship in the soft glow of candles around the room. It was also profoundly edifying to be at a church where the center of Sunday worship was the Lord’s Supper.

But I also found it a jarring and sometimes disturbing experience. After becoming familiar with the pattern of worship, I noticed priests would drop parts of the Mass like the Nicene Creed and the Confiteor (the Prayer of Confession) which according to the official rubrics is not supposed to happen. Keep in mind that the Mass is not just a Sunday ritual but a powerful means of shaping the faith and spirituality of the Catholic masses. According to the theological principle of lex orans, lex credens (the rule of prayer is the rule of faith), the Mass forms the church in its faith and worship of God. But here it seemed that the Mass had become a flexible tool that reflected the individual whims of priests. In other words a have-it-your-way mentality among the Catholic clergy will eventually trickle down to the Catholics in the pews with devastating results. And when the service was over, I was often surprised to hear announcements for upcoming meetings for the Gay-Lesbian fellowship. I was coming face to face with the fact that real Catholicism was quite different from the official Catholicism I had been reading about. Cafeteria style Catholicism was a very real and uncomfortable reality I had to face up to in Berkeley.

In my third year, I rented a room at a Benedictine retreat house near the university. The monks there frequently talked about the need to unite Protestants with Catholics, and how they offered Holy Communion to Protestants as a gesture of unity. Once when I attended their service they gave me the opportunity to receive the Host but I declined. The reason I declined was because I had read an article by Fr. Edward O’Connor who explained that receiving Holy Communion in the Mass meant two things: (1) that one accepted the Catholic dogma of Transubstantiation and (2) that one accepted the teaching authority of the Pope, that is, one was willing to come under the Pope. My Catholic friends thought church unity easy to pull off, but I was very conscious of the big price tag attached to the Communion wafer. [See the Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd edition) §1354, §1369, and §1374.]

In my second year in Berkeley, I discovered a tiny Bulgarian Orthodox Church that met across the street from the university. For nearly two years I attended the Orthodox Liturgy. It was good that the Liturgy was all in English. Up till then I had found mixed language liturgies to be off putting and incomprehensible. At Saints Kyril and Methodios I found myself drawn by the Liturgy. After a long hard week of intense studying, I found it soothing and healing to stand during the Liturgy and let the ancient prayers flow over my soul. It was a formative time for me spiritually. I became immersed in the flow of the Liturgy and after a while became familiar with the pattern of the Liturgy. There were no surprises like at the Newman Center. I came away with two powerful impressions: (1) what I saw at this tiny Orthodox parish matched what I was reading and (2) Orthodoxy was capable of withstanding the liberal ethos of Berkeley.

From Post-Evangelical to Orthodoxy

I very much appreciate my time at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. Having studied there I can say that I know firsthand the best of Evangelical scholarship. However, my time there was when fine hairline cracks began to appear in my Evangelical theology. In time the tiny cracks became major fissures leading to a theological crisis especially over sola scriptura then sola fide. Yet as my Protestant theology began to fall apart I found myself increasingly drawn to Eastern Orthodoxy instead of Roman Catholicism. Below are some of my reasons:

- There is no evidence of the Bishop of Rome as the supreme head and infallible magisterium in the early Church. The current form of a supreme and infallible Pontiff is a recent innovation!

- The Papacy’s autonomy from the ancient Pentarchy violates early Christian unity. The Rome versus Constantinople frame falls flat in light of the fact that the other major patriarchates sided with Constantinople.

- For all the elaborate rationales advanced by Catholics to justify the Filioque, it is an indisputable fact that the Papacy’s unilateral insertion of the Filioque into the Nicene Creed runs contrary to the conciliarity intrinsic to the seven Ecumenical Councils. Canon VII of the Council of Ephesus instructs:

When these things had been read, the holy Synod decreed that it is unlawful for any man to bring forward, or to write, or to compose a different (ἑτέραν) Faith as a rival to that established by the holy Fathers assembled with the Holy Ghost in Nicæa. (Source)

- What we understand to be the Catholic Church is really the Medieval Catholic Church, a product of the Middle Ages and the Scholastic movement. The doctrines of purgatory and indulgences are medieval innovations that have no basis in patristic theology. This helped explain the gap between the Roman Catholic Church and the early Church. It also helped me to view with sympathy Protestants as innocent victims of Rome’s willful aberrations.

- The dogma of Transubstantiation is a doctrinal aberration that is at odds with the patristic consensus.

- The Novus Ordo Mass (the Vatican II Mass) marks a major break in the Catholic Church’s liturgical continuity with the early Church.

In addition to the above theological issues were the practical issues based on what I mentioned earlier. The liberal Catholicism in Berkeley was not a fluke but part of larger struggle taking place in Catholicism. Ralph Martin’s A Crisis of Truth describes in some detail the attempt by priests, theologians, and laity to redefine the Catholic faith. As an Evangelical in a liberal Protestant denomination, I did not want to go through that painful experience again. I was also struck by the fact that while Catholicism claims to be one church, what I had seen pointed to a church that operated on two quite different parallel realities.

Protestants at the Crossroads

An Evangelical who finds himself in the midst of the rubble of a shattered Protestant theology needs to consider carefully what his options are. There exist not one but two options. The Church of Rome may claim to have been founded by the Apostles Peter and Paul, but the same claim can be made by the Church of Antioch (see Acts 13:1 for Paul and Galatians 2:11 for Peter and Paul). So while the Church of Rome may seem to be most obvious option there is another option. But there is another historically and biblically sound option: the Church of Antioch, that is, the Eastern Orthodox Church. The Church of Antioch can claim a chain of apostolic succession that is equally valid and older than Rome’s. The early Councils did not assign the Bishop of Rome an authority greater than the other bishops. Rome’s claim to supremacy over the other bishops and patriarchates is a later development and is at odds with the canons of the Seven Ecumenical Councils.

An Evangelical who finds himself in the midst of the rubble of a shattered Protestant theology needs to consider carefully what his options are. There exist not one but two options. The Church of Rome may claim to have been founded by the Apostles Peter and Paul, but the same claim can be made by the Church of Antioch (see Acts 13:1 for Paul and Galatians 2:11 for Peter and Paul). So while the Church of Rome may seem to be most obvious option there is another option. But there is another historically and biblically sound option: the Church of Antioch, that is, the Eastern Orthodox Church. The Church of Antioch can claim a chain of apostolic succession that is equally valid and older than Rome’s. The early Councils did not assign the Bishop of Rome an authority greater than the other bishops. Rome’s claim to supremacy over the other bishops and patriarchates is a later development and is at odds with the canons of the Seven Ecumenical Councils.

Two Peas in a Pod?

As the crisis in Evangelicalism intensifies, many Evangelicals will find themselves in a state of vertigo and confusion. They must not make the mistake of thinking that Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy are two peas in a pod. The two may look superficially similar but under the surface are profound differences. One crucial difference is the way they do theology. The Roman Catholic Church bases its theology on the infallible Pope. The Pope is the monarch of the Catholic Church. According to Catholic theology the Pope can unilaterally amend the Nicene Creed, order sweeping changes in the Sunday Mass, and issue dogmas — essential and non-negotiable doctrines binding on all members of the Catholic Church.

As the crisis in Evangelicalism intensifies, many Evangelicals will find themselves in a state of vertigo and confusion. They must not make the mistake of thinking that Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy are two peas in a pod. The two may look superficially similar but under the surface are profound differences. One crucial difference is the way they do theology. The Roman Catholic Church bases its theology on the infallible Pope. The Pope is the monarch of the Catholic Church. According to Catholic theology the Pope can unilaterally amend the Nicene Creed, order sweeping changes in the Sunday Mass, and issue dogmas — essential and non-negotiable doctrines binding on all members of the Catholic Church.

The theological method of Eastern Orthodoxy is based on Apostolic Tradition. Both clergy and laity have been entrusted with guarding and passing on Holy Tradition (II Thessalonians 2:15, II Timothy 2:2). The Orthodox theological method is based on Christ’s promise that he would send the Holy Spirit to guide the Church into all truth (John 16:13). Unlike Catholicism which rests on one man (the Pope), Orthodoxy does theology collegially, that is, as a body working in unity. In Acts 15 we read how the early Church came together and under the guidance of the Holy Spirit resolved a major theological crisis. There was no evidence of a unilateral papal decree here! Acts 15 provides the biblical basis for the Seven Ecumenical Councils, a key component of Orthodoxy. It is important for Evangelicals to remember that they owe their core Christological and Trinitarian doctrines to the Ecumenical Councils. The Bishop of Rome collaborated and supported these Councils. He exercised authority with the Ecumenical Councils, not over them. The theological unity of the early Church was conciliar, not papal.

One thing that struck me about Orthodoxy was the continuing relevance of the Seven Ecumenical Councils to current debates within Orthodoxy. One example is Canon 28 of the Council of Chalcedon and the role of Patriarch of Constantinople with respect to the modern Orthodox diaspora. When I read Roman Catholic literature the overall sense I got was that the Ecumenical Councils belonged to an earlier stage of development and that the Catholic Church had evolved to another level. I sensed a subtle disconnect between the Catholic Church and the early Church.

Advice for the Lost — Retrace Your Steps

My advice to Protestants standing at the crossroads looking at the Catholic and Orthodox options is to do what people often do when they realize they are lost – retrace your steps. Read the book of Acts, then the Apostolic Fathers and Eusebius’ Church History. Study how Irenaeus of Lyons combated the heresy of Gnosticism. Also study the Arian controversy and the making of the Nicene Creed. Become familiar with the early Church before the Schism of 1054. I also recommend they read the fourth century Catechetical Lectures by Patriarch Cyril of Jerusalem which describe the Holy Week services in Jerusalem. When I read Cyril’s lectures I was struck by how much they can be used to describe the Holy Week services of Orthodoxy today. I don’t think the contemporary Roman Catholic approach to Lent and Easter much resembles the liturgical celebrations of the early Church.

My advice to Protestants in the middle of a theological crisis is this: Don’t rush, take your time. Carefully study the Church Fathers, learn the ancient liturgies, and unlearn the modern habits of thought which have entangled the minds so many Protestants and Evangelicals. Then ask yourself which church today bears a closer resemblance to the early Church.

You Must Give Up Your Catholicism

A Protestant ran up eagerly to an Orthodox priest and asked: “Father, what must I do to become Orthodox?” The priest answered: “You must give up your Roman Catholicism.” That anecdote made a powerful impression on me for it illustrated how much Protestantism has in common with the Roman Catholic Church. Protestantism has its origins as a reaction to medieval Catholicism. This probably explains why modern day Protestants who seek to recover a historic and sacramental theology have started wearing Roman Catholic collars and white robes. Many will incorporate the “ancient” Nicene Creed into their church services, not realizing that they are using the version that has been tampered with by the Pope. The Nicene Creed endorsed by the Ecumenical Councils did not have the Filioque clause (“…and the Son”). These small “c” catholic Protestants have unwittingly biased themselves towards Roman Catholicism.

If one wants to go beyond medieval Catholicism to the early Church Fathers one must study the Church prior to the Schism of 1054. A Protestant who lays aside not only their Protestant innovations but also the accretions from medieval Catholicism will be able to accept Holy Tradition as given by Christ to his Apostles and which has been faithfully safeguarded by Eastern Orthodoxy for the past two millennia. This is the Pearl of Great Price. It is recommended that the reader read Prof. Jaroslav Pelikan’s excellent The Vindication of Tradition which explores the value of tradition for the Christian faith and his five-volume The Christian Tradition which is likely the best work on historical theology today.

The Tragedy of the Best Kept Secret in America

Ethnic Festival

So, why did Jason Stellman make no mention of Orthodoxy? Sadly, I believe that he has not taken the time needed to become acquainted with the Orthodox Church by attending her Liturgy (Sunday worship services), sitting down with her priests, talking things over with former Protestants who became Orthodox finding out from them how the wisdom of the ancient Church can be found in Orthodoxy today.

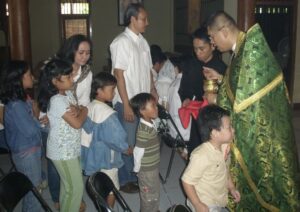

It is also a sad fact that many Americans have no awareness of Orthodoxy’s presence in America. Much of this ignorance can be attributed to Orthodox Christians themselves. We need to increase Orthodoxy’s public profile. We need to go beyond ethnic festivals and ethnic parishes with Sunday services in incomprehensible languages. We need Orthodox priests who like John Wesley have an evangelistic outlook:

I look on all the world as my parish; thus far I mean, that, in whatever part of it I am, I judge it meet, right, and my bounden duty, to declare unto all that are willing to hear, the glad tidings of salvation.

Orthodoxy in America needs to take our candle out from under the bowl and put it on a lamp stand for all to see.

You – the Orthodox Church – are the light of the world. A city on a hill cannot be hidden. Neither do people light a lamp and put it under a bowl. Instead they put it on its stand, and it gives light to everyone in the house. (Matthew 6:14-15 paraphrased).

Metropolitan Philip

We need bold visionary Orthodox hierarchs like Metropolitan Philip who proclaimed: Come home America! His Eminence also rebuked the Orthodox for making “Orthodoxy the best kept secret in America” because of their laziness and their being “busy taking care of their hidden ethnic ghettoes.”

It is time for Orthodoxy to stop being the hidden option for inquiring seekers. People need to see the light of our Faith and to find a welcoming hand of greeting at the doorsteps of our churches.

Robert Arakaki

See also:

Michael Whelton’s journey from Roman Catholicism to Orthodoxy.

The Orthodox Christian Information Center’s page “Orthodoxy and Western Christianity: For Roman Catholic.”

Recent Comments