Maria Lago Studio “Exodus” Source

In Rev. Peter Leithart’s recent column for First Things: “The tragedy of conversion” (7 October 2013), he describes as tragic Protestants who acquired the taste for “catholicity and unity” and instead of remaining Protestant go so far as to convert to the Orthodox Church or to Rome. This is a crisis affecting Protestantism in general and the Federal Vision movement in particular. The New York Times published an article in 2009 about this trend: “More Protestants Find a Home in Orthodox Antioch Church.”

The recent exodus while not large in number is significant. Scott Hahn, a former Presbyterian seminary professor, wrote about his conversion in Rome Sweet Home. Other notable converts include Thomas Howard and Francis Beckwith, former president of the Evangelical Theological Society. More recently, a certain amount of controversy surrounded Jason Stellman. Ironically, it was Pastor Stellman whom the PCA assigned to be the lead prosecutor for Leithart’s heresy trial!

On the Eastern Orthodox side the late Peter Gillquist tells the story how he and his fellow Campus Crusade for Christ co-workers became Orthodox in his book Becoming Orthodox. Clark Carlton is a former Baptist seminarian and Matthew Gallatin a former Calvary Chapel pastor. Frank Schaeffer, son of the famous Evangelical thinker, Francis Schaeffer, converted to Orthodoxy. One prominent convert is the late Jaroslav Pelikan, world renowned Yale University professor who authored the five volume The Christian Tradition. Michael Hyatt, former CEO of Thomas Nelson Publications and a former ruling elder in the PCA, is now a deacon serving the Orthodox Church.

When one looks at the kind of people exiting Protestantism, we see some of the most seasoned, serious, and brightest people of the Evangelical world: seminarians, seminary professors, pastors, authors, publishers, leaders of leading Evangelical organizations. One has to ask: What is going on here!?!

My assessment is that Protestantism having lost its theological center has become a fractured and confusing, if not volatile and unstable. Troubled by this state of confusion many are seeking refuge in the historic early Church. This is the backdrop to Leithart’s recent column.

Protestantism’s Meltdown

In the first half of the twentieth century American Protestantism was divided principally between liberals and conservatives. Then in the 1950s and 1960s there was an influx of Pentecostalism into historic mainline Protestant churches. The 1970s marked the beginning of the shift to post-denominational Protestantism. More recently, American Protestantism saw the rise of mega churches whose seeker friendly services downplayed doctrine. Church shopping became the new normal as people began to evaluate churches in terms of the services they had to offer instead of their teachings.

An ironic reaction to all this has been a growing ancient-future movement that sought to rediscover their roots in ancient Christianity. Soon Evangelicals began having processions with acolytes carrying crosses, clergy wearing vestments, reciting the Nicene Creed, quoting early church fathers, and holding weekly Eucharist. This return to the roots movement took several forms. One was the Emergent Movement which attempted to be post-modern and eclectic in worship and doctrine. Another was the Canterbury trail movement where people joined one of the various Anglican off-shoots from Episcopalianism.

Peter Leithart is part of the Federal Vision (FV) movement, a high church expression of Reformed theology that seeks to give greater emphasis to covenant theology, Trinitarian thinking, and the sacraments of baptism and Holy Communion – as did many if not most of the early Reformers.

Leithart and his FV colleagues believe themselves to be on the cutting edge of “the-future-church” and much closer to getting it right than say the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA) or the Orthodox Presbyterian Church (OPC). In actuality, they are just another “new-and-improved” Reformed splinter group. For them, a Christian moving from an older Protestant denomination–Methodist, Baptist, Anglican, or mainline Reformed—to the Federal Vision would be making a wise move in the right direction.

Given the peculiar way the FV folks understand “catholicity and unity,” it is no surprise that they think a Protestant converting to Orthodoxy is going in the wrong direction. An even bigger problem for them is knowledgeable Reformed Christians from the Federal Vision jumping ship! There is a quiet exodus from the FV to Orthodoxy under way right now. This is the growing crisis that the Rev. Peter Leithart is trying to head off.

A former PCA elder, currently an Orthodox catechumen, explained to me the implicit insult in his move towards Orthodoxy: “What! You actually believe the Apostles and their disciples got the Faith right centuries ago . . . before our FV insights . . . . Grrrrr!!” What adds to their grief and distress is that Pastor Leithart and his mentor Pastor James B. Jordan were two of the prominent CREC & PCA leaders who cracked open the door for their bright and zealous disciples to inquire into historic Orthodoxy with the unexpected results of some converting to Orthodoxy! Now, they are writing articles like this one in an effort at damage control. It seems to me that what Rev. Leithart is trying to do is keep people from straying off the Protestant reservation.

Leithart’s Theology of Time

Leithart’s opposition to Protestants converting to Orthodoxy stems from his understanding church history.

He writes:

Apart from all the detailed historical arguments, this quest makes an assumption about the nature of time, an assumption that I have labeled “tragic.”

It’s the assumption that the old is always purer and better, and that if we want to regain life and health we need to go back to the beginning (Emphasis added).

Leithart sees church history as progressive and dialectical. For him, early Christianity was just the beginning of a long evolutionary journey and that the mature church of Protestantism is to be preferred over the infancy of early Christianity. To dissuade Protestants from converting to Orthodoxy Leithart argues that the true Church is not to be found among the Protestants, Catholics, or Orthodox but ahead of us in the future. He writes:

History is patterned in the same way. Eden is not the golden time to which we return; it is the infancy from which we begin and grow up. The golden age is ahead, in the Edenic Jerusalem.

This evolutionary approach to church history is congruent with postmillennialism favored by Reformed theologians. It reminds me of Mercersburg Theology’s Philip Schaff who posited that church history is the outworking of a Hegelian dialect, that over time division will be resolved into deeper unity, and that over time heresy and error will be resolved into deeper truth. This is radically at odds with how Orthodoxy understands truth and what the Bible teaches.

Leithart’s portrayal of time is based on a false characterization of the Orthodox understanding of time. Time is not the issue here. The issue here is the promise of the Holy Spirit Christ made to His Apostles in the Upper Room discourse (John 13-16). Was the coming of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost to be a brief flash of inspiration for the Apostles and their disciples? Or did the Holy Spirit come to inhabit the Church permanently, “abide with you forever” (John 14:16)? For the Orthodox these are not difficult questions. Christ’s promises were proven true not only in the book of Acts but in subsequent church history. For Orthodox Christians the Holy Spirit guided the early Church through the Ecumenical Councils and continues to guide the Church. This is very different from the Blinked-Out/Blinked-On theory of church history prevalent among Protestants. This theory assumes that the light went out in the early Church and did not come back on until the Protestant Reformation. The Orthodox understanding of Holy Tradition and the Bible arising out of Holy Tradition means that the Apostles got their teachings directly from Christ and the Holy Spirit. Neither Scripture nor Tradition are dependent on Rev. Leithart’s notion that time is the crucial factor or his implicit evolutionary assumption “new is always better.”

The Faith Once and for All Delivered to the Saints

The Bible rules out an evolutionary understanding of theology. We find in Jude 3:

Beloved, while I was very diligent to write to you concerning our common salvation, I found it necessary to write to you exhorting you to contend earnestly for the faith which was once for all delivered to the saints. (Emphasis added; OSB)

There are three important points made in this short verse. One, the word πιστει (pistei, faith) has the definite article which indicates that the writer has in mind a body of truth or a set of doctrines. This points to one true Faith, not multiple versions as would be assumed by Leithart’s theory of history. Two, the word παραδοθειση (paradotheise, aorist passive participle, delivered) points to a traditioning process. Reinecker’s Linguistic Key to the Greek New Testament has this to say about παραδοθειση:

The word is used for handing down authorized tradition in Israel (s. 1 Cor. 15:1-3; 2 Thess. 3:6), and Jude is therefore saying that the Christian apostolic tradition is normative for the people of God (Green). (p. 803)

The Christian Faith is not something discovered through rational study of the Bible or the result of creative engagement with culture, but received from the Apostles. Protestant theology with its sola scriptura assumes that Christian doctrine arises from the study of Scripture independent of Tradition. This is a novel theological method alien to that of the early Church Fathers. Three, the word ‘απαξ (hapax) points to a unique one-time revelation. The same word used in Hebrews 9:28 to describe Christ’s unique one-time sacrifice on the Cross. That one time revelation was the Incarnation of the Word of God in Jesus Christ. Jesus taught his Apostles the Faith they were to teach the nations. As recipients of the Apostolic Tradition we are obligated to safeguard it from change until the Lord returns at the Second Coming. Thus, if we take Jude 3 at face value we have no choice but to reject Rev. Leithart’s evolutionary approach to Christian doctrine.

Another telling and related bible verse few Protestants seem to notice is 2 Thessalonians 2:15: “Therefore, stand fast and hold the traditions which you were taught, whether by words or our epistle.” (Emphasis added; OSB) Note that the verb used here is “stand fast” (στηκεν), not to move ahead. This sense of standing one’s ground can be found in Paul’s use of the same Greek word in 1 Corinthians 16:13 and Galatians 5:1.

If one holds to the traditioning model of theology then antiquity becomes a very important criterion for theological orthodoxy. Antiquity is important, not because older is better but because antiquity is one of the distinguishing markers of apostolicity. Apostolicity without antiquity is sheer nonsense. That is why unbroken apostolic succession is so important. This leaves Protestants seeking the early Church with only two choices: acceptance of Orthodoxy’s Holy Tradition or submission to the Roman Pontiff. Anglicanism, despite its having bishops, because it originated from a schismatic break with Rome, cannot claim unbroken continuity.

Coming to Zion

The fundamental problem with Rev. Leithart’s approach to church history is his understanding of time as χρονος (chronos). It omits the understanding of history as καιρος (kairos). Because of the Incarnation of the divine Word, human history is no longer trapped by chronological time. Because the Kingdom of God has broken into human history the golden age Leithart longs for is present in the Liturgy. Orthodox worship involves the shift from chronos to kairos. Frederica Mathewes-Green describes in At the Corner of East and Now a typical Orthodox Sunday service:

This first service of the day is called the “Kairon,” from the Greek word for time. Not chronos, orderly measured time, but kairos, the right time, the moment-in-time, the time of fulfillment. Worship lifts us out of ordinary time into the eternal now. At the beginning of the Divine Liturgy, the deacon says to the priest, “It is time for the Lord to act.” (p. 15)

For Orthodoxy the golden era of Christianity is now. We are not moving towards Mount Zion, we are already at Mount Zion. We read in Hebrews 12:22-24:

But you have come to Mount Zion and to the city of the living God, the heavenly Jerusalem, to an innumerable company of angels, to the general assembly and church of the firstborn who are registered in heaven, to God the Judge of all to the spirits of just men made perfect, to Jesus the Mediator of the new covenant, and to the blood of sprinkling that speaks better things than that of Abel. (Emphasis added; OSB)

The first thing to note is the opening phrase “you have come.” The Greek for “have come” is προσεληλυθατε (proseleluthate) which is the perfect active indicative form of “come to” or “draw near.” The perfect means: you have already come to Mount Zion, not you will come one day in the future come to Mount Zion. This passage in Hebrews 12 describes what happens every time we celebrate the Divine Liturgy.

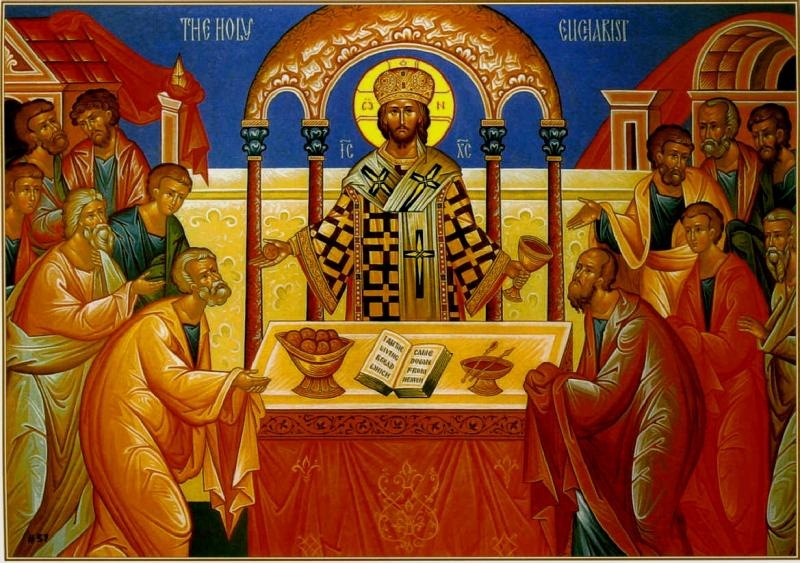

“The Lamb of God is broken and shared, broken but not divided; forever eaten yet never consumed, . . .”

The Church is the city of the living God, not in the process of becoming the city of God. In the Eucharist the local congregation gathers as the people of God to join in the eternal worship of heaven. As we transition into the second half of the Liturgy the Trisagion hymn reminds us that in the Eucharist we are surrounded by an innumerable number of angels. When I look around the church I see icons of the saints, “the spirits of just men made perfect.” As we go up for Holy Communion we see the communion chalice which contains the blood of Christ which speaks more powerfully than that of Abel’s. Thus, Hebrews 12:22-24 describes the Orthodox Liturgy. Gabe Martini notes in his response to Rev. Leithart:

In the Eucharistic fellowship of the Church, we are ever-united with all the Saints of history, both past and present. Our orientation is eschatological, and eschatology is not merely “the future,” in a strictly linear sense. This is nowhere more pronounced than in our celebration of the Eucharist, which is an event that points the faithful towards the east—not merely towards Eden or the beginnings of a nostalgic faith, but towards the great wedding feast of the Lamb. This is played out not only in our written tradition and services, but also in our iconography of the Mystical Supper, which shows both Jesus and the apostles not in a dingy upper room of first-century Palestine but at the table of the wedding feast in eternity.

Thus, if Rev. Leithart’s theological argument is flawed, then Protestants should give serious consideration to converting to Orthodoxy. Crossing the Bosphorus presents a way out of a current situation in Protestantism that Leithart described as “agonizing.” It involves leaving a sinking ship for a more structurally sound vessel. If Protestantism is a sinking ship, the real tragedy would be for one to go down with the ship and not help others cross over to a better, more stable and historic boat. I would urge Rev. Leithart and other Protestants to reconsider their position.

Thus, if Rev. Leithart’s theological argument is flawed, then Protestants should give serious consideration to converting to Orthodoxy. Crossing the Bosphorus presents a way out of a current situation in Protestantism that Leithart described as “agonizing.” It involves leaving a sinking ship for a more structurally sound vessel. If Protestantism is a sinking ship, the real tragedy would be for one to go down with the ship and not help others cross over to a better, more stable and historic boat. I would urge Rev. Leithart and other Protestants to reconsider their position.

The Blessings of Crossing Over

People convert for various reasons. Part of what prompted my converting to Orthodoxy was Protestantism’s theological incoherence. Despite the initial appeal of sola scriptura I found Protestantism’s lack of Tradition has resulted in hermeneutical havoc. My research led me to the unexpected conclusion that Protestantism’s hermeneutical chaos was intrinsic to sola Scriptura! When I discovered the Ecumenical Councils and the notion of Holy Tradition I found a stable framework for reading Scripture. One unanticipated blessing was Orthodoxy’s rich tradition of spirituality which taught me about the need for denying the passions the flesh and the cultivation of humility for spiritual growth in Christ. Another benefit in converting to Orthodoxy is that I found myself receiving the Eucharist in the same church as that of the ancient fathers like John Chrysostom, Basil the Great, Athanasius the Great, Cyril of Jerusalem etc. I find great comfort knowing that I am now in the one holy catholic and apostolic Church confessed in the Nicene Creed. I no longer find myself yearning to be part of that Church because I am now at home. I pray other yearning Protestants will find a home in the Orthodox Church.

Robert Arakaki

See Also

Rev. Peter Leithart: “Too catholic to be Catholic.”

Robert Arakaki: “Unintentional Schism? A Response to Peter Leithart’s ‘Too catholic to be Catholic.”

Robert Arakaki: “Crossing the Bosphorus.”

Recent Comments