An Orthodox Assessment

The Rev. Peter Leithart’s The End of Protestantism: Pursuing Unity in a Fragmented Church is more than an expanded version of his well known article “Too Catholic to be Catholic.” Leithart has brought a more nuanced and sophisticated level of analysis to his critique of Protestant denominationalism by drawing on social science literature. He has done more than criticize denominationalism; he has also provided concrete examples that exemplify his vision of a reunited Christianity. His writing style – passionate, scholarly, and eloquent – while easy to read, is not lightweight.

The Rev. Peter Leithart’s The End of Protestantism: Pursuing Unity in a Fragmented Church is more than an expanded version of his well known article “Too Catholic to be Catholic.” Leithart has brought a more nuanced and sophisticated level of analysis to his critique of Protestant denominationalism by drawing on social science literature. He has done more than criticize denominationalism; he has also provided concrete examples that exemplify his vision of a reunited Christianity. His writing style – passionate, scholarly, and eloquent – while easy to read, is not lightweight.

Leithart’s book deserves attention because he is on the forefront of a movement of Protestants seeking to reconnect with the Ancient Church while also addressing Protestantism’s tragic divisions. Another reason for an Orthodox assessment is that Leithart has included Orthodoxy in his quest for Christian unity. Indeed, Pastor Leithart even addresses part of the book to Protestants who increasingly are being drawn to Orthodoxy – curiously seeking to dissuade them from re-uniting with the historic Orthodox Church!

Breaking Ties With the Ancient Church

It is widely acknowledged that one of Protestantism’s fundamental problems is its divisions. While most Protestants agree that denominational divisions are not good – division, even divisiveness has historically been its dominant characteristic – starting from the very beginning with Luther, Calvin, and Zwingli. Protestants have taken several approaches to the problem of a divided Christianity. Many Evangelicals posit an invisible Church comprised of all true believers. What unites this invisible Church is not shared doctrine but the subjective “born again” experience. Another is the Branch Theory which holds that church unity is found in the three historic branches: Eastern Orthodoxy, Roman Catholicism, and Anglicanism.

Being a good Protestant, Leithart rejects the claims either of Roman Catholicism or Orthodoxy to be the true Church. As a high church Protestant, Leithart rejects the unity of the invisible Church. What Leithart proposes is that there will be a visible, unified Church in the future.

The unity of the church is not an invisible reality that renders visible things irrelevant. It is a future reality that gives present actions their orientation and meaning. Things are what they are as anticipations of what they will be (p. 19, italics in original; cf. p. 26).

This future-oriented ecumenism is not new. Gabriel Fackre – Andover Newton Theological School’s Samuel Abbott Professor of Christian Theology Emeritus – in an essay written in 1990 described the United Church of Christ’s ecumenism. This essay anticipated Rev. Leithart’s future oriented vision of church unity by 25 years.

Diversity is not the foe of doctrine. It stretches those who honor it toward catholicity. May we live out the enriching unity we have and toward a larger unity to come (Fackre p. 149; italics in original, bold added).

Pastor Leithart has an evolutionary understanding of the Church in which doctrine, practice, and worship evolve over time. The danger of Pastor Leithart’s solution is that it entails a parting of ways with the Ancient Church.

One weakness of Protestantism has been its wholesale neglect of church history, especially the first 1,000 years. The ironic tragedy of Leithart’s unified church of the future is that this church would have been rejected and excluded from Holy Communion by the early Church Fathers. Mercersburg theologian John Nevin in “Early Christianity” describes the estrangement between Protestantism and the Ancient Church:

The great Athanasius, now in London or New York, would be found worshipping only at Catholic altars. Augustine would not be acknowledged by any evangelical sect. Chrysostom would feel the Puritanism of New England more inhospitable and dry than the Egyptian desert (p. 271).

And, given the many changes that have taken place in recent decades, one has reason to wonder: How many modern day Evangelicals and Protestants would be welcome at the Eucharist in Luther, Calvin, and Bucer’s church? Readers of Leithart’s book should be aware of the high cost that comes with Leithart’s proposed solution: broken fellowship with the early Church.

A Protestant Solution

For all Pastor Leithart’s sweeping ecumenical vision, his solutions are surprisingly Protestant. Leithart gives with one hand, but then takes back with the other. At first he “retracts” certain Protestant positions then he quietly reinstates the same Protestant positions.

Mary will be honored as God-bearer. Saints will be celebrated. Church buildings will be bright and colorful. But in the reformed Catholic church, there will be no prayers to Mary, no appeals to the saints, no veneration of icons. . . . . Formerly Presbyterian and Baptist churches will paint their walls and put in stained glass (p. 32; emphasis added).

Pastor Leithart remains resolutely Protestant. This is evident in his flat out refusal to subject the Protestant Reformation to critical scrutiny.

The Reformation recovered central biblical and evangelical truths and practices that Protestants ought not to sacrifice. Even after Vatican II and the ecumenical movement, even after the joint Lutheran-Catholic statement on the doctrine of justification, many of the traditional Protestant criticisms of Catholicism and Orthodoxy (of the papacy, of Marian doctrines, of icon veneration, of the cult of the saints) hold (p. 169).

While many of the criticisms the Reformers directed against Roman Catholicism were valid, Protestants like Rev. Leithart need to come to terms with the fact that the Reformation took place in the 1500s, a long time after the early Church, and that it has introduced many doctrinal and liturgical innovations not found in the early Church. The discrepancy between Protestantism and early Christianity is something that Protestants must give account for.

So What’s New?

Reading Leithart’s book brought back memories of my former denomination the United Church of Christ (UCC). The future church which Pastor Leithart described with moving eloquence in Chapter 3 sounds much like the mild liberalism of the UCC in the 1950s and the 1960s. In line with the title of his book, Rev. Leithart calls for Protestant denominations and churches to “die,” that is, to cease to exist in their present forms in order for new forms to emerge. He writes:

Reading Leithart’s book brought back memories of my former denomination the United Church of Christ (UCC). The future church which Pastor Leithart described with moving eloquence in Chapter 3 sounds much like the mild liberalism of the UCC in the 1950s and the 1960s. In line with the title of his book, Rev. Leithart calls for Protestant denominations and churches to “die,” that is, to cease to exist in their present forms in order for new forms to emerge. He writes:

We are called to die to our divisions, to the institutional divisions of denominationalism, in order to become what we will be, the one body of the Son of God (p. 165; emphasis added).

Similar language of death and rebirth as a means to church unity can be found in the UCC’s 1957 “The Preamble to the Basis of Union” which reads:

Affirming our devotion to one God, the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, and our membership in the holy catholic Church, which is greater than any single Church and than all the Churches together;

Believing that denominations exist not for themselves but as parts of that Church, within which each denomination is to live and labor and, if need be, die; and

Confronting the divisions and hostilities of our world, and hearing with a deepened sense of responsibility the prayer of our Lord “that they all may be one” . . . . (Emphasis added.)

All that Rev. Leithart has done in End of Protestantism is to update the ecumenical vision of the 1950s that gave birth to the UCC. So what’s new?

The Challenge of Liberal Theology

Peter Leithart’s vision of the future church is one where church unity takes priority over doctrinal specificity. Love and inclusion takes priority over exclusivist fundamentalism. Theologically, the future church will embrace the rich multiplicity of confessions but with no one confession binding on all.

Confessions, however, will cease to serve as wedges to pry one set of Christians from another. Confessions will be used for edification rather than as a set of shibboleths for excluding those who mispronounce (pp. 27-28; emphasis added).

There is a subtle disparaging tone here in Pastor Leithart’s understanding of how creeds function to protect the Church against heresy. He decries what he calls “shibboleths,” but there have been instances when so-called minor differences have had tremendous consequences. Historically, the Nicene Creed functioned to protect the Church from heresy. While the Nicene Creed was being formulated, there was a debate over whether the Son was homoousios (same Being) with the Father or homoiousios (similar being) with the Father. The difference in just one letter – one iota – meant the difference between affirming Jesus’ divinity or denying it. (See Peter Brown’s article about the iota of difference.) Leithart’s inclusive approach to creeds, by relativizing the authority of the creeds, opens the door to heresy.

A striking similarity can be seen in the way Pastor Leithart and the UCC both sought to read Scripture in the context of the historic creeds. Leithart writes:

Confessions and creeds will remain in play. Churches will unite around the early creeds and will continue to use the treasures of the great confessions of the Reformation, of Trent and the Catholic Catechism, and of the hundreds of creeds and confessions that the global South will produce between now and then (p. 27).

The UCC’s Basis of Union “Section II. Faith” shows a similar inclusive approach:

The faith which unites us and to which we bear witness is that faith in God which the Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments set forth, which the ancient Church expressed in the ecumenical creeds, to which our own spiritual fathers gave utterance in the evangelical confessions of the Reformation, and which we are in duty bound to express in the words of our time as God Himself gives us light. In all our expressions of that faith we seek to preserve unity of heart and spirit with those who have gone before us as well as those who now labor with us (emphases added).

Gabriel Fackre, one of the UCC’s leading theologians, described the UCC’s approach of using creeds to interpret Scripture in a similar way:

As the scriptures are the source of our understanding of Christ, the historic ecumenical and confessional tradition is a key resource in construing its meaning (p. 141; italics in original).

For those who grew up in the provincial sub-culture of Evangelicalism all this might sound daring but for those who grew up in mainline Protestantism this is familiar territory. Within a matter of a few decades the UCC’s inclusive ecumenism degenerated into radical liberalism. For those of us who had to struggle against UCC’s tragic apostasy from historic Christianity Pastor Leithart’s confessional eclecticism strikes us as naive.

Many Evangelicals are unaware of how insulated they are. They hold in high esteem teachers and pastors for their “unique” and “brilliant” insights into Scripture not knowing that much has been borrowed from others. What seem to be bold and innovative teachings are often drawn from one of the early Church Fathers or, worse yet, a revived heresy. This is why knowledge of church history is so important for sound theology.

One of the flaws of the UCC has been its susceptibility to theological liberalism. When my former home church voted to withdraw from the UCC, I was struck by two things: (1) how so many liberals were enraged at my home church’s decision to exercise congregational autonomy in order to hold to what the Bible teaches and (2) the casual disregard the liberals had towards the doctrinal issues that prompted my former home church to withdraw. Surprisingly, Peter Leithart devoted very little attention to the threat of Liberalism (p. 78, 178). This makes me suspect that Pastor Leithart seriously underestimates the danger of liberal theology. From my time in the UCC, I can say I’ve experienced Peter Leithart’s “reformed Catholic church.” It is like a delightful and colorful Indian summer before the cold grey and grim winter sets in.

I have several questions for Pastor Leithart:

- When you described the future ‘reformed Catholic church,’ are you not reiterating the mildly liberal United Church of Christ of the 1950s and 1960s?

- And given the UCC’s later apostasy, what safeguards will your ‘reformed Catholic church’ have to ensure it remains in historic orthodoxy?

Post-Evangelical Eclecticism

The Evangelical subculture in many ways is a closed off, provincial religious ghetto. Most who grow up within this bubble are all but completely unaware of this rich heritage to be found in the two thousand years of church history. When they do discover this bigger world many become enthusiastically inclusive and eclectic in their theology and practices giving rise to what many have dubbed “post-Evangelicalism.” This post-Evangelical shift can lead to a quest for church unity. Peter Leithart’s ecumenical vision reflects this optimistic post-Evangelical eclecticism.

Former Lutherans will discover fresh insights in the writings of former Mennonites and Calvinists; former Baptists will study encyclicals from Rome with appreciation; former Methodists will deepen their insights into the liturgy by studying Eastern Christian writers. . . . . Origen and Augustine and Aquinas and Luther and Barth will be remembered and honored (p. 27)

What Pastor Leithart writes above is nothing new. In my early days, I felt stifled by the literature of popular Evangelicalism, so I was delighted to discover the theological richness of the Heidelberg Catechism and Calvin’s Institutes. Later, I began to explore Roman Catholicism, reading John Paul II’s encyclicals, the documents of the Second Vatican Council, Francis of Assisi, Theresa of Avila, John of the Cross, and GK Chesterton. To balance things out, I also read up on liberation theology: Gustavo Gutierrez and Leonardo Boff; and contemporary Catholic spirituality writers like Thomas Merton and Henri Nouwen. While I was reading up on covenant theology and Mercersburg Theology, I was also trying to keep up with the Charismatic Renewal. At first, all of this reading was exciting, but after awhile it became tiring. I was like a tourist constantly on the road, visiting new and exotic locations. I never really settled down for long, and when I did come back to my Protestant home, I found that the neighborhood had changed quite a bit. I felt at home with the people of my home church but did not really feel at home theologically. Many American Christians today likewise drift from one new and grand theological insight to the next, religious nomads looking for greener pastures.

Our theological systems are like maps. They purport to tell us where we came from, where we are at present, and they guide us to where we wish to go – to our destination. Not all maps are accurate. As a matter of fact, bad maps will take us into great danger. One could collect maps as a hobby, but when on the road, one needs to commit to one good map to reach one’s destination. Constantly switching maps does no good if one is lost and trying to find the way home. Post-Evangelicals who enthusiastically read across religious traditions are like avid map collectors. They may enjoy seeing the wide world out there but sooner or later they will have to decide where their spiritual home is. Eventually, after reading extensively across traditions, I found myself drawn to the ancient wisdom of the early Church Fathers which helped me discover the historic Orthodox Church.

Jesus’ Prayer for Unity – An Exegetical History

One key premise of Rev. Leithart’s book is that God will fulfill Jesus’ prayer in John 17 for a future unified Church (pp. 13, 115, esp. 173). We read in John 17:

My prayer is not for them alone. I pray also for those who will believe in me through their message, that all of them may be one, Father, just as you are in me and I am in you. May they also be in us so that the world may believe that you have sent me. I have given them the glory that you gave me, that they may be one as we are one: I in them and you in me. May they be brought to complete unity to let the world know that you sent me and have loved them even as you have loved me. (John 17:20-23, NIV; emphasis added)

Leithart made John 17 foundational to his quest for church unity:

We can know that God will keep his promise to make his people one as he is one with his Son. Somehow, someday, reunion will happen, because the Father gave his Son to make it happen (p. 26).

To achieve anything resembling this vision, every church will have to die, often to good things, often to some of the things they hold most dear. Protestant churches will have to become more catholic, and Catholic and Orthodox churches will have to become more biblical. We will all have to die in order to follow the Lord Jesus who prays that we all may be one (p. 36).

But does Jesus’ prayer for unity in John 17 apply to Protestantism’s divisions? To answer this question, we need to look at how historically the early Church Fathers interpreted this passage.

Ambrose of Milan (c. 339-397) understood this reference to unity as an affirmation of Jesus’ divinity. In Of the Christian Faith Book 4 Chapter 3 §34 he writes:

But who can with a good conscience deny the one Godhead of the Father and the Son, when our Lord, to complete His teaching for His disciples, said: “That they may be one, even as we also are one.” The record stands for witness to the Faith, though Arians turn it aside to suit their heresy; for, inasmuch as they cannot deny the Unity so often spoken of, they endeavour to diminish it, in order that the Unity of Godhead subsisting between the Father and the Son may seem to be such as is unity of devotion and faith amongst men themselves continually of nature makes unity thereof. (NPNF Vol. X, p. 266, cf. p. 227)

Augustine of Hippo (354-430) understood Jesus’ reference to his unity with the Father as an affirmation of his role as divine Mediator. In his homilies on the Gospel of John Tractate 110 §4 Augustine notes:

And then He added: “I in them, and Thou in me, that they may be made perfect in one.” Here He briefly intimated Himself as the Mediator between God and men.

But in adding, “That they may be perfect in one,” He showed that the reconciliation, which is effected by the Mediator, is carried to the very length of bringing us to the enjoyment of that perfect blessedness, which is thenceforth incapable of further addition. (Homilies on the Gospel of John; NPNF Series I, Vol. 7, §4; p. 410)

In The Trinity Augustine understood John 17:21 to be an affirmation of Jesus’ divinity and his office as mediator. He writes:

This is what he means when he says that they may be one as we are one (Jn 17:22)—that just as Father and Son are one not only by equality of substance but also by identity of will, so these men, for whom the Son is mediator with God, might be one not only by being, of the same nature, but also by being bound in the fellowship of the same love. Finally, he shows that he is the mediator by whom we are reconciled to God, when he says, I in them and you in me, that they may be perfected into one (Jn 17:23). (The Trinity Book 4, Chapter 2 §12; p. 161; Transl. Edmund Hill; italics in original, bold added; NewAdvent.org On the Holy Trinity Book 4 chapter 9)

The context for mediation here is that unity between God and sinful humanity, not a unity among rival denominations.

Cyprian of Carthage (c. 200/210-258) received a letter (date 256) from Firmilian, the Bishop of Caesarea in Cappadocia, which contains a reference to John 17:21. Firmilian used the passage to affirm the Church’s unity in the face of geographic separation. He also understood John 17 as referring to the Christian’s union with God.

And this also which we now observe in you, that you who are separated from us by the most extensive regions, approve yourselves to be, nevertheless joined with us in mind and spirit. All which arises from the divine unity. For even as the Lord who dwells in us is one and the same, He everywhere joins and couples His own people in the bond of unity, whence their sound has gone out into the whole earth, who are sent by the Lord swiftly running in the spirit of unity; as, on the other hand, it is of no advantage that some are very near and joined together bodily, if in spirit and mind they differ, since souls cannot at all be united which divide themselves from God’s unity. “For, lo,” it says, “they that are far from Thee shall perish.” But such shall undergo judgment of God according to their desert, as depart from His words who prays to the Father for unity, and says, “Father, grant that, as Thou and I are one, so they also may be one in us.” (Epistle LXXIV §3, NPNF Series 2 Vol. V, pp. 390-391; emphases added)

The controversial Alexandrian theologian Origen (c. 185-c. 254) interpreted John 17:21 in light of Neo-Platonist philosophy. In De Principiis he describes how the end will be like the beginning. He notes that where the Fall consists of humanity and creation lapsing into complexity and diversity, the end will consist of the restoration to unity promised in John 17:21 (ANF Vol. IV, De Principiis Book I, Ch. 6 §2; pp. 260-261).

John Chrysostom (c. 344/354-407) notes in Homily 82 in the series on John’s Gospel that verse 21 refers to concord among the Christians and that verse 23 means that peace has greater ability to persuade men than miracles (NPNF Series 2 Vol. XIV, p. 304; New Advent Homily 82).

To sum up, a review of early Christian writings fails to show anyone interpreting Jesus’ prayer in John 17:20-23 in a manner similar to Rev. Leithart’s. This lacuna – the failure to consider other possible readings of John 17 – raises significant questions about the validity of Pastor Leithart’s exegesis. The absence of patristic precedence suggests that Leithart’s ecumenical reading of John 17:20-23 is a novelty. This in turn suggests that he has wrongly applied the Johannine passage to the Protestant predicament of division and denominationalism. The dubiety of Leithart’s exegesis turns his future-oriented ecumenism from inevitable to improbable. If the biblical basis for Rev. Leithart’s evolutionary ecumenism is flawed, then it needs to be revised or even discarded for another approach to church unity.

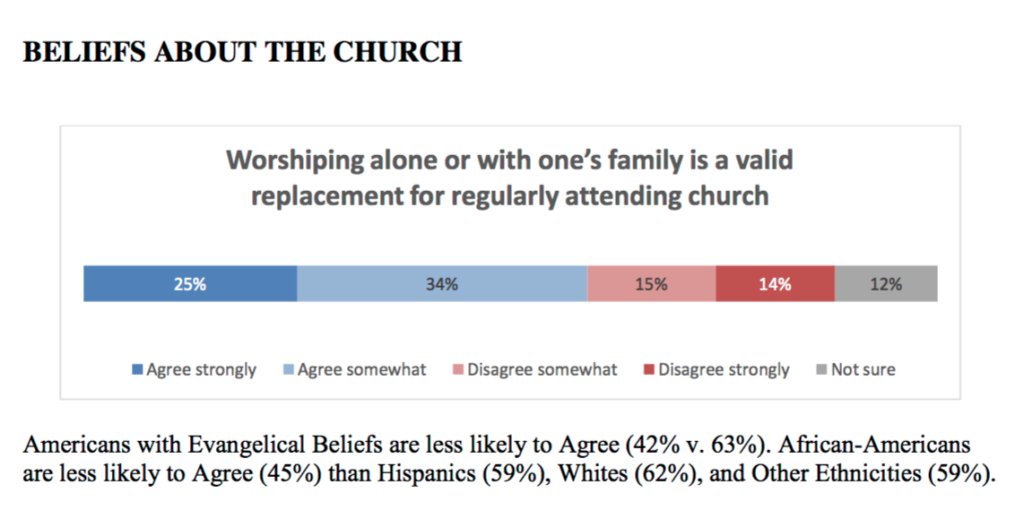

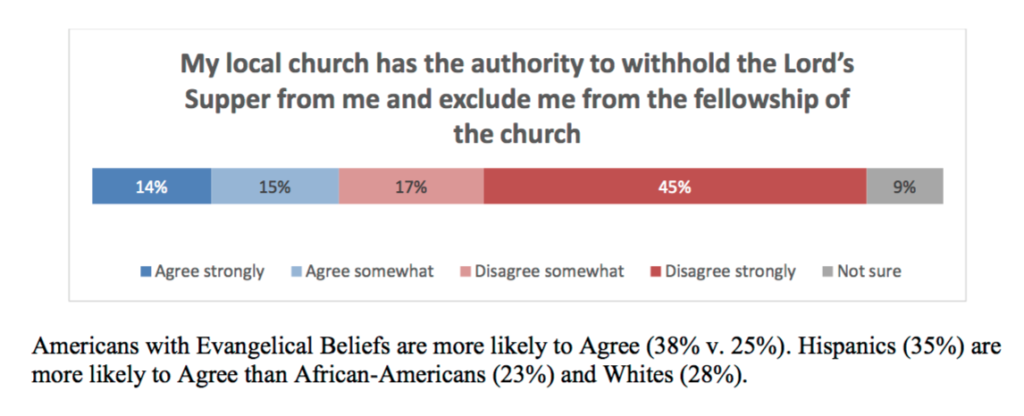

Is Closed Communion Divisive?

Pastor Leithart laments the “divisiveness” of closed communion (p. 170), but he should take into consideration the benefits of closed communion. Historically, closed communion, by protecting the Church against heresies, upheld the unity of the Church. Interestingly, Protestant churches have overwhelmingly (until recently) taken their cue from Calvin, Luther, and other Reformers who practiced closed communion. It was not until the 1970s that open communion became widely accepted in Protestant circles. In other words, Leithart’s call for open communion is a novelty at odds with historic Protestantism and ancient Christianity.

Receiving Communion in the Orthodox Church is a sign of one’s sharing the same faith with the Ancient Church as well as with fellow Orthodox believers today. What makes this possible is that every local Eucharistic celebration is carried out under the bishop who is part of the chain of succession going back to the Apostles. For example, the local Greek Orthodox parish through its bishop has a direct historical link to John Chrysostom and the Ecumenical Councils. The local Antiochian Orthodox parish through its bishop has a direct historical connection to John of Damascus and Ignatius of Antioch. This historic connection is something no Protestant church can claim due to the schism underlying the Reformation.

Pastor Leithart is more than welcome to partake of Eucharist at an Orthodox church providing he is willing to accept Apostolic Tradition and come under the teaching authority of the Orthodox bishops, the successors to the Apostles. But if he wishes to hold on to the doctrinal innovations of the Protestant Reformation of the 1500s then he should accept the fact that he has chosen to walk in a different tradition. Protestantism and Orthodoxy are not theologically compatible. Where many Protestants view theology as negotiable, for the Orthodox Apostolic Tradition is a treasure to be safeguarded for future generations until the Second Coming.

Leithart’s Questions for Inquirers

The solutions put forward by Pastor Leithart seem to be intended for the divisions within Protestantism. He does not devote much attention to Protestantism’s differences with Roman Catholicism and Orthodoxy. However, he looks askance at Protestants who are interested in Orthodoxy. To Protestants contemplating conversion to Orthodoxy, Leithart posed two questions:

- “What are you saying about your past Christian experience by moving to Rome or Constantinople?” and

- “Are you willing to start eating at a eucharistic table where your Protestant friends are no longer welcome?” (p. 170)

My answers to Rev. Leithart’s questions are as follow:

- With respect to the first question, I would say: “I am deeply indebted to Protestantism for introducing me to the Bible. I am looking forward to joining the Church that gave us the Bible.”

- With respect to the second question, I would say: “To be Protestant is to be cut off from eucharistic fellowship with the Ancient Church. It is regrettable that Reformers have rejected certain key doctrines that were affirmed by the Seven Ecumenical Councils. Your proposed solution is intrinsically schismatic, even if that is not the intent.”

What Defines Orthodoxy

Pastor Leithart is under the mistaken impression that Orthodoxy defines itself on the basis of differences with Roman Catholicism and Protestantism (p. 38). The starting point for his paradigm of church history is the Church being broken into many pieces – while we all have different pieces of the puzzle; no one has the whole picture. This forms the basis for his evolutionary approach to ecumenism which assumes that the various parties should come together and negotiate theology. Implicit to this view is theological relativism; in this paradigm there is no doctrinal orthodoxy that holds across time and space.

. . . all disputants must acknowledge that we see through a glass darkly, now only in part. We should all be ready to be corrected by brothers and sisters, whatever tradition they inhabit. We should all do theology with a prayer for brighter, more comprehensive light (p. 173).

Orthodoxy, on the other hand, has a different starting point. What defines Orthodoxy is fidelity to Apostolic Tradition. This is the Tradition of the Apostle spoken of repeatedly within Scripture (2 Thessalonians 2:15, 2 Timothy 1:13-14). This is THE Faith once and for all entrusted to the saints (Jude 3). The phrase “once and for all” means a one-time only giving of Apostolic Tradition, not a progressive, gradually evolving of the Christian Faith. Athanasius the Great summarized the importance of Holy Tradition for Orthodox identity:

But, beyond these sayings, let us look at the very tradition, teaching, and faith of the Catholic Church from the beginning, which the Lord gave, the Apostles preached, and the Fathers kept. Upon this the Church is founded, and he who should fall away from it would not be a Christian, and should no longer be so called. (Epistle 1 to Serapion §28)

Orthodoxy insists on keeping the Apostolic Faith intact – unlike Roman Catholicism which has added to Holy Tradition and Protestantism which has rejected parts of Holy Tradition. This can be ascertained through a comparison of the Orthodox Church today with the Ancient Church. Leithart’s evolutionary approach is radically at odds with Orthodoxy’s two thousand years of safeguarding Apostolic Tradition.

To readers who find Pastor Leithart’s vision of a reunified church that includes Orthodoxy appealing, I want to say in all charity and truthfulness: “That’s not going to happen. We’re Orthodox; we don’t change.” This means that those who wish to remain Protestant should realize this means walking on a separate path from Orthodoxy. We can have friendly relations, but we will not share in the Eucharist. I am not opposed to what Leithart referred to as “strategic alliances” (p. 64). This is very much needed as we move into a post-Christian American culture.

My Assessment

Despite his commendable intentions, Peter Leithart’s End of Protestantism suffers from several serious flaws.

First, Leithart’s evolutionary approach to church history creates a division between present day Protestantism and the Ancient Church. The notion of an embryonic Apostolic Faith is nowhere to be found in Scripture or in church history. The Faith, once and for all delivered by the Apostles to the Church, was never assumed to be an infant or immature Faith that continually morphs and evolves throughout history. They understood it to be a mature Faith from the start. Many Protestants are unaware that their doctrines and worship would bar them from receiving Communion in the Ancient Church.

Second, Leithart’s book provides a dubious Protestant solution to a Protestant problem. His refusal to even consider relinquishing Protestant beliefs serves only to reinforce the schism with the Ancient Church. For example, none of the Church Fathers taught the Protestant doctrine of sola scriptura. While the early Church Fathers did affirm the authority of Scripture, they taught Scripture IN Tradition. With sola scriptura the Protestant Reformers introduced the novel notion of Scripture OVER Tradition. By jettisoning Holy Tradition, sola scripura opened the door to Protestantism’s hermeneutical chaos and the unprecedented proliferation of denominations. It is only with the repudiation of sola scriptura and the return to Apostolic Tradition that Protestantism can find healing for its divisions. Protestants longing for the one holy catholic and apostolic Church need to break out of the Protestant paradigm of sola scriptura and embrace the paradigm of Apostolic Tradition.

Third, Leithart’s proposed Reformational Catholicism sounds very much like a repeat of the ecumenical approach taken by the United Church of Christ which has since succumbed to theological liberalism. Church history contains many valuable lessons. It behooves Pastor Leithart and readers of his book to heed the warning from the tragedy of the UCC lest they repeat the UCC’s ecumenical disaster.

Fourth, the premise underlying Leithart’s ecumenical vision – John 17:21-23, is based on a novel reading at odds with historic exegesis. Because Protestants revere Scripture as the divinely inspired Word of God, they value the right interpretation of Scripture. The questionable exegesis underlying Pastor Leithart’s ecumenical vision should give thoughtful Protestants pause.

Fifth, with respect to Protestantism’s schism with Orthodoxy Rev. Leithart’s greatly underestimates how his Protestantism sabotages any attempt to reconcile the two traditions. Protestants need to realize that they are walking in a tradition separated from Ancient Christianity. In 1672, the Orthodox Church in the Confession of Dositheus formally condemned Reformed theology. The formal conciliar nature of this rejection of Protestantism is something ecumenists like Leithart cannot avoid. Peter Leithart’s optimistic future oriented ecumenism holds that the two paths will one day meet up but this review has raised issues that call this into question. Leithart has not taken seriously the difficulty of merging Protestantism with Orthodoxy.

Indeed, Protestants must come to terms with their duplicity toward the early Church, particularly the Church Fathers and Ecumenical Councils. One cannot at one and the same time mine gems of theological truth and wisdom from the Church Fathers then later scorn and vilify them as idolaters or immature theologians.

As a theological map Peter Leithart’s The End of Protestantism is flawed. It will likely take its users into dangerous territory and cause them to waste valuable time that could be used more productively. There are two alternative paths to the future for the reader. One is to exclude Orthodoxy from Leithart’s ecumenical vision. This is the path if one wishes to hold on to one’s Protestant identity. The other is to be willing to measure Protestantism against the Ancient Church and being open to making changes in light of Ancient Christianity. In addition to the example of Peter Gillquist’s Becoming Orthodox, there is the more recent example of Joseph Gleason in the article “A Calvinist Anglican Converts to Orthodoxy.”

A Thought Experiment

Imagine that Ignatius of Antioch and Irenaeus of Lyons appear at Pastor Leithart’s church in Birmingham, Alabama, one Sunday morning. Ignatius was the third bishop of Antioch, Apostle Paul’s home church (see Acts 13:1-3). He authored several letters just before his martyrdom around 98/117. Irenaeus was the bishop of Lyons, a city on the western edge of the Roman Empire. He was the disciple of Polycarp, who was the disciple of Apostle John, and wrote Against Heresies prior to his martyrdom circa 195. Both men lived in the second century shortly after the Apostles had passed on and were known for their zeal in defending the Christian Faith. What would they say to Leithart over coffee after worship?

Likely, Ignatius’ question would be, “Who is your bishop?” As a good Calvinist, Leithart’s answer would be: “We don’t have bishops. We’re Reformed Presbyterians.” Ignatius’ follow-up question would likely be: “But you do know that without a bishop’s approval you don’t have a valid Eucharist? You would know this if you read my letter to the Smyrnaeans.” Irenaeus would then chime in, “Reformed Protestants? I never heard of these words. Is this part of Tradition received from the Apostles? I was talking with one of your parishioners and he told me that the Protestant Reformation began in the 1500s!”

Let us say that a little later bishops Ignatius and Irenaeus were to sit down for lunch with the local Orthodox priest with Pastor Leithart joining them. In the course of the meal Ignatius would ask the Orthodox priest: “Who is your bishop?” The priest would quickly answer: “His Grace Bishop Alexander of the Diocese of the South of the Orthodox Church in America.” Irenaeus would follow up with, “Do you teach the Tradition of the Apostles?” The priest would answer: “Our church home page has this statement of purpose: ‘The community is committed to keeping the Faith as transmitted by the Apostles to the first Fathers of the Church and preserved in the Holy Orthodox Church.’” At some point Pastor Leithart must reckon with the reality. First, the saints of old would find the innovations of Protestantism strange and at odds with Apostolic Tradition. Second, they would recognize the historic Tradition of the Apostles preserved and guarded in the local Orthodox parish. A sobering reality indeed for Protestants.

Protestantism’s End

We are thankful for Protestant men like Pastor Leithart who seriously seek Church unity and wonder if the title of his book tells us more than he intended? If Protestants are truly sincere about uniting with Orthodoxy, they would need to embrace the Orthodox Church in all its fullness and historicity. This, to play on the title of Leithart’s book, would mean the end of Protestantism. It can be done. Peter Gillquist’s Becoming Orthodox tells how a group of Evangelicals transitioned from Protestantism to Orthodoxy. The transition was not easy. Returning to the Faith of the Ancient Church required their relinquishing certain Protestant beliefs, but in 1987 some 2000 Evangelicals were received into the Orthodox Church. Readers who wish to know more about what is involved in transitioning from Protestantism to Orthodox will find the article “Crossing the Bosphorus” helpful on the theological and practical levels.

Robert Arakaki

References

Robert Arakaki. 2012. “Unintended Schism: A Response to Peter Leithart’s ‘Too Catholic to be Catholic.’” OrthodoxBridge (12 June).

Robert Arakaki. 2013. “Crossing the Bosphorus.” OrthodoxBridge (15 January).

Athanasius the Great. 1951. The Letters of Saint Athanasius Concerning the Holy Spirit to Bishop Serapion. Trans. and ed., C.R.B. Shapland. Uploaded by Mark Walley 2014.

Augustine. 1991. The Trinity. Translator, Edmund Hill, OP. New City Press.

Peter Brown. 2014. “The Homoousios Controversy and Semi-Arianism.” Jesus Christ God, Man and Savior Week Six: God the Son at Nicea and Constantinople. (Version 7 updated 5 October).

Fr. Stephen Andrew Damick. 2013. “‘A Premodern Sacramental Eclectic?’: Evangelicals Reaching for Tradition.” OrthodoxyAndHeterodoxy (25 June).

Gabriel Fackre. 1990. “Christian Doctrine in the United Church of Christ.” In Theology and Identity: Traditions, Movements, and Polity in the United Church of Christ. Edited by Daniel L. Johnson and Charles Hambrick-Stowe. Pilgrim Press.

Peter Gillquist. 2010. Becoming Orthodox. Conciliar Press, 3rd edition.

Joseph Gleason. 2013. “A Calvinist Anglican Converts to Orthodoxy.” JourneyToOrthodoxy (24 October).

Peter Leithart. 2016. End of Protestantism: Pursuing Unity in a Fragmented Church. Brazos Press (a division of Baker Publishing Group).

Peter Leithart. 2012. “Too Catholic to be Catholic.” First Things (21 May).

John Williamson Nevin. 1978. “Early Christianity.” Catholic and Reformed, pp. 177-310. Editors, Charles Yrigoyen and George Bricker. The Pickwick Press.

Andrew Tooley. 2007. “Emerging Church: Evangelical or Post-Evangelical Pioneer?” Catalyst ( 1 November).

United Church of Christ. “Basis of Union.”

Brian Zahnd. 2013. “A Premodern Sacramental Eclectic.” BrianZahnd.com (24 June)

See Also

David George Moore. 2016. “End of Protestantism (a review of Peter Leithart).” Jesus Creed (22 October).

Kris Song. 2016. “Is This the ‘End of Protestantism?’ A Review of Peter Leithart’s Latest Book on Church Unity.” The Two Cities (27 October).

Fred Sanders. 2016. “Does Protestantism Need to Die?” Christianity Today (21 October).

Douglas Wilson. 2016. “The Purported End of Protestantism.” Blog and Mablog (2 November).

Recent Comments