A response to Anastasiya Gutnik’s comment 24 June 2016:

From Anastasiya:

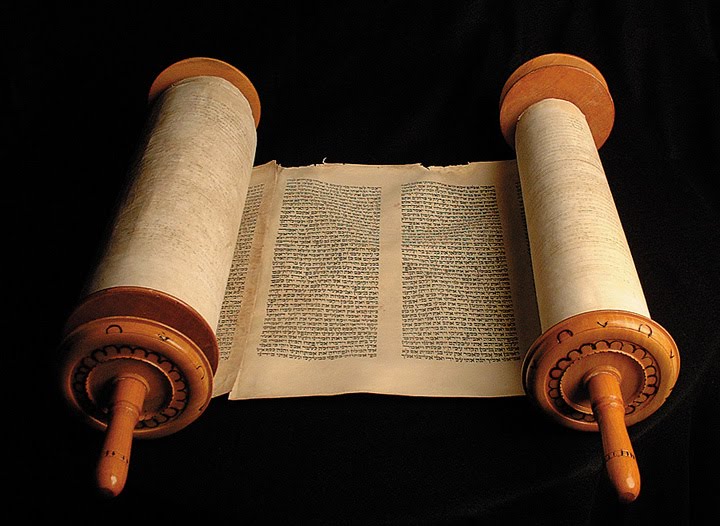

What do you think of Josiah? In his time the worship of God was corrupt. So much so that the law was literally a musty, dusty old book found hidden away in the temple. Upon rediscovering the law Josiah launched a reformation destroying the idols and the altars upon which idolatry was practiced. Does this mean there were none of God’s people left? But as Paul writes about the time of Elijah “I have reserved 7000 who have not bowed to Baal. So there is a remnant according to election of grace.” How is his any different than the Protestant Reformation? What are your thoughts on the Apostle Paul warning that wolves would come and tear up the flock and that apostasy would happen after his departure? And what are you thoughts on his statement regarding the times of Elijah?

The church is composed of individuals “one of a city, two of a family” as Jeremiah writes. So what do you have against individual believers receiving the Holy Spirit? In the Acts we see individuals corporately receiving the Spirit (such as Cornelius and his house). And what Protestant ever said this is done apart from the Church? Article 28 of the Belgic Confession explicitly says of the Church that “out of it is no salvation.” Even today in the apostate and corrupt churches like Hillsong they still recognize the importance of corporate worship and belonging to a community of believers.

MyResponse

Whoa! All these questions! I feel like I’m being interrogated by a prosecuting attorney. What say you that we have a friendly dialogue between the two of us?

I appreciate your vigorous interaction with the OrthodoxBridge. We may not see eye-to-eye on some issues, but we share common ground in our respect for Scripture. I will explain my positions using the Bible.

Protestantism in the Old Testament?

Your listing of Old Testament passages seems to rest on the premise that the Protestant Reformation has parallels in the Old Testament, thereby providing biblical justification for the Reformation. This entails the hermeneutical strategy of reading the history of Christianity, especially the Protestant Reformation, onto the Old Testament text. Getting the types and parallels of Christ and Israel right is what the Jews of Jesus’ time were so poor and weak at. They were often dead wrong. This means that using the hermeneutics of history approach calls for caution. Orthodoxy approaches church history through the lens of the unique promise of Pentecost — Christ’s Upper Room promise that he would send the Holy Spirit to guide the Church (John 14-16), and Christ’s promise that powers of hell would never prevail over the Church (Matthew 16:17-18). Orthodoxy sees church history as one continuous, unbroken narrative from the book of Acts to the present day. We view world history as the history of the one Church through which God’s power and wisdom unfold bringing about the salvation of the cosmos (Ephesians 1:18-22).

The Apostle Paul’s prediction of the coming of “savage wolves” attacking the flock (Acts 20:29-30) parallels Apostle John’s counsel about heretics who denied that Jesus had come in the flesh (1 John 2:18-23). The early Church had to deal with early heresies like Gnosticism, Arianism, and Manichaeism. It survived these heresies, and in time Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire. It is difficult to see there being a universal apostasy as you seem to have implied.

If one wants to find a possible parallel for Protestantism, I suggest it would be the northern tribes’ revolt against Rehoboam (1 Kings 12:12-17). What made that schism so tragic was not so much the rejection of the Jerusalem monarchy but Jeroboam’s creation of rival worship centers in Bethel and Dan, and the installation of a new rival priesthood (1 Kings 12:26-33). These innovations made the schismatic Israelites susceptible to syncretistic borrowing of religious practices from their neighbors.

In your first paragraph you cited the example of King Josiah (2 Kings 23) reading the Book of the Covenant and cleansing the Temple of pagan idols suggesting it has parallels with the Reformation. What he did was to follow the covenant obligations imposed on the king in Deuteronomy 17:14-20. In no way did King Josiah introduce new doctrines or worship practices. This has been one of my primary critiques of the Protestant Reformers. They rightly reacted against many of the abuses and innovations of Medieval Catholicism. They sought to return to the original Church, not through the Pentecost paradigm — the Holy Spirit working without break through the Church for the past 1500 years, but rather through the novel method of sola scriptura. This gave rise to novel doctrines not taught by the early Church Fathers or were condemned by early Councils. Furthermore, it gave rise to a plethora of Protestant denominations with conflicting interpretations of the Bible. The Protestant rejection of the episcopacy (priestly leadership) and their rejection of the Real Presence in the Eucharist (right worship) as understood by the early Church bears an uncanny parallel with Jehoboam’s innovations. This is something that should give thoughtful Protestants pause.

You mentioned the Apostle Paul’s quoting 1 Kings 18 about the faithful remnant of 7000 who refused to bow down to Baal (Romans 11:4). The important point to keep in mind is that Romans 11 is not about the Protestant Reformation of the 1500s, but about the perplexing situation in Paul’s time. The Messiah had come and instead of welcoming Jesus as the promised Messiah, Israel chose to reject and murder God’s Chosen One. This created a conundrum: Either Jesus was not the promised Messiah or the Jews were no longer God’s people. These questions were likely on the minds of Paul and his fellow Jewish Christians. This question quite possibly contributed to the tensions between Jews and Gentiles which seem to lurk in the background of Paul’s letter to the Romans. Did Paul’s conversion to Christ require the renunciation of his ethnic heritage and religious roots? Was Israel no longer Israel? Romans 11 is Paul’s solution to the conundrum. In it he explains the relationship between the Israel of the Old Testament and the New Israel, the Church. In this context it becomes clear that when Paul alludes to the faithful remnant of the 7,000, he has in mind himself, his fellow Apostles, and Jewish Christians.

To claim the Protestant Reformers comprise the faithful remnant of 7,000 mentioned by Paul involves reading Protestant church history into the Bible, a very dubious proposition. This reading of Scripture cannot be asserted; it must be proven. For several decades now, Anglican Bishop and bible scholar, NT Wright, has been pointing out this common Protestant flaw of reading the Reformation back into Scripture. Lowell Handy’s “The Good, Bad, Insignificant, Indispensable King Josiah” (2005) traces the place of King Josiah in church history. Among the early Church Fathers and into the Middle Ages, Josiah occupied a minor role in biblical studies (Handy 2005:41). He acquired prominence in the 1500s among the Protestant Reformers who saw in Josiah a model of a reforming king and in the 1800s among Protestant bible scholars who saw the “Book of the Covenant” read by Josiah as evidence for a revised understanding of Old Testament formation. In other words, the prominence given to Josiah is peculiar to Protestantism and does not reflect the broader Christian exegetical tradition. This retroactive approach of reading Protestant history into the Bible is highly speculative and self-serving.

The Church — Individuals versus Corporate Body

In your second paragraph you cited Jeremiah 3:14 — one from a city and two from a family — to justify the idea of the church as an aggregate of individuals. This is a bit of a stretch. Where is this interpretation found in church history? Some of the more extreme Protestant groups believe that all one needs to comprise a church is a group of like-minded believers who gather to hear sermons about the Bible. But that is like saying gathering a group of kids and giving them a ball makes them a team! They need to agree that they are a team, playing the same sport by the same rule, and under a team leader. A more pertinent passage for explaining the individual Christian’s relation to the corporate body, the Church, would be 1 Corinthians 12:12-13:

The body is a unit, though it is made up of many parts; and though all its parts are many, they form one body. So it is with Christ. For we were all baptized by one Spirit into one body—whether Jews or Greeks, slave or free—and we were all given the one Spirit to drink.

And then, there’s 1 Corinthians 12:17:

Now you are the body of Christ and each of you is a part of it.

The Amplified Bible translates 1 Corinthians 12:27 it this way:

Now you [collectively] are Christ’s body, and individually [you are] members of it [each with his own special purpose and function].

The key point here is that we become part of the Church through the sacrament of baptism. One does not join the Church as one is received by the Church. Furthermore, Paul understood the Church to possess an internal structure, an ordering of ranks. In 1 Corinthians 12:27-28, Paul lists the orders of church ministries: apostles, prophets, teachers, and workers of miracles. In Ephesians 4:11, he gives a slightly different ordering: apostles, prophets, evangelists, pastors and teachers. From these passages we learn that the Church is not an aggregate of independent individuals, but rather a corporate body of interrelated members. There is no need to grasp at obscure or dubious Old Testament passages for our doctrine of the Church when there are New Testament passages that give us greater clarity on the question before us. As a matter of fact, the Reformed tradition’s teaching about the Church as a covenant community speaks against the individualistic approach that you seem to favor.

In no way am I opposed to the idea of individuals receiving the Holy Spirit. The real issue is whether one can receive the Holy Spirit independently of the visible Church. The main difference is that Protestants deny that we receive the Holy Spirit through the sacrament of the Church (chrismation). However, they need to take into account the fact that the sacrament of chrismation was very much a part of early Christian initiation. Cyril, the patriarch of Jerusalem in the 300s, described the sacrament of chrismation in which the newly baptized is anointed on the forehead, the ears, the nostrils, and the breast. (Catechetical Lecture 21.4) This remains the practice of the Orthodox Church to the present. The point here is that just as baptism is a sacrament administered by the Church through its ordained clergy, so the reception of the Holy Spirit takes place via the sacrament of chrismation which immediately follows baptism.

The issue of the “baptism in the Holy Spirit” has been an especially divisive one for Protestants. Baptists and many Evangelicals equate the baptism in the Holy Spirit with the “born again” experience. Pentecostals and many charismatics identify the baptism in the Holy Spirit as an experience distinct from the born again experience and signified by the gift of tongues. It’s not clear to me what the Reformed tradition’s position of the reception of the Holy Spirit is. I searched through the Belgic Confession, which you cited, and while there were numerous references to the Holy Spirit, there seem to be no specific teaching about the point in time when the Christian receives the Holy Spirit. I then searched through the Heidelberg Catechism, the Westminster Larger Catechism, and the Westminster Confession and was not able to find anything with respect to the reception of the Holy Spirit. Please help me on this. Where does the Reformed tradition stand on the baptism in the Holy Spirit? When does this take place for the Christian? Does it takes place at the time of baptism, the born again experience, or is it an individual experience distinct from baptism?

You cited article 28 of the Belgic Confession. The Belgic Confession‘s affirmation that there is no salvation outside the Church is a reflection of the historic understanding of the Church. The novelty of Protestantism is that it denies that claim to Roman Catholicism. It justifies this denial on the grounds that Roman Catholicism under the papacy has become corrupt, unbiblical, and even apostate. Furthermore, Protestantism lays claim to belonging to the true Church on the grounds that it has the true interpretation of Scripture. This despite the numerous conflicting interpretations of Scripture held by the myriad of denominations! My point is that you can cite Article 28 of the Belgic Confession all you want, but how do you know your church is part of the true Church? Which makes me wonder: “What is your church affiliation? And what leads you to think that your local congregation is part of the true Church?”

In closing, I would like to draw your attention to the fact that Roman Catholicism and Orthodoxy are two quite different religious traditions. They once shared in a common Faith, however, tragically the Bishop of Rome (the Pope) following the Schism of 1054 has moved more and more from the patristic consensus. What Martin Luther and John Calvin were protesting against was a medieval Catholicism quite different from the Church of the first millennium. In that light, I view Protestants as unwitting victims of Rome’s deviation from the early Church Fathers.

I have done my best to respond to your questions. I trust that I have answered them satisfactorily. I look forward to hearing your responses to my questions and to the interesting conversation you and I will have in the near future.

Robert Arakaki

Recent Comments