The doctrine of double predestination is the hallmark of John Calvin and Reformed theology. (#1) It is the belief that just as God predestined his elect to eternal life in Christ, he likewise predestined (reprobated) the rest to hell.

With blunt frankness Calvin wrote:

We call predestination God’s eternal decree, which he compacted with himself what he willed to become of each man. For all are not created in equal condition; rather, eternal life is foreordained for some, eternal damnation for others (Institutes 3.21.5; Calvin 1960:926).

Double predestination was one of Calvin’s more controversial teachings and he wrote extensively to defend this belief. In the final edition of his Institutes, Calvin devoted some eighty pages to defending this doctrine. (#2) Despite its controversial nature, double predestination became the official position of the Reformed churches.

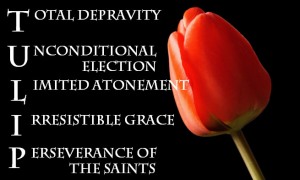

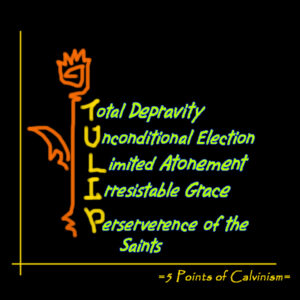

This blog posting will provide an Orthodox critique of Reformed theology. More specifically, it will focus on the doctrinal formula TULIP, because TULIP provides a clear and concise summary of Reformed theology. The acronym is a catchy way of conveying the five major points of the Canons of Dort: T = total depravity, U = unconditional election; L = limited atonement, I = irresistible grace, and P = perseverance of the saints.

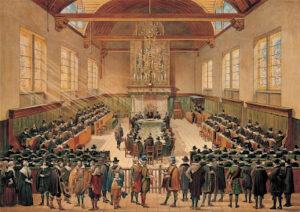

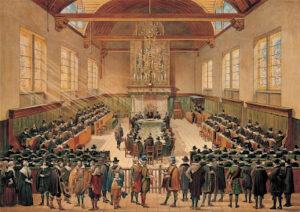

Synod of Dort

The Canons of Dort represent the Dutch Reformed Church’s affirmation of predestination in the face of the Remonstrant movement (popularly known as Arminianism) which attempted in the early 1600s to temper the rigor of predestination by allowing for human free will in salvation. (#3) Although the Canons of Dort form the official confession of the Dutch Reformed Church, its affirmation of predestination parallels that found in other major confessions, e.g., the Westminster Confession, the Second Belgic Confession, and the Heidelberg Catechism. (#4)

Calvinism and Eastern Orthodoxy represent two radically different theological traditions. Orthodoxy has its roots in the early Ecumenical Councils and the Church Fathers, whereas Calvinism emerged as a reaction to medieval Roman Catholicism. Aside from a brief encounter in the early seventeenth century, there has been very little interaction between the two traditions. (#5) This is beginning to change with the growing interest among Evangelicals and mainstream Protestants in Orthodoxy. (#6) This lacuna has often presented a challenge for Protestants in the Reformed tradition who wanted to become Orthodox and Orthodox Christians who want to reach out to their Reformed/Calvinist friends. This is why I created the OrthodoxBridge (see Welcome) and why I am tackling such difficult issues like the doctrine of predestination.

THE ORTHODOX CRITIQUE OF TULIP

This critique will consist of two parts: Part I (this blog posting) will critique the five points of TULIP and Part II (the next blog posting) will discuss Calvinism as an overall theological system.

The critique will proceed along four lines of argument:

(1) Calvinism relies on a faulty reading of Scripture,

(2) it deviates from the historic Christian Faith as defined by the Ecumenical Councils and the Church Fathers,

(3) its understanding of God’s sovereignty leads to the denial of the possibility of love, and

(4) it leads to a defective Christology and a distorted understanding of the Trinity.

T – Total Depravity

Total depravity describes the effect of the Fall of Adam and Eve on humanity. It is an attempt to describe what is otherwise known as “original sin.” Where some theologians believed that man retained some capacity to please God, the Calvinists believe that man was incapable of pleasing God due to the radical effect of the Fall on the totality of human nature. The Scots Confession took the extreme position that the Fall eradicated the divine image from human nature: “By this transgression, generally known as original sin, the image of God was utterly defaced in man, and he and his children became by nature hostile to God, slaves to Satan, and servants to sin.” (The Book of Confession 3.03; italics added) The Swiss Reformer, Heinrich Bullinger, taught that the image of God in Adam was “extinguished” by the Fall (Pelikan 1984:227).

The Canons of Dort asserted the universality and the totality of the Fall; that is, all of humanity was affected by the Fall and every aspect of human existence was corrupted by the Fall.

Therefore all men are conceived in sin, and are by nature children of wrath, incapable of saving good, prone to evil, dead in sin, and in bondage thereto; and without the regenerating grace of the Holy Spirit, they are neither able nor willing to return to God, to reform the depravity of their nature, or to dispose themselves to reformation (Third and Fourth Head: Article 3).

The Canons of Dort (Third and Fourth Head: Paragraph 4) went so far as to reject the possibility the unregenerate can hunger and thirst after righteousness on their own initiative. It insists this spiritual hunger is indicative of spiritual regeneration and only those who have been predestined for salvation will show spiritual hunger.

In taking this stance, the Canons of Dort reflected faithfully Calvin and the other Reformers’ understanding of the Fall. Calvin believed the Fall affected human nature to the point that man was even incapable of faith which is so necessary for salvation. He wrote:

Here I only want to suggest briefly that the whole man is overwhelmed–as by a deluge–from head to foot, so that no part is immune from sin and all that proceeds from him is to be imputed to sin (Institutes 2.1.9, Calvin 1960:253).

Martin Luther held to a similar radical understanding of original sin. At the Heidelberg Disputations, Luther asserted:

‘Free will’ after the fall is nothing but a word, and so long as it does what is within it, it is committing deadly sin (in Kittelson 1986:111; emphasis added).

The Reformed understanding of the Fall derives from Augustine’s interpretation of the story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. Augustine assumed that Adam and Eve were mature adults when they sinned. This assumption led to a more catastrophic understanding of the Fall. However, Augustine’s understanding represented only one reading of Genesis and was not reflective of the patristic consensus. Another reading of Genesis can be found in Irenaeus of Lyons, widely regarded as the leading Church Father of the second century. Irenaeus believed Adam and Eve were not created as fully mature beings, but as infants or children who would grow into perfection (Against the Heretics 4.38.1-2; ANF Vol. 1 p. 521). This foundational assumption leads to radically different theological paradigm. John Hick, in his comparison of Irenaeus’ theodicy against that of Augustine, notes:

Instead of the fall of Adam being presented, as in the Augustinian tradition, as an utterly malignant and catastrophic event, completely disrupting God’s plan, Irenaeus pictures it as something that occurred in the childhood of the race, an understandable lapse due to weakness and immaturity rather than an adult crime full of malice and pregnant with perpetual guilt. And instead of the Augustinian view of life’s trials as a divine punishment for Adam’s sin, Irenaeus sees our world of mingled good and evil as a divinely appointed environment for man’s development towards perfection that represents the fulfilment of God’s good purpose for him (1968:220-221).

Many Calvinists may find Irenaeus’ understanding of the Fall bizarre. This is because Reformed theology, like much of Western Christianity, has become so dependent on Augustine that it has become provincial and isolated in its theology.

One of the key aspects of the doctrine of total depravity is the belief that the Fall deprived humanity of any capacity for free will rendering them incapable of desiring to do good or to believe in God. Yet a study of the early Church shows a broad theological consensus existed that affirmed belief in free will. J.N.D. Kelly in his Early Christian Doctrine notes that the second century Apologists unanimously believed in human free will (1960:166). Justin Martyr wrote:

For the coming into being at first was not in our own power; and in order that we may follow those things which please Him, choosing them by means of the rational faculties He has Himself endowed us with, He both persuades us and leads us to faith (First Apology 10; ANF Vol. I, p. 165).

Irenaeus of Lyons affirmed humanity’s capacity for faith:

Now all such expression demonstrate that man is in his own power with respect to faith (Against the Heretics 4.37.2; ANF Vol. I p. 520).

Another significant witness to free will is Cyril of Jerusalem, Patriarch of Jerusalem in the fourth century. In his famous catechetical lectures, Cyril repeatedly affirmed human free-will (Lectures 2.1-2 and 4.18, 21; NPNF Second Series Vol. VII, pp. 8-9, 23-24). Likewise, Gregory of Nyssa, in his catechetical lectures, taught:

For He who holds sovereignty over the universe permitted something to be subject to our own control, over which each of us alone is master. Now this is the will: a thing that cannot be enslaved, being the power of self-determination (Gregory of Nyssa, The Great Catechism, MPG 47, 77A; in Gabriel 2000:27).

Another patristic witness against total depravity can be found in John of Damascus, an eighth century Church Father famous for his Exposition of the Catholic Faith, the closest thing to a systematic theology in the early Church. John of Damascus explained that God made man a rational being endowed with free-will and as a result of the Fall man’s free-will was corrupted (NPNF Series 2 Vol. IX p. 58-60). Saint John of the Ladder, a sixth century Desert Father, in his spiritual classic, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, wrote:

Of the rational beings created by Him and honoured with the dignity of free-will, some are His friends, others are His true servants, some are worthless, some are completely estranged from God, and others, though feeble creatures, are His opponents (1991:3).

Thus, Calvin’s belief in total depravity was based upon a narrow theological perspective. His failure to draw upon the patristic consensus and his almost exclusive reliance on Augustine resulted in a soteriology peculiar to Protestantism. However great a theologian Augustine may have been, he was just one among many others.

An important aspect of Orthodox theology is the patristic consensus. Doing theology based upon the consensus of the Church Fathers and the seven Ecumenical Councils reflects the understanding among the early Christians that they shared a common corporate faith. This approach is best summed up by Vincent of Lerins: “Moreover, in the Catholic Church itself, all possible care must be taken, that we hold that faith which has been believed everywhere, always, by all.” (A Commonitory 2.6; NPNF Second Series, Volume XI, p. 132). See also, Irenaeus of Lyons’ boast to the Gnostics: “…the Church, having received this preaching and this faith, although scattered through the whole world, yet, as if occupying but one house, carefully preserves it (Against the Heretics 1.10.2, ANF Volume I, p. 331).

Thus, when the Orthodox Church confronted Calvinism in the 1600s, it already had a rich theological legacy to draw upon. Decree XIV of Dositheus’ Confession rejects the Calvinist belief in total depravity, affirming the Fall and humanity’s sinful nature, but stops short of total depravity.

We believe man in falling by the [original] transgression to have become comparable and like unto the beasts, that is, to have been utterly undone, and to have fallen from his perfection and impassibility, yet not to have lost the nature and power which he had received from the supremely good God. For otherwise he would not be rational, and consequently not man; but to have the same nature, in which he was created and the same power of his nature, that is free-will, living and operating (Leith 1963:496; emphasis added).

The Orthodox Memorial Service has a line that sums up the Orthodox Church’s understanding of the Fall: “I am an image of Your indescribable glory, though I bear the scars of my sins” (Kezios 1993:46). In summary, the Orthodox Church’s position is that human nature still retains some degree of free will even though subject to corruption by sin.

Biblical support for the Orthodox understanding of fallen human nature can be found in Paul’s speech to the Athenians. He commends the Athenians for their piety, noting they even had an altar dedicated to an unknown deity. Although their fallen nature prevented them from making full contact with the one true God, they nonetheless retained a longing for communion with God. Paul takes note of the spiritual longing that underlay the Athenians’ religiosity using it as a launching point for the proclamation of the Gospel:

From one man he made every nation of men, that they should inhabit the whole earth; and he determined the times set for them and the exact places where they should live. God did this so that men would seek him and perhaps reach out for him and find him, though he is not far from each one of us (Acts 17:26-27; emphasis added).

What Paul says here flies in the face of the Canons of Dort’s assertion that the unregenerate were incapable of spiritual hunger. Peter took a similar approach in his speech to Cornelius the Gentile centurion notes:

I now realize how true it is that God does not show favoritism but accepts men from every nation who fear him and do what is right (Acts 10:34-5).

Peter and Paul’s belief in God’s love for the nations is not a new idea. The Gentiles’ capacity to respond to God’s grace is a recurring motif in the Old Testament. Alongside Israel’s divine election was the theme of Yahweh as Lord of the nations in the Old Testament (see Verkuyl 1981:37 ff.)

It is important to keep in mind that the doctrine of election — the elect status of the Jewish people — is key to understanding Jesus’ messianic mission and much of Paul’s letters. Contrary to the expectations of many of the Jews of the time, Jesus’ messianic calling involved his bringing the Gentiles into the kingdom of God. This was a revolutionary doctrine — that the Gentiles could become saved through faith in the Messiah apart from becoming Jewish. This precipitated a theological crisis over the doctrine of election that underlie Paul’s reasoning in Romans and Galatians. In Romans 9-11, Paul had to explain and uphold God’s calling of Israel in the face of the fact that Israel had rejected the promised Messiah. To read the Calvinist understanding of double predestination into Romans 9 constitutes a colossal misreading of what Paul was attempting to do. Furthermore, it overlooks the great reversal of election that took place in the former Pharisee Paul’s thinking: the non-elect — the Gentiles — receive the grace of God and the elect — the nation of Israel — are rejected (Romans 10:19-21).

U – Unconditional Election

Whereas the first article of TULIP describes our fallen state, the second article describes God, the author of our salvation. The emphasis here is on the transcendent sovereignty of God whose work of redemption is totally independent of human will.

That some receive the gift of faith from God, and other do not receive it, proceeds from God’s eternal decree (Canons of Dort First Head: Article 6)

Calvin likewise affirms unconditional election through his rejection of the idea that our election is based on God’s foreknowing our response. He writes:

We assert that, with respect to the elect, this plan was founded upon his freely given mercy, without regard to human worth; but by his just and irreprehensible but incomprehensible judgment he has barred to door of life to those whom he has given over to damnation (Institutes 3.21.7, Calvin 1960:931; see also Institutes 3.22.1, Calvin 1960:932).

In another place, Calvin uses a medical analogy to describe double predestination:

Therefore, though all of us are by nature suffering from the same disease, only those whom it pleases the Lord to touch with his healing hand will get well. The others, whom he, in his righteous judgment, passes over, waste away in their own rottenness until they are consumed. There is no other reason why some persevere to the end, while others fall at the beginning of the course (Institutes 2.5.3; Calvin 1960:320).

Although the doctrine of total depravity is listed first, it is not the logical starting point of TULIP. The real starting point is in the second article, unconditional election. God’s transcendent sovereignty is the true starting point of Calvin’s soteriology. Karl Barth argued that it is Calvin’s insistence on God’s absolute sovereignty which characterizes Calvin’s theology; double predestination is but a logical outworking of this fundamental premise (Barth 1922:117-118).

The Calvinist doctrine of unconditional election is at odds with the Church Fathers who taught that predestination is based upon God’s foreknowledge. John of Damascus wrote:

We ought to understand that while God knows all things beforehand, yet He does not predetermine all things. For He knows beforehand those things that are in our power, but He does not predetermine them. For it is not His will that there should be wickedness nor does He choose to compel virtue. So that predetermination is the work of the divine command based on fore-knowledge. But on the other hand God predetermines those things which are not within our power in accordance with His prescience (NPNF Series 2 Vol. IX p. 42).

Another Church Father, Gregory of Palamas, asserted the same principle:

Therefore, God does not decide what men’s will shall be. It is not that He foreordains and thus foreknows, but that He foreknows and thus foreordains, and not by His will but by His knowledge of what we shall freely will or choose. Regarding the free choices of men, when we say God foreordains, it is only to signify that His foreknowledge is infallible. To our finite minds it is incomprehensible how God has foreknowledge of our choices and actions without willing or causing them. We make our choices in freedom which God does not violate. They are in His foreknowledge, but ‘His foreknowledge differs from the divine will and indeed from the divine essence.’ (Gregory of Palamas’ Natural, Theological, Moral and Practical Chapters, MPG 150, 1192A; Gabriel 2000:27).

Supported by the patristic consensus, the Orthodox Church in the Confession of Dositheus in no uncertain terms condemns the Calvinist doctrine of unconditional election.

But to say, as the most wicked heretics–and as is contained in the Chapter answering hereto-that God, in predestinating, or condemning, had in no wise regard to the works of those predestinated, or condemned, we know to be profane and impious (Decree III; Leith 1963:488).

L – Limited Atonement

One of the more controversial assertions in the Canons of Dort is the doctrine of limited atonement — that Christ died only for the elect, not for the whole world.

…it was the will of God that Christ by the blood of the cross, whereby He confirmed the new covenant, should effectually redeem out of every people, tribe, nation, and language, all those, and those only, who were from eternity chosen to salvation and given to Him by the Father (Second Head: Article 8; emphasis added).

Whereas the Canons of Dort is explicit in its affirmation of limited atonement, surprisingly a careful reading of Calvin’s Institutes does not yield any explicit mention of limited atonement (see Roger Nicole’s article).

There are a number of biblical passages that can be used to refute the doctrine of limited atonement. Biblical references commonly used to challenge the Calvinist position tend to be those that teach God’s desire for all to be saved, e.g., John 3:16:

For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life (emphasis added).

Another important passage is I Timothy 2:3-6:

This is good, and pleases God our Savior, who wants all men to be saved and come to a knowledge of the truth. For there is one God and one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus, who gave himself as a ransom for all men…. (emphasis added)

Another significant passage that specifically challenges the notion of limited atonement is I John 2:2:

He is the atoning sacrifice for our sins, and not only for ours but also for the sins of the whole world (emphasis added).

This passage is especially relevant for two reasons: (1) it specifically refers to Christ’s atoning death on the Cross, and (2) it teaches that Christ died not just for the elect (us) but also for the non-elect (the whole world). Calvin cited I John 2:2 three times, but what is surprising is that nowhere in his Institutesdid Calvin deal with the latter part of the verse. (The Biblical Reference index in the back of the Institutes (McNeill, ed.) shows that I John 2:2 is cited three times: 2.17.2, 3.4.26, and 3.20.20.)

The real challenge for those who appeal to the above passages lies in the semantic tactics used by Calvinists in which they argue that “all” and “the world” are not to be taken literally but as referring to only those predestined for salvation. (#7) Zacharias Ursinus, the German Reformer, understood “all” to refer to “all classes” rather than to individuals (Pelikan 1984:237). Similarly, Theodore Beza, Calvin’s colleague and successor, insisted that John 3:16 applied only to the elect. Roger Nicole’s explanation describes well the Calvinist strategy for reading biblical texts:

For instance, “all” may vary considerably in extension: notably “all” may mean, all men, universally, perpetually and singly, as when we say “all are partakers of human nature”; or again it may have a broader or narrower reference depending upon the context in which it is used, as when we say “all reached the top of Everest,” where the scope of the discourse makes it plain that we are talking about a group of people on which set out to ascend the mountain. It is not always easy to determine with assurance what is the frame of reference in view: hence controverted interpretations both of Scripture and of individual theologians. (emphasis added)

This hermeneutical approach imparts a certain imperviousness to Reformed theology; one either accepts their semantic perspective or one does not. The inductive method will not work here. This means that effective refutation of Calvinism cannot be carried out solely on the grounds of biblical exegesis. This longstanding impasse in Protestantism is an example of sola scriptura’s inability to create doctrinal unity on fundamental issues.

This is where historical theology can help us assess the competing truth claims. The advantage of historical theology is two-fold: (1) it enables us to understand the historical and social forces that shaped Calvinists’ exegesis and (2) it enables us to determine the extent to which Calvin’s theology reflected the mainstream of historic Christianity or to what extent Calvin’s theology became deviant and heretical.

Historical theology shows there existed a widespread belief among the Church Fathers in God’s universal love for humanity. Irenaeus of Lyons wrote.

For it was not merely for those who believed on Him in the time of Tiberius Caesar that Christ came, nor did the Father exercise His providence for the men only who are now alive, but for all men altogether, who from the beginning, according to their capacity, in their generation have both feared and loved God, and practised justice and piety towards their neighbours, and have earnestly desired to see Christ and to hear his voice (Against the Heretics 4.22.2).

St. John of the Ladder wrote:

God belongs to all free beings. He is the life of all, the salvation of all–faithful and unfaithful, just and unjust, pious and impious, passionate and dispassionate, monks and laymen, wise and simple, healthy and sick, young and old–just as the effusion of light, the sight of the sun, and the changes of the seasons are for all alike; ‘for there is no respect of persons with God.’ (1991:4)

The universality of Christ’s redeeming death can be found in the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, used on most Sundays in the Orthodox Church. During the words of institution over the bread and the wine, in one of the inaudible prayers, the Orthodox priest will pray a paraphrase of John 3:16:

You so loved Your world as to give Your only-begotten Son, that whoever believes in Him should not perish but have eternal life. …. Having come and having fulfilled the divine plan for us, on the night when He was delivered up, or rather gave Himself for the life of the world…. (Kezios 1996:24; emphasis added).

Probably the most resounding affirmation of this can be found at the end of each Sunday Liturgy when the priest concludes: “…for He alone is good and He loveth mankind.” (Kezios 1993:41)

I – Irresistable Grace

The fourth article attributes our faith in Christ to God’s effectual calling. The Canons of Dort stresses that God “produces both the will to believe and the act of believing also” (Third and Fourth Head: Article 14; see also Article 10). Faith in Christ is not the result of our choosing or our initiative, but is solely from God.

And as God Himself is most wise, unchangeable, omniscient, and omnipotent, so the election made by Him can neither be interrupted nor changed, recalled, or annulled; neither can the elect be cast away, nor their number diminished (Canon of Dort First Head: Article 11).

Furthermore, the Canons of Dort rejects the teaching that God’s converting grace can be resisted. The Third and Fourth Head: Paragraph 8 condemns the following statement: “That God in the regeneration of man does not use such powers of His omnipotence as potently and infallibly bend man’s will to faith and conversion….” Our free will has no bearing on our having faith in Christ. Faith in Christ is purely by the grace of God.

Although Calvin did not teach with the same starkness as the Canons of Dort the doctrine of irresistible grace, we find indications in his Institutes that he believed in the underlying idea. He wrote of God’s election being “inviolable” (Institutes 3.21.6, Calvin 1960:929), God’s unchangeable plan being “intrinsically effectual” for the salvation of the elect (Institutes 3.21.7; Calvin 1960:931); and God as the “intrinsic cause” of spiritual adoption (Institutes 3.21.7; Calvin 1960:941). Probably the closest we can find to an explicit endorsement of irresistible grace is Calvin’s paraphrase of Augustine.

There Augustine first teaches: the human will does not obtain grace by freedom, but obtains freedom by grace; when the feeling of delight has been imparted through the same grace, the human will is formed to endure; it is strengthened with unconquerable fortitude; controlled by grace, it never will perish, but, if grace forsake it, it will straightway fall…. (Institutes 2.4.14; Calvin 1960:308).

These passages lead to the conclusion that Calvin and the Synod of Dort shared the same belief in irresistible grace.

Orthodoxy rejects the doctrine of irresistible grace because this doctrine assumes the absence of human free will. The early Church Fathers — as noted in the section on total depravity — affirmed the role of free will in our salvation. One of the earliest pieces of Christian literature, the second century Letter to Diognetus, contains a clear affirmation of human free will and a rejection of salvation by compulsion. The author writes concerning the Incarnation:

He sent him as God; he sent him as man to men. He willed to save man by persuasion, not by compulsion, for compulsion is not God’s way of working (Letter to Diognetus 7.4; Richardson 1970:219).

Ultimately, the underlying flaw of Reformed soteriology is the emphasis on God’s sovereignty to the denial of love. The Calvinist insistence on God’s sovereignty undercuts the ontological basis for the human person. Closer inspection of the doctrine of irresistible grace brings to light a certain internal contradiction in Reformed theology: God’s free gift of grace is based on compulsion. Or to put it another way: How can a gift be free if there’s no freedom of choice? Love that is not free cannot be love. Love must arise from free choice. Bishop Kallistos Ware writes:

Where there is no freedom, there can be no love. Compulsion excludes love; as Paul Evdokimov used to say, God can do everything except compel us to love him (Ware 1986:76; emphasis in original).

Where there is no free will, there is no genuine love, nor can there be genuine faith. This in turn subverts and overthrows the fundamental Protestant dogma of sola fide. Ironically, Calvinism’s crowning glory also happens to be its fatal flaw.

Another reason why Calvinism is incompatible with Orthodoxy is its implicit monotheletism.In the seventh century, there arose a controversy as to whether Christ had one will or two. Monotheletism asserted that Christ had only one will (the divine) and bitheletism affirmed that Christ had two wills (human and divine working in harmony). The Sixth Ecumenical Council (Constantinople III) rejected monotheletism in favor of bitheletism. For an informed discussion of the theological debates surrounding the monotheletism heresy see Jaroslav Pelikan’s The Spirit of Eastern Christendom Vol. 2 (1973).

The Calvinists’ denial of human free will and their insistence on the dominance of the divine will over human will parallels the heresy of monothelitism, which insisted that Christ did not have two wills: a human will and a divine will. This assertion is made on the basis that the doctrine of the Incarnation rests on what constitutes the divine nature and what constitutes human nature. A defective anthropology (e.g., the denial of free will or the importance of physical flesh) leads to a defective Christology. Thus, the Reformed tradition’s implicit monotheletism points to a defective Christology and a significant departure from the historic Faith as defined by one of the Seven Ecumenical Councils.

P – Preservation of the Elect

Also known as the Perseverance of the Saints, the fifth article in TULIP addresses the troubling issue of Christians backsliding or falling into sin. Their failure to display the marks of election would seem to call into question the effectiveness of divine election. Again, we find the emphasis on God’s sovereignty:

Thus it is not in consequence of their own merits or strength, but of God’s free mercy, that they neither totally fall from faith and grace nor continue and perish finally in their backsliding; which, with respect to themselves is not only possible, but would undoubtedly happen; but with respect to God, it is utterly impossible, since His counsel cannot be changed nor His promise fail; neither can the call according to His purpose be revoked, nor the merit, intercession, and preservation of Christ be rendered ineffectual, nor the sealing of the Holy Spirit be frustrated or obliterated (Canons of Dort Fifth Head: Article 14).

Similarly, in response to questions about the status of the lapsed, Calvin’s position was: the elect cannot fall from salvation, even after their conversion, they will inevitably be saved (Institutes 3.24.6-7, Calvin 1960:971-3). Calvin writes:

For perseverance itself is indeed also a gift of God, which he does not bestow on all indiscriminately, but imparts to whom he pleases. If one seeks the reason for the difference–why some steadfastly persevered, and others fail out of instability–none occurs to us other than that the Lord upholds the former, strengthening them by his own power, that they may not perish; while to the latter, that they may be examples of inconstancy, he does not impart the same power (Institutes 2.5.3; Calvin 1960:320).

One could say crudely that the elect will be saved against their will, but the more nuanced approach is to say that the elect will inevitably choose to be saved because that desire has been implanted in them by God.

In contrast to Calvinism, the Orthodox understanding of the perseverance of the saints is based upon synergy — our cooperation with God’s grace, and deification — our becoming partakers in the divine nature. The Confession of Dositheus affirms the synergistic approach to salvation in contrast to the monergistic approach found in the Reformed confessions.

And we understand the use of free-will thus, that the Divine and illuminating grace, and which we call preventing grace, being, as a light to those in darkness, by the Divine goodness imparted to all, to those that are willing to obey this-for it is of use only to the willing, not to the unwilling-and co-operate with it, in what it requireth as necessary to salvation, there is consequently granted particular grace; which, co-operating with us, and enabling us, and making us perseverant in the love of God, that is to say, in performing those good things that God would have us to do, and which His preventing grace admonisheth us that we should do, justifieth us, and makes us predestinated (Leith 1963:487-8; emphasis added).

Irenaeus likewise teaches the perseverance of the saints, but from the perspective of theosis.

…but man making progress day by day, and ascending towards the perfect, that is, approximating to the uncreated One. …. Now it was necessary that man should in the first instance be created; and having been created, should receive growth; and having received growth, should be strengthened; and having been strengthened, should abound; and having abounded, should recover [from the disease of sin]; and having recovered, should be glorified; and being glorified, should see His Lord (Against the Heretics 4.38.3; ANF Vol. I p. 522).

The Orthodox approach to salvation provides the basis for a relational approach to salvation as opposed to the more forensic and mechanistic approach found in Western theology. This provides the basis for salvation as union with Christ and salvation as life in the Trinity.

Robert Arakaki

#1 Although closely related, Calvin and Calvinism are not synonymous. The relationship between Calvin and Reformed theology is more complex than most people realize. As a matter of fact, Alister McGrath warns against equating the two (1987:7). Also, it should be noted that some would dispute the centrality of predestination for Calvin’s theology. McGrath describes it as being an “ancillary doctrine, concerned with explaining a puzzling aspect of the consequence of the proclamation of the gospel of grace” (1990:169).

#2 See the edition by John T. McNeill (ed.) 3.21-25. For a discussion of the growing prominence of the doctrine in the successive editions of Calvin’s Institutes see Pelikan 1984:217-220.

#3 For a discussion of the theological issues at stake in the Remonstrant/Reformed controversy see Pelikan 1984:232-244.

#4 Unlike Lutheranism with its Formula of Concord, the Reformed tradition has no confessional statement with a similar normative stature (Pelikan 1984:236).

#5 In the early seventeenth century, the Patriarch of Constantinople, Cyril Lucaris, came under the influence of Reformed theology. In response to the challenge of Calvinism, the Orthodox Church responded by swiftly deposing Cyril, followed by convening a synodal gathering in Jerusalem. At that council, Calvinism was formally repudiated through The Confession of Dositheus, composed by the Patriarch of Jerusalem by that name (in Leith 1963:486-517. Thus, for Orthodoxy Calvinism is not a theological option.

#7 Medieval Catholic theologians who sought to defend double predestination in the face of I Timothy 2:4 would employ a more philosophical line of defense. They drew upon the distinction between God’s “antecedent will” and his “ordinate will” (Pelikan 1984:34).

References

ANF = Ante-Nicene Fathers.

MPG = Migne’s Patrologia Graecae

NPNF = Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers.

Barth, Karl. 1922. The Theology of John Calvin. Geoffrey W. Bromiley, translator. English translation, 1995. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Calvin, John. 1960. Institutes of the Christian Religion. The Library of Christian Classics Vol. XX. John T. McNeill, ed. Translated by Ford Lewis Battle. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press.

Dort, Synod of. 1619. Canons of Dort. <http:www.ccel.org/creeds/canons-of-dort.html> Site visited August 11, 2012.

Gabriel, George S. 2000. Mary: The Untrodden Portal. Ridgewood, New Jersey: Zephyr Books.

Hick, John. 1968. Evil and the God of Love. Great Britain: Fontana Books.

Kelly, J.N.D. 1960. Early Christian Doctrines. Revised Edition. New York: Harper & Row Publishers.

Kezios, Spencer T., ed. 1993. The Divine Liturgy. Leonidas Contos, translator. Northridge, CA: Narthex Press.

Kittelson, James M. 1986. Luther the Reformer: The Story of the Man and His Career. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Augsburg Publishing House.

Leith, John H., ed. 1963. Creeds of the Churches. Atlanta: John Knox Press.

Pelikan, Jaroslav. 1984. Reformation of Church and Dogma (1300-1700). The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine. Volume 4. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Richardson, Cyril C., ed. 1970. Early Christian Fathers. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc.

United Presbyterian Church. 1970. The Book of Confessions. The Constitution of the United Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, Part I. Second Edition. New York, NY: The United Presbyterian Church in the United States of America.

Verkuyl, Johannes. 1981. “The Biblical Foundation for the Worldwide Mission Mandate.” In Perspectives on the World Christian Movement: A Reader, pp. 35-50. Ralph D. Winter and Steven C. Hawthorne, editors. Pasadena, California: William Carey Library.

Ware, Kallistos (Timothy). 1963. The Orthodox Church. New Edition, 1997. London: Penguin Books.

__________. 1986. The Orthodox Way. Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

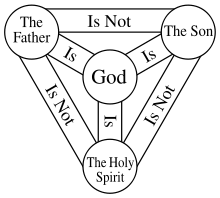

Western Christianity’s foregrounding of the ousia (being) of God has led to logical difficulties. It has resulted in theologians having to make statements that resemble Zen koans used by Buddhist monks. A common explanation often goes like this: the Father is God, the Son is God, the Holy Spirit is God; but the Son is not the Father, and the Son is not the Holy Spirit; but there is not three gods but only one God. Formulation like this often frustrate and bewilder many. It is radically different from the Eastern understanding of the Trinity as the communion of three Persons who share in the same Essence.

Western Christianity’s foregrounding of the ousia (being) of God has led to logical difficulties. It has resulted in theologians having to make statements that resemble Zen koans used by Buddhist monks. A common explanation often goes like this: the Father is God, the Son is God, the Holy Spirit is God; but the Son is not the Father, and the Son is not the Holy Spirit; but there is not three gods but only one God. Formulation like this often frustrate and bewilder many. It is radically different from the Eastern understanding of the Trinity as the communion of three Persons who share in the same Essence. A Theological Continental Divide

A Theological Continental Divide

Recent Comments