Revised 3 March 2014

Martin wrote:

I have a question. Baptists and Pentecostals say infant baptism is not biblical. Do we find infant baptisms in the Bible? I heard someone say that this practice started around year 200. Where can I find the earliest teachings about infant baptism? When is the first time the early Fathers mentioned it? What does the Orthodox Church teach about this? How can a baby be “born again” with no personal faith before he/she has heard the Gospel being preached? Or what is the point of infant baptism? What difference is there between Catholic, Lutheran and Orthodox infant baptism?

My Response

You asked some very good questions about the rationale for infant baptism. I will attempt to answer each of your questions below but before I do so I need to discuss the role of Scripture in the various Christian traditions. But feel free to jump to Question 1.

For Protestants the Bible is the preeminent source of theology. This arises from the doctrine of sola scriptura (Scripture alone). But what does one do when Scripture is silent or the biblical text is not clear? Protestants respond to this ambiguity in several ways: (1) some will argue that this makes the practice unbiblical and thus prohibited; (2) some will argue that this is a matter of liberty subject to personal opinion or conscience, and (3) some will attempt to rely on historical precedents to guide them. This accounts for the wide array, even contradictory, positions Protestants hold on baptism, including infant baptism.

Orthodoxy base its doctrines and practice on Tradition (with a capital ‘T’), a combination of oral tradition and written tradition (II Thessalonians 2:15). Orthodoxy also relies on Christ’s promise that the Holy Spirit would guide the Church into all truth (John 16:13). Thus, with respect to the Orthodox approach to infant baptism we find an ancient practice widely accepted that in time was formally acknowledged by the Ecumenical Councils.

In contrast to Orthodoxy’s conciliar approach to church authority, Roman Catholicism holds to a monarchical understanding of church authority. It views the Pope as having ultimate authority in matters of faith and practice. Thus, on matters where Scripture is silent the Pope speaks. This view stems from the understanding that the Pope is the successor to the Apostle Peter and thus has the ultimate authority to interpret Scripture and define Tradition. This monarchical understanding of the Bishop of Rome arose in the Middle Ages. Orthodoxy rejects this as a departure from the conciliar approach of the early Church. While it has roots in the early Church, the Great Schism of 1054 resulted in the Church of Rome going its own way. It began to adopt innovative teachings and practices that many found objectionable. This resulted in the Protestant Reformation. In order to counter the authority of the Pope, Luther and the other Reformers invoked the authority of Scripture. This led to sola scriptura as a foundational principle for Protestantism.

With this new theological method of sola scriptura, Tradition — oral tradition, the church fathers, and Ecumenical Councils — took on a subordinate position to Scripture. Orthodoxy rejects the Protestant subordination of Tradition to Scripture because it views written and oral tradition as two sides of the same coin, integral and inseparable to the other (II Thessalonians 2:15). Understanding these differences will help you understand how I put together my answer to your questions. In answering your questions I seek to show how Orthodoxy is at its core biblical in its doctrine and practice while also consistent with the early Church founded by the Apostles.

1. Do we find infant baptisms in the Bible?

A lot depends on the question we ask. If you ask a question the wrong way, you are quite likely to get an incorrect answer. If we take your question about infants as a starting point, we can extend it to adults, teenagers and elderly as well. Just as there is no teaching in the Bible in support of infant baptism so likewise there is no teaching in the Bible in support of teenagers or of senior citizens being baptized.

A better way to frame the question is to ask: What does the Bible teach about covenant initiation? We find throughout the Bible God establishing covenants (contracts) and people entering into a covenant relationship by means of a certain ritual act. In Genesis 17 God invites Abram to enter into a covenant via circumcision. What is the age span of those circumcised in Genesis 17? Anywhere from a new born male child eight days old (Genesis 17:12), a teenage boy (Ishmael was 13 years old at the time; see Genesis 16:16), to a male senior citizen (Abraham was 99 years old at the time; see Genesis 17:1).

When we look at Peter’s Pentecost Sermon we find some interesting teaching about covenant initiation. At the climax of the sermon Peter exhorts:

Repent and be baptized, every one of you, in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins. And you will receive the gift of the Holy Spirit. The promise is for you and your children and for all who are far off—for all whom the Lord our God will call. (Acts 2:38-39: NIV, emphasis added)

The phrase “you and your children” implies both the adult listeners and their offspring. The Greek word for “offspring” (τεκνος, teknos) can include young children as well as those grownup. If we look at the opening quotation from Joel in Acts 2:17 Peter is describing those receiving the Holy Spirit broadly, not restrictively. Notice the language used: sons versus daughters, young men versus old men. In Peter’s Pentecost sermon water baptism is closely linked to Spirit baptism. The Orthodox Church maintains this linkage by administering Chrismation immediately following baptism.

Another element we need to take into consideration is the fact that the Bible teaches the salvation of families. Luke in his account of the conversion of the Philippian jailer wrote:

At that hour of the night the jailer took them and washed their wounds; then immediately he and all his family were baptized. The jailer brought them into his house and set a meal before them; he was filled with joy because he had come to believe in God—he and his whole family. (Acts 16:33-34; NIV, emphasis added)

The phrase “his whole family” can be read to include little children and infants. This emphasis on the family unit parallels the first Passover when the Israelites gathered in a home to celebrate a Passover meal (Exodus 12). The blood of the sacrificed lamb was smeared over the door of the house, not on individuals. This contrasts with the modern mindset that elevates the individual over the family, and which emphasizes individualized faith over believing together with others.

Baptism is the new circumcision. Just as circumcision was the rite of initiation into the old covenant, so likewise baptism is the rite of initiation into the new covenant founded by Christ on the Cross.

In him you were also circumcised, in the putting off of the sinful nature, not with a circumcision done by the hands of men but with the circumcision done by Christ, having been buried with him in baptism and raised with him through your faith in the power of God, who raised him from the dead. (Colossians 2:11-12; NIV)

Orthodoxy does not view the sacrament of baptism as magic. Rather, it understands baptism as making one part of God’s family. It is the responsibility of the parents and godparents to make sure the baptized child learn about Christ and the Christian way of life. In II Timothy 3:15 we learn that Timothy was exposed to the Old Testament at a very early age, from infancy. As the child grows up he or she will begin to make their own decisions and develop a lively personal faith in Christ. If there is “magic,” it is the powerful influence a loving and faith-filled environment at home and church will have on a child. One of the biggest threats to this model of Orthodox discipleship is a mindless nominalism in which people do church things because it is part of their ethnic heritage and are not able to give a reasoned response to youths asking questions about the doctrines and practices of the Church.

2. Where can I find the earliest teachings about infant baptism?

The thing to keep in mind is that the early church allowed for infant baptism, it did not mandate the baptizing of infants. It was a common practice among Christians and there was very little protests against it. Infant baptism became the standard practice with the conversion of entire people groups. When a ruler converted, he would be followed by his supporters and their entire families. It is also important to keep in mind that given the high mortality rates at the time many parents would seek to baptize their child especially if death was imminent.

An overview of the early church’s attitude towards infant baptism can be found in Jaroslav Pelikan’s The Emergence of the Christian Tradition (100-600), (pp. 290-292). The earliest mention of infant baptism was by Tertullian (c. 160-220) who voiced skepticism about the practice of baptizing infants. The renowned Alexandrian theologian, Origen (185-254), admitted infant baptism to be part of the church tradition going back to the Apostles even as he struggled to articulate a clear rationale for the practice. With the church father Cyprian (c. 200-258) we find infant baptism defended on the basis of original sin. Of the three sources mentioned here only Cyprian is regarded as a church father. J.N.D. Kelly in Early Christian Doctrines noted while the sacraments of baptism, chrismation, and the Eucharist were universally practiced in the early Church there was very little evidence of a systematic sacramental theology at the time of the fourth and fifth centuries (p. 422 ff.). This points to the sacraments and Liturgy preceding theology in the early Church.

Dating infant baptism to AD 200 is based on a restrictive reading of the evidence. The evidence is clear that the first mention of infant baptism took place circa 200 which means that its origin can be placed earlier than 200. Given Origen’s testimony that infant baptism has apostolic roots and the absence of contrary evidence, we can assume that infant baptism dates back to the early days of the church, even the Apostles. Given Christianity’s Jewish roots and the established practice of infant circumcision among Jews, it should be no big leap to infant baptism among Christians.

3. What does the Orthodox Church teach about this?

Orthodoxy accepts infant baptism as an ancient practice. For Orthodoxy the Ecumenical Councils comprise an important authority for faith and practice. We find in Canon 84 of the Quinisext Council (692) instructions on how to handle those who claimed to have been baptized as infants but unable to provide witnesses to support that claim—baptize them provisionally. Van Espen in his commentary on Canon 13 of the Council of Nicea (325) noted “that after baptism and confirmation, the Eucharist was given even to infants.” The implicit acceptance of infant baptism by the major church councils points to infant baptism being a widely accepted practice among Christians.

From the standpoint of church history infant baptism was an ancient practice accepted by the Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Oriental Orthodox churches. It was even accepted by the mainstream Protestant churches: Lutheran, Reformed, and Anglican. But it was rejected by the radical Anabaptists then by the Baptists. In time it became popular among many Protestants, especially Evangelicals and Pentecostals. Thus, the strict credobaptist position which rejects paedobaptism is a doctrinal novelty that originated in the 1500s and marks a major departure from the historic Christian faith.

4. How can a baby be “born again” with no personal faith before he/she has heard the Gospel being preached? Or what is the point of infant baptism?

This question defines faith in Christ narrowly in terms of an intellectual acceptance of certain precepts on who God is (God is loving and just), what human nature is like (sinful and fallen), what Christ has done for us (died on the Cross for our sins), and the expected response (saying the “sinners prayer” to receive Christ into your heart). This intellectual understanding of faith has resulted in certain branches of Protestants debating among themselves about the “age of accountability.”

Evangelicals have projected their subjective emotionalism into the phrase “born again.” Being “born again” is not an emotional experience as it is a new life in Christ. Once we were living life apart from Christ, but now we put our faith in Christ and come under his authority through baptism. In Genesis 17 when Abram entered into a covenant with Yahweh via circumcision, he took on a new name “Abraham” signifying his new life as a follower of Yahweh. Genesis 17 is about a change in relationship with God, it was not about Abram having an emotional “born again” experience.

If we look at what the Bible has to say about the spiritual capacity of young children the answer might surprise us. Luke reports that when the Virgin Mary entered into Elizabeth’s home and greeted her that the baby inside Elizabeth’s womb “leaped for joy.” (Luke 1:41, 44) John the Baptist’s pre-natal response to the presence of the Incarnate Logos points to our desire for God in the primordial core of our being. An infant may not have a fully developed intellect, but it possesses the ability to respond to love. This is because the ability to love and respond in love is foundational to our humanity. Faith as the ability to trust someone is critical to our being able to love another person. That is why the betrayal of trust is so damaging to our being able to love another. This relational approach to faith can be seen in Orthodoxy’s Holy Week services which mourn Judas’ betrayal of Christ. This is something I did not learn as a Protestant.

But what is Jesus’ attitude about the spiritual capacity of children? The incident of Jesus blessing the little children appears in all three synoptic Gospels. Where Matthew and Mark used the general term for children παιδιον (paidion), Luke used the more precise term βρεφος (brephos) which can mean infant and new born, and even unborn children.

But Jesus called the children to him and said, “Let the little children come to me, and do not hinder them, for the kingdom of God belongs to such as these. I tell you the truth, anyone who will not receive the kingdom of God like a little child will never enter it.” (Luke 18:16; NIV)

This incident contains a powerful lesson about the accessibility of the kingdom of God. It is for those who have an open heart like little children. It does not teach that the children should wait until they are old enough to understand before they can enter the kingdom of God. The phrase “enter the kingdom of God” is a synonym for entering into a covenant relationship with Christ. This phrase crops up in Jesus’ night conversation with Nicodemus (see John 3:5). Read in the larger context of the entire chapter Nicodemus’ conversation with Jesus in the first half of John 3 dovetails with the second half which describes how Jesus’ baptism was superseding that of John the Baptist. The message behind the need to be “born again” was not about an emotional spiritual experience but about a new life in Christ through the sacrament of baptism.

Our understanding of the spiritual capacity of children will be consequential for our understanding of their place in church. Because the sermon is the focal point of many Protestant worship services, many infants are sent off to the child care ministry. They are not expected to be in main worship service. It is by and large assumed that the main worship service is for adult members.

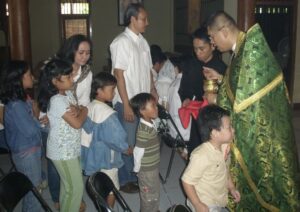

In Orthodoxy the general understanding is that children, even young infants, belong in the Liturgy. They may not fully comprehend what is going on but they are in the presence of God. Orthodoxy believes this exposure is important for their spiritual growth. Furthermore, as a sign of their inclusion in the kingdom of God, children are given Holy Communion. The practice in many Orthodox parishes is to let the children go up first to receive Communion followed by the grownups. For me this stands in stark contrast to my Protestant experience where I would see parents go up to receive Communion while their children remained behind because they have not yet made a profession of faith.

5. What difference is there between Catholic, Lutheran and Orthodox infant baptism?

All three traditions baptize infants but the Roman Catholic and Lutheran churches tend to defer Confirmation and Communion until the child reaches a certain age. The practice in Orthodoxy is to baptize infants about a month after they are born, and to give them the sacraments of Chrismation and Holy Communion in the same service as baptism. This makes them full members of the Church.

It is a touching sight to see parents carrying babies up for Communion, followed by a line of toddlers and teenagers, then adults and seniors. The demographics of a line for Orthodox Communion is something you won’t find in either Roman Catholic or Lutheran parishes Orthodoxy is for people of all ages!

Robert Arakaki

Recent Comments