Scottish Communion Service source

A Response to Rev. Peter Leithart’s “Puritan Sacramentalism”

The Rev. Peter Leithart wrote a provocative article “Puritan Sacramentalism” which appeared in First Things. Already his article has elicited at least two responses by Orthodox Christians on Orthodoxy and Heterodoxy: Gabe Martini’s “On Leithart’s Puritans and the Purity of Sacraments” and Father Andrew Stephen Damick’s “Is Liturgy Magic? A Response to Peter Leithart’s Puritan Sacramentalism.” Fr. Andrew and Gabe Martini in their response articles explained how Rev. Leithart misunderstood the nature and purpose of the preparatory rites in the Liturgy.

What I seek to do here is examine the issue of sacramentalism which is key to Leithart’s argument.

What Makes the Difference?

The issue here is: Do we truly partake of Christ’s body and blood in the Eucharist? This doctrine of the real presence has been held by Christians from the early days of the Church. Unlike low church Evangelicals who view the Lord’s Supper as just a symbol, Leithart’s understanding is much closer to the historic doctrine of the real presence. Like the Reformers and even the Puritans, Rev. Leithart affirms the real presence of Christ’s body and blood in the Eucharist.

But the question that Rev. Leithart must answer is: What makes the difference between a Holy Communion service where the bread and the grape juice are just symbols and a Holy Communion service where one truly partakes of the body and blood of Christ? Is it whether one holds to the doctrine of the real presence or something more? Is saying the Words of Institution enough?

There was a time when I was a high church Calvinist attending a low church Evangelical congregation. My former home church believed that the bread and the grape juice distributed at the monthly Communion service were symbols to help us remember and appreciate what Jesus did for us on the Cross. However, as a result of reading Reformers like Luther and Calvin, and also the early Church Fathers, I had come to accept the doctrine of the real presence. So while my fellow church members sitting next to me saw the piece of bread and the grape juice as symbolic reminders, I saw myself as partaking of Christ’s body and blood. I held to this view until one day I was at a Graduate Christian Fellowship retreat. When I walked into the room where the Communion service was to be held I thought to myself: “They’re right! It is just a symbol because it’s not the real thing. It is just a symbol because they have no priestly authority to bless the bread and the wine.” Because there was no priestly authority the bread and the wine remained just bread and wine, and could only serve as symbolic reminders of Christ’s death on the Cross. This started me thinking about what goes on in the Liturgy and the Eucharist, and how Protestant worship differs from Orthodox worship.

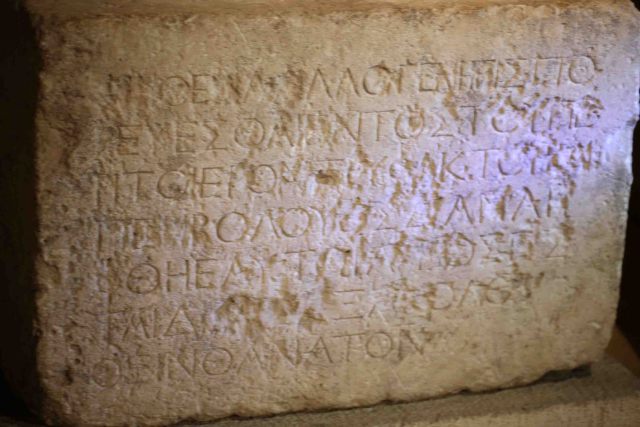

Ancient Near Eastern Covenant/Treaty source

I learned from the Reformed tradition that running through Scripture, both Old and New Testaments, is the theme of the covenant. So if Jesus Christ is the Suzerain who inaugurated the New Covenant then the implications are staggering. The Bible is more than just an instruction manual, it is a covenant document for the covenant community, the Church. This implies that just as the old Israel had a Temple and ordained priesthood, so likewise the new Israel would have a Temple and a priesthood. We find this in Hebrews 13:10 which refer to the Christians having an altar that the Jewish priests could not partake of and Isaiah 66:23 where God promised that in the Messianic Age he would take from the Gentiles certain men for the priesthood. This means that at every Sunday Eucharist we as vassals partake of the covenant meal with our Suzerain Lord – Jesus Christ. This means that the authority of an Orthodox priest is grounded in the authority structure of the New Covenant. Just as the Old Testament priesthood had an authority structure, so also does the New Covenant priesthood have a covenant authority structure.

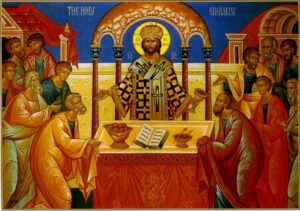

Eucharist in the Early Church

In the early Church the Eucharist was celebrated only by the bishops, the successor to the Apostles, or a priest who served under him. Ignatius of Antioch served as bishop of St. Paul’s home church in Acts 13. Remember, Ignatius is held by tradition to be the child in the Gospel Christ put on his lap as a lesson to the Apostles (Mark 9:56). Ignatius likely knew several of the Apostles for decades as a young man and served early in the second century just after the original Apostles died. He was the first generation of bishops charged to keep the Tradition – Paul’s exhortation in 2 Thessalonians 2:15. Ignatius wrote:

It is not lawful either to baptise or to hold an “agape” without the bishop; but whatever he approve, this is also pleasing to God, that everything which you do may be secure and valid. (To the Smyrnaeans 8.2)

Be careful therefore to use one Eucharist (for there is one flesh of our Lord Jesus Christ and one cup for union with his blood, one altar, as there is one bishop with the presbytery and the deacons my fellow servants), in order that whatever you do you may do it according unto God. (To the Philadelphians 4.1)

The bishop’s authority to preside over the Eucharist is rooted in the Church’s covenant structure. This was the answer to my predicament as a high church Calvinist. When the priest together with the congregation as a covenant community prays for the Holy Spirit to descend upon the bread and the wine then a real change takes place in the Eucharist. What makes the difference between any of the best even the fullest Protestant Lord’s Supper and a valid Orthodox Eucharist is the bishop’s covenant authority to pray for the Holy Spirit to descend upon the gift offered on the altar.

There is a covenant authority structure that undergirds Orthodoxy and it is a sad fact that as a schismatic breakaway movement Protestantism lies outside this covenant structure. Protestants can claim quoting from the Bible in the Holy Communion service is sufficient but for unauthorized person (not properly ordained by a bishop) to undertake a covenant act apart from proper covenant order is unauthorized and therefore invalid. Furthermore, no early Church Father taught that merely invoking the Words of Institution is sufficient for a valid Eucharist. This application of sola Scriptura to the Lord’s Supper is a doctrinal and liturgical innovation with no grounding in historic Christianity.

Does this mean that all Protestant celebrations of the Lord’s Supper in this manner are completely without grace and meaningless? The Orthodox are not prepared to say just where the Holy Spirit might indeed choose to bless . . . or in what way He might bless. We do not know the mysterious ways of the Holy Spirit. But we can say that we are assured that the fullness of blessing is assured at the Orthodox Eucharist, premised upon the historical continuity of the Orthodox Church, the Scriptures they received from the Apostles, and the declarations of the Ecumenical Counsels.

What makes the bread and the wine the body and blood of Christ is the Holy Spirit who comes down on the gifts offered up by the people of God. The descent of the Holy Spirit on the gifts at a “typical” Sunday Liturgy are a miracle much like the descent of fire from heaven on the prophet Elijah’s sacrifice on Mount Carmel in 1 Kings 18. Cyril of Jerusalem in his Catechetical Lectures stated:

Then having sanctified ourselves by these spiritual Hymns, we beseech the merciful God to send forth His Holy Spirit upon the gifts lying before Him; that He may make the Bread the Body of Christ, and the Wine the Blood of Christ; for whosoever the Holy Ghost has touched, is surely sanctified and changed (Lecture XXIII.7; NPNF vol. 7 p. 154; emphasis added.)

For Orthodox Christians today this is all very familiar because we follow the same Liturgy as that used by Cyril in the fourth century. The Liturgy we use has its source in Apostolic Tradition. Paul in 1 Corinthians 11:23:

For I received from the Lord what I also passed on to you: The Lord Jesus, on the night he was betrayed, took bread . . . . (Emphasis added.)

The phrases “received from” and “passed on” point to a traditioning process. The early Christians did not say: “Let’s see what the Bible has to say about how to conduct a Holy Communion service”; instead they would look to their bishop who had been discipled and ordained by the Apostles. In the early days the New Testament as we know it did not exist; what the early Christians had were the Old Testament writings, copies of the Gospels and some of Paul’s writings, and what the bishop had heard from the Apostles. The Liturgy we use today has been guarded by the Church throughout history. It was passed on from generation to generation beginning with the Apostles who passed it on to their disciples, the bishops (cf. 2 Timothy 2:2).

This in turn leads to some hard questions for Rev. Leithart. Does he have the covenantal authority to celebrate the Eucharist? I would say that as a Presbyterian, Rev. Leithart cannot claim apostolic succession. This link was severed at the Protestant Reformation. So a Protestant minister can dress himself up with vestments and recite ancient liturgical formulas but without valid covenant authority which comes through apostolic succession it is all going through the motions. It is valid covenantal authority, not “high church” ceremonialism, that makes the difference in a valid Eucharist. It is valid covenantal authority via apostolic succession that is key to what Leithart calls “high sacramentality.”

Rev. Peter Leithart either misunderstands or misrepresents Orthodoxy if he thinks that the elaborate ceremonials are just that – preparatory rites. The elaborate ritual actions and prayers are intended to prepare us to receive Christ in the Eucharist. If Orthodox worship is elaborate, it is so because it came out of the Jewish liturgical tradition described in the book of Exodus and reflects the rich liturgical worship up in heaven as found in the book of Revelation.

Catholic and Protestant?

The root cause of Peter Leithart’s predicament lies in his attempting to be (1) both an ancient Orthodox/Catholic and Protestant at the same time, and (2) both historically sacramental and Puritan at the same time. It doesn’t work. It can’t work because it flies in the face of church history and the witness of the early Church Fathers. Where low church Evangelicalism holds to sola Scriptura (Bible alone) and the memorialist understanding of the Lord’s Supper, Orthodoxy holds to the Holy Tradition – the teachings and practices of the Apostles – which the Apostles entrusted to the Church Fathers who in turn handed it down to their successors (2 Timothy 1:13-14). Holy Tradition consists of Scripture and how the Apostles understood the Scriptures. Holy Tradition also consists of how the Lord’s Supper was to be celebrated and the understanding of the real presence in the Eucharist. While the low church Evangelicals and liturgical Orthodox Christians may be radically at odds with each other’s positions, there is a certain logical consistency to their respective theology and worship. It is people like Rev. Leithart who seek to be both sacramental and Protestant at the same time who end up in such convoluted theological straits. It’s one thing to go a contemporary worship service, but it’s another thing to attempt to emulate historic Christian worship while at the same time disdaining the ancient historic Church founded on the Apostles and refusing to submit to her leaders who share a common ordination from the Apostles.

Peter Leithart tells how on Christmas Eve he first attended a low church service that included a Neil Young song and a jazzy rendition of a “Charlie Brown Christmas” song, then afterwards attended a high church midnight Mass at an Episcopal cathedral. All this left me puzzled. Why would Rev. Leithart, a PCA minister, attend these two wildly divergent services? What about his Reformed church tradition? It appears he is currently in limbo between low church Evangelicalism and high church Episcopalianism, and is straining hard to devise a new alternative between the two.

That Rev. Peter Leithart is without question well read and well educated is obvious. So it is distressing to us – Fr. Andrew Stephen Damick, Gabe Martini, and this writer — when he misrepresents the Orthodox tradition. It seems that he is earnestly seeking to reconnect with the early Church but hasn’t quite figured out how to let go of his Reformation convictions. This is a hard step that one must make if one wishes to be in communion with the early Church. I would encourage Rev. Leithart to continue reading the early Church Fathers in context and discuss his concerns with a knowledgeable Orthodox Priest – perhaps one who knows well his Reformed background and concerns. One thinks of Father Josiah Trenham, who studied at Westmont College then Reformed Theological Seminary. Rev. Leithart should also seek to imbibe the spirit of Orthodox worship by visiting a local Orthodox church as often as possible, and again, discuss his concerns and the Why questions with a knowledgeable priest. All too often Protestants are like tourists who think they understand the foreign culture they are visiting, but there are significant cultural differences between Protestantism and Orthodoxy. Protestants should beware of thinking they already understand what is going on in an Orthodox Liturgy. I would also encourage Rev. Leithart to put aside his Puritan glasses when he reads the early Church Fathers, and remember the wisdom of “Praxis leads to understanding” and we “Obey in order to understand.”

Advice for Curious Protestants

In light of the fact that Great Lent has just begun I suggest that curious Protestants use this as a time to read through Cyril of Jerusalem’s Catechetical Lectures and compare this ancient lecture series with the way today’s Orthodox churches celebrate Lent, Holy Week, and Easter (Pascha). Many will be surprised to see how similar Orthodox worship today is to the worship of the early Church. They can also reflect on what makes the difference between Puritan sacramentalism and the real presence of Christ’s body and blood in the Orthodox Eucharist.

Robert Arakaki

Recent Comments