A Response to Pastor Toby Sumpter

On 3 March 2016, Pastor Toby Sumpter posted on Reformation21 “An Apostolic Case for Sola Scriptura.” In this article he argues that canon formation of the New Testament proves the Protestant doctrine of sola scriptura. He writes:

In fact, there is a strong case to be made that the apostles and first Christians knew what books would form the New Testament canon very early on. The reason they knew was because the task of writing the New Testament Scriptures was one of the central purposes of the office of apostles. (Emphases added)

And,

The center of the evidence for a largely completed canon by the death of the apostles is grounded in understanding the office of apostle itself. (Emphasis added)

Toby Sumpter’s attempt to prove a very early New Testament canon (before AD 100 or even during the lifetime of the Apostles) makes sense in light of recent Reformed and Orthodox apologetics debate over sola scriptura. One major criticism of sola scriptura is the argument that if it took several centuries for the New Testament canon to emerge then that means the early Church functioned quite well without sola scriptura. This in turn raises the question whether sola scriptura is necessary.

All too often Protestant attempts to defend sola scriptura confuse the writing of the New Testament texts (corpus formation) with that writing being recognized as uniquely inspired (canon formation). While closely related, the two are not the same. Among conservative Christians there is little debate about the New Testament texts having been written in the latter half of the first century. The difference lies more with the Church’s recognizing the texts as divinely inspired, that is, as Scripture.

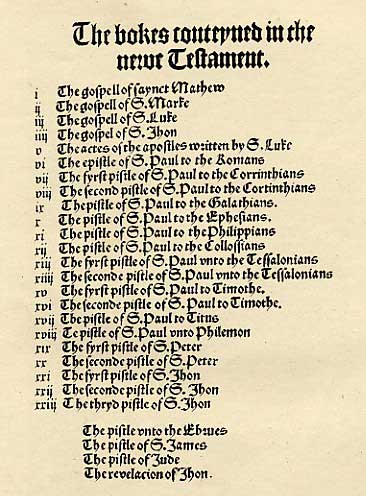

Where did this list come from? Who made it? Source

There are two competing theories of how canon formation took place. A prolonged canonization process would suggest the Church functioned under oral Apostolic tradition for the first few centuries and without sola scriptura. (Remember, John Mark did not write his synoptic gospel first for at least twenty years.) A compressed canonization process would leave little room for oral Apostolic Tradition. A very early completion to the canonization process would give rise to a listing of authoritative New Testament (canon) to guide the early Church in matters of faith and practice. If one takes the extreme position – as does Toby Sumpter – that the New Testament canon was completed while the Apostles were still living then there was zero room for oral Apostolic tradition to guide the early Church. This is because the early Church had a complete list of Scripture from the get go (as argued by Toby Sumpter).

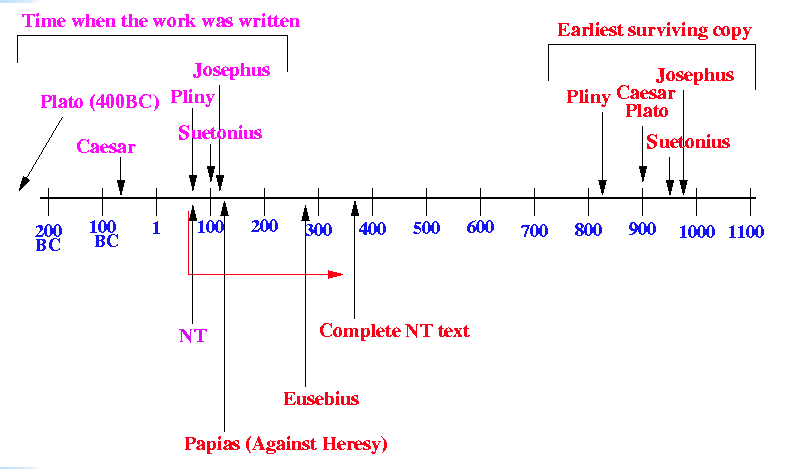

Chart showing the mainstream understanding of canon formation – Source

The New Testament Project?

Pastor Sumpter puts forward the interesting theory that in light of the Great Commission the Apostles devoted themselves to the production of canonical Scriptures for the Church.

Here, I argue that the apostles were quite conscious of this goal. Jesus had entrusted to them the “testimony” not merely for a small band of Jews in Jerusalem, but they were to be witnesses throughout Judea and Samaria and to the ends of the earth. How would that testimony reach the ends of the earth intact without devolving into an elaborate telephone game? The apostles and their assistants almost immediately began writing. This is because the apostles knew that their office was responsible for preserving and passing down the authoritative testimony of the gospel of Jesus. This is why every New Testament book was written or sponsored by an apostle. (Emphases added)

From the above excerpt we find Pastor Sumpter making at least three claims: (1) that the Apostles were conscious of their responsibility to write canonical Scripture, (2) that Jesus made writing part of the Great Commission, and (3) that the Apostles in obedience to this mandate began writing canonical Scripture right away. But does Scripture support any of these claims?

First, if the Apostles were “quite conscious of this goal,” then we would expect to find them discussing their responsibility to produce an authoritative collection of writings that testify to Jesus Christ. Where’s the evidence? A careful search of the Gospels, the book of Acts, and the letters by Paul and other Apostles leaves us empty handed. We find is that the Apostles did write but wrote when the occasion called for it (Romans 15:15; 1 Corinthians 4:14, 5:9-11; 2 Corinthians 2:3-4, 13:10; Galatians 1:20; Philippians 3:1; 2 Thessalonians 4:9, 5:1; 1 Timothy 3:14; Philemon 19-21; 1 Peter 5:12; 2 Peter 3:1; 1 John 1:4, 2:1; Jude 3).

Second, there is no evidence that Jesus made writing part of their apostolic calling. When we look at the Great Commission passage in Matthew 28, and other similar passages: Mark 16:15-20, Luke 24:45-49, John 20:21, and Acts 1:1-8, we find not a single shred of evidence indicating that Jesus ever did so. As a matter of fact, in the longer ending to Mark’s Gospel Jesus commands the Apostles: “Go into all the world and preach (κηρυξατε) the good news to all creation.” Likewise, in Luke 24:47 we read: “repentance and forgiveness of sins will be preached (κηρυχθηναι) in his name to all nations.” The Greek κηρυσσω has the sense of public proclamation by voice; it would be a stretch to say that it means writing. According to Kittel’s Theological Dictionary of the New Testament one of key qualifications of a herald (κηρυξ) was a good voice (vol. III p. 686). The sole exception is the book of Revelation where Christ tells John: “Write (γραψον), therefore, what you have seen, what is now, and what will take place later.” (Revelation 1:7, cf. 21:5) However, this command applies only to the book of Revelation. If Toby Sumpter’s argument did hold up, we would have seen other earlier commands for the other New Testament texts but no such evidence for this can be found.

Third, there is the fact that none of the New Testament texts have been dated back to the 30s or 40s. The earliest New Testament texts are either Paul’s letter to the Galatians or 1 Thessalonians. Scholars estimate that Galatians was likely written after AD 52 and that 1 Thessalonians has likewise been estimated to have been written in the early 50s. Mark’s Gospel is believed to have been written around the time of the fall of Jerusalem in AD 70. Matthew’s Gospel and Luke’s Gospel have been estimated to have been written circa AD 80. Furthermore, much of Paul’s letters were written in response to pastoral emergencies. The evidence here point to a gradual and sporadic production of New Testament texts. This would fit in with a theory that writing was a secondary aspect of apostolic ministry. If Pastor Sumpter’s theory is valid then one has to ask: Why did the Apostles wait twenty to forty years to begin writing canonical texts?

Another problem with Sumpter’s theory is that so few of the Twelve wrote canonical materials. Where are the writings of Apostle Thomas? I would love to read his account of Jesus’ death and resurrection. Where is the writing of Apostle Peter’s younger brother Andrew? And where are the writings of Thaddeus, Nathaniel, Philip, and the others? Why is it that we don’t have their written testimony to the Good News of Christ?

We need to take into consideration the small number of New Testament authors. From the Apostle Peter we have Mark’s Gospel and Peter’s two letters. We have from the Apostle John the Gospel that bears his name, three letters, and Revelation. We have Matthew’s Gospel and nothing else from him. Then we have the Gospel authored by Paul’s companion, Luke, who also authored the book of Acts. From the Apostle Paul we have a collection of a dozen letters. Hebrews has been traditionally attributed to Apostle Paul. This comes to a total of four apostolic composers of the New Testament corpus. Why so few? Where are the others? That is a question that raises doubts about Toby Sumpter’s theory.

For an Orthodox Christian the small number of composers of the New Testament corpus is not a problem. The Apostles were busy proclaiming the Good News of Christ, leading the early liturgies, and ordaining elders (Acts 6:2, 13:1-3, 14:23). From time to time they would write a letter if the occasion called for a written response but writing was not a core function of an Apostle, preaching was.

An Exaggerated Problem

Pastor Sumpter sketches what he purports to be a “popular theory” that he will refute.

A popular caricature of the process of canonization (a somewhat problematic phrase in its own right) is that tons of early Christians wrote tons of stuff and that it was only after the deaths of the first generation of Christians or so) when the subsequent generation of Christians suddenly woke up and began scrambling to collect as many meaningful looking scraps as they could find, like grabbing flecks of confetti blowing around in the wind. And the Holy Spirit led the Church to find all the right pieces and paste them all together just right (Emphasis added).

And,

. . . which I summarize as: The complete canon of Scripture was not determined until centuries after the apostles, and the Church (led by the Holy Spirit) determined what the canon of Scripture was. Therefore, the Scriptures derive their authority from the Church.

While a fascinating theory, it’s one I never heard of. It would help if Pastor Sumpter had referenced his sources for this theory. Perhaps Pastor Sumpter’s “caricature” is really only “popular” in certain select small Protestant splinter groups? Should we not favor the more widely accepted understanding that there was widespread reception of Paul’s letters and the four Gospels early on followed by a more gradual and contested reception of James, 2 Peter, Hebrews, and Revelation, combined with the eventual exclusion of disputed but popular texts like the Shepherd of Hermas and 1 Clement. This understanding of canon formation is similar to F.F. Bruce’s explanation which reflects the overwhelming mainstream of New Testament scholarship. (See link.)

Just as important is the mechanism by which canon formation took place. F.F. Bruce points out that it was not by means of a formal list that canon formation happened. He writes:

One thing must be emphatically stated. The New Testament books did not become authoritative for the Church because they were formally included in a canonical list; on the contrary, the Church included them in her canon because she already regarded them as divinely inspired, recognising their innate worth and general apostolic authority, direct or indirect.

He notes that the canon list created in the North African synods, Hippo Regius (393) and Carthage (397), did not impose something new on the churches but rather codified what had already been a general longstanding practice.

A Very Interesting Theory

Pastor Sumpter draws on E. Randolph Richards’ theory of how the New Testament canon came about. Richards notes that it was a widespread practice for ancient writers to keep on hand copies of their correspondence. Then he speculates that the New Testament canon was completed when Peter and Paul ended up in Rome before their martyrdom. Sumpter summarized Richards’ theory as follows:

Given the fact that Peter ended up in Rome at around the same time as Paul, and Luke is there already with Paul, and Mark is on his way (2 Tim. 4:11), we have all the indications that one of the first apostolic New Testament canon committees was holding session there in Rome in the mid 60s A.D. And if all that weren’t enough, don’t forget the fact that Peter refers to Paul’s letters as Scripture right around the same time (2 Pet. 3:15-16). In other words, the apostles knew what they were doing.

Add in John’s gospel, letters, and apocalypse, and we’re there. (Emphasis added.)

I don’t know what Toby Sumpter means by “we’re there” but I can tell you that it does not mean that he has proven his case! All he has done is sketch out an internally consistent hypothesis that awaits supporting evidence. What evidence is there that Peter and Paul were in Rome at the exact time in the mid 60s? And that Peter and Paul actually collaborated on finalizing the New Testament canon? And if he wants to really make his case, show how Hebrews and James came to be included in the New Testament canon in Rome in the mid 60s. What we have here is an interesting – if not a self-serving speculation? – theory that awaits solid evidence. This is far removed from the accepted mainstream of biblical scholarship.

Is the Muratorian Canon a List?

When we look closely at the Muratorian Canon (dated back to AD 170), what we find is not so much an authoritative listing of apostolic writings (which is what we would expect according to Pastor Sumpter’s theory) but an attempt to describe the books accepted by the early Church. What is striking about the Muratorian Canon is evidence that point to a traditioning process. In line 71 reference is made to the apocalypses of John and Peter being received:

We receive only the apocalypses of John and Peter, though some of us are not willing that the latter be read in the church. (tantum recipimus quam quidam ex nostris legi in eclesia; lines 71-72) (Emphasis added.)

The rather puzzling phrase that “some of us” were reluctant to have Peter’s apocalypse being read in church point to the autonomy of the local bishop and their liturgical authority. And in line 81 we read that nothing from heretical writers like Arsinous, Valentinus, or Miltiades ought to be received by the churches.

… which cannot be received into the catholic Church – for it is not fitting that gall be mixed with honey. (arsinoi autem seu valentini vel mitiadis nihil in totum recipemus; line 81). (Emphasis added.)

If Pastor Sumpter’s theory of canon formation held up, we would not be reading a lengthy description of books read out loud in the early Church. Rather, we would be reading a short succinct listing of titles and the assertion that this is a copy of an authoritative codex listing the Apostles Peter and Paul’s writings as proposed by Randolph Richards.

Did Irenaeus Use a Canonical List?

One of the earliest witnesses to the New Testament canon is Irenaeus of Lyons (d. circa AD 195). To combat the heretics Irenaeus defends the four-fold Gospel in Against Heresies 3.11.8-9 (ANF Vol. 1 pp. 428-429). He writes:

It is not possible that the Gospels can be either more or fewer in number than they are. For, since there are four zones of the world in which we live, and four principal winds, while the Church is scattered throughout all the world, and the “pillar and ground” of the Church is the Gospel and the spirit of life; it is fitting that she should have four pillars. . . .

The first thing to note is that Irenaeus takes the four-fold Gospel as an undisputed given. This points to an early development in canon formation with respect to the Gospel. Upon closer examination we find that Irenaeus gives us a lengthy description of the four Gospels. This is significant because he does not appeal to an official list of canonical Scripture which is what we would expect if Toby Sumpter’s theory held up. The formal listing represents a later stage of canon formation. In the early days of the Church the transmission of Scripture was part of a traditioning process. Irenaeus writes:

For if what they [the heretics] have published is the Gospel of truth, and yet is totally unlike those which have been handed down to us from the apostles, any who please may learn, as is shown from the Scriptures themselves, that that which has been handed down from the apostles can no longer be reckoned he Gospel of truth (AH 3.11.9, ANF p. 429; emphases added).

[Note: the Latin original has “ab Apostolis nobis tradita sunt” and “ab Apostolis traditum est veritatis Evangelium.” (Bold added) Source]

One important element in Pastor Sumpter’s argument is the notion that the production of written apostolic texts lay at the core of the Great Commission project. This implies that missionizing without written Scripture would be gravely deficient but this is not what we find in Irenaeus.

To which course many nations of those barbarians who believe in Christ do assent, having salvation written in their hearts by the Spirit, without paper or ink, and, carefully preserving the ancient tradition . . . .

Those who, in the absence of written documents, have believed this faith, are barbarians, so as regards our language; but as regards doctrine, manner, and tenor of life, they are, because of faith, very wise indeed . . . . (AH 3.4.2; ANF p. 417; emphases added)

It is important for Protestant readers to recognize that Irenaeus was not denigrating the importance of written Scripture but that his emphasis was on Apostolic Tradition in both written and oral forms. Irenaeus did not assume a tension between written and oral Apostolic tradition; nor did he assume a hierarchical ordering in which written tradition was superior to oral traditions. Rather he assumed written and oral Apostolic traditions to be complementary to each other.

Athanasius’ Festal Letter

In AD 367, almost two centuries after the Muratorian Canon and Irenaeus of Lyons, Athanasius the Great issued his annual Paschal (Easter) letter to the Diocese of Alexandria. It is here that we see the formal listing of canonical Scripture (NPNF Vol. IV, pp. 551-552). That Athanasius needed to distinguish between canonical and apocryphal books shows how much the early Church relied on the process of reception. This would not be the case if there had been a precise list from the start as would be the case in Pastor Sumpter’s theory. Evidence for the traditioning process can be seen in the way Athanasius described the reception of Scripture texts:

. . . . as they who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and ministers o the Word, delivered to the fathers; it seemed good to me also, having been urged thereto by true brethren, and having learned from the beginning, to set before you the books included in the Canon, and handed down, and accredited as Divine. (Letter 39, NPNF Vol. IV pp. 551-552; emphases added).

When we compare Athanasius’ approach to the biblical canon with early approaches we find a gradual transition from informal reception of Apostolic writings by local bishops to formal definition by the Church Catholic. Contrary to what Pastor Sumpter assumed, the early Church did not confer apostolic authority onto the New Testament texts; rather the early Church through its bishops recognized the New Testament texts as apostolic and rejected all others as spurious.

This raises serious concerns about Pastor Sumpter’s own theory and the purported problem that he seeks to address. Sumpter’s theory assumes a static listing of canonical scripture right from the time the Apostles Peter and Paul were alive. One, there is no evidence of such a hard and fast listing early on. What we do see is an early general consensus over the core of the New Testament with a few writings over which a general consensus would emerge centuries later. Two, there is no evidence for the “rival theory” that there was a blizzard of competing texts that forced church authorities to arbitrarily define as Scripture. Pastor Sumpter is welcome to defend his theory of canon formation by showing us the historical evidence that support his theory. What I have done is give an alternative theory of canon formation which is more in keeping with the general scholarship and is supported by evidence from the Muratorian Canon, Irenaeus of Lyons’ Against Heresies, and Athanasius the Great’s Festal Letter of AD 367.

Where’s the Bishop?

One missing element from Prof. Richards and Pastor Sumpter’s model of canon formation is the role played by early bishops. There’s no mention of the bishops at all in Sumpter’s article. This is a serious flaw given the importance of the bishop in early Christianity. Early bishops were ordained by the Apostles to lead the church and to preserve and pass on the Apostles’ teachings. They were tasked with preserving the Apostolic teaching whether in written or oral form. In the early days, the bishop had the authority to determine what would be read as Scriptures in the Sunday liturgy.

The apostolic basis of the early episcopacy explains the quick acceptance of the Petrine and Pauline corpus of the New Testament. As disciples of the Apostles the bishops were able to distinguish genuine apostolic teachings from heretical counterfeits. The need for synods where bishops gathered to decide on Hebrews, James and 3 John point to the importance of the early Church being guided by the Holy Spirit in the reception of these texts. What we do not find in the early sources is a top-down imposition of a canonical list. What we find are bishops gathered in synods seeking to reach a consensus as to what was apostolic.

Conclusion

This lengthy response is warranted by Toby Sumpter’s theological agenda – to prove that sola scriptura was part of early Christianity and not a late sixteenth century Protestant invention. Pastor Sumpter’s article is regrettably rife with guesswork, inference, and surmise. What we have found in our review of his article is an elaborate theory lacking in evidence. Given the lack of supporting evidence, the best thing for Pastor Sumpter is to admit that sola scriptura is a sixteenth century Protestant innovation. It represents a new approach to doing Christian theology that breaks from historic Christianity.

In contrast to Toby Sumpter’s speculative approach, I have taken an evidence based approach showing that the formation of the New Testament canon cannot be understood apart from the traditioning process. Evidence have been presented from Scripture, the church fathers, and church history for the Orthodox understanding of the New Testament canon formation, that is, through the traditioning process. The Orthodox Church through its bishops can trace its lineage back to the original Apostles. Through the past two millennia the Orthodox Church has faithfully preserved the physical text of Scripture as well as the right interpretation of the Scripture.

The debate over canon formation is far from a trivial matter. Canon formation requires an apostolic Church, a Church where its leaders have been ordained by the Apostles and their successors, and have in their possession Scripture through the traditioning process. Protestants lacking this historical traditioning process end up bootlegging sacred Scriptures.

Robert Arakaki

References

Athanasius the Great. “Festal Letter XXXIX.” NPNF Vol. IV, pp. 551-552.

F.F. Bruce. “The Canon of the New Testament” in Bible-Researcher.com

Irenaeus of Lyons. Against Heresies. ANF Vol. I.

“The Muratorian Fragment.” Bible-Researcher.com

E. Randolph Richards. 1998. “The Codex and the Early Collection of Paul’s Letters.” Bulletin for Biblical Research 8 (1998) 151-166.

Recent Comments