Book Review: Early Christian Attitudes toward Images by Steven Bigham (4 of 4)

This blog posting is a continuation of three earlier reviews of Father Steven Bigham’s book. In this posting I will be reviewing and interacting with Chapter 4: “Eusebius of Caesarea and Christian Images.”

Eusebius is famous for his Church History (Historia Ecclesiastica) which chronicles the history of Christianity from the time of Jesus to Constantine’s recognition of Christianity.

Bigham devotes a chapter to Eusebius because his outstanding reputation as a church historian. Eusebius’ Church History constitutes an importance source for what we know about early Christianity in general and about the attitudes of early Christians towards images in particular. Bigham also gives Eusebius attention because of his close association with Emperor Constantine. Constantine’s issuing the Edict of Milan in 313 marked the Church’s transition to an established public institution and the emergence of a Christian society.

Despite his fame as a church historian, Eusebius was nonetheless a controversial figure. He sided with the Arians and opposed the Council of Nicea (325). With respect to the icon controversy both sides appealed to Eusebius. Eusebius was appealed to at the iconoclastic 754 Council of Hieria. One of the leading defenders of icons in the eighth century controversy, John of Damascus, cited Eusebius in support of icons.

Eusebius as Pro-Icon

Eusebius discussed the statue of Christ and the woman with a hemorrhage at least three times: twice in his Church History (Chapters 7 and 18) and once in his Commentary on Luke (see Note 6, p. 189). We read in Church History 7.18:

1. Since I have mentioned this city I do not think it proper to omit an account which is worthy of record for posterity. For they say that the woman with an issue of blood, who, as we learn from the sacred Gospel, received from our Saviour deliverance from her affliction, came from this place, and that her house is shown in the city, and that remarkable memorials of the kindness of the Saviour to her remain there.

2. For there stands upon an elevated stone, by the gates of her house, a brazen image of a woman kneeling, with her hands stretched out, as if she were praying. Opposite this is another upright image of a man, made of the same material, clothed decently in a double cloak, and extending his hand toward the woman. At his feet, beside the statue itself, is a certain strange plant, which climbs up to the hem of the brazen cloak, and is a remedy for all kinds of diseases.

3. They say that this statue is an image of Jesus. It has remained to our day, so that we ourselves also saw it when we were staying in the city. [Emphasis added]

Apparently the statue of the miraculous healing was a popular pilgrimage site. From the phrase “remained to our day” it can be inferred that the statue was not a recent manufacture but had long been existence in Eusebius’ time. I speculate that the statue might date back to the first century but was disguised as a shrine to the god of healing, Aesclepius. [This notion is not farfetched. The secret Christians of Japan would conceal images of Mary or the saints within the Buddha image as a way of preserving their faith in a hostile society.] The statue’s popularity among early Christians and Eusebius’ positive tone runs against Protestant iconoclasm.

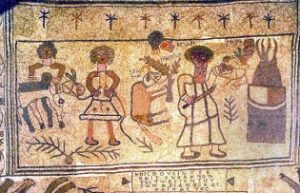

In his Proof of the Gospel Eusebius mentioned that in his time one could visit Mamre, the site of Abraham’s hospitality to the three visitors, and see the terebinth (shrine) of that famous biblical event (Genesis 18). Eusebius wrote:

And so it remains for us to own that it is the Word of God who in the preceding passage is regarded as divine: whence the place is even today honored by those who live in the neighborhood as a sacred place in Honor of those who appeared to Abraham, and the terebinth can still be seen there. For they who were entertained by Abraham, as represented in the picture, sit one on each side, and he in the midst surpasses them in Honor (The Proof of the Gospel l V:9 in Bigham pp. 210-211; emphasis added).

Eusebius did not indicate that this was an exclusively Christian pilgrimage site. It is possible that this was a popular pilgrimage site for Jews and that the Christians saw Christological significance in the person seated in the middle.

In his Life of Constantine 3.3 Eusebius described how Emperor Constantine ordered a huge mural displayed on the front portico of his palace showing a cross directly over the Emperor’s head and an impaled dragon under him. Eusebius’ admiration for this image runs contrary to the iconoclasm of his alleged letter to Constantia.

Even more striking is Eusebius’ description of Constantinople. Constantine desired that the new imperial capital be built free of any taint of pagan worship. Eusebius described in detail the New Rome in Life of Constantine 3.48 and 49:

And being fully resolved to distinguish the city which bore his name with special honor, he embellished it with numerous sacred edifices, both memorials of martyrs on the largest scale, and other buildings of the most splendid kind, not only within the city itself, but in its vicinity: and thus at the same time he rendered honor to the memory of the martyrs, and consecrated his city to the martyrs‘ God. Being filled, too, with Divine wisdom, he determined to purge the city which was to be distinguished by his own name from idolatry of every kind, that henceforth no statues might be worshipped there in the temples of those falsely reputed to be gods, nor any altars defiled by the pollution of blood: that there might be no sacrifices consumed by fire, no demon festivals, nor any of the other ceremonies usually observed by the superstitious. (Book 3.48)

On the other hand one might see the fountains in the midst of the market place graced with figures representing the good Shepherd, well known to those who study the sacred oracles, and that of Daniel also with the lions, forged in brass, and resplendent with plates of gold. Indeed, so large a measure of Divine love possessed the emperor’s soul, that in the principal apartment of the imperial palace itself, on a vast tablet displayed in the center of its gold-covered paneled ceiling, he caused the symbol of our Saviour’s Passion to be fixed, composed of a variety of precious stones richly inwrought with gold. This symbol he seemed to have intended to be as it were the safeguard of the empire itself. (Book 3.49; emphasis added)

Constantine’s attempt to commemorate the bravery of the martyrs and his celebration of Christ’s Passion is far removed from the iconoclasm and austere simplicity of Reformed worship. In fact the lavishness described by Eusebius’ bears a much closer resemblance to what we see in Orthodox churches today! Constantine’s appropriation of the arts represents, not a break from Christian Tradition, but rather its extension into Roman culture and public space. This leads Bigham to write:

Do we not have here the very principle of Christian iconodulia: the distinction between an idol and a Christian image, that is, an art consecrated to idolatrous worship and an art that has been purified of idolatry and used to proclaim the Gospel? (p. 201)

It is important to note that in all the pro-icon evidence presented by Steven Bigham not one described the use of image in early Christian worship. It would not be a stretch to say that Eusebius’ writings support the pro-icon position. But it would be a much bigger stretch to claim that Eusebius’ writings support the iconoclastic position.

Eusebius as Anti-Icon

Eusebius’ reputation as an iconoclast comes from a letter he supposedly wrote to Constantine’s half-sister, Constantia. In response to her request that he send her an image of Christ Eusebius scolds her for making such a request. The first mention of this letter was at the iconoclastic council of Hieria in 754 (p. 193). The iconoclastic tone of this letter is unmistakable but the letter raises more questions than it answers. If Eusebius held to a rigorist interpretation of the Second Commandment then how do we make sense of the positive tone in his Church History and elsewhere? The letter becomes even more problematic if dated not at the end of Eusebius life but in the middle of his literary career.

In his assessment of Eusebius’ iconophobia Bigham notes that the evidence is quite problematic (see pp. 193-199). One problem is that the sole evidence consists of one letter set against a whole array of pro-icons statements. Bigham notes that it is possible that Eusebius underwent a change of mind but this would entail a double change of mind, something highly unlikely and demands more evidence than is available. Another possibility is that Eusebius concealed his iconoclasm in the face of Constantine’s enthusiastic iconodulia, but this founder in the face that Eusebius’ correspondent was the emperor’s half-sister. Bigham notes that the simplest solution to this knotty conundrum is to exclude the Letter to Constantia from the Eusebeian corpus (p. 207).

Overall Assessment

Father Steven Bigham’s book makes an important contribution to our understanding of early Christian attitudes to images. Its value lies in the wide ranging survey of early sources up to Constantine. In terms of the recent debate between Reformed and Orthodox Christians Bigham does a commendable job showing that the historical evidence does not support but rather challenges the iconoclast presupposition that early Christians were either aniconic or were universally hostile to icons. Furthermore, the historical evidence points to iconoclasm as a minority position. This then points to the use of icons as part of the historic Christian and not some innovative add on as some claim it to be. That icons are part of the historic Christian Faith mirrors the Orthodox position on icons.

I found the book oddly structured. The third chapter on Christian attitudes before Constantine was over a hundred pages long while the next chapter was relatively short, about twenty pages long, and focused on one particular individual, Eusebius. Going from one long chapter dealing with a three centuries long period to a chapter focusing on one individual, and ending abruptly with no summary chapter, the book leaves the reader hanging in mid air.

The unevenness of Bigham’s treatment of the evidence is further accentuated by his omitting Epiphanius of Salamis. While understandable in light of Bigham’s promise that he would devote an entire book to Epiphanius, it does leave the reader with an incomplete picture of how early Christians viewed images. Note: In 2008, Bigham came out with: Epiphanius of Salamis: Doctor of Iconoclasm? Deconstruction of a Myth.

While there is much to commend about Bigham’s book, the reader should be mindful of the book’s limitations. One is that it does not cover the iconoclastic controversy in the eighth and ninth centuries. Another is that Bigham did not explore in depth the theological issues underlying the icon controversy. For a more comprehensive historical overview combined with a discussion of the theological issues involved I recommend Leonid Ouspensky’s two volume Theology of the Icon (1992) (Vol. 2). Another highly recommended book is Jaroslav Pelikan’s Imago Dei (1987).

Recent Comments