Review: Participatio – Centennial Volume 4: T.F. Torrance (2013)

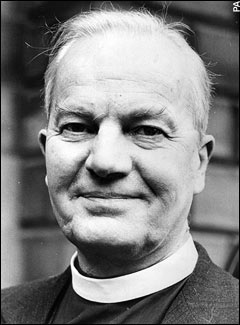

Thomas Forsyth Torrance, 1913-2007, commonly known as TF Torrance, was a Scottish Presbyterian theologian. He served as Professor of Christian Dogmatics at New College, Edinburgh, University of Edinburgh. He is widely known for his pioneering works on science and theology. He also played a key role in the theological dialogues between the Reformed and Orthodox communities.

In 2013, the Thomas F. Torrance Theological Fellowship published a centenary issue of Participatio marking the occasion of Torrance’s birth. The issue comprises a mix of personal reflections by those who knew him, some scholarly articles on aspects of his theology, correspondences between Torrance and Orthodox theologian Georges Florovsky, and two essays by Torrance himself on Orthodoxy. This makes for an especially rich and complex set of materials for those who want to learn more about Torrance as well as coming to grips with his interactions with Orthodoxy.

I thank Matthew Baker for bringing this centennial edition to my attention. In this blog posting I will be reviewing Participatio with an eye to Reformed and Orthodox dialogue. The articles deal with important theological issues like: justification, the divine monarchia, the concept of energy, and Church Fathers like: Athanasius, Ephrem the Syrian, Cyril of Alexandria, Mark the Monk, and Maximus the Confessor. I will be discussing just a few of the articles published. It is hoped that will be further interactions by others with the other articles in the centenary issue.

TF Torrance and Theology

Probably the word that best describe Torrance’s theology is: versatile. He is widely known for his pioneering work in the study of theology and science as well as for his works in systematic theology. Unlike most Protestant theologians who favored systematic theology, Torrance preferred the historic dogmas of the Church. He did not hold to systematic theology because he believed that God was not “systematic” and because he felt systematic theology represented a holdover from the Scholasticism of the Middle Ages (Pelphrey pp. 56-57). In his classroom lectures Torrance was especially enthusiastic about three theologians: Athanasius, Calvin, and Barth! (Noble p. 15) Torrance’s admiration for Athanasius was such that he had an icon of Athanasius on prominent display in his office! (Dragas p. 32)

Torrance points to the broader element in the Reformed tradition. While some were hostile or suspicious of Barth’s theology, others like Torrance were receptive to it. He was also critical of certain elements of Reformed theology, at least of the Dutch variant.

On this occasion, a student had defended the doctrine of Limited Atonement, arguing that Christ died only for the elect and not for all. Torrance’s reply was devastating: “That Christ did not die for all is the worst possible argument for those who claim to believe in verbal inspiration!” (Noble p. 14)

Torrance’s rejection of limited atonement stemmed from his loyalty to the Scottish stream of the Reformed tradition and that particular tradition’s debate with “scholastic federal Calvinism” (Noble p. 15).

Torrance and Reformed-Orthodox Dialogue

Torrance was one of the rare Reformed theologians of the twentieth century who not only studied the early Church Fathers but also engaged in extensive conversation with Orthodox Christians. He was in frequent correspondence with one of the leading twentieth century Orthodox theologian, Georges Florovsky. The warmth of their friendship is evident in the letters published in the centennial issue (pp. 287-324). Florovsky regarded Torrance as one theologian that the Orthodox should give heed to (Dragas p. 34). Another one of Orthodoxy’s leading modern theologian, John Zizioulas, author of Being As Communion, once served as Torrance’s teaching assistant. In the course of his academic career Torrance got to know Orthodox Christians who would later become prominent hierarchs, e.g., Archbishop Methodios Fouyas, who arranged for Torrance to be given the title of “honorary protopresbyter” by the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Alexandria (Baker Note 81, p. 317).

During the 1970s Torrance worked hard to promote theological dialogue between the World Alliance of Reformed Churches and the Ecumenical Patriarchate. Despite his immense knowledge of Athanasius and other Church Fathers, Torrance apparently was unaware of how the Orthodox did theology. On this occasion Torrance wanted to draft a letter opening the way for Reformed dialogue with the Patriarch of Constantinople. Dragas recounted:

I replied: “Professor Tom, this will not fly. Let me go through it and explain why.” He listened to me for a half an hour without saying a word (!), while I went sentence by sentence through his memorandum. Among other things, I said: “No Orthodox would approve of this opposition between the Alexandrians and the Cappadocians – we do not see the Fathers this way. Likewise, when you first go to approach an Orthodox Patriarch to ask him for a dialogue, you should not come with criticisms about his Orthodox theologians and their theological tradition. Rather, you should first present your credentials as Christians and state that in faithful obedience to the will of Christ you approach the Orthodox with a wish to be reconciled. You need first to explain to them who you are, what you believe and practice as Reformed Christians, that you have ordained clergy and sacraments, synods and so forth, and what all these mean to you.” I also suggested that he give the patriarch a copy of the Reformed Prayer Book as a gift. He was baffled, and asked: “Which Prayer Book? Every Reformed Church has its own.” (Dragas p. 39)

I laughed when I read of Torrance’s bafflement. As a Reformed Christian who became Orthodox I can relate to both sides. The difference here is the ancient principle: lex orandi, lex credendi. Where for Reformed Christians a prayer book expresses what they believe, for the Orthodox the liturgical texts prescribes and regulates what they believe. For the Orthodox one cannot willy nilly change the prayer books because the liturgical services are part of the received tradition of the Church.

In the 1980s under Torrance’s leadership a number of Reformed-Orthodox dialogues were held culminating in the “Agreed Statement on the Holy Trinity” in 1991. But as Matthew Baker noted in his interview with Dragas the Agreed Statement seems to have been all but forgotten by the Orthodox. Dragas’ explanation (p. 41) as to why the Agreed Statement was short lived is educational for any who wish to engage in serious ecumenical dialogue between the Reformed and Orthodox traditions.

Florovsky wrote this frank appraisal of the prospects for unity in Torrance’s “Our Oneness in Christ and Our Disunity as Churches”:

It is our tragedy that we cannot travel beyond a certain narrow limit. It would not help at all if I, as it were, “pass” the document. It would not make it any more “ecumenical,” and somebody else will point it out. I am terribly disturbed that, being brethren and friends in the sacred name of Jesus, we cannot meet at His table. But the tragedy is that we cannot, simply and purely. Let us pray together and for each other, and do what we can do together, trusting in the mercy of the Lord. (p. 312)

TF Torrance’s career points to the potential for fruitful Reformed-Orthodox dialogue but it also points to the perils of pursuing ecclesial unity. This writer considers the former to be feasible but the latter unlikely.

Torrance on Orthodox Worship

Torrance was highly appreciative of the fact that Orthodoxy has preserved the ancient form of worship and warned Protestants against thinking that their simplified form of worship represented New Testament worship.

It would be a very great mistake for us Protestants to imagine that the way in which we worship God is a return to the simplicity of the New Testament – our Protestant worship is very far removed from the worship of the Early Christians which was grounded on a profound unity between the Old Testament and the New Testament. (Torrance p. 330)

No doubt the liturgy has become more elaborate through time, largely through further adaptations of the Old Testament ways of worship, but it remains essentially the same, and it is, I believe – let me say it quite frankly – still the most biblically grounded worship I know: grounded in the whole Bible. (Torrance p. 331)

Torrance took note of the constraints placed on Calvin that led him further away from the historic forms of worship.

Calvin himself did not know as much about the worship of the Early Church as we do, and unfortunately he allowed the mediaeval Jewish scholars to have too great an influence on his interpretation of the Bible so that he swept away many of the biblical forms of worship handed down from the Early Church. (Torrance pp. 331-332)

Torrance saw much value in the Orthodox liturgical tradition and sought to incorporate this into the Church of Scotland (Torrance p. 332). However, ressourcement is quite different from the traditioning process that is part of Orthodoxy. Where ressourcement allows the theologian considerable latitude as to which Church Father or teachings may be incorporated into their theological system, the traditioning process is much more constricted — the bishop or priest commits himself to following Holy Tradition as it has been transmitted from the Apostles.

“The Relevance of Orthodoxy”

Careful reading of Torrance’s essay “The Relevance of Orthodoxy” (pp. 324-332) shows points of contact and differences. Torrance understood the Nicene Creed as emerging from the early Church’s exegesis of Scripture. This strikes me as a rather Protestant approach, understandable in light of his church background, but at odds with Orthodoxy. Torrance wrote:

The Nicene Creed was distilled, as it were, through careful exegesis of the Scriptures, in order to find a basic and accurate way of expressing those essentials of the Christian faith, apart from which it cannot remain faithful to the Gospel. Hence in the tradition of the Orthodox Church the Nicene Creed has the effect of throwing the mind of the Church back upon the Holy Scriptures, and making them central in all its worship, doctrine, and life. (Torrance p. 326)

I would argue that the Nicene Creed emerged out of the interaction between the regula fidei (rule of faith) handed down by the bishops and the Church’s reading of Scripture, that is between oral tradition and written tradition. I noticed that Torrance made no mention of oral tradition in his essay. This is a significant omission because it is in oral tradition that the sense of Scripture is preserved. If one looks at the early patristic writings, e.g., Irenaeus of Lyons, one finds that the rule of faith (creed) was derived from oral tradition, not from Scripture (Against Heresies 1.10.1). Without this sense of the inner meaning obtained from oral tradition, the Scriptural text becomes susceptible to unconventional and even deviant interpretations that stray far from what the Apostles had in mind in the first place.

I also find it striking that Torrance had little to say about the episcopacy and the magisterium (teaching authority) of the bishop. This oversight becomes even more apparent when I read what he had to say about the Filioque clause; the clause that bedeviled church relations for a thousand years to this day.

There is a difference between the Eastern and Western forms of the Nicene Creed, for the Western Church speaks of the Spirit as ‘proceeding from the Father and the Son’ whereas the Eastern Church speaks of the Spirit only as ‘proceeding from the Father’, but actually the Eastern Church thinks of that as taking place through the Son, not as through the Church. Thus in spite of the different formulations of the East and the West the Eastern Church is more Christological and preserves the Mystery of the Spirit in a way that is so often lost in the West. One of the effects of the Orthodox doctrine of the Spirit is found in the way in which they regard the structures of the Church’s life and thought as open structures, shaped by the mystery of Christ and open to the transcendent Majesty and Lordship of God. (Torrance p. 328)

Torrance understood the Nicene Creed descriptively, not prescriptively, that is, it articulates the theological consensus of the Christian community. In significant contrast the Orthodox understand the Nicene Creed to be binding on all Christians because it was promulgated by an Ecumenical Council which represents the Church guided by the Holy Spirit. This is because at the Council of Nicea the bishops exercised their magisterium as a collective body. Furthermore, as it was formulated and promulgated by an Ecumenical Council, no one, including the Bishop of Rome, has the authority to modify the Creed. Torrance’s silence with respect to the role of the bishops’ magisterium in the Nicene Creed is quite revealing to Orthodox Christians. So, as much as Torrance is sympathetic to the Orthodox Church’s position, he does not seem to get it at certain significant points of doctrine and polity.

Cyril of Alexandria and Justification

Donald Fairbairn’s article “Justification in St. Cyril of Alexandria, With Some Implications for Ecumenical Dialogue” (pp. 123-146) is an attempt to flesh out one of Torrance’s insight. Torrance once noted that Cyril of Alexandria was the best expositor of the Evangelical doctrine of justification by grace but made no attempt to elaborate on that statement and so the task of doing so fell on Fairbairn’s shoulders (p. 124).

The challenge here lay in finding in Cyril the Protestant understanding of justification as a passively received righteousness and sanctification as a cooperatively produced holiness/righteousness (Fairbairn p. 126). This distinction is key to Protestant theology. In light of the fact that Cyril conflates justification with sanctification it has been inferred that he is advocating an active works righteousness that the Reformers strenuously opposed. Fairbairn argues that what Cyril had in mind was that justification and sanctification were both created by God in the believer as a result of the believer’s union with Christ (Fairbairn p. 127).

Using the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae search engine Fairbairn was able to gather data about Cyril’s understanding of justification. What he found was the overwhelming use of the passive form (Fairbairn p. 128). Cyril’s understanding justification and sanctification as passively received is based on his understanding of the Incarnation. Fairbairn notes,

It is that God the Son became human precisely so that he, God, could do as man something for human beings that we could not do for ourselves. This Christological emphasis dovetails closely with the idea that Christ gives the believer a righteousness from without. For Cyril, even the human side of salvation is not primarily our human action; it is Christ’s human action. In order for that human action to accomplish our salvation, it had to be human action performed by God the Son. (p. 142; italics in original)

I very much appreciate Fairbairn’s even handed conclusion. He noted the even with the strong similarities between Cyril and Protestantism (justification as passive) differences remain (Cyril’s failing to distinguish sharply between justification and sanctification) (p. 142). Especially striking is Fairbairn’s statement that justification was not central to Cyril’s soteriology (p. 142). I appreciate the irenic tone in Prof. Fairbairn’s challenge to both Protestants and Orthodox.

As a result, I suggest that a deeper consideration of Cyril’s doctrine of justification can both challenge Protestants and the Orthodox, and help to uncover latent common ground between them. Protestants need to recognize that justification is not merely or even mainly transactional, but primarily personal and organic. We are united to Christ as a person, and as a result, his righteousness is imputed to us. The forensic crediting of righteousness grows out of the personal union. (p. 144)

The concept of “justification by faith” is something shared by both Protestants and Orthodox but they diverge with respect to their understanding of what justification is and how it applies to the Christian. Prof. Fairbairn’s approaching “justification by faith” via patristics is promising. It should be kept in mind though that Cyril is just one Church Father among a whole range of other Church Fathers.

The Divine Energies

Stoyan Tanev’s article “The Concept of Energy in TF Torrance and Orthodox Theology” (pp. 190-212) touches on the Essence-Energy distinction, a subject that sets Western theologians and Torrance apart from the Orthodox. The issue of our ability to come to knowledge of God came to forefront in the Hesychast controversy. Palamas wrote that while God is unknowable in His Essence, we can know God through his Energies. Barlaam rejected the Hesychasts’ claim that our bodies and our minds can be transfigured by the divine light. At the Great Councils of Constantinople in 1341 and 1351, the Orthodox Church affirmed Gregory’s distinction between the Divine Essence and Energies making it a dogma of the Orthodox Church (Tanev p. 193). This controversy is not one familiar to many Protestants. But, nonetheless, from this controversy came positions and insights that can help deepen the Reformed understanding of God and the Trinity. Tanev’s essay is helpful in that it approaches Torrance from the standpoint of theology, patristics, and modern science.

Torrance did not hold to the Essence-Energy distinction (p. 193). One of his constant concerns was guarding against a dualism that sets theology against economy (pp. 194-195). Tanev notes that Torrance did not quite grasp the later Byzantine theology which resulted in the constraining of his understanding to the pre-Chalcedonian legacy of Athanasius and Cyril (p. 202).

One fascinating aspect of Tanev’s essay is his discussion of how Torrance’s understanding of space shaped his theology. Tanev criticized Torrance’s for his narrow understanding of science, e.g., he embracing Einstein while rejecting quantum theory (pp. 204-205). Torrance’s commitment to realism prevented him from embracing Bohr’s quantum theory which posited that a quantum object might possess complementary energetic manifestations that depended on the circumstances of the interaction between the observer and the object (pp. 206-207). One notable contribution in quantum physics is the discovery that there is no simple objective study of physical phenomenon; “observed reality can be transformed by the fact of observing it.” (p. 207) This gives physical reality a dynamic and probabilistic character much like “the freedom of interpersonal human relations” (p. 209). Tanev saw Torrance’s failing to draw on the epistemological implications of quantum theory as contributing to his lacking a proper understanding of hypostasis (p. 208; 210-211). As a corrective to Torrance’s realism, Tanev presents Christos Yannaras who appropriated Einstein and Bohr to explicate John of Damascus who saw physical space as a locus of the disclosure of God’s personal energy (p. 210).

The distinction between the nature and the energies of God, without denying the reality of the natural distance of God from the world, preserves the world as a space of the immediate personal nearness of God and manifests God as the place of the universe: “For God is not contained, but is himself the place of all.” (p. 210)

Torrance’s attempt to integrate theology with modern physics has yielded some interesting insights. Tanev shows how quantum physics can lend support for the Orthodox approach to describing the Trinity. Admittedly, this is a rather novel theological method for Orthodox Christians. Tanev’s article is an example where the methodology of Western systematic theology can lead to interesting insights.

Torrance and Zizioulas on the Divine Monarchia

Dragas’ explication of how Torrance and Zizioulas understood the Trinity differently is both fascinating and insightful (pp. 43-45). Torrance preferred to emphasize “the monarchy of the entire Trinity instead of the unique monarchy of the Father.” This means that “the Trinity as revealed in the economy is wholly identical with the essential Trinity in eternity” (p. 43). This position aligns Torrance with Barth, Rahner, and other Western theologians but against the Eastern theologians who insist that in the economy God does not reveal his Essence, but instead is revealed as Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit through his energies (p. 43). Torrance’s suspicion of drawing a distinction between God as Being and Act made him suspicious of the Cappadocian Fathers who insisted on the Monarchy of the Father as the best approach to understanding the Trinity.

Nikolaos Asproulis’ “T.F. Torrance and John Zizioulas on the Divine Monarchia: The Cappadocian Background and the Neo-Cappadocian Solution” (pp. 162-189) is an important essay given Torrance’s rejection of the Cappadocian teaching on the monarchy of God the Father. This constitutes one of the biggest differences between Torrance and Orthodoxy for all his sympathies for Orthodoxy. In his approach to patristics Torrance was fascinated with one particular figure, Athanasius the Great, and with two concepts: homoousios and perichoresis.

In this essay Asproulis compares Torrance against one of Orthodoxy’s leading modern theologian, John Zizioulas. Asproulis notes that what sets Zizioulas apart was the fact that he did not approach the Church Fathers in terms of the historical study of texts but favored a more systematic exploration of theological concepts. This is an example of an Orthodox theologian benefiting from the Western theological method. Asproulis draws attention that something of a paradigm shift took place when the Cappadocians began assigning an ontological reality to the term “prosopon” which up till then simply meant “a mask worn by actors” (pp. 166-167).

In this light, the Eucharist renders possible the participation by communion in the very life of God, which is communion of persons caused by the person of the God the Father. In Zizioulas’ understanding, this communion legitimates discussion about God’s very being, the question of how God is – his personal mode of existence – rather than the what of the ineffable divine ousia. Where Torrance took as his starting point the economic self-manifestation of God in Christ, Zizioulas took a meta-historical approach beginning with doxological formula: Glory be to the Father, with the Son, and with the Holy Spirit (p. 168).

Asproulis notes that where the starting point for Torrance’s theology was the narrative of biblical revelation, for Zizioulas it was the Eucharistic experience of the early Christians (pp. 181-182). He notes that Zizioulas’ theological method leads to a diminishment of the unity between theology and economy (p. 182). Asproulis criticize both Torrance and Zizioulas for having too narrow a patristic base for doing theology: Torrance for relying almost exclusively on Athanasius and Zizioulas on the three Cappadocians (p. 183).

What makes Asproulis’ essay especially valuable for Reformed-Orthodox dialogue is his presenting an excerpt from Gregory of Nazianzus’ Fifth Theological Oration 31.14 on the divine monarchia that was read by Torrance and Zizioulas in different ways (p. 186). Asproulis then brings to our attention Gregory’s Oration 42.15 and uses this to criticize both Torrance and Zizioulas (p. 187). What is to be appreciated about Asproulis’ essay is his attempt to assess the theological differences of two great ecumenical thinkers of the twentieth century on the methodological level.

An Assessment

This centennial edition will be valuable for students of TF Torrance’s thought who want to better understand Torrance’s understanding of the Trinity and his engagement with the Church Fathers. It will also be valuable for those interested in Reformed-Orthodox dialogue. Baker notes:

As readers of this volume will discover, not everything Torrance had to say is acceptable to the Orthodox. The disagreements are real, and they are not trifling. But the affinities also are significant, and the mutual respect is profound. Orthodox theologians still have much to gain from Torrance on multiple fronts: his creative and forceful presentation of Athanasian-Cyrilline Christology, most especially regarding the high priestly work of Christ; his re-articulation of patristic hermeneutics and rigorous treatment of theological epistemology in response to modern challenges; and his patristic-inspired forays into theology-science dialogue. (p. 7)

In my opinion TF Torrance’s biggest contribution towards Reformed-Orthodox theological dialogue took place in his role as a professor and mentor to various Orthodox Christians. It is thanks to him that we can benefit from the superb scholarship of Andrew Louth and John Zizioulas. Personal relationships across theological traditions are especially beneficial. This can happen at the advanced graduate level where strong personal ties are often forged in the course of advanced theological studies.

There are two common grounds that the Reformed and the Orthodox share: Scripture and the Church Fathers. Grounding Reformed-Orthodox dialogue in these two areas would be a good starting point. I would venture that one arena where Reformed and Orthodox dialogue can be advanced is in the academy in disciplines like theology.

The contributions made in this edition of Participatio shows the fruits of interaction between Orthodox and Reformed on issues like the divine Monarchy, the concept of Divine Energy, the Persons of the Trinity, Incarnation, etc. There is much potential in the interaction between Orthodoxy’s grounding in patristics and the Reformed grounding in dogmatics and systematic theology. The benefits of Western systematic theology are the rigor and disciplined thinking it brings to the field of theology. Absent intellectual rigor patristics and liturgics can easily end up in an unthinking traditionalism that uncritically reiterates the past. Journals like Participatio can play a strategic role in advancing Reformed-Orthodox dialogue by encouraging scholars to submit articles dealing with topics of interest across the two traditions and that endeavor to examine these topics using the theological methods from the two traditions.

As a theology professor Torrance put his focus on dogmatics rather than systematic theology. Torrance can serve as an example for other Protestant theologians to follow. It would help if Protestant seminaries were to offer theology classes ordered along the line of dogmatics and patristics. This method is closer to the way Eastern Orthodox Christians do theology and would make initial contact and dialogue much easier. The systematic approach favored by Western theologians is alien to Orthodoxy and has often impeded Reformed-Orthodox dialogue.

One of Torrance’s greatest shortcomings was his failing to understand or take seriously the conciliar nature of Orthodox theology. This failing seems to apply not just to Torrance, but to other Protestants as well. To put it simply, Reformed theologians do theology textually, that is, they read the text (Scripture or the Church Fathers), extract data, then proceed to organize and coordinate the data into coherent theological systems. Orthodox theologians do theology ecclesially, that is, they seek to articulate what the Church has taught and confessed through its worship and through its councils. Until Protestants grapple with the ecclesial and conciliar dimensions of doing theology, theological dialogue between Reformed and Orthodox Christians will be hampered by misunderstandings and people speaking past each other.

Protestant theologians need to engage in a critical scrutiny of theological methods, both theirs and those outside the Protestant tradition. For example, Reformed Christians need to discuss with the Orthodox the importance of the Ecumenical Councils and the patristic consensus for doing theology. Also, they will need to discuss with Orthodox Christians the implications of Christ’s promise to send the Holy Spirit in John 14:26 for the role of the Church in doing theology. By bringing to light some basic differences between the Reformed and Orthodox traditions, these questions can facilitate and open and honest interfaith dialogue.

TF Torrance’s eagerness to engage Orthodoxy presents a model for other Reformed Christians. All too often one finds Reformed theologians who are quick to stereotype Orthodox Christianity or who fail to read the Church Fathers in their historical context. Given the fractured state of Protestantism and the plurality of Protestant theologies, there is much to be gained from engaging Orthodoxy’s ancient theological and spiritual heritage. Orthodoxy offers the Reformed theologians a means of accessing the Church of the early Church Fathers and Ecumenical Councils. If Reformed and Orthodox theologians can interact with each other using theological methods that integrate biblical exegesis with patristics, disciplined theological reflection, and sensitivity to ecclesial structures I am confident that the common ground between the two traditions will be broadened and deepened to the benefit of both sides.

Robert Arakaki

Note: I briefly touched on Torrance in one of my earlier postings: “Platonic Dualism in the Reformed Understanding of the Real Presence?”

See also a podcast by Fr. George Dragas’ Assessment of TF Torrance

Recent Comments