Rock and Sand: An Orthodox Appraisal of the Protestant Reformers and Their Teachings (2015)

Rock and Sand: An Orthodox Appraisal of the Protestant Reformers and Their Teachings (2015)

Review by David Rockett

When a seminary trained Protestant Pastor writes a book-long critique of Protestantism after converting to become an Orthodox Priest, it makes for interesting reading! However, critiques of theological systems and its primary proponents outside one’s own loyalties are on the surface suspect. Has the critic carefully understood what he proposes to critique? Is he fair or one sided? These are no small issues if the critique is to be taken seriously. Does the critic have the credentials and standing to do such a thing?

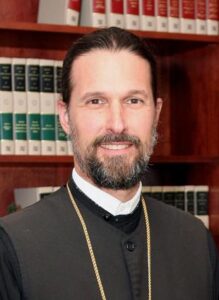

In this light Fr. Josiah Trenham is uniquely qualified to offer a compelling critique of the Protestant Reformers and their theology. Raised in a devout reformed Protestant family and Reformed church, Fr. Josiah was educated by the top Reformed intelligentsia. Fr. Josiah received his B.A. in Social Science or History from Westmont College in Santa Barbara, CA. His senior thesis was on the famous American theologian and revivalist Jonathan Edwards (1989). In 1992, he received his M.Div. from Westminster Theological Seminary, Escondido, CA, having studied also at Reformed Theological Seminary in Jackson, MS, and Orlando, FL under the Reformed theologians Drs. John Frame, John Gerstner, and R.C. Sproul. In 2004, he received his Ph.D. in theology from the University of Durham, England, studying under the well-known Orthodox Christian professor of patristics, Father Andrew Louth.

The hypothetical reverse would be a book-long critique of Orthodoxy’s leading Fathers lives and theology expressed in the Seven Ecumenical Councils – all in historic context, from a Reformed Ph.D. pastor who was raised as a cradle Orthodox, educated at an Orthodox university and seminary (Holy Cross?, St. Vladimir?) – but converted to Protestantism and received his Ph.D. from Westminster! Reformed-Orthodox dialogue would benefit from such a book. We pray our Protestant friends and theologians will read Fr. Trenham’s book with the same zeal an Orthodox would read such a hypothetical book! For now we are more than satisfied with Fr. Josiah’s book: Rock & Sand.

Introduction and Historic Context – Roman Catholic Europe 1500s

Father Josiah’s introduction gives us his book’s three-fold purpose:

…to provide the Orthodox reader with a competent overview of the history of Protestantism…to acquaint Orthodox and non-Orthodox readers with a narrative of the historical relationship between the Orthodox East and the Protestant West…[and] to provide a summary of Orthodox theological opinion on the tenets of Protestantism. (p. 2)

Before doing this he sets the context for the Reformation: “The Protestant Reformation cannot be understood without a cursory grasp of the political, social, cultural, and ecclesiastical developments that created 15th century Europe.” (p. 3) Given Fr. Josiah’s history degree this is understandable and critical for us Moderns. Too often we rush to debate theological tenets before grasping the context or the dominant cultural and sociopolitical realities of the time. Fr. Josiah notes: “The traditional western historiographic categories of ‘Dark Ages,’ ‘Middle Ages,’ ‘Renaissance,’ and ‘Reformation,’ have little meaning in the East, and in fact have now been widely discarded in Western academia. The Fall of Rome…was not as significant in the East…” (p. 5)

The city of Constantinople or New Rome thrived intellectually and politically for centuries long after old Rome had fallen.

Prior to the Reformation, the papal West entered into a scholastic period in which theology was conformed to philosophical paradigms and detached from its traditional ascetic milieu. Theologians became academics and bishops political lords. Detached from the Orthodox East and its insistence on patristic continuity, papal innovations – theological and practical – abounded. These innovations, advanced by a newly articulated and aggressive view of papal supremacy, were supported by a collection of forged historical documents known as the False Decretals…These forged papal letter were fabricated in order to place in the ever-growing claims of papal arrogance and supremacy into the mouths of early saint-popes and thus establish the papal novelties as ancient Christian faith. (pp. 5, 6)

Add to these the Donation of Constantine:

This falsified imperial decree is said to have been written by Emperor Constantine the Great to Pope Sylvester (314-335)…an enumeration of the privileges bestowed upon the pope and his successors. (p. 6)

Thankfully, an honest and influential German Roman Catholic churchman named Cardinal Nicholas of Cusa exposed these documents as fraudulent. Fr. Josiah notes:

Martin Luther was aware of Cusa’s work and obtained a copy as a young theologian, which certainly influenced his thinking on the proclaimed rights of the papacy. Their authenticity has been universally rejected for hundreds of years, even by the papacy. (p. 7)

Luther was not alone in noticing the papacy and their representatives’ moral duplicity, and willingness to lie for great wealth and power. Political power and wealth increasingly became issues surrounding the Reformation in every country including England and its ruler Henry VIII. Fr. Josiah concludes this section with:

A strong argument can be made that the Protestant Reformation itself was more a land grab by the Protestant princes than about ecclesiastical renewal, and that without their cooperation Martin Luther would have been a flame that quickly ignited, but then rapidly dissipated. (p. 8)

An Orthodox Appreciation of Protestant Virtues

This chapter on page 251 appears to be out of sequence. Had Fr. Josiah been writing primarily for a Protestant instead an Orthodox audience, I suspect this chapter would have occurred earlier. Anticipating many Protestant readers of this review I’ve put it here. The book at points is sharply critical of the Reformers and their doctrines, and Fr. Josiah’s graciousness in this chapter seems most fitting:

Before launching this exercise in Orthodox apologetics, however, which must by necessity be highly critical, I would like to share with you an exercise that I require my catechumens to perform in the catechetical program that seekers are asked to engage in. [A blank sheet of paper is given for them to divide in half, writing “Orthodox Beliefs” on the left column and “Heresies/Errors” on the right, make a list.]…The intention of this catechetical exercise is two-fold. First it raises the issue of heresy to the proper intensity. Heresy is not to be played with, and it certainly does not save. Christ, Incarnate Truth, saves. The theological divisions that afflict Christendom are extremely serious, and are not to be swept under the rug by naïve theological peaceniks who assume that, just because they do not understand theology, it therefore must be unimportant…On the other hand, this catechetical exercise guides the person in process of conversion to a deep appreciation of the good of their previous confession. (pp. 253, 254)

Over the next six and half pages Fr. Josiah highlights elements of Protestantism which should be deeply appreciated and given thanks for by converts to Orthodoxy. Listed here without Fr. Josiah’s commentary:

An exceedingly high value upon the text of Holy Scripture; zeal for missionary work…ability of Protestant Christians to articulate concisely…what Jesus Christ has done for them…they call ‘giving a testimony’; a deep and costly commitment to Christian education; aggressive commitment to cultural engagement with Christian values…[finally saying] “I could go on, but I think this is enough to understand that the Orthodox theological critique of Protestantism does not derive from blind prejudice, or a lack of appreciation of the virtues of Protestantism. I admire the virtues of Protestantism most sincerely and make myself its student in those areas where it is exceptional. (pp. 257-263)

Let us pray the critical aspects of the book will be understood in this light.

The Protestant Reformers

Martin Luther was educated as a lawyer at Magdeburg and Eisenbach and the Erfurt University (1501-1505). Yet, he had a near death experience during a lightning storm and prayed to St. Anne with an oath he’d become a monk if she saved him. He took solemn vows as an Augustinian monk in August 1505 at age 22, and was ordained a priest in 1507 at age 24. His father rode in for his first Mass with twenty riders and bestowed a generous gift of money to the monastery. Luther on his visit to Rome was scandalized by the debauchery and blasphemy committed by the priests there, and then later with the sale of indulgences. He posted his 95 Theses on 31 October 1517 just a few weeks before his 34th birthday. Fr. Josiah rightly points out these 95 Theses are no articulation of Protestant dogma, but objections to Roman Catholic innovations that any Orthodox could also agree with on principle.

We can certainly admire Luther’s courage before Rome as we do other early would be reformers like John Wycliffe. Yet we see here just the beginning of the theological controversy that would follow Luther for the rest of his life. Fr. Josiah writes:

The greatest of these [controversies] took place at the Colloquy of Marburg in 1529. This official gathering was designed to unify the Protestant theologians, but instead served to express the deepest of divisions between Luther and Swiss Reformer Ulrich Zwingli on the subject of the eucharist.” Luther thought his teaching on consubstantiation was the clear teaching of Scripture, and neither could understand why the other was being so hardheaded and disobedient to the ‘clear teaching of Scripture.’ The Marburg Colloquy and Protestant eucharistic controversy revealed the greatest weakness of the Protestant embrace of the doctrine of sola scriptura, and proved the absurdity of any dependence on the clarity of Scripture alone to establish common doctrines. Luther felt very deeply on this matter, and said ‘Before I would have mere wine with the fanatics, I would rather receive sheer blood with the pope. Accomplished Protestant leaders like Carlstadt, Zwingli, Oecolampadius in Basel and Bucer in Strasbourg disavowed Luther’s teaching on the sacraments and church polity. We Orthodox Christians are led to ponder: where is the reality of sola scriptura and the perspicuity of Scripture if even those bound by faculty, friendship, politics and faith cannot agree on the meaning of the central Christian act of worship? (pp. 36, 37)

The failure of Sola Scriptura to engender unity among the Reformers on the central sacrament of the Church is a major point Fr. Josiah makes several times in the book. Space prevents a look into Luther’s often violent rages against the Anabaptist movement he inspired, and the Jews he often seemed to loathe. Yet of the ascetic life and monastic estate Fr. Josiah takes careful note:

In his Small catechism Luther calls marriage ‘one hundred times’ more spiritual than the monastic estate. Yet to enter into the married estate himself Luther became an oath-breaker, as did his wife Catherine. As adults they had sworn oaths to serve Christ faithfully as celibate person like St Paul. Yet as adults they broke the oaths and encouraged hundreds of others to do likewise. In such a case of clear ethical violation Luther found it convenient to vilify the monastic estate in order to justify breaking his own vows. Yet his own Protestant prince, the elector Frederick, who consorted with concubines himself, was so opposed to this offense that Luther was not able to marry as long as Frederick lived. Luther’s colleague and friend Melanchthon was so opposed to Luther’s oath-breaking and marriage to Catherine that he himself did not attend the wedding. (p. 46)

More could be said here and Fr. Josiah reviews a history few Protestants are likely to know. In a footnote he comments further: “Luther was clear about how far from traditional asceticism he had strayed. ‘I now seek pleasure and take it wherever I can.’ He should not have wondered, after such attacks upon ascetical Christian practice, why he failed so bitterly to effect a moral improvement in Christian life amongst the Germans.” (p. 47)

Ulrich Zwingli was a Roman Catholic priest born in Switzerland a year after Luther. Fr. Josiah demonstrates he is far more the father of modern American evangelicalism than either Luther or Calvin.

Zwingli viewed Luther as a polemicist, and not above the typical reform of humanism which was unable to shed many Roman Catholic ideas…Luther was not fully committed to the Reformation and was too conservative. (p. 78)

Zwingli is also more the Reformed father of the Anabaptists than either Calvin or Luther, and took his own superior subjective view of Sola Scriptura farther than they were willing. He also likely deserves the distinction as father of the iconoclasts, those who delight in the destroying Christian art and shrines objectionable to them but revered and venerated by the Church for centuries.

Regarding Zwinglians’ boldness and impatience at reform Fr. Josiah writes:

To raise a public debate, Zwingli and his allies then sent a request to the bishop of Constance for abolition of celibacy and permission for “scriptural” preaching – meaning their preaching. Zwingli himself had been living in a secret union with a widow, Anna Reinhardt, since the beginning of 1522. On April 2, 1524, when his lover was pregnant with their first child, he married her and together they had four children….

Fr. Josiah in a footnote wrote: “The real theological father of much contemporary Protestant Evangelicalism was living in fornication while he was articulating evangelicalism.” (p. 82)

A final telling note about Zwingli was his presiding over the dissolution of 350 monasteries and the appropriation of their lands by civil authorities (similar to what Henry VIII did in England). Many of their cronies would trace their wealth for generations to these new land holdings. Again Fr. Josiah’s footnote: “Here we see one of the innumerable cases of Protestant theft on a grand scale. The Protestant assumption appears to be that believing wrongly invalidates property rights.” (p. 83) Incidentally, Luther thought Zwingli’s teaching on baptism worse than the Anabaptists’ and believed that his death in battle was God’s judgment on him.

John Calvin was born in 1509 (26/25 years after Luther and Zwingli) into an aristocratic family. His father planned an ecclesiastical career for his son. Calvin was tonsured at age 12 by the Bishop of Noyon. However, in 1533, at the age of 24 Calvin detached from his Roman position and income. Fr. Josiah wrote in his footnotes:

Calvin’s fallout with the papacy was generational. His father Gerard was a successful lawyer and accountant of sorts for the church. He was accused of corruption in regard to the estates of two priests, and was excommunicated in 1528 [Calvin 19]. He died in that state in 1531 [Calvin 22]. Calvin’s brother, Charles, was a Catholic priest, excommunicated for insulting a colleague and striking a parishioner, and, though offered absolution and last rites on his deathbed in 1537, he refused both and died excommunicate [Calvin 28]. (p. 120) [Calvin’s age in brackets provided courtesy of the reviewer.]

Calvin, a very bright student, gave up ambitions to study for the priesthood by age 20, and studied law diligently, self-publishing his first book, a translation and commentary on Seneca’s De Clementia, at his own expense. Calvin became a Protestant at age 24. Three years later Calvin would publish his first edition of his infamous Institutes of the Christian Religion. His intellect and abilities led Guillaume Farel to recruit him that same year to Geneva in July of 1536. Though asked to leave after a dispute with the city council two years later (Easter 1538) Calvin was asked to return three years later (Sept 1541) at age 32, where he, “would spend the next twenty-three years producing a massive literary corpus and endeavoring to establish the church of Geneva upon his principles. (p. 124)

Geneva’s city council accepted Calvin’s Ecclesiastical Ordinances in 1941 which “established a consistory of pastors and elders to oversee church discipline and public morality.

Fr. Josiah writes:

This body of elders was to have the power of excommunication, which was the cornerstone of his [Calvin’s] system of church polity. Through the police force, the power of this consistory extended into every aspect of personal life in Geneva, and the basis for much resistance by its citizens and grounds for the charge that Calvin created a theocracy in Geneva.

The Yankee Puritans of New England a century later would prove to be meek libertarians by comparison.

It [consistory] examined one’s religious knowledge, criticism of ministers, absences from sermons, use of charms and family quarrels. It exercised discipline against a widow who prayed requiem prayers at the grave of her departed husband, a goldsmith for making a chalice, a barber who tonsured a priest (haircut); …against one who criticized Geneva for executing a heretic; and against someone who sang a song critical of Calvin. The consistory forbade cards and ball games, regulated how much cutlery and how many plates were allowed to be used at the table, prescribed the clothing that could be worn, abolished Christmas day and made it a normal workday, and forbade brides from adorning their hair on their wedding day. Calvin’s hand was intimately involved in almost all matters of the consistory, and it took its cue from him. (pp. 125, 126)

Note here that Calvin was a ripe 32 years old, 8 years a Protestant, when this occurred. The consistory supplied Calvin with a very large salary funded by the City government to symbolize their support.

Fr. Josiah is not as critical of Calvin even offering this summary: “Calvin is especially good in his interpretation of the covenants, and his articulation of the relationship between the Old and New Testaments…maintained a brilliant Christocentric hermeneutic…set forth a very positive view of the divine law…[and] Calvin’s doctrine of the last things is where he may be most traditional [with the Holy Fathers of the Church].” Sadly, as is often the case, Calvin’s zealous youth often got the best of him.

Meanwhile Calvin and other Reformers and Protestants of his day quoted the early Church Fathers implying the Reformation’s agreement with the early Church. Yet this was and is very selective – they were quoted when they agreed with him. Calvin was disdainful of them when they departed from him:

Certainly, Origen, Tertullian, Basil, Chrysostom and other like them would never have spoken as they do, if they had followed what judgment God had given them. But from desire to please the wise of the world, or at least from fear of annoying them, they mixed the earthly with the heavenly. That was a hateful thing, totally to cast man down, and repugnant to the common judgment of the flesh.

Fr. Josiah comments:

Here is Calvin in all his arrogance and theological overconfidence. His accusations against the likes of Ss. Chrysostom and Basil the Great are that they were too worldly, too submissive to worldly powers, and not willing enough to defy merely human judgments.

These charges are ironic in that they apply far more to Calvin himself and the Protestant Reformers than to the Holy Fathers he attacks. Chrysostom and Basil were ascetic monks who were other-worldly, and show Calvin as still quite fixed to the earth by comparison. Who was the one who rejected his tonsure and married: And that a widow? Who was the one so irascible that he could not bear to be contradicted? ?[as a young man]? Who was the one who determined eucharistic practice by the judgment of the civil powers? Who was the one who received a large salary from the state? Who was the one complicit in the execution of heretics? Who was the one who died in the comfort of his own home with the approbation of the wise of Geneva, instead of in harsh exile with the opposition of the emperor? (pp. 131,132)

Like Luther, Calvin was in constant theological disputes. Fr. Josiah writes,

Calvin fought with the Anabaptists, the Zwinglians, the Lutherans, and with the Roman Catholics, while claiming that the Scripture were clear. And, though he read the Holy Fathers extensively Calvin judged them all by their level of agreement with him, imputing moral depravity where none objectively existed in order to justify their universal disagreement with him. This is self-serving and contradictory theology. (p. 133)

I will cut short here Fr. Josiah’s critiques of other Reformers like the Anabaptists and their triumph in America, The Church of England, the Catholic Counter-Reformation, and America’s folk religion (many familiar names here). These are rich and as demonstrated above, Fr. Josiah handles them with skill and insight – all from an Orthodox perspective steeped in the history and Tradition of the Church.

Historic Christian Doctrine

Nor does space allow a review of the many doctrinal issues Fr. Josiah elucidates with skill and candor. Among them are an outstanding review of the Filioque heresy and its importance, though embraced by both Protestants and Roman Catholics; an extended historical review of Orthodox Cyril Lucaris’ wrongly supposed conversion to Calvinism, and the Orthodox answer to Calvinism in the Confession of Dositheos and the Synod of Jerusalem (1672). Much here we must skip that is excellent reading.

The Fathers and Holy Tradition

However, Fr. Josiah’s cogent critique of Sola Scriptura – the notion that Scripture is a stand alone as the only infallible rule of faith and practice – merits some attention.

First and foremost is the fact that the Lord Jesus Christ and His Holy Apostles did not teach such a thing but explicitly rejected it in teaching and practice…Our problem with the Protestants is that at this point they are not biblical enough. The New Testament itself affirms that the foundational authority for the Christian and the Church is the Apostles teaching. (p. 64)

The teaching of the Apostles is itself called ‘tradition’ in the New Testament…’Now we command you, brethren, in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, that you keep aloof from every brother who leads an unruly life and not according to the tradition which you received from us.’ (2 Thess. 3:6) Tradition is the Christian way of life, or life in the Holy Spirit. Tradition is the Bible rightly interpreted. St. Paul praised the Corinthians for adhering to the Church’s tradition, ‘Now I praise you because you remember me in everything, and hold firmly to the traditions, just as I delivered them to you. (1 Corth. 11:2, 15:3 and Jude 3)

Of course today Protestants have their own Traditions…Luther’s (Lutheranism), Calvin’s (Calvinism), Zwingli’s (Baptist), with a host of variations all firmly certain they rest on the clear teaching of Scripture. The question is not If you embrace a theological ‘Tradition’…but whose is it? where did it come from? – and is it the same Tradition spoken of so often and reverently of in the pages of Holy Scripture? Fr. Josiah notes:

…the history of Protestantism, from its very root, bears witness to the lack of Apostolic authenticity of the sola scriptura doctrine. Why do Lutheran, Calvinistic, Zwinglians, and Anabaptist creeds all differ on fundamental points if the Bible alone is the only authority of the reformers? Why could not Luther and Zwingli and other Reformers agree on the nature of the very central act of Christian worship, the Holy Eucharist, if they were both simply reading the Bible and following its teachings? By cutting the cords of Holy Tradition, and placing in its stead the doctrine of sola scriptura, the Protestants ensured theological divisiveness and fracture between themselves and their descendants and have only multiplied divisions, theories, and interpretations ad infinitum, with no end in view to this day. We may judge a tree by its fruit. The sola scriptura tree has borne the fruit of division and every conceivable heresy. (p. 275)

On Salvation

Fr. Josiah writes:

The great problem with Protestant teaching on salvation is its thorough-going reductionism. In the Holy Scripture and in the writings of the Holy Fathers salvation is a grand accomplishment with innumerable facets, a great and expansive deliverance of humanity from all its enemies: sin, condemnation, the wrath of God, the devil and his demons, the world, and ultimately death. In Protestant teaching and practice, salvation is essentially a deliverance from the wrath of God. (p. 288)

This expansive and multifaceted understanding of salvation in Christ is often referred to as the fullness of salvation or salvation maximalism where limiting salvation to mere fire insurance short-changes what the Scriptures and the Church as understood about salvation.

Rather than seeing salvation primarily as a one-time past event in time, Orthodoxy sees salvation a process that occurs in the past, present, and future. Fr. Josiah comments:

As emphasized as this past event is, Orthodox Christians are very much aware that salvation is a process as much as it is a definitive act. We are saved by faith when we are baptized, for sure. However, the New Testament uses the word sozo also in the present and future tenses. In fact, the most common use of the word sozo in the New Testament is the future, not the past. Hence, to be “biblical” we must consider salvation to be primarily, not exclusively, a future reality. (p. 290)

Take, for instance the Reformed Protestant doctrine of atonement as expressed in the Westminster Confession of Faith: “Christ, by his obedience and death, did fully discharge the debt of all those that are thus justified, and did make a proper, real, and full satisfaction to his Father’s justice in their behalf.” Here we see the usual Protestant reductionism applied to the Cross of our Savior. The traditional Christian teaching expressed in the New Testament and the writings of the Fathers on the subject of the atonement of our Savior is the Cross saved us in three essential ways: on the Cross Jesus conquered death; on the Cross Jesus triumphed over the principalities and power of this evil age; on the Cross Jesus made atonement for human sins by His blood. Because the Protestants were working out of a soteriological framework of a courtroom and declarative justification, they read the teaching about the Cross through these lenses and as a result articulated a reductionistic theology of the atonement, which ignored the traditional emphasis on the conquering of death and the triumph of the demons. Everything for Protestantism becomes satisfaction of God’s justice, and by making one image the whole, even that image became distorted in Protestant articulation. (p. 294)

Note: To be fair, two Reformed theologians of the late 19th century, John Williamson Nevin and Philip Shaff noted this problem to some degree in their Mercersberg theology (see Robert Arakaki’s in-depth critique). More recently Anglican Bishop NT Wright’s writings and some of his Reformed followers in the Federal Vision movement have move away from this narrow, exclusively legal-forensic view. Sadly, as they have incorporated select aspects of Orthodox theology, they have been charged as heretics by their Reformed brethren for this select quasi-Orthodox perspective!

In regards to being “biblical” Fr. Josiah also notes:

The 2nd chapter of the Epistle of St. James explicitly affirms that we are not saved by faith alone. Luther’s importation of the word “alone” into his German translation of Roman 3:28 where the word does not exist in the Greek original is yet another Protestant abuse of the New Testament translation… “Orthodox Christians acknowledge the immense importance of the act of faith…[but] categorically deny, however, that one is saved by faith alone. (p. 289)

Finally, Fr. Josiah points to the neglect of theosis and deification:

…the greatest reductionism is found in the immense neglect of emphasis upon the heart of the New Testament teaching on salvation as union with Jesus Christ…. The theology of the Church bears witness to the fact that the mystery of salvation is accomplished not just on the Cross, but from the very moment of Incarnation when the Only-Begotten and Co-Eternal Son united Himself forever with humanity in the womb of the Virgin Mary, his Most Pure Mother. Salvation as union and communion between God and Man drips from every page of the new Testament and in the writings of Holy fathers.

This coming transfiguration of believers, this glorious resurrection and divinization of human nature in the unspeakable bliss of union with God, this shining as the stars in the Kingdom of His Father as our Savior puts it in his parabolic teachings, is the future of believers. It is hardly just forgiveness.

The Tragic reductionism of Protestant concepts of salvation has produced a very serious neglect of theosis, and has led to the serious error of objectifying fallen human life and it limitations and projecting it into the future. It has kept Protestants from understanding the potential of human transformation in this life. (pp. 296, 297)

This wonderful section is full of Apostolic teaching all too often neglected by Protestants.

Summary

This review has run a bit long due to the many long quotations. Sadly, many other good and perhaps more worthy passages should have included that have been left out. I conclude here with an exhortation.

If you are Orthodox living and working in the North America, Western Europe, Australia or New Zealand – read this book. It will help you understand what your friends, neighbors, and co-workers believe and the church they attend on Sunday.

If you are a Protestant convert or a Protestant who sincerely wishes to understand Orthodoxy – read this book. Russians and those in traditional Orthodox lands would profit in understanding western Protestants now trying to proselytize them with false doctrines.

Protestant converts living in Asia and Africa should read Fr. Josiah’s book for the same reasons! The Christianity the missionaries brought to your country is not the Ancient Faith proclaimed by the Apostles and their disciples, is rather a new theological system invented by Europeans in the 1500s reflecting the values and mentality of Western Europeans.

Thank you Fr. Josiah for this wonderful book! May its influence be multiplied and magnified within and without the Church of our blessed Savior.

Further Readings

“A Calvinist Who Crossed Over to Orthodoxy” by Robert Arakaki 29 September 2011

“Interview with Fr. Josiah Trenham”: The Examiner

Fr. Josiah Trenham — St. Andrew Orthodox Church, Riverside CA

Recent Comments