Icon – Mary in Hagia Sophia

In recent years growing numbers of Evangelicals have become interested in Orthodoxy. Many want to convert to Orthodoxy but have difficulty with certain Orthodox teachings. Without question, one of the most difficult obstacles for any Protestant Evangelical interested in Orthodoxy is Mary.

A large part of the problem lies in a communications gap between Evangelicals and Orthodox. Unlike Eastern Orthodoxy which has ancient roots going back to the Early Church, Evangelicalism is very Western, very modern, and very American in its thinking. Part of the communications problem is due to the fact that Protestants and Orthodox operate from different theological paradigms. Paradigms are frameworks that scientists use to organize their data and formulate their theory. These differences have resulted in Protestants and Orthodox using similar words with quite different meanings.

This is further complicated by a cultural gap. Many Orthodox Christians born and raised Orthodox are not fully aware of the mindset that many Evangelicals bring with them. Evangelicalism is a subculture with its own values and its own vocabulary. Evangelicalism’s distinctive vocabulary includes: “being born again,” “being Spirit-filled,” “making a decision for Christ,” “assurance of salvation,” “eternal security,” having a “daily quiet time,” “prayer partners,” “witnessing for Christ,” “feeding on the word of God” etc. Thus, there is a need for bicultural Evangelical-Orthodox who can bridge the two worlds, that is, who can explain Orthodoxy using the familiar accents of the Evangelical lingo. As an Evangelical convert to Orthodoxy my goal in this paper is to explain the Orthodox understanding of Mary in terms familiar to Evangelicals.

Mary in the Bible

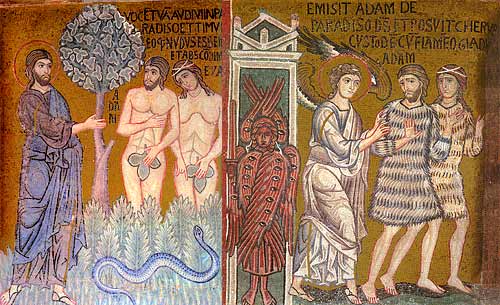

Because the Bible is the bottom line for what Evangelicals believe, we start here. One of the first things to note is that although biblical references to Mary are sparse, they are there and they are located in strategic places in the Bible. The first reference we find of Mary is in Genesis 3:15, after Adam and Eve ate the forbidden fruit. Speaking to the serpent, God said:

And I will put enmity

between you and the woman, and

between your offspring and hers;

he will crush your head, and

you will strike his heel. (NIV translation, unless noted otherwise)

In this short passage God provides a bare outline of the great plan of salvation that would be filled out later on in greater detail and colorful brush strokes in the rest of the Bible. What is so striking about Genesis 3:15 is the twofold enmity: (1) between Satan and the woman, and (2) between Satan’s offspring and the woman’s offspring. Many Evangelicals will acknowledge that the woman being referred to is not Eve, but Mary who gave birth to Jesus. The question that the Evangelical must ask is this: Why did God see fit to include a reference to the woman? Why couldn’t God just have made reference to the one who would crush Satan’s head? Why in this proto-evangelium did God pair the Savior with his mother?

This pairing of the woman and her child is a theme that occurs repeatedly in the Bible all the way up to the last book in the Bible, Revelation. The next biblical reference to this pairing is in Isaiah 7:14. In this passage Isaiah prophesied:

Therefore the Lord himself will give you a sign: The virgin will be with child and will give birth to a son, and will call him Immanuel.

According to Matthew’s Gospel, this prophecy was fulfilled in the birth of Jesus Christ.

But after he had considered this, an angel of the Lord appeared to him in a dream and said, “Joseph son of David, do not be afraid to take Mary home as your wife, because what is conceived in her is from the Holy Spirit. She will give birth to a son, and you are to give him the name Jesus, because he will save his people from their sins.

All this took place to fulfill what the Lord had said through the prophet: “The virgin will be with child and will give birth to a son, and they will call him Immanuel” — which means, “God with us.” (Matthew 1:20-23)

In his letter to the Galatians Paul writes that Christ’s being born of the Virgin Mary was not a chance occurrence but something that took place in the fullness of time, i.e., at the most strategic moment in human history.

But when the time had fully come, God sent his Son, born of a woman, born under law, to redeem those under law, that we might receive the full rights of sons (Galatians 4:4-5).

What is interesting about these verses is that they imply that the Incarnation was instrumental in our salvation. This challenges the Protestant paradigm which views our salvation almost exclusively in terms of Christ’s dying on the cross.

The next time this strategic pairing is found is in the book of Revelation (Note 1). The book of Revelation is quite popular among many Evangelicals for it teaches them about God’s plan of salvation for the entire world and how world history will culminate in the Second Coming of Christ. In Revelation 12 we come across a grand tableau depicting the cosmic war between Christ and Satan.

A great and wondrous sign appeared in heaven: a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet and a crown of twelve stars on her head. She was pregnant and cried out in pain as she was about to give birth. …. The dragon stood in front of the woman who was about to give birth, so that he might devour her child the moment it was born. She gave birth to a son, a male child, who will rule all the nations with an iron scepter. (Revelation 12:1-2, 4-5)

An Evangelical reading Revelation 12 is bound to become uncomfortable with the effusive language used to describe Mary. Mary is described in vivid symbolic language that refers to her being clothed with the divine glory (her being clothed with the sun), her preeminence in the order of creation (her standing over the moon), and her preeminence among God’s elect (the twelve stars representing either the twelve tribes of Israel in the Old Testament or the twelve apostles of the Church in the New Testament). This is a far cry from the humble virgin that gave birth to Christ in the manger and then quietly retires to the side lines in Protestant theology.

In summary, when we take into consideration the entire scope of the biblical witness from Genesis to Revelation we find a clear pattern bearing witness to the strategic role of the Virgin Mary in salvation history. According to the Bible Mary does not occupy a peripheral or marginal role but a strategic role in salvation history. The critical turning point of our salvation was when God entered history as a man.

During the month of August the Orthodox Church remembers the life and example of Mary. One of the assigned gospel readings is taken from Luke 11:27-28. In response to the woman who cried out, “Blessed is the mother who gave you birth and nursed you,” Jesus responded, “Blessed rather are those who hear the word of God and obey it.” At first I was surprised to hear this verse because many Evangelicals use this verse to put down Mary. But as I gave it further thought, I began to understand what it is that made Mary a model of faith. The woman thought that what made Mary great was her physical motherhood but what made Mary truly great was her willingness to do God’s will (Luke 1:38). In submitting to God’s will Mary did what the first Eve failed to do. In saying “Yes” to God, Mary became the Second Eve who reversed the Fall and opened the way for the Savior to enter into history. Mary’s giving birth to Christ is a unique experience, but her obedience to the word of God is something all Evangelicals can share in (Matthew 12:46-49, Mark 3:31-35, Luke 8:19-21).

Mary the Mother of All Evangelicals

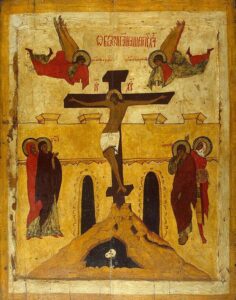

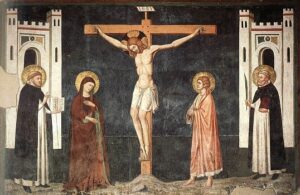

Crucifixion – Eastern style

One of Jesus’ last words as he hung on the cross were his words to Mary and to the apostle John. To Mary Jesus said, “Woman, here is your son,” and to John he said, “Here is your mother.” (John 19:26-27) This passage can be interpreted on two levels: literal/historical or allegorical/typological. Both approaches are valid. On the typological level it can be said that John represents the Christian and that in accepting Jesus’ death on the cross the Christian receives Mary as their mother. Mary was not only Jesus’ mother, she is our mother as well.

In Revelation 12:17 we read that all who obey God’s commandments and who hold to the testimony of Jesus are Mary’s children. What is striking about this verse is that it describes the two distinctive traits of Evangelicals: their zeal to be biblical and their zeal to be witnesses for Christ. If so, then in light of Revelation 12:17 Mary is the Mother of all Evangelicals. Protestant Evangelicals need to get over their hang-ups and in obedience to the Bible, accept Mary as their Mother.

The Bible teaches the concept of spiritual motherhood. This principle can be found with respect to Sarah, Abraham’s wife. Peter writes, “You are her daughters if you do what is right and do not give way to fear” (I Peter 3:6). Paul uses the Sarah/Hagar example in Galatians 4 and uses this contrast to make the point that the Church is our mother (Galatians 4:26).

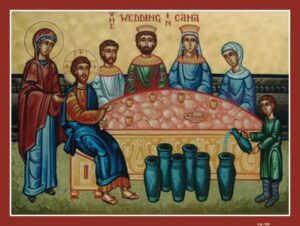

“Do whatever He tells you.”

Thus, to be Mary’s children means to be like her, following her example. Just as Mary was committed to doing God’s will, so we should be committed to doing God’s will. When she heard the astounding announcement from the angel Gabriel she responded, “I am the Lord’s servant. May it be done to me as you have said.” (Luke 1:38) Mary, likewise was devoted to bearing witness to Jesus. At the wedding at Cana she instructed the servants, “Do whatever he tells you.” (John 2:5) Doing whatever Jesus tells us to do means total acceptance of Christ’s lordship over our lives. Accepting Mary as our Mother does not weaken our commitment to Christ, rather it strengthens our commitment to Christ. Drawing closer to Mary leads us closer to our God and Savior Jesus Christ.

Mary in the Liturgy

For the Evangelical visiting the Sunday Liturgy is the best way to learn what the Orthodox Church really believe about Mary. (It is strongly recommended that the visiting Evangelical attend a parish where the Liturgy is in English. Going to an ethnic parish where the Liturgy is even in a mixture of English/Greek or English/Russian can be distracting and confusing.) For the Orthodox the Divine Liturgy is theology in action. The beginning part of the Liturgy consists of several litanies — set prayers — that close with a reference to Mary and then with reference to the Holy Trinity. When the priest reaches the end of a litany he will then say:

Remembering our most holy, pure, blessed and glorious Lady, the Theotokos and ever-virgin Mary, with all the saints, let us commend ourselves and one another, and our whole life to Christ our God.

At the end of our prayers we are reminded of Mary’s total commitment to Christ and that we are also remembering the example set by the other Christians who have gone before us. The call to commit our lives to Christ should warm the heart of any Evangelical. Years ago I made a personal commitment to Christ and now years later I’m renewing that commitment every Sunday in the Liturgy. Several times during the Liturgy I recommit my life to Christ and at the same time I commit the lives of my friends and family to God’s loving care.

As the Liturgy progresses we encounter Mary again in the Nicene Creed. The Nicene Creed is recited every Sunday and at every liturgical celebration. The Nicene Creed starts off with what the Church believes about God the Father, then what it believes about Christ’s divine nature and his human nature.

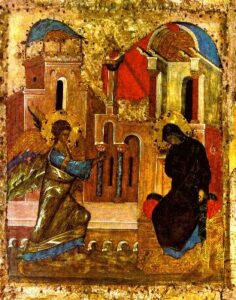

Icon – Annunciation

For us and for our salvation he came down from heaven

and became incarnate by the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary

and became man.

The first thing to note is that the Nicene Creed situates “our salvation” in relation to the Incarnation, not in relation to the Crucifixion as Evangelicals are wont to do. The next thing to note is that the Incarnation involved the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary. Mary played an integral part in the Incarnation; without her cooperation the Incarnation would not have happened.

Then, following the consecration of the bread and the wine the congregation sings:

It is truly fitting to call you blessed, O Theotokos; you are ever-blessed, utterly pure, and the Mother of our God. More honorable than the Cherubim, and far surpassing the glory of the Seraphim, remaining inviolate you gave birth to God the Logos. Truly the Theotokos, we magnify you.

Here an Evangelical might cringe at the effusive language praising Mary, wondering: Is all this exalted language biblical? A careful reading of the Bible show that it is.

Blessed — “Blessed are you among women, and blessed is the child you will bear!” (Luke 1:42)

Theotokos (God-bearer) — “Blessed are you among women, and blessed is the child you will bear!” (Luke 1:42; see also Isaiah 7:14, Matthew 1:21-25, Luke 2:6-7, Revelation 12:5)

Ever-blessed — “From now on all generations will call me blessed….” (Luke 1:48)

All-holy — “But just as he who called you is holy, so be holy in all you do; for it is written: ‘Be holy, because I am holy.'” (I Peter 1:15-16)

Utterly pure — “Blessed are the pure in heart for they will see God.” (Matthew 5:8). “Everyone who has this hope in him purifies himself, just as he is pure.” (I John 3:3)

Mother of God — “The virgin will be with child and will give birth to a son, and will call him Immanuel– which means, ‘God with us.'” (Matthew 1:23, cf. Isaiah 7:14)

More honorable than — “You made him a little lower than the heavenly beings the Cherubim and crowned him with glory and honor.” (Psalm 8:5) “And God raised us up with Christ and seated us with him in the heavenly realms in Christ.” (Ephesians 2:6)

Many Protestants are afraid that venerating Mary will eventually lead to worshiping her. Protestants’ confusion when Orthodoxy claims that it venerates Mary but does not worship her arises from differences in their understanding of worship. Where the sermon is central to Protestant worship, the center of Orthodox worship is the Eucharist. Kimberly Hahn, an Evangelical who converted to Roman Catholicism, makes this observation:

I could not figure out why it was that it seemed to be that Catholics worshiped Mary, even though I knew worship of Mary was clearly condemned by the Church. Then I got an insight: Protestants defined worship as songs, prayers and a sermon. So when Catholics sang songs to Mary, petitioned Mary in prayer and preached about her, Protestants concluded she was being worshiped. But Catholics defined worship as the sacrifice of the body and Blood of Jesus, and Catholics would never have offered a sacrifice of May nor to Mary on the altar (1993:145).

Thus, it is impossible for Orthodox Christians to worship Mary. This misunderstanding of the Orthodox veneration of Mary can be traced back to Protestantism’s departure from the historic Christian pattern of worship.

After repeated visits to Orthodox worship services, I saw that the focus of Orthodox worship is on the Holy Trinity and Mary plays a secondary role in Orthodox theology. Evangelicals are afraid of being misled by tradition run amok unchecked by Scripture. The important thing is to understand that Orthodox faith and practice is based on the teachings of the Apostles. The Sunday worship service uses the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom which dates back to the fifth century and which has changed little in the centuries following. Because the Liturgy does not change, it protects our theology. The Liturgy functions like the two rails that keep the train on track and heading in the right direction. It should be reassuring for Evangelicals to know that the Liturgy guards us from excesses like putting Mary on the same level as Jesus or separating her from Jesus and that the Liturgy leads us to Christ. This is different from when I was a Protestant and was worried that some strange new doctrine might come down from the denominational headquarters.

The Ecumenical Councils

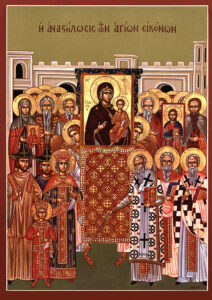

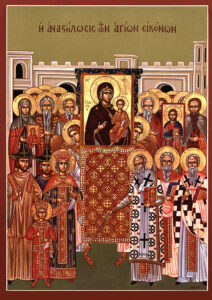

Icon – Seventh Ecumenical Council

Many of the titles for Mary used in the Liturgy come from the early theological debates. The debates were not so much about Mary but about Christ’s two natures, the Incarnation, and the Trinity. It was at these Ecumenical (Universal) Councils that the Early Church defined the essential elements of the Christian Faith. The Councils’ decisions to assign various titles to Mary: The Virgin Mary – Nicea I, A.D. 325, Theotokos – Ephesus, A.D. 431; Ever-Virgin – Constantinople A.D. 553, were all intended to safeguard the divinity of Christ.One would think that the Councils’ language would be effusive in their description of Mary. However, the language of the Councils was quite austere with respect to Mary. In order to understand what the Ecumenical Councils taught about Mary, it is important to understand how the titles ascribed to Mary served to protect a right understanding of who Christ is. Timothy Ware writing about the title “Theotokos” notes:

The appellation Theotokos is of particular importance, for it provides the key to the Orthodox cult of the Virgin. We honour Mary because she is the Mother of our God. We do not venerate her in isolation, but because of her relation to Christ. Thus the reverence shown to Mary, so far from eclipsing the worship of God, has exactly the opposite effect: the more we esteem Mary, the more vivid is our awareness of the majesty of her Son, for it is precisely on account of the Son, that we venerate the Mother (The Orthodox Church, p. 262).

Here we see the deep links between the Liturgy and the Ecumenical Councils. For Orthodoxy, church history is living history. Church history is not something found in the history books but something we relive every Sunday in the Liturgy.

Mary and the Icons

An Evangelical visitor will be struck by the visible prominence of Mary in the architecture of the Orthodox church. Looking towards the front of the church, one sees the icon of the Virgin Mary on the left of the royal door leading to the altar and the icon of Christ on the right side. Above the altar one may see the expansive icon of the Virgin Mary holding the Christ child. The icons are not just pretty pictures. They depict powerful truths about Christ and our salvation.

An Evangelical visitor will be struck by the visible prominence of Mary in the architecture of the Orthodox church. Looking towards the front of the church, one sees the icon of the Virgin Mary on the left of the royal door leading to the altar and the icon of Christ on the right side. Above the altar one may see the expansive icon of the Virgin Mary holding the Christ child. The icons are not just pretty pictures. They depict powerful truths about Christ and our salvation.

The huge, eye catching icon of Mary that catches the attention of so many Evangelicals needs to be viewed in its proper context. In Orthodox architecture if one looks up at the ceiling one will see the icon of Christ the Pantocrator — signifying Christ’s being in heaven as the All Ruling One. Then as one’s gaze moves further down one sees the icon of the Virgin with Child — signifying Christ’s coming down from heaven for our salvation. After that, if one looks directly at the altar one sees the cross — signifying Christ’s descending even further to the point of dying for our salvation. This is Paul’s famous hymn in Philippians 2:5-11 in visual form.

The icons by the royal door also teaches us about salvation history. The icon of the Virgin Mary holding the Christ child on the left represents the First Coming of Christ and the icon of Christ on the right represents the Second Coming of Christ. In the first coming Christ comes in humility to save us and in the second coming Christ comes in glory to judge humanity. It is significant that it is the practice of the Orthodox church for confession to be done before the icon of Christ on the right. On a symbolic level the icon of the Virgin Mary depicts the age of the Church in which the Church presents Christ to the world as a witness to God’s saving mercy. The altar area beyond the icon symbolizes the age to come.

Mary’s Virginity — The Biblical Evidence

One objection that Evangelicals have is the Orthodox belief of Mary being ever-virgin, i.e., her perpetual virginity. Every icon of Mary shows three stars or diamonds on her forehead and her two shoulders. These three stars or diamonds represent Mary being a virgin before, during, and after the birth of Christ. This is not some vague popular lore but defined as a fundamental dogma of the universal Church at the Fifth Ecumenical Council at Constantinople in A.D. 533.

The bottom line for Evangelicals is: What does the Bible teach? When one considers the biblical data for or against Mary’s perpetual virginity, the surprise is how ambiguous the biblical record is. It is quite easy for Evangelicals to marshal the requisite biblical proof texts to defend the Virgin Birth of Christ (Isaiah 7:14, Matthew 1:18-25, Luke 1:26-38). However, when Evangelicals claim that Mary had other children besides Jesus they are beginning to skate on thin ice. In making this assertion they point to Mark 6:2-3:

When the Sabbath came, he began to teach in the synagogue, and many who heard him were amazed. “Where did this man get these things?” they asked. “What’s this wisdom that has been given him, that he even does miracles! Isn’t this the carpenter? Isn’t this Mary’s son and the brother of James, Joseph, Judas, and Simon? Aren’t his sisters here with us?” And they took offense at him. (Mark 6:2-3)

What this passage teaches us is that Jesus is Mary’s son, but it does not teach that Mary had other sons and daughters beside Jesus. What Mary’s relationship is with these four men is not clear in the text. To say that Mary was their mother is one possible reading of the passage but not the only necessary reading of the passage. Another reading of the passage is that they were Joseph’s sons from a prior marriage before Joseph was betrothed to Mary. The historic Christian understanding has been that they were Joseph’s sons from a previous marriage. The Protestant understanding is a recent one.

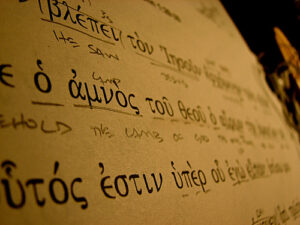

Another interesting piece of biblical data is the fact that while the Bible does support the fact that Mary was betrothed to Joseph, it does not explicitly state that Mary and Joseph ever married. In first century Palestine the betrothal was a solemn ceremony in which the man and the woman were promised to each other. This was part of a two step process of a betrothal followed by a wedding. The fact that Matthew and Luke never mentioned that Joseph and Mary became married lends indirect support for the interpretation that they were betrothed but never took the second step of consummating their relationship through sexual union. It is telling that Matthew and Luke used the word μναομαι “to betroth” rather than the word γαμεω “to marry” to describe Mary’s relationship with Joseph (see Matthew 1:18 and Luke 2:5). In light of the biblical evidence Evangelicals must be open to the possibility that Mary was Joseph’s betrothed but not fully his wife.

Evangelicals point to Matthew 1:25 where it reads: “But he had no union with her until (‘εως) she gave birth to a son.” The way this verse reads to many Evangelicals is that Joseph refrained from having sexual intercourse with Mary until she gave birth to Jesus and then he had sexual intercourse with her. But there are other ways of reading this text. The Greek conjunction ‘εως does not necessarily denote a sharp temporal division of before and after. The semantic range for ‘εως allows for a continuity both before and after. For example, in the Great Commission passage (Matthew 28:19-20) Christ promised that he would be with us always even until the end of the age. No Evangelical would interpret this to mean that after the Second Coming Christ would no longer be with us.

What is even more problematic for the Evangelicals is the fact none of the Protestant Reformers, Martin Luther or John Calvin, interpreted the passage this way. Calvin criticizes those who deny Mary’s perpetual virginity and he points out that this interpretation does not fit the sense of the passage,

John Calvin

“Helvidius takes issue with this passage, and caused great disturbance at one time in the Church. He deduced from it that Mary was only a virgin up to her first birth, and thereafter bore other children by her husband. The perpetual virginity of Mary was keenly and copiously defended by Hieronymous. …. Joseph is said to have had no intercourse with her, until she brought forth, but this too only applies to that same period. What followed after, he does not tell.” (Calvin’s New Testament Commentaries Vol. 1 page 70; italics added).

In terms of the historic consensus we find Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholics, and the original Reformers in agreement on Mary’s perpetual virginity! Evangelicals who deny Mary’s ever-virginity find themselves outside of the historic mainstream on the fringe.

Mary’s Perpetual Virginity — The Theological Angle

It is quite ironic that Evangelicals who played such a stalwart role in defending the Virgin Birth against the theological liberals in the early twentieth century would have such a hard time accepting Mary’s ever-virginity. They insist quite strongly that after giving birth to Christ, Mary had normal sexual relations with Joseph and that she had several more children after that. What is puzzling is why Protestants insist on making Mary’s having sex with Joseph into something akin to theological dogma. If anyone would have difficulty accepting Mary’s perpetual virginity it would be the theological Liberals who deny the Virgin Birth. But for Evangelicals interested in Orthodoxy, probably the biggest issue is their puzzlement as to why Orthodoxy treat it so seriously? To put it bluntly, “Why does Orthodoxy make such a big deal about Mary being ever-virgin? What’s the big deal about the whole thing?”

What does Mary’s ever-virginity have to do with our salvation? If we use the Protestant paradigm of salvation which focuses on the forgiveness of sins, it’s peripheral. But if we use the Orthodox paradigm of salvation which focuses not just on justification but on the totality of our salvation in Christ, it’s central. Mary’s ever-virginity is linked not to our justification but to our sanctification and glorification in Christ. Our salvation is linked to Mary’s salvation. This is because Jesus came to save not just individuals but the human race. Just as Mary was saved by Christ, so each one of us will be saved.

Mary is the prototype of our salvation. Take the analogy of the model home. In Hawaii we have numerous planned communities. Oftentimes when we drive around the island we see huge open tracts of land with nothing on it, just a sign announcing the developer’s plan to build homes on the land, and maybe a model home showing what the future homes will look like. The Developer is God, the future planned community full of homes and happy families is redeemed humanity in the age to come. Mary is the model home. Mary is living proof of Christ’s power to save us. Salvation is not just something far off in the future, in the life of the Theotokos we have concrete evidence of our ultimate salvation.

Sanctification forms an integral part of our salvation in Christ. One of the great miracles is that not only are our sins forgiven but that Christ takes profaned, defiled beings like us and makes us holy for service in his holy temple. I have found in Orthodoxy a tangible sense of holiness in worship. Experiencing the holiness of God in the Divine Liturgy has helped me grasp the significance of Mary’s carrying Christ in her womb for nine months. Being pregnant with Christ was a sanctifying experience for Mary in a very profound way.

Mary’s perpetual virginity shows that the Incarnation had real and lasting consequences. When Mary accepted Christ into her life she was transformed internally and physically. As the Theotokos (the God Bearer) Mary is the fulfillment of the Old Testament archetypes: the Ark of the Covenant, the Holy of Holies, the burning bush, the jar containing the manna, the sacred lamp in the Temple, the altar of incense, Aaron’s rod which mysteriously budded, the sealed East Gate in Ezekiel’s temple. In the Old Testament once something has been set aside and dedicated to sacred use, it is sacrilegious to reuse it for ordinary purposes. In Mary’s being pregnant with Christ we see something far surpassing any of the archetypes in the Old Testament. For her to be pregnant with another child after that would be like a priest pouring soda into the communion chalice! or the Israelites using the Holy of Holies as a storage room! For the Orthodox Christian the Protestant notion of Mary having other children or her having intercourse with Joseph shows a shocking lack of appreciation of holiness. An Evangelical may just shrug their shoulders with indifference, a sign of their inexperience with God’s holiness.

Mary’s perpetual virginity is also linked to our ultimate salvation in Christ. Her ever-virginity is a prophetic foreshadowing of the life to come. In his debate with the Sadducees Jesus noted:

When the dead rise, they will neither marry nor be given in marriage; they will be like the angels in heaven” (Mark 12:25).

Where marriage and sex is distinctive to the present age, virginity and celibacy points to the age to come. Mary being both Virgin and Mother spans the two ages: the present age and the future age. Mary is like the first Eve in Genesis who gave birth to children, and yet she is the Second Eve who foreshadows life in the hereafter. Thus, Mary spans the two ages. This is a good example of what the noted Evangelical theologian George Ladd referred to in his The Presence of the Future as: “present fulfillment and future eschatological consummation” (1974:133). Mary is the Second Eve who changed the course of human history with her “Yes” to God and her giving birth to the Savior of the world. But if one adopts the Protestant view that Mary had children like other mothers, then Mary is an ordinary woman who belongs squarely in the present fallen age; there is no decisive intervention that foreshadows the coming age. The Incarnation was not a nine month blip that disappeared into history but more like a “eucatatrosphe” — an event that took place in a brief moment in time with long-lasting and widespread consequences for the good of the human race.

Mary Our Prayer Partner

Another obstacle for Evangelicals is the Orthodox practice of praying to Mary. We ask Mary to pray with us, that is, we ask her to be our prayer partner. We do not ask Mary to give us what we need (only God can do that), but we ask her to join us in prayer. Orthodox Christians who are sharing their faith with Protestants need to be aware of the Protestants’ fear of any attempt to put anything between them and Christ. We need to emphasize to our Protestant friends that for Orthodox Christians there is only one Mediator between God and men, Jesus Christ (I Timothy 2:5).

The Orthodox Church’s understanding of Mary is grounded in Scripture. The Orthodox understanding of prayer is based upon the ancient doctrine of the “communion of saints.” Orthodox Christians are very conscious of the fact that we do not pray alone but that we are constantly surrounded by the great cloud of witnesses (Hebrews 12:1) and that we are participating in the ongoing heavenly worship (Revelation 5 and 7).

What helped me to accept Mary’s role as intercessor was a heartwarming anecdote I had heard from Tom Telford when I was missions chair of my former church.

Once I visited these three elderly saints who were all in senior citizen homes nearby. I went to see Gladys first. I knocked on the door and she could barely see. I said, “Gladys, do you know who this is?” She said, “Tommy!” and gave me a big hug. As we talked, I asked her what she did all day. She said, “Come here and I’ll show you.” She had an old yellow legal pad with fifty-two names of missionaries written down. “I spend my day praying for these people. See, Tommy, here’s your name.” (Tom Telford 1998:50-51)

What Gladys has been doing so faithfully day in and day out is exactly what Mary has been faithfully doing day in and day out in heaven. I would guess that after Gladys passes on and goes to be with the Lord, she’s not going to stop praying for Tom Telford. The Orthodox Church believes that Mary and the saints in heaven are fervently praying for those of us here on earth.

Protestantism’s Emotional Scars

The Protestant avoidance of Mary has its roots in the psychological trauma of the Protestant Reformation. The religious controversy between Roman Catholicism and the Protestant Reformation ripped apart the social, political and religious unity of Western Europe which left emotional scars on Western Christianity. Many times when someone undergoes a traumatic experience, they repress the memory of that experience. It is as if they completely forget that incident had ever occurred. However, psychologists know that that experience shapes the victims’ attitudes, perception and actions long after the incident happened. They may no longer remember the incident but its impact is still evident in their life. It controls them even if they are not aware of its influence. They usually need therapy to confront the incident and reconstruct their thinking so that it no longer controls their lives.

When Protestantism rejected Mother Church in the form of Roman Catholic Church it necessarily had to reject Mary. It rejected Mary by minimizing her role in God’s plan of salvation. It accepted her as one believer among many others but it refused to honor her for her part in salvation history. The loss devastated the soul of Protestantism. Protestantism is a lonely religion. We come to faith in Christ alone — on our own, as individuals. We gather on Sunday mornings as like-minded individuals. We read the Bible alone — we cannot rely on others to tell us what the Bible means. There is a certain emptiness in the Protestant systematic theologies despite their logical coherence. Not knowing Mary as Mother is a great loss and what is even more sad is that we do not know of our loss.

In all fairness it should be noted that the Protestant tendency to neglect Mary was not part of the original Reformation. It seemed to be a later development, most likely a subsequent development of the Puritan movement in the 1600s. While Reformers like Calvin strongly affirmed the Church as Mother, for some reason this understanding has been largely neglected by many Protestants. This is my personal guess as to why Mary is not given due honor in Protestantism. I’m sure there are other explanations as well.

Protestants have certain legitimate criticisms of Roman Catholicism. However, what Evangelicals should keep in mind is that despite the surface similarities there are significant differences between Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism. Frederica Matthewes-Green in her popular book At the Corner of East and Now describes well the different temperaments in the East and the West:

In Orthodoxy, Mary is a strong figure, not a helpless or vapid one. She’s our Captain because she is first in the pack, the leader of all Christians, and it is her example we all follow, men as well as women. …. Western Christianity, I find, has a comparatively feminine flavor. The emphasis is on nurturing and comfort; reunion with God occurs as he heals our inner wounds. In the West, we want God to console us and reassure us; in the East, we want God to help us grow up and stop acting like jerks. (pages 89-90)

The differences between Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy lie at a deeper level. Father Alexander Schmemann in For the Life of the World writes,

It is significant that whereas in the West Mary is primarily the Virgin, a being almost totally different from us in her absolute and celestial purity and freedom from all carnal pollution, in the East she is always referred to and glorified as Theotokos, the Mother of God, and virtually all icons depict her with the Child in her arms.

There is a tendency in Roman Catholicism to emphasize Mary’s exceptionalism to the neglect of her commonality with the human race. Pope John Paul II in his encyclical letter Dives in Misericordia (On the Mercy of God, page 30) notes: “Mary is also the one who obtained mercy in a particular and exceptional way, as no other person has.” This stress on Mary’s exceptionalism can put at risk our grasp of the Incarnation. Our salvation depends upon Christ being fully human, and Christ’s humanity depends upon Mary’s humanity. Orthodoxy with its stress on Mary as the Theotokos has maintained a healthier balance than in the West. Evangelicals journeying to Orthodoxy need to keep in mind that Eastern Orthodoxy is quite different from Roman Catholicism, and not let their anti-Catholic prejudice get in the way of hearing what the Orthodox Church has to say about Mary.

Moving Towards Orthodoxy

For the Protestant Evangelical, becoming Orthodox involves more than changing one’s theology. Unlike the Protestant understanding of faith as mental comprehension of doctrine, for Orthodoxy faith is lived out in worship. For a Protestant like me, the challenge of becoming Orthodox was not just in accepting what Orthodox Christians believed about Mary but also loving her as the Orthodox do. A good illustration of the difference between Protestantism and Orthodoxy can be found in a story of a theology professor from Holland making a trip to an Orthodox church.

One day he was in an Orthodox Church in Moscow standing in front of an icon of Mary and Christ when an old Russian woman approached him. She could see at a glance that Hannes was a foreigner. Few Russians could afford such clothing. And she could see he wasn’t Orthodox — he hadn’t crossed himself, he hadn’t kissed the icon. He was looking at it as one might look at a painting in a museum. “Where do you come from?” she asked. “Holland,” Hannes replied. “Oh, yes, Holland. And are there believers [as Russians refer to Christians] in Holland?” “Yes, most people in Holland belong to a church.” He could see the doubt in her face.

She began to cross-examine him. “And you also are a believer?” “Yes, in fact I teach theology at the university.” “And people in Holland, they go to church on Sunday?” “Yes, most people go to church. We have churches in every town and village.” “And they believe in the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit?” She crossed herself as she said the words. “Oh, yes,” Hannes assured her, but the doubt in her face increased — why had he not crossed himself? Then she looked at the icon and asked, “And do you love the Mother of God?” Now Hannes was at a loss and stood for a moment in silence. Good Calvinist that he was, he could hardly say yes. Then he said, “I have great respect for her.” “Such a pity,” she replied in pained voice, “but I will pray for you.” Immediately she crossed, kissed the icon, and stood before it in prayer.

“Do you know,” Hannes told me, “from that day I have loved the Mother of God.” (Jim Forest Praying With Icons p. 109)

This story summarizes the fundamental difference between Evangelicals and Orthodoxy. The Evangelical approach to Mary is one of distant respect, whereas the Orthodox approach is one of love and trust. For Protestants Mary is a distant historical figure but for Orthodox Christians she is with us in our worship on Sunday morning.

In my journey to Orthodoxy what I found most helpful was the principle of not forcing myself to do Orthodox things but to grow in my Orthodoxy. As I grew in my understanding of the Liturgy my approach to worship and prayer underwent a gradual change. I began making the sign of the cross and bowing towards the icon of Christ during worship. I took another step closer to Orthodox worship when I began bowing my head to the icon of the Theotokos. I bowed my head out of respect for her courageous commitment to Christ and her playing a key role in our human history. The next change came in my private devotions. Where before my quiet time consisted of bible readings and free form prayer, I began using the Orthodox Morning Prayers. I found my daily quiet time becoming more Trinitarian in focus. I also found myself no longer excluding Mary from my prayers but linking my personal prayers with the great heroes of faith like Mary and John the Baptist.

Sola Scriptura vs. Holy Tradition

An essential part of becoming Orthodox is renouncing the Protestant principle of sola scriptura (bible alone) and accepting Holy Tradition as it is handed down by the Church. This is why Mary is such a major problem for Protestants interested in Orthodoxy. Not everything in Orthodoxy can be found in the Bible. Evangelicals need to be assured that Holy Tradition will not contradict Scripture. This is because Scripture is an integral part of Holy Tradition and because the source of this Tradition is Christ.

The difference here is between the Protestant principle of sola scriptura (bible alone) and the Orthodox principle of Holy Tradition. Protestants claim to derive their theology from the Bible. They trust in the Bible as the Word of God but they are reluctant to trust the Church’s teaching authority. Protestants in rejecting the teaching authority of the Church are basically self-taught in their theology. Orthodoxy on the other hand believes there are no self-taught Christians, ultimately what we believe is handed down to us by means of Holy Tradition through a long line of transmission that goes back to the Apostles.

When I was a Protestant Evangelical I used the inductive bible study method. Then I supplemented the inductive bible study method with the early Church Fathers. I found myself moving closer to Orthodoxy but I was still operating as a Protestant in that I was still acting as a self-teaching Christian. I was like a student who enjoyed studying on his own, but who did not go to the classrooms.

However it was the collapse of my Protestant theology that forced me to take Orthodoxy seriously. This theological crisis was caused by two discoveries: (1) that much of what makes up modern Evangelicalism goes back only to the nineteenth century and (2) that the two cardinal dogmas of the Reformation — sola fide and sola scriptura — were never part of the Early Church. At the same time my studies in church history led me to the conclusion that Orthodoxy was right in its claim that it kept the teachings of the Early Church without change. At that point my thinking shifted from skepticism to that of deep respect to that of trust. I became convinced that the Orthodox Church could be trusted on the essentials of the Christian Faith. At that point I was ready to become Orthodox.

Much of what I’m writing here about Mary came after I became Orthodox, not before. When I joined the Orthodox Church I did not have all the answers to my questions about Mary, e.g., Mary’s perpetual virginity. My basic attitude was that if the Orthodox Church got things right on the important issues of Christ and the Trinity, she could be trusted to get things right on the Virgin Mary. When I joined the Orthodox Church it was like seeking admission to the university, enrolling for classes, and putting myself under the teaching authority of the professors (bishops). I stopped being a self-taught Protestant and began enjoying the benefit learning from great theologians of the past: Irenaeus of Lyons, Athanasius the Great, the Cappadocian Fathers et al.

Together We are Saved, Alone We are Lost

Do I need to believe in the Virgin Mary to be saved? If we mean by salvation Christ dying on the cross for our sins and our going to heaven — as Protestants understand salvation — the answer is: No. But if we mean by salvation Christ coming down from heaven to take on human nature, our being baptized into Christ’s death and resurrection, and our incorporation into the Church, the body of Christ — as Orthodoxy understands salvation — then the answer is: Yes.

The differences here are rooted in differences in theological paradigms. The Protestant understanding of salvation focuses on Jesus’ death on the cross and our sins being forgiven. For the Orthodox, Christ came to save us in the fullest sense of the word. The Orthodox theological paradigm focuses on Christ’s Incarnation: his life, death, resurrection, and ascension to heaven. Where Protestants take a minimalist approach to salvation, Orthodoxy emphasizes the fullness of our salvation in Christ. Accepting Mary is important for our salvation because eternal life consists of life in community. Christianity is a relational religion. When we enter into a personal relationship with Christ, we enter into a relationship with God the Father and we receive the Holy Spirit. Jesus came to bring us back home to God and to heaven where all the saints and angels dwell.

But you have come to Mount Zion, to the heavenly Jerusalem, the city of the living God. You have come to thousands upon thousands of angels in joyful assembly, to the church of the firstborn, whose names are written in heaven. (Hebrews 12:22-23)

Just as Jesus Christ is the Way to the Father, so Mary is the doorway to the Church. Honoring Mary opens the way to venerating the saints. Asking Mary to pray for us opens the way for us to ask the prayers of the saints. Accepting Mary into our lives is an integral part of accepting the “communion of saints” mentioned in the Apostles Creed.

In closing, I would like to note that in becoming Orthodox I did not stop being an Evangelical. Orthodoxy for me does not mean the abandonment of Evangelical principles but the fulfillment of Evangelicalism. Mary is the greatest Evangelist of all time, she opened the door for Christ the Savior to come to us (Isaiah 7:14, Revelation 12:5). Mary shows us the way of Christian discipleship. Mary’s words at the wedding at Cana, “Do whatever he tells you” (John 2:5) means that listening to her means accepting Jesus as Lord and Savior of our lives. Mary leads us to faith in Christ which is the very heart of Evangelicalism.

Robert Arakaki

Note 1 — The woman in this passage can be understood to refer to the nation of Israel or to Mary. Revelation is full of symbolic language which makes it quite difficult to interpret. Many Orthodox Christians prefer to interpret this passage allegorically (the woman = Israel), the reason being that according to Holy Tradition Mary gave birth to Christ without suffering birth pains. The Orthodox Study Bible is ambivalent about this passage.

Bibliography

Calvin, John. A Harmony of the Gospels: Matthew, Mark and Luke. Vol. I. Calvin’s Commentaries Series. A.W. Morrison, translator. David W. Torrance and Thomas F. Torrance, editors. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1972.

Forest, Jim. Praying With Icons. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 1997.

Hahn, Scott and Kimberly. Rome Sweet Home: Our Journey to Catholicism. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1993.

John Paul II. Dives in Misericordia (On the Mercy of God). Boston, Massachusetts: Daughters of St. Paul, 1980.

Ladd, George Eldon. The Presence of the Future: The Eschatology of Biblical Realism. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1974.

Matthewes-Green, Frederica. At the Corner of East and Now: A Modern Life in Eastern Orthodoxy. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam, 1999.

Schmemann, Alexander. For the Life of the World: Sacraments and Orthodoxy. Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1988.

Telford, Tom with Louis Shaw. Missions in the 21st Century. Wheaton, Illinois: Harold Shaw Publishers, 1998.

Ware, Timothy. The Orthodox Church. Revised edition, 1997. New York: Penguin Books, 1963.

Recent Comments