Two Approaches to the Trinity

The Reformed tradition’s monergistic premise is consequential, not just for soteriology, but for its understanding of the Trinity. This is because theology (the nature of God) and economy (how God relates to creation) are integrally related. To separate the two would result in a defective theological system. A comparison between the Eastern and Western theological traditions demonstrates how different approaches to the Trinity led to different understandings of salvation.

In the early Christological debates Christians struggled to reconcile the theological concepts of monotheism and monarchy (LaCugna 1991:389; Kelly 1960:109-110). The Cappadocian Fathers — Basil the Great, Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory of Nazianzen — solved the problem by abandoning the principle of monarchy in favor of a trinitarian monotheism. They argued that the unity of the Godhead stems not from the Being (Ousia) of God but from the Person (Hypostasis) of the Father (Kelly 1960:264). Gregory of Nazianzen wrote:

The Three have one nature, viz. God, the ground of unity being the Father, out of Whom and towards Whom the subsequent Persons are reckoned (in Kelly 1960:265).

Zizioulas noted the emphasis on the hypostasis over the ousia has major implications for our understanding of the Trinity.

In a more analytical way this means that God, as Father and not as substance, perpetually confirms through “being” His free will to exist. And it is precisely His trinitarian existence that constitutes this confirmation: the Father out of love–that is, freely–begets the Son and brings forth the Spirit. If God exists, He exists because the Father exists, that is, He who out of love freely begets the Son and brings forth the Spirit (Zizioulas 1985:41; emphasis in original).

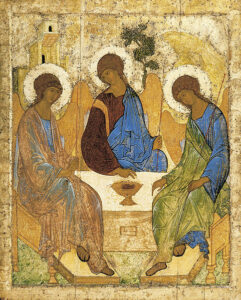

The Cappadocians grounding the doctrine of the Trinity in the Persons, not the Being, provides a solid basis for the statement in I John 4:16: “God is love.” Love is not an attribute of God but what God is: the Trinity of Persons forever united in love. Thus, God is not an isolated Individual, a monad but a communion of Persons.

God exists as the mystery of persons in communion; God exists hypostatically in freedom and ecstasis. Only in communion can God be what God is, and only as communion can God be at all (in LaCugna 1991:260).

Augustine took a different approach from the Fathers in emphasizing the divine Essence (Ousia) in constructing his doctrine of the Trinity (LaCugna 1991:91; Kelly 1960:272). This theological move arose from his locating relationality within the divine Being. Zizioulas observed that this emphasis on the Godhead as a Trinity of coequal Persons tends to push the Essence (Ousia) to the forefront.

The subsequent developments of trinitarian theology, especially in the West with Augustine and the scholastics, have led us to see the term ousia, not hypostasis, as the expression of the ultimate character and the causal principle (αρχη) in God’s being (Zizioulas 1985:88; emphasis in original).

Vladimir Lossky in The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church noted:

The Latins think of personality as a mode of nature; the Greeks think of nature as the content of the person (1976:58).

This monumental theological move by Augustine shaped the theological trajectory of Western Christianity for generations – extending even to the present day.

The result has been that in textbooks on dogmatics, the Trinity gets placed after the chapter on the One God (the unique ousia) with all the difficulties which we still meet when trying to accommodate the Trinity to our doctrine of God. By contrast, the Cappadocians’ position–characteristic of all the Greek Fathers–lay, as Karl Rahner observes, in that the final assertion of ontology in God has to be attached not to the unique ousia of God but to the Father, that is to a hypostasis or person (Zizioulas 1985:88; emphasis in original).

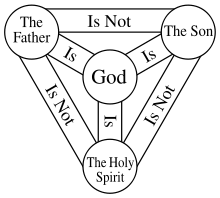

Western Christianity’s foregrounding of the ousia (being) of God has led to logical difficulties. It has resulted in theologians having to make statements that resemble Zen koans used by Buddhist monks. A common explanation often goes like this: the Father is God, the Son is God, the Holy Spirit is God; but the Son is not the Father, and the Son is not the Holy Spirit; but there is not three gods but only one God. Formulation like this often frustrate and bewilder many. It is radically different from the Eastern understanding of the Trinity as the communion of three Persons who share in the same Essence.

Western Christianity’s foregrounding of the ousia (being) of God has led to logical difficulties. It has resulted in theologians having to make statements that resemble Zen koans used by Buddhist monks. A common explanation often goes like this: the Father is God, the Son is God, the Holy Spirit is God; but the Son is not the Father, and the Son is not the Holy Spirit; but there is not three gods but only one God. Formulation like this often frustrate and bewilder many. It is radically different from the Eastern understanding of the Trinity as the communion of three Persons who share in the same Essence.

The most prominent manifestation of the Western Augustinian approach is the Filioque clause. As originally phrased the Nicene Creed implied that the Holy Spirit originated from the Person of the Father but the insertion of the Filioque implied the Holy Spirit originated from the Essence shared by the Father and the Son (Filioque). Lossky writes about the Filioque:

The Greeks saw in the formula of the procession of the Holy Spirit from the Father and the Son a tendency to stress the unity of nature at the expense of the real distinction between the persons. The relationships of origins which do not bring the Son and the Spirit back directly to the unique source, to the Father–the one as begotten, the other as proceeding–become a system of relationships within the one essence: something logically posterior to the essence (Lossky 1976:57).

Thus, the Filioque marks a theological watershed between Western Christianity (Roman Catholic and Protestant) and Eastern Orthodoxy. It can also be considered as the beginning of the West’s innovative approach to doing theology.

A Theological Continental Divide

A Theological Continental Divide

There is a place in the Continental Divide where a stream veers off in two directions. One branch ends up in the Pacific Ocean and the other the Atlantic Ocean. Similarly, with Augustine and the Cappadocian Fathers a theological equivalent of the Continental Divide emerged that would result in two quite different theological systems.

Augustine’s focus on God’s being as the starting point for theologizing has been consequential for the way salvation has been understood in the West (Lacugna 1991:97). One disturbing implication of Augustine’s approach to the Trinity is the sense of God as impersonal inscrutable One.

If divine substance rather than the person of the Father is made the highest ontological principle–the substratum of divinity and the ultimate source of all that exists–then God and everything else is, finally, impersonal (LaCugna 1991:101; emphasis in original).

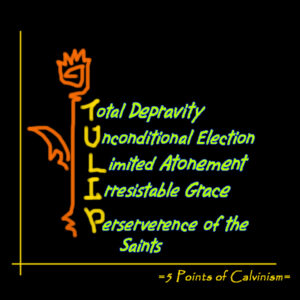

A theological system based on an impersonal and omnipotent deity leads to a monergistic soteriology and the subsequent denial of free will and love. The doctrines of Unconditional Election and Irresistible Grace assume an all powerful God who in his inscrutable wisdom unconditionally elects a few then inexorably effects their salvation. It is almost as if the Augustinian West might say of our election or reprobation: “It’s not personal, it’s just abstract ontology.”

The Protestant Reformers in their quest to uphold the dogma of sola fide with its implicit monergism had to choose between the God’s abstract/impersonal sovereignty and God’s personal and relational love. Calvin, with unflinching clarity, upheld the sovereignty of God and the principle of monergism with all its terrifying implications in his explication of double predestination. By leaving no room for free will, Calvin’s theology led to a relapse to monarchical monotheism undermining the basis for trinitarian monotheism.

The Western Augustinian approach to the Trinity provides the basis for a forensic soteriology which views salvation in terms of legal righteousness and the transference of merit. The forensic approach contains two significant assumptions: (1) the relationship between God and mankind is understood in terms of an impersonal command-obedience and (2) rather than Man in the “image and likeness of God,” it assumes an ontological divide between humanity and God. The penal substitutionary atonement theory being based on the transfer of merit maintains the ontological gap between God and humanity. Notably, it does not require communion between God and the elect.

Where Western theology tends to maintain the ontological gap between God and humanity, Orthodoxy emphasizes the gap being bridged in the Incarnation. The gap being bridged here by Christ’s incarnation is ethical-relational, humanity being sullied by sin and in need of healing and reconciliation. There is also an ontological gap which is bridged by Christ who unites divinity and humanity in one Person. The Incarnation makes possible a personal encounter with God because the Son assumed human nature from the Virgin Mary. According to the Chalcedonian Formula, the human and divine natures are joined in the Person of Jesus Christ. The technical term for this is hypostatic union. The significance of the hypostatic union is that a person to person encounter such as that implied by faith in Christ is crucial to our salvation. The priority of the hypostasis means that a physical viewing of the Christ “according to the flesh” is not enough (cf. II Corinthians 5:16), a true encounter with Christ entails trust in Christ. The story of the woman with the issue of blood in Mark 5:24-34 shows that the woman’s personal encounter with Christ was more important than physical contact with the hem of his clothes. The interconnection between being and person is crucial for our salvation in Christ which culminates in our deification — humanity “partaking of the divine nature” by grace what Christ is by nature (see II Peter 1:4).

The Cappadocians’ stress on the hypostasis (person) leads to Orthodoxy understanding salvation as relational: with God and with others. Through faith in Christ we come to know the Father and receive the Holy Spirit; we are made members of the Church, the body of Christ. What we do collectively as the Church takes precedence over what I do individually in private. Through the sacraments of baptism and chrismation the convert is reborn into the life of the Trinity. This is because the sacraments are covenantal actions based upon an interaction or exchange between persons. The Orthodox emphasis on the hypostasis means that every sacrament is a personal encounter with God.

Person and being are dynamically linked, what affects the one, affects the other. This interrelationship helps us to understand the Orthodox teaching of theosis — our ongoing transformation into the likeness of Christ and deification (sharing in the divine nature). Theosis assumes that through our union with Christ, the Incarnate Word of God, and our receiving the Holy Spirit we become “partakers of the divine nature” as taught by the Apostle Peter in II Peter 1:4. In theosis we remain human but we are transformed by divine grace. We are transformed much like the way the metal sword in the fiery furnace becomes hot and bright like the fire while still remaining metal. Where Western theology has a tendency to be mechanistic and deterministic in its soteriology, Eastern Orthodoxy has a more relational and dynamic approach.

Calvinism and the Western Tradition

There is no indication that the Reformers broke from the Western Augustinian tradition and followed instead the Eastern approach to the Trinity. Steven Wedgeworth in his essay: “Is There a Calvinist Doctrine of the Trinity?“ sought to rebut theologians who advanced the idea that Calvin broke from the Nicene trinitarian tradition and offered a modified trinitarian doctrine. Pastor Wedgeworth argued that far from offering a new theological paradigm, Calvin remained faithful to the traditional Nicene trinitarian theology. However, Wedgeworth failed to note that what Calvin advocated was the Western Augustinian understanding of the Trinity. Furthermore, he failed to note that there existed an alternative understanding of the Trinity, the Eastern Cappadocian approach. Wedgeworth’s failure to discuss the Cappadocian approach is disappointing especially because in end note 27 is a quote from Calvin which sounds very much like the Eastern Fathers. Calvin wrote of God the Father: “He is rightly deemed the beginning and fountainhead of the whole divinity” (Institutes 1.13.25). While this sentence could be interpreted to mean that Calvin had some sympathy for the Eastern approach, it needs to be reconciled with his acceptance of the Filioque.

This leads me to pose two questions for my Reformed friends:

(1) Has the Reformed tradition critically assessed the Filioque clause in light of the Orthodox criticism?, and

(2) Has any Reformed denomination ever considered repudiating the Filioque and returning to the original language of the Nicene Creed (381)?

Coming soon — Does Reformed monergism have heretical implications?

Robert Arakaki

Recent Comments