Part 4 of 4. Parts 1, 2, and 3.

In 1995, the New Geneva Study Bible was published by Thomas Nelson Publishers under the editorial leadership of R.C. Sproul and J.I. Packer.

R.C. Sproul has ambitious goals for this new study bible including using it to evangelize Russia.

He writes:

Beyond the borders of America, the New Geneva Study Bible may be used to expand the light of the Reformation to lands where the original Reformation never reached, especially to Russia and Eastern Europe. Source

What should be the attitude of an Orthodox believer in Russia towards the New Geneva Study Bible? I would say: cautious skepticism. Having been a Protestant Evangelical I can understand the enthusiastic Calvinist’s desire to share the Good News with everyone everywhere. However, as a convert to Orthodoxy I am quite conscious of the limitations of Reformed theology. In the spirit of caveat emptor (let the buyer beware), I list below some of my concerns about the New Geneva Study Bible and the original sixteenth century Geneva Bible.

The Bible and Interpretation

As discussed in an earlier blog posting theological tradition is the foundational bedrock upon which every study bible is rooted in and upon which it rests. The New Geneva Study Bible (like ALL Protestant study bibles) is thus not pure exegesis, but grows out of the Reformed tradition. This theological tradition is quite recent going back only to the 1500s. On the other hand the Orthodox Study Bible commentary rests on the teachings of the early church fathers. This interpretive tradition goes as far back as the second century and reflects a broad catholic tradition shared by Christians all across the Roman Empire and even beyond.

As discussed in an earlier blog posting theological tradition is the foundational bedrock upon which every study bible is rooted in and upon which it rests. The New Geneva Study Bible (like ALL Protestant study bibles) is thus not pure exegesis, but grows out of the Reformed tradition. This theological tradition is quite recent going back only to the 1500s. On the other hand the Orthodox Study Bible commentary rests on the teachings of the early church fathers. This interpretive tradition goes as far back as the second century and reflects a broad catholic tradition shared by Christians all across the Roman Empire and even beyond.

There’s a certain irony in the fact that BOTH the New Geneva Study Bible and the Orthodox Study Bible have in common the NKJV translation of the New Testament! If the differences cannot be attributed to differences in translation, then what is the reason for the differences in commentary? If one takes a step back one soon becomes aware that the commentary arise from a certain interpretive community. That is, we do not read the Bible alone but our understanding of the Bible is influenced by the community we are part of.

When one looks at the Reformed tradition one finds a theological tradition confined to parts of Europe. Furthermore, the Geneva Bible represents one specific, narrow stream of Protestantism. If one wants to study the theology of the early English Reformers, the sixteenth century variants of the Geneva Bible (not the updated version) is a good choice. But if one wants understand how Christians have historically understood the Bible from the early days to the present the Orthodox Study Bible is the better choice.

Passing Fad or Enduring Classic?

The Geneva Study Bible’s popularity was relatively short lived in comparison to the King James Version. Where the KJV appealed across the spectrum of Protestant denominations, the Geneva Bible appealed primarily to English Puritans. Thus, the Geneva Bible can be considered a passing fad or a transitional translation that prepared the way for the enduring classic of English literature, the King James Bible.

The recent attempt to bring back the Geneva Bible goes against the flow of history. It appeals principally to neo-Reformed Christians and is essentially a niche Bible. Its popularity will likely be short lived.

An Accurate Translation?

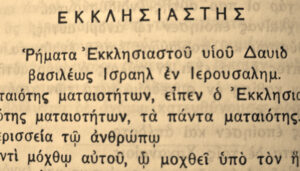

“The Greek World of the Old Testament” Source

A bible translation is only as good as its source text. The Geneva Bible like other Protestant bibles uses the Hebrew Masoretic text as the basis for its Old Testament translation. Historically, the shift to the Masoretic text is significant. Protestantism’s preference for the Hebrew text stems from Renaissance humanism’s ideal ad fontes—the belief that the path to true knowledge is through reading the classical texts in their original tongues. But this new humanist ideal marks a radical departure from the early church fathers’ desire to be discipled by the Apostles, not worldly wisdom. It was the Greek Old Testament (Septuagint) and the Greek New Testament that the Apostles and early Christians knew as their Bible.

Many of the Old Testament passages in the New Testament are either direct quotes or paraphrase from the Septuagint, not the Hebrew Masoretic text. Textual variations between the Hebrew and Greek Old Testament quotes are for the most part minor, but from time to time they will diverge; in that case which one should one prefer? I would suggest the older source text should be given preference. This makes sense in light of the fact that the Septuagint was produced about two to three centuries before the birth of Christ. The Masoretic text would not be compiled by Jewish scholars until the 600s to 900s. This makes the Greek Septuagint almost a thousand years older than the Hebrew Masoretic text!

A Conservative or Innovative Bible?

The Geneva Bible was one of the first bibles to tamper with the biblical canon by excluding the deuterocanonical books (aka Apocrypha). This is not a minor issue but centers on the question: Is this book or writing inspired by God? It takes a certain amount of audacity to claim to have the authority to make that determination!

In my first posting on the Geneva Bible I traced the gradual evolution of the Geneva Bible. The first printing in 1576 contained the biblical canon much like the Roman Catholic Church’s but by 1599 the Apocrypha was left out. This action stemmed from the increased hostility between Protestants and Roman Catholics. It can also be seen as stemming from the English Reformers’ intolerance of the in-between status of the deuterocanonical books which were considered inspired but not on the same level as other parts of the biblical canon. Gary Michuta in an insightful article showed how the exclusion of the Aprocrypha led to changes in the marginal notes that sought to show the New Testament reliance on the Apocrypha, e.g., Matthew 27:48 and Wisdom 2:18, and Hebrews 1:3 and Wisdom 7:36.

This tampering with the biblical canon demonstrates the Reformed tradition’s innovative character. This is a radical departure from the historic Bible, not a conservative return to the early Church as some would like to think.

The Need for a Protestant Study Bible

The attempt to bring back the Geneva Bible represents a step backwards for Protestants today. The Geneva Bible reflects English Protestantism in the late 1500s before the emergence of King James Version in 1611. Since then many more English translations have appeared each with their own strengths and weaknesses. It is hard to accept the claim made by some that the Geneva Bible is to be preferred over all other English translations.

What is needed instead is a Protestant Study Bible that reflects the rich diversity of Protestant readings of the Bible. Such a bible would help advance our understanding of Protestantism’s complex and even contradictory relations with Scripture. The Reformed tradition is one facet of Protestantism’s complex and often conflicted hermeneutical history. The Protestant Study Bible that I am suggesting here would be a useful resource for Protestant-Orthodox interfaith dialogue. We share the same Scripture but we are separated by differing readings of Scripture. These divergent readings arise from fundamentally different hermeneutical starting points. Where Orthodoxy assumes Apostolic Tradition as the normative interpretive framework for reading Scripture, the Protestantism insisted on sola scriptura which in time took on an increasingly nuanced and qualified forms resulting in often contradictory interpretations.

A Political Agenda?

The New Geneva Study Bible seems to have become intertwined with a certain political agenda. We find in the treatise “The Forgotten Translation” posted on genevabible.com linking the Geneva Bible to American democracy.

Thanks to the Institutes of the Christian Religion, his printed sermons, the Academy, his commentaries on nearly every book of the Bible (except the Song of Solomon and the Book of Revelation), and his pattern of Church and Civil government, Calvin shaped the thought and motivated the ideals of Protestantism in France, the Netherlands, Poland, Hungry, Scotland, and the English Puritans; many of whom settled in America. The great American historian George Bancroft stated, “He that will not honor the memory, and respect the influence of Calvin, knows but little of the origin of American liberty.” The famous German historian, Leopold von Ranke, wrote, “John Calvin was the virtual founder of America.” John Adams, the second president of the United States, wrote: “Let not Geneva be forgotten or despised. Religious liberty owes it most respect.”

As wonderful as some moderns might believe the American democracy may be, it must not be affixed to the Word of God. The Bible belongs to the Church catholic and not just to one particular polity. One has to wonder if the Neo-Reformed missionary project is intertwined with an attempt to civilize the world according to the “American Way.” Rather than respect Russia’s Orthodox Christian heritage, the New Geneva Bible (Reformation Study Bible) seems to be an attempt to replace it with American Protestantism.

Conclusion

To summarize, despite the admirable motives for attempting to bring back the Geneva Bible there are significant problems with this particular bible:

(1) Its commentary notes come out of a relatively recent theological tradition, the Protestant Reformation which originated in the 1500s;

(2) It was popular for a brief period of time until superseded by the King James Version;

(3) It used the Hebrew Masoretic text instead of the Septuagint;

(4) It changed the Old Testament canon by leaving out certain books that the Christian Church had long considered Scripture;

(5) Its recent come back seems to be connected to the neo-Reformed movement within Evangelicalism; and

(6) The recent endeavor to export it Russia rests on the assumption that Reformed theology is superior to Orthodox Christianity.

So what should an Orthodox Christian in Russia say if offered a copy of the Geneva Bible? I would suggest that even if offered a free copy of the Geneva Bible, one should reply: Thanks, but no thanks. They might even challenge Protestant zealots to consider how the Geneva Bible is in reality a radical departure from historic Christianity. That it might be just as much a political tract promoting modern democratic Americanism as it is a “new and improved” Protestant version of the Bible. They could also offer to sit down with their Protestant friend and compare the Geneva Bible with the Orthodox Study Bible.

Robert Arakaki

Recent Comments