In a recent blog posting Pastor John Armstrong wrote about his paradigm shift on the Incarnation. I found his article very helpful for illustrating the different ways Protestants and Orthodox approach the Incarnation. Armstrong wrote:

For now I have been thinking about how the Orthodox Church has a doctrine of salvation that includes the whole world, or the teaching of cosmology. Simply put the Orthodox do not treat the incarnation, the cross, and resurrection as separate events when explaining our salvation. I have concluded that this approach has to be correct because it fills in some holes in our Western way of thinking that is too individualistic. It also challenges the tendency in the West to center on legal categories when it seeks to explain the cross and God’s love. (Emphasis added.)

The Incarnation is one area where Reformed and Orthodox Christians frequently talk past each other not being fully aware of the differences separating them. When I became Orthodox I criticized some of my friends for not taking the Incarnation seriously, and some felt insulted by this. As bible believing Evangelicals they strongly believed in the Incarnation, so how could I accuse them of not taking the Incarnation seriously? I felt frustrated because I did know quite how to explain the reasons for my criticism. Over time I became aware that the differences were paradigmatic, that is, the role/function of the Incarnation in the Protestant theological system is quite different from its place in Orthodoxy.

Evangelicals do believe in the historicity of the Incarnation, but theologically they view it as a preliminary step, secondary to the big event of Christ’s atoning death on the Cross. For many Protestants all salvation is assumed in Christ’s death. Humanity’s chief problem was solved; the sinless Son of God took on our guilt on the Cross and if we believe in Christ our sins will be forgiven — our legal standing before God will be restored (righteousness) thereby entitling us to certain benefits in the kingdom of God, e.g., eternal life, resurrected bodies, a place in heaven, the right to ask God for things (intercessory prayer) etc.

But for Orthodoxy the Incarnation is just as significant for our salvation as Christ’s dying on the Cross, as well as his third day resurrection. We are saved by the person of Jesus Christ, not just by that one thing he did on the Cross. In baptism we are united to Christ’s death and his resurrection, we receive the Holy Spirit and are incorporated into his Body (the Church). We cease to be autonomous beings and now live in the context of the liturgical and sacramental life of the Church. In the course of the liturgical cycle of the major feast days of the Orthodox Church we participate in the mysteries of Christ’s Incarnation, his Nativity, his presentation in the Temple, his Baptism in the River Jordan, his Transfiguration, his ascent to Jerusalem, his entry into Jerusalem, his death on the Cross, his Resurrection, and his Ascension. In the Incarnation the Eternal entered into history. The life of Christ recounted in the Gospels is not a sequence of events but transcends the limitations of chronological time. Through the Church’s liturgical life we participate in the baptism at the River Jordan or Christ’s Transfiguration on Mount Tabor as if we were there. The Orthodox Holy Week services are more than Sunday School lessons. In these services we participate in Christ’s last week on earth. This is ontologically possible because of the Incarnation. We are no longer separated by two thousand years of time, because we are in the Body of Christ, the Church.

Despite the differences in theological paradigms it appears the lines of communication are becoming clearer between Reformed and Orthodox Christians. We are no longer talking past each other. Below is an excerpt from a recent Facebook thread that I participated in (emphasis added). I wrote:

Charles, In Protestantism the focus is on an event – Christ’s dying on the cross for our sins. In Orthodoxy the focus is on a Person and the life He lived — the arc of Christ’s life beginning with his taking on human nature, his birth, his growing up, his ministry and teachings, his death on the Cross, his third day resurrection, his ascension into heaven, his sending the Holy Spirit, and his glorious Second Coming. Jesus is the Second Adam who recapitulated our life. When I was a Protestant I couldn’t quite figure out how all the events fit together. It seemed that the Cross was the essential thing for our salvation but all the other things weren’t as important. With Orthodoxy’s emphasis on the Incarnation — the God-Man entering into human history — all the pieces fit together into one coherent picture. –Robert

Charles replied:

Robert, I agree that Protestantism in general can focus on the cross a little too much. That is why I am glad that I am Reformed =D. I agree that the cross isn’t the only component to the gospel–it is crucial to also take into account the estates (humiliation and exaltation) and offices (prophet, priest, and king) of Christ. The period between the Incarnation and the Crucifixion would signify the estate of humiliation, and the period between Resurrection, Ascension, Intercession, and the 2nd Coming would be the estate of exaltation. So in essence, I guess we would disagree about the role of the Incarnation–to the Eastern Orthodox, it seems that it is the core. For me (and Reformed theology), it seems that the Incarnation is merely a step in the process for eschatological inauguration, fulfillment, and realization. -Charles

So while Charles and I agreed to disagree, a genuine dialogue did take place between the Reformed and Orthodox traditions. This is a small but important first step in Reformed-Orthodox dialogue.

Paradigm Shifting

My paradigm shift began when I did some reflecting on the Nicene Creed. I noticed that the particular location of the word “salvation” in the Creed. The Nicene Creed states: “For us and for our salvation he came down from heaven and was incarnate of the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary and was made man. . . .” The Creed then proceeds to recount Christ’s suffering, his death on the Cross, his third day resurrection, his ascension to heaven, and his future return in glory. I thought to myself that if a Protestant were to write the Nicene Creed they would state that Christ came down from heaven, took on human flesh, then died on the Cross for our salvation etc. As I followed the grammatical structure of the Nicene Creed I began to see that our salvation stems from a whole series of things that Jesus Christ did as the God-Man. Reciting the Nicene Creed Sunday after Sunday had a powerful influence on my thinking. It shook me out of my more narrow Protestant thinking and reoriented me to the holistic thinking of the early Church.

Pastor Armstrong’s “it fills in some holes in our Western way of thinking” describes well what happens when one encounters a better paradigm. One does not reject the earlier data as one experience a better and more comprehensive understanding of how the data relates to other data. I found in the Nicene Creed a theological paradigm at odds with an often exclusive Protestant penal substitutionary model of salvation. Salvation history is more than just the singular event of the crucifixion; salvation encompasses God’s sovereign mercy in the flow of human history culminating in the coming of the God-Man Jesus Christ who through the Incarnation entered into the flow of human history.

Doing Theology Through Worship

One thing that struck me on my journey to Orthodoxy was how much of its theology is done through worship. In the West much of theology is done through books and sermons; in Orthodoxy much of its theology is articulated in its liturgical services. Much of what I learned about the Orthodox understanding of the Incarnation came, not from a book, as from Orthodox hymnography. Liturgical worship in Orthodoxy has a theological function unparalleled to that in the Reformed tradition. There seems to be nothing similar to it in the Reformed tradition. I learned much of my Reformed theology from books, not hymns. It is as if “Reformed hymnography” is an oxymoron.

This is why inquiring Protestants will be invited to attend the Orthodox services. This is not about a “warming of the heart” experience that “confirms” a religion as some cults would claim. We invite people to the services because one simply cannot grasp the fullness of the Orthodox Faith by just reading theological books. One or two visits will not suffice; it takes several months of faithful attendance before one begins to grasp how Orthodoxy does theology. One does not become an expert on Orthodoxy after attending a few services. It takes time to absorb all that’s goes on during an Orthodox service. So, you will be asked, “Come and See.” It is in the Liturgy that one sees Orthodox theology in action.

In the liturgical hymns and prayers of the Church we learn about the significance of the Incarnation. One frequent theme is the paradox of the Incarnation, e.g., the Infinite God becoming a finite human being or the unapproachable Judge approaching sinful humanity in humble mercy. We find this paradox in the prayer below sung during the fifth week of Lent:

The angelic nature was wholly surprised at the great act of thine Incarnation; at beholding the Unapproachable (in that he is God) becoming Man approachable by all, walking among us, and hearing from all, Alleluia. (Triodion, Saturday of the Fifth Week, Nassar p. 11; underscore added)

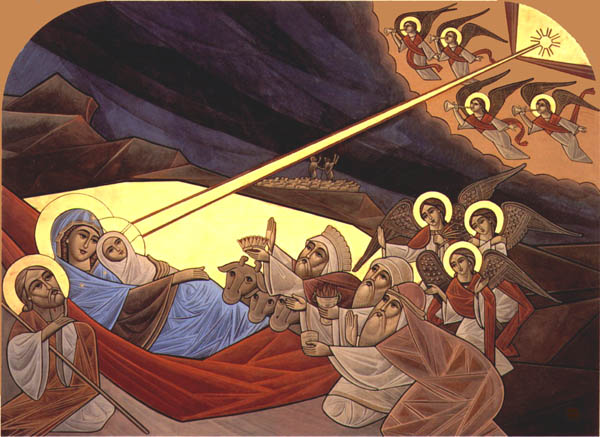

Christmas is a natural occasion for celebrating Christ’s two-fold nature. In the example below we see the paradox of the invisible God becoming visible for our salvation, and the infinite Son becoming confined to the womb of a Virgin.

Today the invisible Nature doth unite with mankind from the Virgin. Today the boundless Essence is wrapped in swaddling clothes in Bethlehem. Today God doth guide the Magi by the star to worship, indicating beforehand his three-day Burial by the offerings of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. Wherefore, we sing to him saying, O Christ God, who wast incarnate of the Virgin, save our souls. (Menaion – Sunday after Christmas, Nassar, p. 412; underscore added)

Another example of the Incarnation’s importance to Orthodoxy can be seen in the service for Christ’s circumcision. Here the Incarnation is linked to Christ as the perfect Jew who fulfilled the Law and in so doing paved the way for the New Covenant.

O most compassionate Lord, while yet God after thine essence, thou didst take human likeness without transubstantiation; and having fulfilled the law thou didst accept willingly circumcision in the flesh, that thou mightest annul the shadowy signs and remove the veil of our passions. Glory to thy goodness, glory to thy compassion, glory to thine ineffable condescension, O Word. (Menaion – The Circumcision, Nassar p. 423; underscore added).

Orthodox hymnography interweaves the Incarnation into Palm Sunday in an absolutely stunning way I never imagined when I was a Protestant. In the Palm Sunday hymn the Incarnation is subtly introduced by means of comparing the exalted heavenly throne with the lowly earthly throne. There is nothing in Protestant theology that would disallow this blending but it is striking that the theme of the Incarnation is not usually heard when Protestants celebrate Palm Sunday.

The Word of God the Father, the Son who is coeternal with him, whose throne is heaven and whose footstool is the earth, hath today humbled himself, coming to Bethany on a dumb ass. (Menaion – Palm Sunday, Nassar pp. 733-734)

Orthodoxy’s liturgical cycle can have a tremendous formative influence on one’s theological thinking. Pastors frequently lament how hardly anyone remembers their sermons. This is not so much the pastor’s fault as the inherent limitations of didactic teaching. We are not brains on a stick but embodied souls; as creatures made in God’s image we need to be engaged with our whole being in our worship. This is the advantage of liturgical worship. After hearing the hymns about the Incarnation sung repeatedly the theology gets engraved both consciously and subconsciously on our souls. All this is complemented by icons, incense, prostrations, and Scripture readings which interweave with each other to form the fabric of Orthodox worship.

Conclusion

Both Protestants and Orthodox affirm the historicity of the Incarnation. (Protestant Liberals who reject the historicity of the Incarnation have left the historic Christian Faith.) This has resulted in two quite different understandings of the Christian faith. First, with respect to God’s saving grace in Christ Protestants tend to view salvation as a point in time, an event — Christ’s death on the Cross; Orthodoxy on the other hand views salvation as an arc – Christ’s descent from heaven, his life and death, and his ascent to heaven. Second, with respect to salvation Protestants tend to define it as accepting a message about what Christ has done for us on the Cross. Among Evangelicals it has been reduced to “making a decision” to accept Christ. Orthodoxy views salvation as union with Christ. In Orthodoxy accepting Christ as Lord and Savior means undergoing baptism. Life in union with Christ means life in the Church, the body of Christ. The Incarnation means the embodiment of divine grace: in the person of Jesus of Nazareth, the Church, the sacraments, the Eucharist, etc. There is a certain subjectivity in the Protestant understanding of the sacraments as an outward sign of an inward grace. But the fact is even in the presence of an unbeliever the sacraments of the Orthodox Church are vehicles of divine grace in a very real sense. The efficacy of the sacraments is the result of the Church being the body of Christ.

Pastor Armstrong’s recent paradigm shift on the Incarnation is significant. It will likely have a ripple effect on his Reformed theology. He noted taking the Incarnation seriously opens the way to understanding salvation as union with Christ and in turn to the real presence in the Eucharist. These two themes are prominent in Mercersburg theology. While not as prominent as other theological schools, Mercersburg Theology probably represents the strongest point of contact between Reformed Protestantism and the early Church. I anticipate that Pastor Armstrong’s paradigm shift will stimulate further Reformed-Orthodox dialogue. Paradigm shifts can have unexpected cascading effects. In my case and other Reformed Christians Mercersburg theology became a bridge that took us to the early Church then eventually into the Orthodox Church. It will be interesting to see how Pastor Armstrong’s theological paradigm shift will unfold over time.

Pastor Armstrong’s recent paradigm shift on the Incarnation is significant. It will likely have a ripple effect on his Reformed theology. He noted taking the Incarnation seriously opens the way to understanding salvation as union with Christ and in turn to the real presence in the Eucharist. These two themes are prominent in Mercersburg theology. While not as prominent as other theological schools, Mercersburg Theology probably represents the strongest point of contact between Reformed Protestantism and the early Church. I anticipate that Pastor Armstrong’s paradigm shift will stimulate further Reformed-Orthodox dialogue. Paradigm shifts can have unexpected cascading effects. In my case and other Reformed Christians Mercersburg theology became a bridge that took us to the early Church then eventually into the Orthodox Church. It will be interesting to see how Pastor Armstrong’s theological paradigm shift will unfold over time.

Robert Arakaki

See also my earlier article: “Do Protestants Take the Incarnation Seriously?”

References

Mother Mary and Kallistos Ware. 2002. Festal Menaion. St. Tikhon’s Seminary Press.

Seraphim Nassar. 1993. Divine Prayers and Services of the Catholic Orthodox Church of Christ. Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese. Englewood, New Jersey.

Recent Comments