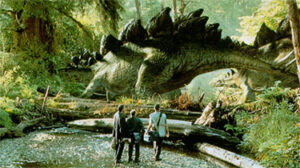

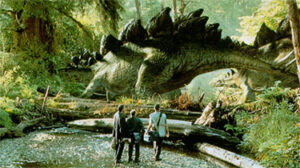

In the movie Jurassic Park is an unforgettable scene where a group of humans see living breathing dinosaurs towering over them, munching on leaves on the tree tops. The dinosaurs were the product of careful biological engineering. Scientists extracted DNA from dinosaur fossils, reconstructed the original DNA strand, inserted the reconstructed DNA into egg embryos, and then hatched the eggs.

In the movie Jurassic Park is an unforgettable scene where a group of humans see living breathing dinosaurs towering over them, munching on leaves on the tree tops. The dinosaurs were the product of careful biological engineering. Scientists extracted DNA from dinosaur fossils, reconstructed the original DNA strand, inserted the reconstructed DNA into egg embryos, and then hatched the eggs.

Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park is an apt metaphor of the recent quest among Protestant for the ancient Church. Examples of this yearning include: Robert Webber’s ancient-future faith network, Peter Leithart’s Reformational catholicism, and the convergence church movement. These recent movements have earlier precedents in the 1800s, e.g., Mercersburg Theology and the Oxford Movement. The Protestant quest for the ancient Church is similar to the paleontologists’ fascination with the lost past of dinosaurs. Having broken away from the corruptions of Roman Catholicism, Protestants asserted they were now in a position to return to the purity and simplicity of ancient Christianity.

The desire to reconnect with the past is a natural one. It is like an adopted child wanting to learn about his or her birth parents. This interest in antiquity is also biblical. The prophet Jeremiah wrote about seeking after the good way, the ancient paths (Jeremiah 6:16). The book of Proverbs talked about respecting the “ancient boundary stone” put in place by the forefathers (Proverbs 22:28).

Reconstructing the Past

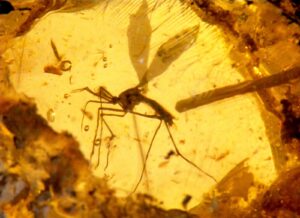

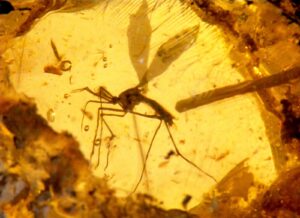

Extracting dinosaur DNA

The novel Jurassic Park can be seen as a metaphor of the flaws within Protestant ecclesiology. If one pays close attention to the story line of Jurassic Park one becomes aware that the dinosaurs are not real dinosaurs in the sense of being identical to those that existed in the Mesozoic era. The dinosaurs of Jurassic Park were laboratory creations, the product of careful scientific research. In the same way there is a certain artificiality in the Protestant quest for the early Church. Where the scientists in the laboratories of Jurassic Park worked from DNA extracted from dinosaur fossils, Nevin and Schaff worked in seminary libraries seeking to excavate ancient church texts. More recently, Webber and Leithart used the same methods attempting to renew the church by selectively drawing on the church fathers and early liturgies.

Within Jurassic Park are nuggets of fascinating philosophical questions. One fundamental problem was that the dinosaurs of Jurassic Park were artificial creatures. They are artificial because of modifications made to their bodies. This gave rise to all sorts of problems and made them inherently unstable.

“You don’t know for sure?” Malcolm said, affecting astonishment.

Wu smiled, “I stopped counting,” he said, “after the first dozen. And you have to realize that sometimes we think we have an animal correctly made—from the standpoint of the DNA, which is our basic work—and the animal grows for six months and then something untoward happens. And we realize there is some error. A releaser gene isn’t operating. A hormone not being released. Or some other problem in the developmental sequence. So we have to go back to the drawing board with that animal so to speak.” (Jurassic Park p. 111)

One example of genetic modifications built into the recent ancient-future and reformational-catholic churches is the absence of the episcopacy. This is no mistake. To adopt an episcopal structure would mean surrendering congregational autonomy so precious to so much of Evangelicalism. In this sense they are still genetically Protestant. Their clinging to Protestant church structures fundamentally separates them from the early Church founded by the Apostles. The bishop was integral and fundamental to the early Church. Ignatius of Antioch, a student of John the Apostle and the third bishop of Antioch, stressed the importance of obeying the bishop (see Letter to the Smyrneans VIII, IX).

Where the bishop is present, there let the congregation gather, just as where Jesus Christ is, there is the Catholic Church. Without the bishop’s supervision, no baptisms or love feasts are permitted.

Yet the libertarian strand in Protestant theology will not allow for bishops in the historic sense. Many Protestants by reading only the Bible and ignoring the early church fathers end up projecting their Protestant bias onto church history. But such an omission would be like a historian writing a book about ancient Rome with no mention of the Caesars! Or a law professor teaching a course on American jurisprudence with hardly a mention of the Supreme Court.

Another quandary in the Protestant quest for the early Church is whether one could actually bring it back or just end up with a caricature. A similar quandary existed for the scientists in Jurassic Park who had never seen a living dinosaur from the Mesozoic era.

Grant said, “How do you know if it’s developing correctly? No one has ever seen these animals before.”

Wu smiled. “I have often thought about that. I suppose it is a bit of a paradox. Eventually, I hope, paleontologists such as yourself will compare our animals with the fossil record to verify the developmental sequence.” (Jurassic Park p. 114).

The paradox here is whether these reconstructed dinosaurs were really dinosaurs or something else. All that the scientists had to go by were fossils, not actual living dinosaurs from the Mesozoic era. Similarly, for Protestants all they had to go by were ancient patristic texts but no living church tradition that goes back to the early Church. This leaves them guessing as to what the early Church must have been like.

Similarly, there is a tension between people who have little patience for the deep questions and just want to get things done.

Hammond sighed. “Now, Henry, are we going to have another one of those abstract discussions? You know I like to keep it simple. The dinosaurs we have now are real and—“

“Well, not exactly,” Wu said. He paced the living room, pointed to the monitors. “I don’t think we should kid ourselves. We haven’t re-created the past here. The past is gone. It can never be re-created. What we’ve done is reconstruct the past—or at least a version of the past.” (Jurassic Park pp. 121-122)

Lacking a living tradition that goes back to the Apostolic Church, Protestants end up having to reconstruct the early Church as they best understood it to have been. The Jesus Movement of the 1970s had house churches where people sat on the floor, played guitars and sang praise songs, and everyone with a Bible in their hands. More recently, Evangelicals have discovered the writings of the early church fathers and are seeking to incorporate these discoveries into their congregations: reciting the Nicene Creed, celebrating the Eucharist weekly, vestments for the clergy, candles and incense. Not being part of a living tradition they end up creating a “version of the past” trusting God to bless their sincere efforts to return to the early Church. It is like lost travelers seeking to find their way home without knowing where home is on the map.

The Lost World

The Lost World Scenario

An alternative scenario can be found in another book written by Michael Crichton, The Lost World.

“No, no,” Levine said earnestly. “I’m quite serious. What if the dinosaurs did not become extinct? What if they still exist? Somewhere in an isolated spot on the planet.” (Lost World p. 5)

The Protestant view of history assumes that there once was an apostolic Church but it no longer exists today. But Protestants and Evangelicals need to ask the question: What if the apostolic Church still exists today? What if there was a church where the errors of the papacy were avoided? What if that church was within driving distance today?

For Evangelicals Eastern Orthodoxy is a Lost World. Many Protestants and Evangelicals drive by these funny looking ethnic churches with strange names unaware of these churches’ connection to the early Church. The estrangement of the Great Schism of 1054 resulted in Western Christians, both Roman Catholics and Protestants, not being aware of Orthodoxy’s existence and its distinctive approach to doctrine and worship. The Protestant Reformers’ bitter struggle against medieval Catholicism gave Protestants a severe astigmatism that skewed their understanding of church history. Protestants came to view the early Church through the prism of Catholicism imagining the Apostolic Church to be part a lost past. But while the Protestants of the 1500s can be excused for having a distorted perspective on church history, the situation is quite different today. Many Protestants in recent years are learning about the early church fathers and are having a firsthand encounter with Orthodoxy.

This is why the first visit to an Orthodox Church is often such a surprise for many Evangelicals. Orthodoxy represents what many Protestants are seeking after, the early Church before Roman Catholicism. The Orthodox Liturgy is part of living tradition that goes back to the days of the Apostles. At first glance many would find this hard to accept especially the icons, the elaborate liturgical ceremonies, and ornate vestments worn by priests. All these are so radically different from the austere minimalism that mark Reformed, and especially, Puritan worship, or the exuberant expressiveness of charismatic worship.

Images in Dura Europos Synagogue 3rd century

But when approached from the standpoint of the Old Testament pattern of worship transformed by the New Covenant of Jesus Christ, the Divine Liturgy makes perfectly good sense. The vestments worn by Orthodox priests are patterned after those worn by the Old Testament priests. If Jesus Christ is the Passover Lamb who takes away the sins of the world then it makes sense to view the Eucharist as the culmination of the Old Testament sacrificial system. A careful reading shows that icons have a biblical basis in the Old Testament (Exodus 26, 2 Chronicles 3). Recent archaeological findings have shown that early Jewish synagogues had images on their walls. All this explains why a conscientious re-reading of Scripture and an open minded study of church history have led thousands of Protestants: pastors, professors, devout laymen to the conclusion that the Orthodox Church is indeed what it claims to be: the very Church founded by Christ himself, not some later knock off imitation. Visit Journey to Orthodoxy.com

Testing the Lost World Hypothesis

Protestant ecclesiology assumes a major discontinuity in history. Protestant church history is based on the idea that there once was a pure and apostolic Church but that early Church fell into spiritual darkness. It was not until the Reformation that Martin Luther recovered the Gospel and spiritual light returned to Europe. Protestants believe that using the principle of the “Bible alone” they will be able to reform (reconstruct) the Church as it was meant to be. These assumptions are foundational to defining Protestant identity. The Protestant view of history is crucial for explaining why Protestants are different from Roman Catholics (they follow the ‘Bible alone’) and why they remain separate from Roman Catholics (they have Gospel in the pure form of justification by ‘faith alone’).

Orthodoxy presents a significant challenge to the Protestant paradigm of church history. It is the Lost World that did not become extinct. Orthodoxy claims a historical continuity that goes back to the first century but it looks so different from what Evangelicals imagine the early Church to have been like. Evangelicals can test Orthodoxy’s claim to historical continuity by studying the church of Antioch.

Many Evangelicals greatly admire the Apostle Paul the great missionary but only a few know the name of his home church. Every missionary has a home church from which they were sent. According to Acts 13:1-3, Paul received his missionary calling at the church of Antioch. In this brief passage we learn during the Liturgy the Holy Spirit directed that Paul and Barnabas be set aside for missionary work. The Church of Antioch – the Apostle Paul’s home church — continues to exist to this day. The current Patriarch of Antioch, John X, can trace his apostolic succession back to the first century. The Antiochian Orthodox Archdiocese of North America, which received two thousand Evangelicals into Orthodoxy in 1987, has direct ties with the Apostle Paul’s home church. This is a spiritual lineage that any Evangelical would be proud to have!

Another way an Evangelical can test the Lost World hypothesis is by tracing the form of worship used in the church of Antioch. We learn from that same passage (Acts 13:1-3) that the worship in Antioch was liturgical worship. The Greek word for “worshiping the Lord” (NIV) or “ministered to the Lord” (KJV) is “leitourgounton” from which we get “liturgy.” This is why Orthodox Christians refer to their Sunday worship as “the Liturgy.” The worship of the first Christians in Jerusalem was liturgical. This can be seen in Acts 2:42 which referred to the Liturgy of the Word (the Apostles’ teaching) and the Liturgy of the Eucharist (the breaking of bread). On most Sundays we use the fifth century Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom and about ten times a year we use the fourth century Liturgy of St. Basil the Great. These liturgies which were inherited or passed on from the bishops before them are part of the Tradition of the ancient Church. In October we use the first century Liturgy of St. James. The liturgy was named after the Lord’s brother who served as bishop of Jerusalem and in that capacity presided over the first church council recorded in Acts 15. This historical continuity in Orthodox worship stands in stark contrast with the rapidly evolving forms of worship in Protestantism and Evangelicalism. The historic pattern of worship is pretty much lost in much of Evangelicalism. In the more progressive churches the order of worship changes from week to week depending on the decisions made by the praise and worship team. In the more ‘traditional’ Protestant churches the order of worship found in the back of the hymnal is never used by the congregation.

A third way an Evangelical can test the Lost World hypothesis is by tracing the form of church government. The early form of church government was episcopal – rule by bishop. Ignatius of Antioch, the third bishop of Antioch and a disciple of the Apostle John, wrote a series of letters on his way to martyrdom in Rome in 98 or 117 about the importance of obeying the bishop. In his letters he exhorted people not to celebrate the Eucharist (Lord’s Supper) apart from the bishop (Letter to the Smyrneans VIII and IX). All this is so different from Evangelicalism which favors congregational autonomy or the Presbyterian classis. Protestants may be averse to the episcopacy due to their opposition to the Roman Catholic Church but the fact remains that the episcopacy was the norm in the early Church. The notion of a universal papal supremacy was a distortion that Protestants rightly objected to. Orthodoxy also object on the basis that papal supremacy is contrary to Tradition. This supports the Lost World hypothesis that the Orthodox Church is the same church as the early Church.

Jurassic Park

GMO Churches?

Robert Webber’s ancient-future worship movement and Peter Leithart’s reformational-catholicism are examples of a GMO churches. “GMO” refers to “genetically modified organism.” Like the Jurassic Park scientists working to re-create dinosaurs, contemporary theologians and pastors are seeking to re-create the ancient Church based on their research. Their motives may be sincere but the means they used are highly problematic. Sola Scriptura, because it denies Holy Tradition a regulative function in the interpretation of Scripture, has given rise to all sorts of novel doctrines and worship practices resulting in ever multiplying church divisions. As a result there is no integrating center for Protestantism despite their longing for the unity of the ancient Church.

A carefully guarded and transmitted Holy Tradition gives Orthodoxy doctrinal stability and historical continuity that Protestantism never had. The transmission of Holy Tradition is done through apostolic succession, one bishop passing on the Faith to his successor. Another significant factor has been Orthodoxy’s practice of closed communion — only those who are Orthodox and in good standing can partake of the Eucharist. The Eucharist in addition to being the source of unity for Orthodoxy also protects the Orthodox against heterodox innovations. To use an analogy from biology, closed communion prevents unchecked interchange of unwarranted ideas and practices.

All this confronts sincere and serious Evangelicals with a profound question: Is the early Church of the Apostles really gone for good or is it still alive here and now in the Orthodox Church? This in turn presents them with a crucial choice: Do I place myself within the life and communion of the Church that has roots going back to the Apostles – or do I persist in the quest to reconstruct the early Church? In recent years thousands of Protestants and Evangelicals have completed their quest for the ancient Church by taking the bold step of joining the Orthodox Church. Interested readers can learn more about these journeys to Orthodoxy by checking out the titles and links recommended below. The ancient Church founded by the Apostles has never gone away, it is here in the Orthodox Church. By the mercies of God, we bid you: “Come and see.”

Robert Arakaki

Recommendations

Becoming Orthodox by Peter Gillquist

Thirsting for God in a Land of Shallow Wells by Matthew Gallatin

Facing East by Frederica Mathewes-Green

Orthodox Worship: A Living Continuity With the Temple, the Synagogue and the Early Church by Benjamin Williams

The Orthodox Church by Kallistos (Timothy) Ware

The Orthodox Way by Kallistos (Timothy) Ware

Blog: Journey to Orthodoxy

Blog: Letters on Orthodoxy

Blog: Liturgica

Recent Comments