On 29 March 2011, Robin Phillips posted an intriguing and disturbing article, “Are Calvinists Also Among the Gnostics?” in which he discussed the tendency to Gnosticism in Reformed theology. More recently in December 2011, he posted, “A Critical Absence of the Divine: How a ‘Zero-Sum’ Theology Destroys Sacred Space” in which he discussed how this Gnostic tendency has impacted Reformed worship and church architecture.

This is not just Phillips’ own interpretation of Calvin and Reformed theology but a synopsis of an emerging discussion among scholars. He is careful to note that Calvin himself sought to maintain a dialectical balance between his spiritualizing tendency by putting a premium on secondary means. It was Calvin’s spiritual descendants (Jonathan Edwards, B.B. Warfield) who took this spiritualizing tendency further than he intended.

Symptoms and Diagnosis

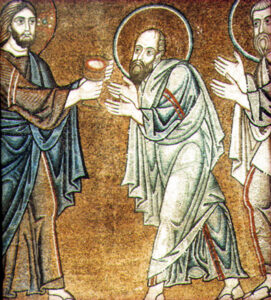

The gnosticizing tendency is manifested in the minimizing or denial of secondary causation and the emphasis on divine immediacy. This is the notion that material means, e.g., sacraments, are irrelevant or interfere with the divine economy. Divine immediacy takes place by means of the Word of God. This has been extremely consequential for Reformed Christianity. It has resulted in the denial of sacred space, stained glass, gothic arches, crosses, altars, the church calendar. It explains the widely known iconoclasm of Reformed theology. It also accounts for Calvin’s aversion to annointing a sick person with oil for healing even though the practice is taught in Scripture. Reading this has helped me to understand why so many Reformed churches have a stark austere beauty. The purpose of Reformed architecture is to support the primacy of Scripture proclaimed in the sermon. This world view has ramifications for the rest of life, some of them quite surprising. It has led to Reformed pastors telling parents that all their good works as parents to raise believing children are of no lasting benefit.Robin Phillips’ argument is fairly complex. It is recommended that visitors go to Phillips’ site directly and read the posting directly. Below are excerpts from the two postings to assist the reader.

Excerpts from:

A Critical Absence of the Divine: How a ‘Zero-Sum’ Theology Destroys Sacred Space

The ancient Gnostics didn’t know about game theory, but they tended to treat God’s glory as if it was a zero-sum contest between God and creation. The glory of God, they seemed to think, could only be maintained by denigrating the created order, or at least denying that anything of spiritual value could be derived from the creation. In fact, the Gnostics adopted such a low view of the material world that they ended up denying that Christ even had a physical body. It would be beneath the dignity of the Divine Being, they thought, to have his glory mediated through material flesh.

In this article I will suggest that one of the temptations of the reformed theological tradition has been a tendency to operate with similar ‘zero-sum’ assumptions. What I am calling a ‘zero-sum’ approach (though the economic metaphor is only a metaphor and should not be pressed too closely) manifests itself in a number of ways, not least in the tendency to view the glory of God and the glory of creation as if they exist in an inverse relationship to each other, so that whatever is granted to the latter is that much less that is left over for the former.

In their polemics against the proliferation of images within Roman Catholic worship, both the English Puritans and the Continental Calvinists had a tendency to veer towards the type of disembodied Gnosticism that they would have discountenanced in any other context. The result has been to denigrate the created order and to create a false dichotomy between the spiritual and the physical.

I have sometimes heard extraordinary language is used to denounce the efficacy of good parental works from teachers who think that if our works can lead to godly offspring then we are depending on ourselves rather than God. Since godly parenting is ‘impossible’ and ‘beyond us’ and ‘outside our ability’ (all concepts that I have heard invoked) the solution is not to parent by works but by ‘faith.’

Are Calvinists Also Among the Gnostics?

Earlier in the year as I was reading history for my doctoral research with King’s College, London, I was struck again and again by just how Gnostic so much of the Calvinist tradition is, especially Calvinism of the Puritan variety.

The churches that followed in Calvin’s wake would be marked by this de-physicalising influence and the corollary tendency for the cerebral to swallow up the sacramental, for the invisible to absorb the incarnational.

The result of this disenchantment with liturgical approaches, together with the notion that worship was first and foremost a matter of instruction in the Word of God, dovetailed with the assumption among reformed communities (though not among those of the Lutheran and Anglican traditions) that for worship to be ‘spiritual’ it must be what they called ‘simple’ in the sense of being disencumbered with the trappings of materiality.

My Response

Overall, I agree with what Robin Phillips had to say. He raised issues that I had never thought of when I was a Reformed Christian. I think the concerns he raised are important and deserve to be addressed by other Protestants. In my comments below I do two things: (1) I point out areas where Phillips may have been too hard on Calvin, and (2) I raise implications of Phillips’ argument that he may have overlooked.

Where Phillips May Have Been Too Hard on Calvin

One missing element in Phillips’ analysis is Calvin’s emphasis on our mystical union with Christ and the importance of the Real Presence of Christ in the Lord’s Supper for our life in Christ. These important themes have been suppressed or glossed over by certain of Calvin’s spiritual descendants. This is an element that the Mercersburg movement has sought to recover and reintroduce to the church with limited success.

Overlooked Implications of Phillips’ Argument

One missing element in Phillips’ postings is a discussion of the role of the pastor and the sermon in Christian worship. If one wishes to take the denial of secondary causation to its logical conclusion one would need to deny the need for sermon in which Scripture is explained and interpreted by the pastor. This mediation consists not just in the sermon on Sunday morning but also the pastor’s standing with the church at large. In the Reformed tradition the pastor occupies an office of the church; as part of the learned clergy he seeks to apply the best scholarship to his exposition of the text; and he seeks to speak the word to the situation of the flock under his care. Thus, the ordained minister serves several critical mediatorial functions in the life of the church. Without this understanding one becomes vulnerable to the direct ‘word of God’ given in certain Pentecostal circles.

Another missing element is the neglect of history as a consequence of gnosticism. Much of Reformed theology understands theology as consisting of timeless truths found in Scripture. The notion of a mediated faith tradition is either derided or subordinated to the divine revelation in Scripture. This tendency to ahistoricism gives rise to an uncritical acceptance of innovations of recent and a minimizing a solidarity with the historic church.

A possible implication that can be drawn from Phillips’ argument is that the Gnostic tendency in Protestant theology may account for the exuberant worship in Pentecostalism and the mega churches. Early Gnosticism had two opposite, seemingly contradictory manifestations: (1) the ascetic form that denigrated the body by eschewing food and sex, and (2) the libertine form that indulged the desires of the flesh in order to liberate the soul.

Possible Remedies

If Phillips is right in his diagnosis of a Gnostic tendency running through Reformed theology, what are the remedies available? There has emerged in recent years a reaction to the disembodied approach to the Christian faith.

The focus of this posting is to present a remedy for the ills described by Phillips. Below are some options available to those troubled by the Reformed tradition’s dualistic tendencies with my observations about the feasibility of the option presented. I will start of with the options that are closer to home for Reformed Christians before looking at more radical alternatives.

Mercersburg Theology. In recent years there has emerged in Reformed circles a renewed interest in Mercersburg Theology with its emphasis on the Eucharist, the church fathers, and church history. Among the proponents are Keith Mathison, Jonathan Bonomo, and W. Bradford Littlejohn. Keith Mathison’s Given For You attempts to make the Eucharist the focus of Sunday worship. The appeal of Mercersburg Theology lies in the fact that it is a form of high church Calvinism rooted in the theology of John Calvin and Continental Reformed theology. One can be “Catholic” and “Reformed” at the same time just by working with Reformed sources. The weakness of Mercersburg Theology is that it has had little impact on church life. I expect that the current interest in Mercersburg Theology will in time be forgotten. The ephemerality of Mercersburg Theology can be seen in its absence in the United Church of Christ, the one denomination with direct ties to Mercersburg Theology.

Ancient-Future Worship and the Convergence Movement. Examples of the ancient-future worship can be found in Thomas Oden and Robert Webber. They have advocated a return to a more historically grounded and liturgically approach to worship and theology. While Oden remained a Methodist, Webber left his Baptist roots to become an Episcopalian. The ancient-future movement is diverse in composition and eclectic in its method. This eclecticism can be seen in the fact that rather than affiliate with one of the historic traditions, many ancient-future evangelicals on their own initiative appropriate elements from outside traditions. The best example of the convergence movement is the Charismatic Episcopal Church which seeks the blending or convergence of three steams: Evangelicalism, historic Anglicanism, and the charismatic renewal. For a conservative Reformed Christian the challenge here is the postmodern eclecticism and a free wheeling independence unchecked by historic tradition.

Ancient-Future Worship and the Convergence Movement. Examples of the ancient-future worship can be found in Thomas Oden and Robert Webber. They have advocated a return to a more historically grounded and liturgically approach to worship and theology. While Oden remained a Methodist, Webber left his Baptist roots to become an Episcopalian. The ancient-future movement is diverse in composition and eclectic in its method. This eclecticism can be seen in the fact that rather than affiliate with one of the historic traditions, many ancient-future evangelicals on their own initiative appropriate elements from outside traditions. The best example of the convergence movement is the Charismatic Episcopal Church which seeks the blending or convergence of three steams: Evangelicalism, historic Anglicanism, and the charismatic renewal. For a conservative Reformed Christian the challenge here is the postmodern eclecticism and a free wheeling independence unchecked by historic tradition.

Anglicanism. A number of Protestants and Evangelicals see in Anglicanism an appealing mixture of liturgical worship, historic tradition, and ordered church life. Unlike the previous option, the Anglican option is more solidly rooted in a defined historic tradition and has a canon of theological writings: Nicholas Ridley, Hugh Latimer, Richard Hooker and William Laud. The Anglican tradition possesses a certain stability with its tradition of using a normative prayer book for its worship life. While the Anglican tradition allows for a more embodied approach to worship and church life, it is currently in a state of disarray as a result of the current apostasy in the Episcopal Church.

Roman Catholicism. A number of Protestants, even Reformed Christians, have abandoned Protestantism and “crossed the Tiber River.” While the Roman Catholic Church is an embodied form of Christianity, becoming Roman Catholic would be a drastic cure for those seeking a remedy for Calvinism’s gnostic tendencies. One major issue for a Reformed Christian is the jettisoning of sola scriptura for the infallibility of the Papacy. While Roman Catholicism does take an embodied approach to faith, its organizational life seem to be heavily influenced by a bureaucratic and legalistic ethos. A Reformed Christian thinking of becoming Roman Catholic would do well to take a good hard look at the Great Schism of 1054 and ask if Rome did the right thing in breaking away from the other historic patriarchates of Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem.

Eastern Orthodoxy. Long ignored and overlooked by Protestants, one of the biggest surprise in recent years is Orthodoxy’s rapid growth as growing numbers convert to Orthodoxy. Long regarded as an ethnic denomination, Orthodoxy is in the process of becoming an American church. The appeal of Orthodoxy lies in its historical rootedness and its mystical/organic approach to worship and church life. Orthodoxy’s emphasis on the Incarnation of Christ and its implication for all of life present a deep cure for any gnostic tendency one may have. Becoming Orthodox will not be easy for a Reformed Christian, it will require giving up the Scripture over Tradition paradigm that underlies sola scriptura for Scripture in Tradition paradigm.

Finding the Right Remedy

These are confusing times. There are many spiritual pitfalls for unwary Christians. Robin Phillips relates that he and his family were at one time members of a crypto-Gnostic group. They found spiritual growth and healing in the liturgical life of an Anglican parish. Soon after, they affiliated themselves with a Reformed church where they heard fierce denunciations of icons and liturgical symbolism by James Jordan. In another posting, “Aids or Idols? The Place of Images in Worship” (posted 3 October 2010) Phillips presents a reasoned and Scriptural defense of the use of icons in Christian worship. I suspect that the Anglican via media which enabled him to take an inclusive and reasonable approach to the use of icons was broad enough to allow him to become a Calvinist. Phillips closes this posting with a question for his readers to ponder.

Further, if our practice implies that colors, symbols, gestures, smells and three-dimensional objects are inappropriate for the house of the Lord and must be reserved for “secular” occasions like birthdays, parades, weddings and Christmas banquets, then are we not driving a wedge between the deepest human yearnings and the God who made them? Are we not reinforcing the myth that Christian truth should be kept unbodied – a myth that has had enormous implications for how modern evangelicals understand the meaning of “kingdom of God” and has virtually eliminated any concept of Christendom from contemporary Protestant consciousness?

If Gnosticism’s toxic influence can be discerned in Reformed theology, what is the appropriate remedy? What remedy does Robin Phillips propose? I appreciate his reasonable and open minded approach to the issues, but how do we stop the dread disease of Gnosticism? He seems to be advocating via media, but is the Anglican via media sufficient to defeat this pernicious spiritual disease? Or do we need stronger medicine along the lines of Orthodoxy?

Gnosticism is dangerous spiritually because it makes the individual believer independent of the Church and divorces faith from action. The best cure for a religious tradition weakened by implicit gnosticism is not a system of doctrine that denounces the gnostic heresy but rather an orthodox faith embodied in a Christian community. An embodied faith community will be marked by a common Eucharistic worship, a shared universal confession of faith, and a leadership that follow the teachings of the apostles. Irenaeus of Lyons in his classic apologia against Gnosticism: Adversus Haereses (Against Heresies) put forward two identifying for the true Christian Church: catholicity and apostolicity.

The Orthodox Church offers strong protection against Gnosticism through its holistic understanding of Christianity as the Tradition of Christ lived out by the Church, the body of Christ. Orthodoxy’s strongest defense against Gnosticism lies not in the Liturgy, icons, holy days, priests wearing vestments, creeds, and prayer books but in Holy Tradition. A church can have all the listed items and not be a capital “O” Orthodox Church. Orthodoxy is relational; one is linked to the Church Catholic through the Eucharist and one is linked to the Apostles through apostolic succession via the bishop. The theological method of Orthodoxy is the reception of Apostolic Tradition, not the negotiation of competing extremes, e.g., low church Evangelicalism versus high church Anglo-Catholicism. The classic form of sola scriptura combined with the regulative principle is quite compatible with the rich liturgical and aesthetic traditions of Anglicanism and Lutheranism. But even then there is fundamental divide between them and Orthodoxy — Holy Tradition. So long as one holds to sola scriptura one cannot be an Orthodox Christian, one remains a Protestant. Sola Scriptura because it denies the binding authority of Tradition is vulnerable to being reinterpreted and renegotiated opening the way for doctrinal innovation or doctrinal drift. Becoming Orthodox is indeed strong medicine but let us keep in mind Ignatius of Antioch’s teaching that the Eucharist is the “medicine of immortality” received from the bishop, the true successor to the apostles:

…so that you obey the bishop and the presbytery with an undisturbed mind, breaking one bread, which is the medicine of immortality, the antidote that we should not die, but live for ever in Jesus Christ (Ignatius of Antioch, Letters to the Ephesians 20:2).

Robert Arakaki

See also:

Robin Phillips – “8 Gnostic Myths You May Have Imbibed”

Robert Arakaki – Irenaeus of Lyons: Contending for the Faith Once Delivered

I think it is funny that Robin can give well-articulated critiques of the Reformed tradition, and the detractors on your site commend his work, but when you quote Robin they get angry at you!

LOL Baroque! Yep they do, don’t they. Perhaps it’s because Robert refuses to hold these articles and conversations at academic arms’ length as if such matter were mere interesting curiosities?

Thanks Robin for an extraordinarily penetrating critique of developed Calvinism. Thanks also to Robert for your critique of Robin.

Permit me to ask two equally disturbing questions . . .

In the light of the outcome of the 1672 Council of the Jerusalem Patriarchate held in Bethlehem, and the Confession of Dositheus and the Acts of the Council of Jerusalem:

1) Did this Council etc in 1672 in some way “anticipate” Robin’s observations, and

2) Should we revisit this Council etc in the light of Robin’s critique and add yet another ground for concern about Calvinism as expressed at this Council?

I do not pretend to have all the answers to these two, but I believe they may have some bearing on this discussion. I simply pose them to move the discussion along with Conciliar input.

John,

I don’t know if the Confession of Dositheus’ anticipated Robin’s critique of Calvinism. The task of the Council was to evaluate Reformed theology which they did and concluded that it was incompatible with Orthodoxy. I don’t see any need for the Orthodox Church to look into Reformed theology again. What I did in my blog posting was to accept what Robin wrote as valid and focus my attention on the possible remedies. I’m trying to take a positive and constructive approach in the OrthodoxBridge. Thanks for raising an important question.

Robert

Robert, thanks for this.

Are we not seeing here a distinction between:

# Fide quarens intellectum, and

# Fide quarens orationem?

In the manner of an Ecclesiastical Philosophy 302 question:

“Compare and contrast these two, and locate the Developed Calvinism as present today in the continuum between these two axis nodes, especially with respect to both the Sermon and the Eucharist”.

Honestly, I believe this postmodern category of “Gnostic” may be a bit overused. It’s easy to criticize Reformed theologians over the lack of a full-blown understanding and working out of the gospel in their lives from the standpoint of merely reading about them or their works (an odd thing for a PhD candidate in an English university to do given the abstract nature of that sort of vocation). I’m not sure such a critique tells the whole story or fully rises to the challenge. It’s not like the critique stands from a vantage point which would allow us to see how the Reformed lived these things out except from what we can read. In other words, it’s a dramatically incomplete critique. The nation America would not be what it is, for example, without Protestantism.

Perhaps we can talk about Gnostic trends within each of the streams Robin notes, but I can also point interested readers to individuals and communities that very much bucked the trend Robin is writing against. And, it’s not really Gnosticism in its original form that Robin is criticizing anyway. It seems that every Christian communion has their own eccentricities when you take the time to look closely enough. I’m quite sure we could do the same with Orthodoxy and to pretend that Orthodoxy is the required corrective is to pass lightly over its own problems and not exactly being honest.

I think Kevin has a valid point here. Not all Reformed folk need hit the panic button and convert to Orthodoxy in a heated rush. (Thankfully, I’ve never met an Orthodox Priest, or even a convert who encouraged such a thing…they’re typically very passive/patient proselytizers.) This blog is a calm dialogue (usually)…and not all ‘Reformed’ are equally guilty of gnostic tendencies…so Kevin is right to caution against lumping all Protestants in the same 2nd century bucket of Gnosticism. I think Robert would agree here too.

But neither should we dismiss Robins’ salient and potentially potent points here about the ontology of the material creation. Significant implications likely follow. Matter matters. It can, and does mediate the grace of God to man. BB Warfield was dead wrong (maybe Jonathan Edwards too). Without revisiting anthropology/the doctrine of Man…or the Christological issues surrounding the Incarnation, Robin points to his making a Protestant defense of Icons. Thus, IF Robin is mostly right, per our Protestant-Gnostic regard for matter/Creation & sacred space — then our material Ontology at this point IS “mostly wrong” & Orthodoxy’s (or someone?) mostly right — Divine Grace IS mediated to man thru matter…and this opens a host of other issues (anthropology/Christology) not to be tritely waved off, or dismissed. I’ll stop here but just gotta ask….what, pray tell, does “The nation America would not be what it is, for example, without Protestantism.” mean? Sorry Kevin, but I couldn’t let that one slide! 🙂

An acquaintance of mine in some (somewhat) celebrated lectures on Protestant superiority proudly claimed that Protestantism is superior as seen by the superior standing of America today.

The American stockmarket crashed a few weeks later and the “people” elected Obama.

David,

I agree that we shouldn’t lump Protestants with the second century Gnostics. However, there are modern day Protestants who deny the importance of matter just like the early Gnostics. In my article on Irenaeus of Lyons I mentioned that a minister attending a conference at the Pacific School of Religion denied the importance of believing in Christ’s bodily resurrection. I also pointed to the Episcopal Church’s anything-goes approach to sexual ethics which bears strong resemblance to second century Gnosticism. While they are extreme examples they ARE part of the broad spectrum of Protestant Christianity with conservatives like Michael Horton, Keith Mathison, John MacArthur on the other end.

But my intent is not to bash Protestants, especially Reformed Protestants, but to engage them in dialogue. What I found so striking about Robin Phillips’ article is that it seems to explain well the stark austerity so characteristic of Reformed Churches. The same cannot be said of Anglican or Lutheran churches. So one has to wonder WHY is there this strong similarity among Reformed architecture and what is the theological significance of Reformed architecture? I think Robin has given us an astute analysis/diagnosis. I then focused my blog posting on finding the appropriate, effective remedy. It seems that for Kevin it is just a wart but for others it is a symptom of a malignant tumor.

Robert

For once, Robert, I’d love to see you engage in an effective and realistic criticism of your own communion instead of act like Orthodoxy is the answer to every ill presented to us elsewhere in the church. To pretend that Orthodoxy does not have equally problematic issues is whitewashing the walls of your churches.

I actually agree with some of Robin’s criticisms (though again I think the concern and diagnosis is somewhat overblown), but the solution is not to think the grass is greener on the other side. The solution is real repentance and then continued faithfulness to God in every area of our lives.

Kevin,

I don’t think anyone here thinks that Orthodox doesn’t have it’s own problems. I’ve heard Orthodoxy described as a leaper colony and in many ways it is. But here’s the thing: The cure to Orthodoxy’s woes is a return to the Apostolic deposit given to us. In essence, this is the cure for all of Christendom’s problems whether Reformed, evangelical, RC, etc. Some have a longer road to travel than others. Roman Catholics have less to travel than the Reformed (Magisterial) and the Reformed have less to travel than the most evangelicals/Pentecostals. There’s no denying that our communions are plagued by sin. But the answer isn’t revolution or reform but turning back (repenting) towards that which was delivered to all the saints.

I have no doubt that we disagree over the cure to Christendom’s problems . But the answer, again, is the same. We must return to that which was given to us in the Apostolic Tradition.

Why should he critique Orthodoxy when that is not the purpose of his website? There are places for that amongst the Orthodox. It begins in our parishes and extends to the whole Orthodox community, locally and globally. I’m sure there are even blogs that may or may not be solely devoted to that topic. Many do make mention of it from time to time. We aren’t hiding this information, at least so far as I know. David, from Pious Fabrications, has made mention of some issues of Orthodoxy in America on his website and books by Fr. Alexander Schmemman (Lent, the Journey to Orthodoxy, for example) speak of some of Orthodoxy’s flaws. In each, the cure is always the same. Return to the Apostolic Deposit.

I don’t think I need to say this but here it is. My blatant admission that my Church is plagued by sin, including my own. And here is also my admission that the cure is to do what Christians must always do in all times and in all places: guard the Deposit of Faith, keep it undefiled, and when I turn from it and from God, I must turn back to it and to God, for it is God-given.

John

I will leave aside the considerations of christology for the moment because it’s an inherently difficult subject on any side of the question.

But, David, my point regarding America is that the Protestant role in its founding was not a matter of the sort of gnostic behavior Robin/Robert outlines here. We can see through the actions of the Reformed and the Puritans that the nation-building that took place in America during the Revolution and the earlier colonial period was most definitely a concrete and full working out of Reformed/Christian principles. As such it lays a warning sign at the door of the Reformed for those who would come and nail their own 95 Theses of Gnostic Considerations against All Things Reformed. And, such is only one example. I know Philip Lee’s work is popular in outlining some of these ideas about how bad Protestantism is, I’m just not completely sure the critique hits the mark as much as it should.

Kevin,

When you said “Reformed/Christian principles” what group did you have in mind? The Congregationalists in New England and New Jersey? The Presbyterians in the Mid-Atlantic and the South? The early Calvinistic Baptists in America? Who did you have in mind? Or are you just saying this just to say it?

Also, America is a mixed bag or hybrid of not only various forms of protestantism and in Maryland Roman Catholicism, but also enlightenment thought as well, and so the foundation of America is both Secular and protestant Christian. It’s simultaneously Barbaric/heathen and Christian……just like in Europe for Europe was never really truly/completely evangelized.

That’s an issue I’ve wrestled with for ten years. I used to hold to the Christian America thesis, but it has to be infinitely qualified to work. Certainly Patrick Henry and the Puritan era, but beyond that I can’t affirm it.

Even if the Constitutional founders weren’t Deists, most were Masons (which in my mind is infinitely worse, since Masons swear an oath to Lucifer; btw, Kevin, if you are looking for a critique of Orthodoxy, there you have it: Freemasons infiltrated the Greek World, and to a lesser extent the Serbs, after WWI).

And then there is the structure of the Constitution. It relies on a dialectical relation of oppositions, as argued by Patrick Henry.

While it pains me to praise Jim Jordan, he has a chapter in his book on creation that details American Calvinism’s Gnosticism. Of course, Jordan is a closet Hegelian, so he’s not entirely free from the charge.

There are bright moments in the Continental Reformed. Mathison’s work comes to mind (though he builds upon ambiguities in Augustine, so I find his argument unconvincing).

I remember that chapter in Jim’s book well…best chapter in the book. And I remember telling my friend that sections of the chapter sounded just like they came right out of my old “The Agrarian Steward” newletter! But I suspect I’m prone to self-flattery on such matters.

But I thought Robin’s article’s took Phillip Lee’s _Against The Protestant Gnostics_ and Jim’s chapter to a new level — pointing to and challenging our Ontology of Creation/materiality and our doctrine of Man pre & post Fall. And of course…such thing ultimately touch on Christology.

And no one has even broached the subject of Synergy & Mongergism as it relates to Robin’s “Zero-Sum” notions as they pertain to the glory & sovereignty of God?

I do notice that Mr. (Dr.?) Phillips emphasizes that the Gnostic leaning element in Reformed Christianity is the Puritan branch. I think that is important.

My church community, even though not technically part of the Puritan movement, is heavily influenced by their theology. We tend to have a constant war between those who want to “lean Dutch” (I am situated here) and those who are the “truly Reformed” (the Puritans). It is a frustrating set of battles. However, the Dutch-influenced, Kuyperian, Dooyeweerdian side is largely anti-Gnostic (although we call it “anti-dualist”). It is small, but it is there.

For what it is worth.

Russ

A very good article, and a fair critique by Robin, I think. I’m not sure he goes far enough though. While the original puritans were separatists who wanted to found a uniquely protestant nation in the new world, currently reformed christians are visibly retreating from that aspiration. Just this morning I was treated to still another sermon reminding us that the Kingdom of God does not come through political activism, but is an interior work of the Spirit, over each individual heart. Well duh. But the fact is, real conversion has a visible impact on a man’s life, his wife, his children and their society. The kingdom is like leaven, and it infiltrates and permeates our whole lives, not just our prayer closet and the bare walls of our churches.

So, I guess reading Robin’s critique made me want to shout ‘amen’… and also add that our gnosticism is also inherent in our cowardly refusal to take all things captive to Christ. Including Caesar; who Paul insisted was a ‘minister of God’. He is an underling, a servant of the Most High. Including health care. Including law. Including politics. Including environmental stewardship. Our churches, descended from Calvin, would be afraid to do what Calvin attempted in Geneva – the creation of a uniquely protestant christian culture and city. We’d be afraid to embark on the Mayflower and sign the Mayflower compact, and then bury many of our friends in the cold New England earth. We’re so gnostic we don’t even recognize that we’ve fenced the gospel out of our culture and politics, actively agreeing with secular God-haters that there ought to be a ‘wall of separation’ between the Gospel and any human endeavor that can’t be narrowly defined as a church. And we do this in the name of Christ, the King of all, and while we piously pray: ‘Thy Kingdom come, thy will be done, on EARTH as it is in heaven’.

Yeah, our gnosticism is clearly seen in our worship. It’s also preached in our sermons. And it’s resulted in the full-scale cultural retreat of our churches, in the land our fore-fathers built. It’s no wonder so many reformed are swimming the Tiber and investigating eastern orthodoxy. The Catholic churches still believe they ARE the Kingdom, the Israel of God, and they will rule and reign on the earth until Christ returns, and afterward as well, in the New heaven and new earth. Rome is still the largest single christian charity on the planet, and the Pope, whatever you may think of him, has a world-wide flock, 1 billion strong. Catholic churches have shaped empires and nations for 2000 years; deposing kings and establishing others, caring for the poor, and shedding blood in every age in civil disobedience to the wicked who have held power. Hungarian Catholics have recently enshrined pro-life policies in their new constitution. What have Protestants done in comparison? There are no pro-life protestant nations; only nations who used to be protestant and are now secular and atheist. The reformation has produced thousands of quarreling denominations, a permanent scattering of the Lord’s body, and a lot of pietist-gnostic preaching; all sound and fury, signifying nothing.

Rant over. Thanks Robert for another great article.

I think I like this Reformed Lurker! 🙂 And his rant is spot-on!

In my theological studies, I have noticed that Calvinists put more emphasis on “knowledge” of God than “faith” in God. This would put them more so in the Gnostic camp. Pure Gnostics would not trust their own faith since it comes from within a corrupted body. However, they would trust “secret knowledge” since it comes from a messenger from God. I see “election” in both Calvin denominations and Gnostic sentiments. Moreover, ancient Gnostics were consumed with the idea of salvation, which I also have witnessed in many Baptist traditions today. I have observed them praising salvation with less regard to the Savior, almost to the point of worshipping the gift. They have an overemphasis on instantaneous conversion due to revelations from God’s Word, which in turn makes them practice heavy evangelism. All that being said, I still would not call them Gnostics but Christians who have been influenced by that heresy as Christianity evolved over time.

Jeff,

Interesting insight! Oftentimes people have an unbalanced understanding of what it means to be saved. This reminds me of what Paul wrote in 1 Thessalonians 5:23: “May your whole spirit, soul, and body be kept blameless at the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ.” Essential to the Christian Faith is God saving our entire being.

Robert

Jeff,

On the one hand, I agree. But on the other hand, not having a strong emphasis on evangelism (mission?) seems to belittle the way Paul handled himself. What many evangelicals have historically practiced, though, is what I would call hit-and-run evangelism. An evangelism that assumes that taking your time is an unnecessary aspect of conversion and that discipleship is not a part of salvation, but the sort of “after” having been saved. This is where, I believe, there are major problems with that “point-of-conversion” theology.

But there are some clear abuses with a theology that is too focused on the process of salvation. So much inward focus can be had that there is not any real focus outward. What I mean is that people can be so concerned about their own salvation (so insecure) that they don’t care about the salvation of others. Should there not be some security in Christ that allows us to be others focused rather than self-focused? On the other hand, I do agree that we should “work out our salvation with fear and trembling.” It is so easy in discussing these things to get too one-sided in our explanations.

Prometheus, can you give examples of such “clear abuses?” Is this something you have experienced of the Orthodox? I wonder whether these are actually abuses that result from a focus on salvation as a process, or that are the result, instead, of a nominal or immature faith or lack of understanding about the real nature of that salvation.

I have never found an increasing awareness of my own need for salvation (moment by moment) did not also make me more acutely desirous of the salvation of others as well. It is perhaps instructive, but counter-intuitive for most Christians trained in western theological traditions, that the most devoted of the (supposedly) “naval-gazing” Hesychasts among us (our holy Orthodox monastic elders and elderesses) , cloistered and far removed from the world in their monasteries, are the ones who bear the most fruit in terms of inspiring repentance and faith in others–those people who come into contact with them through pilgrimage and retreat at those monasteries or by learning about their lives by reading their written works and/or their lives and words recorded for us by others. As St. Seraphim of Sarov, such a Russian elder, famously taught: “Acquire the Spirit of peace and a thousand souls around you will be saved.”

It seems to me there can be no truly effective sharing of the gospel apart from it becoming more and more evident in our own lives through the diligent working out of our own salvation (which is basically what the Saint meant by the statement “acquire the Spirit of peace” using a merchant’s analogy–he was the son of a merchant). Faith is more caught by others who experience our example and our life than taught explicitly by proclamation of words. The more we acquire the Spirit of Christ through working out our own salvation, the more we respond to the needs of others as He did and the more we long and labor in prayer and service for the salvation of others as well.

I fell in love with Jesus when I was a child and as a child and teenager that love overflowed in seeking to act in ways that honored Him and in talking about Him in a very natural way to my close friends. Without any agenda on my part (because I assumed they were already Christians), this natural overflow of my love for Christ resulted in my two best friends in high school quietly deciding they wanted what I had and committing themselves to seek God in a more personal way than what was up to that point for them nominal Christian faith. (I didn’t find out this was the case until a few years after we had graduated.) To this day they are both still committed believers active in their churches.

Soon after that time, though, the influence from the constant emphasis on outreach and evangelism as the whole purpose of God’s leaving us on earth after “saving” us in my Evangelical context led in my later teen years and through college and beyond to my getting involved in various evangelism-focused outreaches. I even served for two years as a short-term missionary on a university campus in Europe. By this point in my life, I was so busy trying to “reach and teach others” for Christ (often in ways that were far outside my comfort zone–I am a more quiet and contemplative person by nature), I had all but forgotten the love His grace had inspired in me. The forces of obligation and guilt ruled my life because of constant exposure to teaching that suggested if I wasn’t evangelizing, I might not truly know Christ at all or that I certainly wasn’t growing in Him as I should. (Talk about God’s work in and through me being derailed by insecurity and performance anxiety!) Later in my early 30s after I had burned out on the mission field and intentionally got off of that performance treadmill, I completed a survey on evangelism for a fellow church member who was also a journalist with a Christian magazine for an article he was writing. Of the 20-30 or so ways one could do outreach that were listed on that survey, I discovered that I actually had participated in all but one or two of them. But here’s the real kicker–when it came time to evaluate my effectiveness in terms of people making decisions for Christ, I could only score myself a zero in every single instance of those intentional and programmed outreach efforts in which I had participated. The only real fruit I could show in terms of actually replicating my faith was my two high school friends with whom I had no agenda other than being myself! It hit me like a ton of bricks that my heavenly Father didn’t want my works, He wanted me, and then He would do the rest. And so from Orthodox tradition and also from my own very personal experience, I find an emphasis on anything other than making every effort to find oneself really and truly experientially “in Christ,” derails the work of the Holy Spirit in our own life and, consequently, leaves us so spiritually sterile we have nothing in us that can infect others with real spiritual life and faith either.

In a paradox, an emphasis on Christian activism quashes the work of the Holy Spirit in the soul, while an emphasis on attentiveness to prayer and the inner spiritual life when the nature of this life is truly understood and when this is heeded leads to abundant spiritual fecundity.

Thank you Karen,

There is so much of what you are saying that I resonate with in my own life. In fact one of my greatest heroes in the faith is my uncle who quietly lived out his faith, raised his family, and was a nobody for Christ, while my parents are missionaries. I am not a missionary, and I have to trust that God has me where he has me for a reason.

The abuses I’m talking about have to do with the constant fear of one’s own salvation. I think, from what I see of what you have written, that your pursuing being “in Christ” has been out of a confidence in Christ rather than a fear of losing your salvation.

Not everyone has a call to evangelism in the way that Paul did. And he did have a call and a commission from the church.

So thank you for your reminder that we must pursue Christ and leave the rest to him. It is so odd that a theology that is so adverse to “works” emphasizes them so much (i.e. various groups of Protestantism).

I know that when I don’t have Jesus, I cannot share Jesus.

Thanks, Prometheus. I think that’s an astute observation about the disjunction between the teachings of Protestant theologies so adamant that “works” are not involved in our salvation, and the fact that they actually end up emphasizing works. I’ve heard many Protestants (and many from the most stringently “anti-works, pro-grace alone” camps), express very real fears about the possibility of “not really being saved,” after all, or of the possibility of losing their salvation through falling away because of struggles with sins (and sometimes depression/mental illness) in their own lives.

Perhaps it will also strike you odd that a tradition in which the embodiment of faith in the practices of faith is not separated from the concept of saving faith does not also result in the constant insecurity about one’s salvation of which you speak. It does not in my experience, because the focus is ever on the merciful character and saving power of Christ Himself, Who has “trampled down death by His own death” and is ever forgiving us and offering us His own life afresh in the Eucharist. His life must be continuously extended to us in grace or we will die, and that life tends to leak out of us because we are leaky, sinful vessels! Because we recognize the deceitfulness of our own sinful hearts and acknowledge the true freedom of our will as real, we know that even those formally in the Church can fall away and end up perishing. But we are also confident of Christ’s faithfulness and mercy and confident He will continue to work His salvation in us if we will just continue to show up and accept His grace given to us in so many countless ways in the life of His Body, the Church.

The topic of salvation is a mysterious one. There may not be a one-size-fits-all method. Of course there must be a one-cross-fits-all means, the cross of Jesus. Salvation is only possible with God’s grace and the atonement. However, God in His wisdom might prefer instantaneous conversion in some and process conversion in others, depending upon what actual Biblical knowledge a person has. If a person is raised in a Calvinist tradition, God may convince him that he has been saved upon his initial decision to accept Jesus as Savior. If a person is raised in a Wesleyan tradition, God may convince him that he has been saved by also making Jesus Lord of his everyday life. One is not orthodox in exclusion to the other. Both are right based on what knowledge the person has acquired about biblical salvation. God is happy whichever we choose to believe as long as it chooses Him and is open to God’s infinite wisdom in these matters. The trick is not to take pride in our understanding of salvation. If we go there as Christians and become so exclusive as to say “we are the only Protestants actually going to heaven”, then God will certainly humble us.

FWIW…this article Robert did awhile back contrasting Orthodox & Reformed “Discipleship” might be helpful here. It seems to me as former life-long protestant we saw ‘evangelism & discipleship’ as essential additions to the life and worship of the Church…while historic Orthodoxy seems to see both more as “results”…of it all being mixed up in the Sacramental Liturgy of the Church.

https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/orthodoxbridge/discipleship-orthodox-protestant/

Thank you, David. This was good to read again.

Karen,

I do not see a disjunction or really any paradox in the kind of church life you are speaking of. This is the same reason I don’t see it in Arminianism/Wesleyanism for the most part. Faithfulness is not separated from the content of the faith. The creeds are not separate from the life of faith lived. I, too, have never really feared losing my salvation, though I don’t believe in “eternal security.” But I think that sometimes the people who do believe in eternal security spend more time analyzing themselves and whether they are elect or not. 🙂 However, I don’t think all people are like you and I, even in the Orthodox tradition. Christ-focused rather than me or others focused is probably the best way to avoid either implosion or dissipation. Anyways. 🙂 Thanks again for your thoughts.

“Christ-focused rather than me or others focused is probably the best way to avoid either implosion or dissipation.”

Yes, indeed!

Interesting article. I have to confess as a Reformed Christian that I agree with its premise that there are Gnostic tendencies within the Reformed constituency – particularly relating to its more Puritan expressions. We have lost sight of the sacred and have developed an unhealthy attitude to the material. However, as recognised, there are some like Mathison who are addressing this issue.

An interesting question to raise at this point–and one I didn’t always raise–is that in saying that Nature is infused with the sacred (or whatever) is that we don’t risk “magic-fying” nature. The question can be phrased another way: what was originally wrong with nature, whether prelapsarian or postlapsarian is irrelevant, that it needs grace superadded to it?

I’m all for getting back to aesthetics (I believe in candlelit services because florescent lighting is deleterious to the eyes–scientific fact), but there are some crucial theological questions first.

***This is not just Phillips’ own interpretation of Calvin and Reformed theology but a synopsis of an emerging discussion among scholars.***

I do want to add that a lot of scholars today, even Roman Catholic ones, are challenging the old “Reformed = nominalism” thesis (granted, that’s not precisely his point in the above essay, though it is one in which you linked). Even those who are sympathetic to the critique (Hans Boersma) acknowledge that if it has any merit (and I don’t think it does), then it equally applies to the Roman Catholicism of the time. In fact, Gabriel Biel’s, the nominalist of the period, view of salvation is almost identical to all the semi-Pelagian expressions in most non-Reformed churches. It’s just a bit ironic that *the* nominalist of the time held a view of salvation that is radically at odds with the Reformation.

I think the risk of “magical” understandings of what it means that the sensible, material world is also sacred is another example of what happens when Orthodox teaching and practice gets run through the modern western philosophical paradigm. I can’t highly recommend enough Fr. Stephen Freeman’s little book, Christianity in a One-Storey Universe. It seems to me he does a very good job of clarifying the purpose and nature of the Orthodox practice of sanctifying space, time and material objects to reveal God’s nature and purposes for all things (among other things). All of the material in his book can also be found at his site, “Glory to God for All Things.”

https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/glory2godforallthings/2013/10/05/there-is-no-such-thing-as-secular/

https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/glory2godforallthings/2012/08/21/life-in-a-sacramental-world/

https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/glory2godforallthings/2009/02/05/living-in-the-un-holy-land/

You are quite right that some Medieval Roman Catholic scholastics (e.g., William of Occam, Thomas Aquinas) were also advocating nominalism or trying to synthesize it into their theological systems. This is an example of why Orthodox tend to view Roman Catholics as the “first Protestants” and also why they tend to see more commonality between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism that between any of the western traditions and the Orthodox.

Aquinas was not a nominalist (at least not in the Occam sense). He rejected some of the wackier forms of realism, but still believed in universals extra mente. This is an important point because key Reformers, Bucer and Vermigli, were older than Calvin and hailed from the Thomist-realist tradition.

Correction: Aquinas believed in universals in the mind, but in universals nonetheless.

Yes, Aquinas is an example of someone who was not purely a nominalist like Occam, but was trying to synthesize aspects of nominalism into his own system. I haven’t studied Aquinas since college (and then only a brief overview from a Protestant perspective), so I’m mentioning this by way only of generalities.

While it seems quite evident that Calvin, Luther and the other reformers were not trying to become nominalist, is it perhaps fair to say that their theology leads in that direction anyway? Parish communities that call themselves Magisterial Reformed and actually adhere to the Reformation’s principles are, from my (limited) understanding, few and far between in the grand scheme of Protestantism.

Now I fully understand that just because many Protestants that say they have strong ties to the Reformation, yet are very nominalist in doctrine and praxis, does not necessary mean that Reformation doctrine and praxis must lead to nominalism.

I guess I’m basically asking is, in this case, does correlation imply causation? If so, is there good evidence for it?

If any of this was already referenced above, I’m sorry for wasting the time/space. I’m just thinking off the top of my head in response to Olaf’s comment above.

John

***While it seems quite evident that Calvin, Luther and the other reformers were not trying to become nominalist, is it perhaps fair to say that their theology leads in that direction anyway?***

We would have to point out evidence for or against such a claim (and since Luther spoke in bombastic terms 100% of the time, we would have to take anything he said with a grain of salt).

***I guess I’m basically asking is, in this case, does correlation imply causation? If so, is there good evidence for it***

Deductively, it never does. The cock crowing does not cause the sun to rise, even though the latter usually follows the former.

The only really strong argument that could imply the Protestants are nominalists has to do with imputation (which not all accepted, anyway). The standard canard is that imputation is a legal fiction, something which is true of the taxonomy but not true of reality. Hence, so some claim, nominalism.

However, such a movie ignores the validity of “speech-acts.” God speaks, and things happen. Real things. Not nomens applied to arbitrary events.

God speaks my vindication and it is so.

From an Orthodox perspective, God “speaks your vindication” (or any other of His decrees) not making it magically so (in a vacuum apart from what is actually transpiring in your own heart and person), but because your vindication, through Christ’s work within you, is objectively, subjectively and really progressively becoming reality, so long as you are genuinely by faith working out your salvation in Christ (and God knows whether you will persevere in this and knows your end).

” The standard canard is that imputation is a legal fiction, something which is true of the taxonomy but not true of reality. Hence, so some claim, nominalism.”

Why is that a canard? What, if any, criticisms of the Reformed faith would not be classified as “canards” per your understanding?

God justified the ungodly (Romans 4). Your gloss makes it look like God justified the godly.

Ah yes, but we all start out sinners, and transformation is a process–in vs. 5 the tense of this verb implies a process. So everyone who is “justified” through Christ, starts out ungodly. At least that’s how I understand that–not sure what official Orthodox exegesis by an expert in the languages (which I am not) would offer. Of course, Orthodox would understand this whole section of Scripture as having to do with Old and New Covenant (i.e., directed to the first-century Jewish understanding of their special election)–“works of the law” = demands of the OT Law, not “good works” as in the polemics of the Reformation. Good works (“faith working by love”) and a true and living faith are two sides of the same coin. You don’t have one without the other. I’m guessing the New Perspective on Paul would be more compatible with Orthodox understanding of these passages, but I’m not an expert on either.

What you call justification I would call sanctification. I have to allow for an “extra nos.” The NPP would be compatible only to an extent.

That’s understandable given Reformed and Protestant parsing of this issue. For Orthodox, salvation is of a piece, and the different aspects of it addressed in Scripture are perhaps analogous to views of the same “thing” from different angles–i.e., justification, sanctification and glorification are all looking at aspects of the same “thing”–and the whole thing, in terms of our personal appropriation of it in this life, is a dynamic process (whether justification, sanctification, or glorification). For example, Protestants are accustomed to associating our “glorification” with the end of that process–or the consummation of the process (and that is also true), but the Apostle Paul mentions our transformation as being “from glory to glory” in 2 Cor. 3:18. This holistic process initiated and empowered by God is also reflected, among other places, in the language of Romans 8:30.

There’s a discussion of justification and its place (or lack thereof) in Orthodox teaching here that might be of interest:

http://afkimel.wordpress.com/2013/05/31/eastern-orthodoxy-and-the-apostle-paul-where-is-justification-by-faith/

Fr. Alvin has a whole series on this topic (of which this post is just one).

One other thing I would like to say is that justification is not the same thing as salvation on a Reformed gloss. A lot of people outside the Reformed world like to make that assumption. I Have no problem in saying there is a process in salvation; provided that justification retains its extra nos, announcement-like status.

So, “extra nos” = announcement (outside of “salvation” proper)? I’m not familiar with the terminology. If you’d like to elaborate briefly, I’d be interested.

Extra nos means “outside of us.” Justification on the Reformed gloss is, among other things, God’s announcement that we the ungodly are declared just.

The Reformed believe in union with Christ, sanctification, and struggle. We just don’t make it the grounds of our justification.

Thank you, Jacob.

Found this, which may be of interest (for another view):

http://orthodoxruminations.wordpress.com/2013/08/04/paul-and-justification-an-orthodox-perspective-on-the-new-perspective-on-paul/

I’m familiar with the NPP line. I was hard-line NT wright fan for three years. The claim that “Works of Torah” = “Jewish ethnic boundaries” is simply false. When Paul glosses “Works of Nomos” in Galatians 3, he is referencing Deuteronomy 28-29. The curses in Dt. 29 include both ethnic boundary markers and moral law violations.

Further, if you actually read EP Sander’s quotations of 2nd Temple Jewish rabbis, they are actually affirming the same type of semi-Pelagian merit theology that Luther attributed to Rome! This makes the Pauline reading, such that it is, very similar to the Lutheran reading.

Finally, if “Works of nomos” = merely Jewish ethnic markers, then it’s hard to see why Paul’s teaching of justification would be charged as antinomian.

Romans 3:28 “Therefore we conclude that a man is justified by faith apart from the deeds of the law.”

Jacob, I am not qualified to comment on EP Sanders nor on the data you present. It would be uncontroversial, though, I think to acknowledge that in the context of Romans 4, Paul is condemning the externalism of the Jews of his day (of which their racism is a part), and not here addressing the works of faith. I think it is also uncontroversial from an Orthodox or Reformed perspective to acknowledge that God declares “justified” the one who has faith in Jesus. But here is the point I would want to make from an Orthodox perspective, the one who has put faith in Jesus has been genuinely and ontologically “put right” with God in a very fundamental way, and so God is not declaring a righteousness/justification that does not relate in a real way to the actual spiritual state of that person, regardless of habits of sin (ungodliness) that have yet to be overcome. God “justifies the ungodly” in the sense that we have all sinned and fallen short of the glory of God, even those who turn to Christ in faith.

I certainly agree that Paul is condemning Jewish externalism, among other things. My point is that when Paul uses the phrase “works of the law,” and references Deut. 28-29 in Galatians 3, he is referencing a law code that includes both moral laws and ceremonial laws. This is where the NPP falls flat.

And I say that as someone who generally likes Tom Wright (he autographed a book for me).

I can even accept the ontology part, but along different lines. God can declare us not guilty because Christ is our covenant head.

As to works of faith–as long as one doesn’t make that the grounds of justification, I’m not too bothered by it. If we do make anything we *do* the grounds of our acceptance with God, then God really can’t be said to justify the ungodly, contra Romans 4

Orthodox do not teach that our works “justify” us in any other sense than is taught in the book of James 2:21, 24-25. We agree with Protestants that we cannot earn or merit God’s grace and cannot obligate Him by our good works. This is because, among other things, His love for all is unconditional, as was the father’s for his two sons in Christ’s parable of the prodigal son. If it is freely given, then by definition it cannot be earned (though it can be spurned).

Further, as we know the Scriptures teach that in order to be be righteous (thus declared righteous) by keeping the Law of Moses, one is obligated to keep the whole Law perfectly (in letter and Spirit), which no man, save Christ, has done.

Where the issue is externalism, I don’t think Orthodox would make a distinction between the moral vs. ceremonial law. Both kinds of laws can be observed only outwardly, disregarding their real meaning and spirit (and thus uselessly). We also agree (virtually) no one has never sinned and lived up to the moral law perfectly, so we certainly agree that no one will be justified on that account, even though we recognize that the moral law, found in both Old and New Testaments, remains binding on the believer in a way the OT ceremonial law does not.

I don’t find the phrases “covenant head” nor “not guilty” in the pages of the Scriptures, much less together as you have placed them. Are there verses or passages in the Scriptures that you take to mean what you state here? Perhaps that would be a place to start for discussion.

What it means for an Orthodox that Christ is the Head of His Body the Church is understood in much more relational and organic (ontological) terms. Consider the biblical analogies of Husband and Bride and of Vine and branches. In Orthodoxy, both marriage covenant (not sure this understanding of covenant is retained today in the West–see this post: https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/glory2godforallthings/2013/07/26/no-wedding-vows/) and Vine and branches speak of a shared life (actual participation). What this means for an Orthodox is that there is a real union in which the life that animates the Head also animates the Body, such that the Body can become fruitful. The life of the faithful Orthodox Christian is one of continual confession of sin and renewal of one’s union with Christ in the Eucharist. It is an ongoing ontological reality maintained by faith and participation in the sacramental life of the Church. If Christ is my Head, I am not just declared “not guilty” from past sins (though that is true also), I am also presently being united with His life indicating an ontological change and being progressively by that same life cleansed from those sins and regenerated in the likeness of Christ.

The grounds of our justification is certainly the work of Christ on our behalf, but this is an actual foundation, not merely a legal prerequisite. Our works of faith are the means by which we personally each take hold of Christ, Who has first reached out to us through the Incarnation and in His institution of His Church.

***Orthodox do not teach that our works “justify” us in any other sense than is taught in the book of James 2:21, 24-25. ***

And is James seeing works in the instrumental sense, material sense, or teleological sense ? I maintain the latter, if you do as well, great. You are a Protestant.

***Where the issue is externalism, I don’t think Orthodox would make a distinction between the moral vs. ceremonial law.***

This distinction was long a part of theological vocabulary before Protetantism. The problem, if one denies it, is that you have a hard time saying eating shellfish is okay now but adultery is still bad, if both fall under the aegeis of the “The Law.”

***I don’t find the phrases “covenant head” nor “not guilty” in the pages of the Scriptures, much less together as you have placed them. ***

I was browsing through the archives of this site yesterday, and I ran across where Robert praised the idea of “suzeiranty treaty.” I am advocating th esame thing. “Covenant head” is short-hand for Second Adam (Romans 5)

***Are there verses or passages in the Scriptures that you take to mean what you state here? Perhaps that would be a place to start for discussion.***

Yes, but I’ll wait. I think Robert is about to do a major post on an upcoming topic, so I don’t want to distract anything.

***What it means for an Orthodox that Christ is the Head of His Body the Church is understood in much more relational and organic (ontological) terms.***

Why are these kind of metaphors from Scripture acceptable but Scripture’s own use of forensic language (Isaiah 53) merely metaphors? I have no problem with them. I dispute there is a 1:1 identity between the 2nd hypostasis of the Trinity and the Church, if that’s what you mean by body of Christ.

***The grounds of our justification is certainly the work of Christ on our behalf, but this is an actual foundation, not merely a legal prerequisite.***

I don’t see a material difference. Why is “legal” such a bad thing?

Legal is not bad–it is just inadequate (especially as understood in much of modern Protestantism). If it being understood in the full OT sense (which I sense is not the case, such as with Reformed PSA theory), even there it has limitations in that, according to the NT, it cannot fully explain nor accomplish the whole economy of our salvation revealed in Christ, which is by the Holy Spirit and which requires Christ’s Resurrection as much as it does His Death on our behalf.

“suzeiranty treaty”

Perhaps Robert can explain then how this fits in with the Scripture’s teaching. I am familiar with the Scripture’s teaching on the Second Adam, but your language invokes again the ideas of mere legal acquittal and some sort of legal contractual obligation that stops short, it seems to me, of a depth of understanding of what is really being referenced in the Scripture’s teaching in this area, given the Scriptural analogies for what it means that Christ is our head, that go beyond the fact that Christ succeeded where the first Adam failed.

“is James seeing works in the instrumental sense, material sense, or teleological sense ?”

I’m a bit suspicious that these various senses can only be artificially distinguished from one another, but that is just an intuition. Perhaps you could elaborate on what you see as the difference, but I suspect an Orthodox paradigm is just so removed from your thinking, some of our mutual questions will just be talking past one another.

Thanks for the conversation, Jacob. It’s clear I’m not well versed enough in all the ins and outs of the various Reformed schemes of interpretation on such things to interface with you. Perhaps Robert will be able to address some of the questions you’ve raised in a way that will be helpful to both of us in some of his future posts

***it is just inadequate***

I disagree.

***but your language invokes again the ideas of mere legal acquittal and some sort of legal contractual obligation that stops short***

Even if that were true, I wouldn’t be bothered by it. Christ as my covenant head (Romans 5:21; Isaiah 53–very clearly says he represents his people and took their sins)—the point is not mere legal representation, though such could be included.

***I’m a bit suspicious that these various senses can only be artificially distinguished from one another, but that is just an intuition.***

It’s simply Aristotle’s distinctions on causality. And before someone says that is Greek thinking, I would remind him or her of “Hypostasis,” “ousia,” “hyper-ousia (!!!!!)”, “kinesis-motion,” and so on. If Greek thinking is fine to elucidate the mysteries of the Trinity, then it is equally legitimate to explain passages in Scripture.

***but I suspect an Orthodox paradigm is just so removed from your thinking***

That may be so, but my criterion of judgment is not whether a teaching lines up with the Orthodox phronesis, but whether it is true or not.

***Thanks for the conversation, Jacob. It’s clear I’m not well versed enough in all the ins and outs of the various Reformed schemes of interpretation on such things to interface with you. ***

Thanks to you, as well.