A Response to Protestant Criticisms

Today’s posting is by Eric Jobe. Eric has graciously given permission for his article which originally appeared on Orthodoxy and Heterodoxy to be reposted here. Source

As Protestant Christians find their way to examining the Orthodox Christian faith, they very often remark about the inconsistency of Orthodox Christianity on the matter of justification by faith, or else they even say that Orthodoxy has no such doctrine of justification. Indeed, the term justification may be a bit curious to most Orthodox Christians who were not reared in Protestant homes, for one seldom encounters the term in Orthodox liturgy or theological discussion. It is perhaps most often encountered at the liturgical reading of the epistles of St. Paul or St. James, or perhaps one might recognize it from the service of baptism or chrismation. Yet these occurrences may pass notice and thus understanding.

But what of this notion of justification, and why should we pay heed to such criticisms made by Protestant observers of our Orthodox faith? A simple answer to this question might be that justification is a biblical doctrine, and it is one that has had a very significant impact in the history of Christianity. Nevertheless, the term justification has largely disappeared from Orthodox theological vocabulary, and this I would argue is for good reason.

A Changing Consensus

Critical scholarship over the last 50 years or so has begun to reassess the issue of justification in the epistles of St. Paul in conjunction with our ever-growing understanding of 1st century Judaism and its own understanding of what we could describe as “justification.” In the various sectarian theologies of Second Temple Judaism leading up to the time of Christ and the Apostles, Jews were very much concerned with who was in and who was out, i.e., who were the righteous before God and who were the wicked objects of His wrath. In order to maintain a position of being righteous before God, a pious Jew was expected to live in complete fidelity to Torah, the Law of Moses. The only question was, by whose interpretation of Torah should one live? The Jewish sect responsible for writing many of the Dead Sea Scrolls believed that they alone had received the correct interpretation of Torah, given to them by a man they called the Teacher of Righteousness, and all others were under the sway of the Wicked Priest or Man of the Lie, who had led them astray.

As the Gospel of Jesus Christ reached various Jewish communities throughout the Roman world, the question naturally rose as to what they should do about the Torah. Having believed in Messiah Jesus, should they still keep Torah? Furthermore, what should they do about Gentiles who came to believe in Messiah Jesus – should they become circumcised and follow Torah?

Paul and James, Two Valid Perspectives

St. Paul’s answer to this question was decisive as well as ingenious, for he categorically denied that Jews or Gentiles were obligated to keep Torah, for they had been justified by faith apart from the works of Torah, such as circumcision and kosher dietary regulations. Furthermore, all had been baptized into one body, the Body of Jesus the Messiah, and had been given the gift of the Holy Spirit who would enable them to do what the Torah could not – to keep the righteous requirement of the Torah and live in obedience to God. To be baptized into the Messiah was to be baptized into His death and thus die to Torah to which they had previously been bound and to live unto Messiah Jesus by faith and the power of the Spirit.

St. James, on the other hand, likely felt that Paul had gone a bit too far in his jettisoning of the Torah, for he maintained that the Torah was still useful for instructing in righteousness, and that the works of Torah were to be understood simply as putting one’s faith into action. While Paul focused upon Torah as the means by which the Jews sought to establish their own imperfect righteousness before God, James saw the Torah as an efficient means by which one might live in obedience to God through faith. In spite of an apparent disagreement (which it was not in actuality, but only a difference in the use of terminology), it seems quite clear from both Paul and James that they agreed that both faith and obedience to God were necessary components of salvation, though they went about describing it in different ways.

The importance of all of this is to emphasize that justification is foremost an issue regarding the place of the Jewish Torah in the life of early Christian communities. For this reason, it is perhaps rightly de-emphasized in Orthodoxy, for we no longer have to deal with the same issues that the new Christian communities, composed of Jews and Gentiles seated at the same table, had to deal with.

Justification and Salvation

Justification is only one aspect of our salvation in Christ, which is manifold and comprehensive. Various aspects of this salvation have been emphasized in different eras or different geographic regions (i.e., East and West), but none can be exclusively claimed as the sole understanding of salvation. Let’s look at a few of these terms and ideas in order that we may parse out their connection and how they comprise a more comprehensive look at our salvation:

Justification – This term deals with how a person comes into and maintains a right relationship with God. Ultimately, this is made possible by the cross of Christ, by which He made expiation for our sins, granting us forgiveness and bringing us into a right relationship with God. Justification is accomplished at baptism and maintained through a life of obedience to God and confession of sins.

Sanctification – Sanctification is the process of separating a person or thing for exclusive use by God or for God. Holiness, the result of sanctification, is the state of being exclusively devoted to God. This ultimately requires purification from sin and detachment from the world and material things. This is usually seen as an ongoing process that one undergoes throughout one’s life. Sanctification is accomplished through ascetic struggle.

Glorification – The final state of Christians perfected in Christ after His Second Coming. While this term (as a participle) was used in Romans 8:29, Orthodoxy normally understands this idea to be the culmination of theosis (see below).

Adoption – The result of being engrafted into the Body of Christ through Baptism. We are adopted by God the Father as sons and co-heirs with Jesus Christ (Romans 8:15-17). Adoption is the state by which we may partake of the divine nature (2 Peter 1:4) through theosis (c.f. the series on theosis and adoption by Fr. Matthew Baker).

Faith – This term can be understood biblically in two senses: (Paul) trust, fidelity, or loyalty to Christ that includes obedience and good works, or (James) simple cognitive belief (James 2:19) that must be complemented with good works.

Works – Also, this term is used biblically in two senses: (Paul) the “works of the Torah” such as circumcision, kosher regulations, and the myriad of other ordinances of the Law of Moses that are incapable of establishing one as righteous before God, or (James) good works (in an ethical sense) and obedience before God which accompany genuine faith.

Theosis/Deification – Both the result of being adopted as sons and daughters of God through baptism into Christ and the process of attaining to the fulness of the divine nature and conformity to the image of Christ. The concept of theosis has the potential to be wildly misunderstood when it is taken away from its moorings in the concept of adoption and the sacramental life of the Church. If it is understood in a “mystical” or gnostic way as a spiritualized state of elite initiates or recipients of some special grace withheld from other baptized members of Christ’s Church, then we err from Patristic teaching on the matter.

Christus Victor – Literally “Christ the Victor” (IC XC NIKA), this concept is perhaps the most common expression of our salvation in Orthodox Christianity. It is most aptly characterized by the Paschal apolytikion: “Christ is risen from the dead trampling down death by death and upon those in the tombs bestowing life.” We are saved, because Christ has destroyed sin and death by His own death, and given life to us by His resurrection.

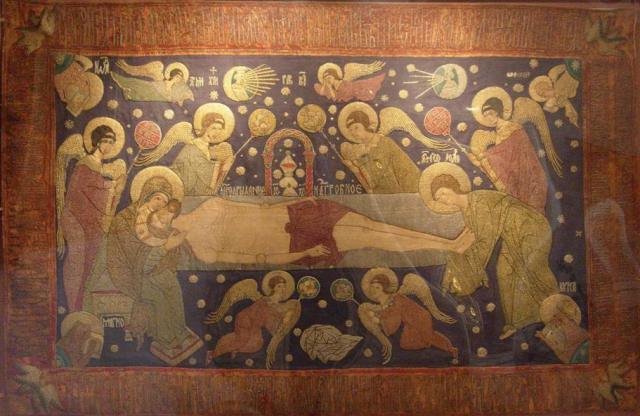

Tapestry of our Savior — Embroidered altar cloth – Yaroslav 16th century source

What to Take Away

• All of the above concepts are woven together to form the complete tapestry that is our salvation in Christ, and none of them alone can be exclusively made to be real essence of salvation to the virtual exclusion of the others.

• Justification is an important aspect of our salvation in Christ, though it is perhaps overemphasized in certain corners of Christianity. Justification is something that is inherently experienced and lived by every baptized Orthodox Christian, though it may be taken for granted.

• We should not allow early Christian disputes about the Law of Moses to cause us to stumble by creating false dichotomies between faith and works that do not take into account the various nuances given to these terms by biblical writers.

• Justification is wrongly set up as a singular touchstone of right doctrine, because it is only a part, not the whole of our salvation in Christ. As such, it cannot be considered the definitive aspect of soteriology (the doctrine of salvation) to the exclusion of other aspects of it.

• Justification is accomplished at baptism, the point where a person is granted forgiveness of sins and placed in a right relationship with God, and it is maintained through a life of obedience to God and confession of sins.

Justification accomplished at baptism source

As such, Orthodoxy does have a doctrine of justification, though it may not be explicitly referred to as such or emphasized as much as it is in certain Protestant communions. Orthodox Christians can confidently state that Orthodoxy does properly regard the biblical teaching of justification as being by faith apart from the works of the Torah, though faith is rightly understood as a life lived in faithful obedience to God. It is accomplished at baptism, the sacramental instrument by which sins are forgiven, and is maintained by confession of sins. Justification is integral to the life of every Orthodox Christian, and while we may not use the term quite so prominently as Protestant Christians, we nevertheless take it very seriously.

Eric Jobe is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at the University of Chicago. He specializes in Hebrew poetry, the Dead Sea Scrolls, and Second Temple Judaism. He is an instructor of Bible and biblical languages for the Orthodox Church in America, Diocese of the Midwest, Diaconal Vocations Program.

Very good summary, well said. When looking at this as an inquirer it

did not immediately hit me that “salvation” could be seen and under-

stood from a variety of perspectives…or analogies. It is a pity that some

protestants reduce salvation down to a narrow minimalism. Bishop NT

Wright has written on this a good bit and some Presbyterian groups

have picked up the fact that the NT authors and Apostles lived and breathed

— and thus tilted their focus upon Second Temple Judiaism — not Roman

Catholicism. That Salvation is broader that just one from of legal justification,

and is impoverished if left only as that can be arresting. Sadly, few protestants

openly say they got most of these “new perspective” from ancient Orthodoxy.

The Reformers conceived of justification using the language of the courtroom.

For there is no difference; 23 for all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God, 24 being justified freely by His grace through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, 25 whom God set forth as a propitiation by His blood…

A possible translation for “justified” (δικαιοσυνη) is a courtroom verdict absolving of guilt, but ordinarily it is thought of as “made righteous,” the consensus of interpretation of the Early Fathers. The innovation of the Reformers was the idea forensic justification and penal substitution, by which Christ’s sacrifice on our behalf satisfied the wrath of God in this theological courtroom setting, an idea that more or less influenced most later Protestant thought, even for non-Calvinists. God required the death of his son on our behalf in order to satisfy the demands of his wrath, according to this view.

This Reformed view was informed by the Western Church’s understanding of original sin, that is, that all are condemned due to the sin of Adam; the sentence of death being removed by faith in Christ through penal substitution and forensic justification, verdict of “not guilty.”

Reformed theology is very systematic and precise, it has a legal feeling to it. To my knowledge the Orthodox, not accepting the scholastic tradition of the West, do not really have a work of systematic theology to compare with Summa Theologica or the Institutes,, for instance. But the Fathers’ understanding of theosis and sin seems to me to be more human and more practical without a lot of complicated theology.

The Calvinist-Baptist blog “Pulpit & Pen”, which is affiliated with the “Founders Ministries” (a group trying to take over the Southern Baptist Convention and institute 5-point Calvinism as its official teaching), just put up an incredibly tasteless blog post stating that the martyrs who are being killed in the Middle East right now are not “real” Christians because they don’t believe in JBFA.

And as a Reformed person, I am deeply ashamed at what Founders has done. I wonder how many people can honestly tell the difference between miaphysitism and monophysitism?

Jacob,

I’ve heard a Coptic Orthodox priest explain to me why he is a miaphysite, not a monophysite. I’m still trying to make sense of it. But having said that I do recognize that he and the Coptic Church believe in Jesus Christ.

Robert

And they are offended with the slightest hint they are historic

schismatics separated from the ancient Faith handed down by

the Apostles. Lord have mercy.

I’d be interested in finding out more on “theosis.” Can someone point me to a book or essay? RC here, but just look the EO Church. Been to a few Byzantine Rite Catholic masses over the past year and am enthralled. I also hear the Byzantine Rite Catholics have been in dialog with the Eastern Orthodox church concerning possible future discussions on having a closer relationship with the Roman Church. I don’t want to say the word Unification.

In Christ,

Ron

Welcome to the OrthodoxBridge!

For starters you might want to read the article on the Antiochian Orthodox Archdiocese website and the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese website.

I encourage you to keep reading Scripture and learn from the early Church Fathers. This will help bring Christians today closer to the early Church and to each other as well.

Robert

Thank you for a thought-provoking article. Even as a Reformed, non-Orthodox Christian, I can identify with a lot of it and was nodding along for most of the article. There are terminology and emphasis differences, but that can be a good thing (to see the same thing from a different perspective).

The one question I had, is that the Orthodox doctrine of justification is that “[i]t is accomplished at baptism, the sacramental instrument by which sins are forgiven, and is maintained by confession of sins.” I’m wondering if this is purely a traditional stance, or if there is Biblical “justification” (sorry, couldn’t resist) for it? Every instance I’m aware of in the Bible of the word (and most of the concept) of justification is connected with faith rather than a specific sacrament … my biases are obvious, but I’m also obviously going to be looking for scriptural justification rather than just changing them based on your word :).

As far as justification being overemphasized or set up to be a singular touchstone – in my experience, that’s mostly when talking (like this) to people with a different understanding of justification. We tend to agree far more on the other aspects of salvation, so why not start with the one we disagree most on? In actual Reformed church life, justification is merely one aspect of salvation – an important one, given that without it, none of the rest really matter (although that could be said for all of them), but certainly not the only one or the main one to be concerned about – in fact, you could say the opposite, as in Reformed theology, one really has little to do with one’s own justification, so if you’re looking for where to spend your energy, the focus is on sanctification, or, to put it differently, how to respond to being justified.

It also seems to me that there’s a bit of a terminology gap here, as I read the definitions of “adoption/theosis” and think, I know those concepts, the author’s talking about “justification/sanctification”! Not that the definitions for those words are wrong, either, it just seems that the distinction is kind of artificial. Eg, you have as justification entering into a right relationship with God and as adoption how we get into “the state by which we may partake of the divine nature” – to me, that’s repeating yourself. Sanctification is presented as “purification from sin and detachment from the world and material things” and theosis is “the process of attaining to the fulness of the divine nature and conformity to the image of Christ” – again, so similar as to be (to me) the same thing.

Again, thanks for the thought-provoking article, just wanted to present a (hopefully clear) example of a Reformed view of the same concepts (which isn’t so different from the Orthodox view, albeit packaged differently and with a very different view of the sacraments).

Rob W,

I’m glad you enjoyed Eric Jobe’s article. I’m sure he will have something to say in response to your comment.

The teaching that one’s sins are forgiven in the sacrament of baptism can be found in Acts 2:28 when Peter proclaimed: “Repent and be baptized, everyone of you, in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins.” It can also be found in Titus 3:5-6: “He saved us through the washing of rebirth and renewal by the Holy Spirit, whom he poured out on us generously through Jesus Christ our Savior, so that, having been justified by his grace, we might become heirs having the hope of eternal life.” And then there is Acts 22:16 when Paul recalls his own baptism and the instruction Ananias gave him: “Get up, be baptized and wash your sins away, calling on his name.”

You’re right that we are justified by faith but the question that needs to be asked is: What do we mean by ‘faith’? Is faith only intellectual assent? Or is it embodied through bodily actions? The integration of the two can be found in Romans 10:10: “For it is with your heart that you believe and are justified, and it is with your mouth that you confess and are saved.” Taken in isolation this verse can be read in the ways many Evangelicals would, i.e., as a private interior affair, but in the broader context Romans 10:10 can be understood as alluding to the confession of faith on makes in baptism.

The Reformed tradition affirms the close relationship between baptism and justification (Westminster Confessions XXX.1). They refer to sacraments as “holy signs and seals of the covenant of grace.” (Westminster Confession XXIX.1) Orthodoxy sees a much tighter connection between the sacrament of baptism and our salvation in Christ. It reaches that we are born again through baptism. I found the Reformed tradition’s teaching on covenant very helpful for understanding how baptism brings about salvation. If justification consists of being in a right relationship (being righteous) and if a right relationship (being righteous) consists of being in a covenant relationship, then entering into a covenant relationship with Christ as Lord will result in one’s justification (being made righteous). Please see my article “‘Born Again’ Experience or Baptismal Regeneration” which can be found in Orthodoxy and Heterodoxy.

I’m glad you see the similarities between the Reformed tradition and Orthodoxy when it comes to sanctification and theosis. In this blog site I try to present both the similarities and differences between the Reformed and Orthodox traditions. You might be interested in reading Robert Letham’s “Through Western Eyes: Eastern Orthodoxy: A Reformed Perspective.”

Robert

Thank you for the further links, I’ll definitely read them! As I read your response (and other articles on this blog), I do see similarities between Reformed and Orthodox theology. I’m not really surprised – even if the emphases are different, the underlying objects are definitely still recognizable.

Thank you, too, for the texts on baptism/justification. As you’ll probably acknowledge, they don’t necessarily read that the moment of the physical act of baptism corresponds to the moment that the sins are forgiven, which to me opens up the door that the Orthodox understanding is indeed mistaking the sign for the thing signified. I definitely agree that there is a close connection even in the Reformed tradition, just the “causality” (not exactly causality, but close) runs the other way. So I’m not changing my mind on it just yet – there are also many justification-type texts that do not mention baptism, which to me makes more sense from a Reformed understanding.

As for what I mean by faith, it’s definitely not just a private interior affair or an intellectual assent. Hebrews 11 has the best definition I’m aware of, but overall the Bible is clear that a true faith necessarily (always) involves outward actions and deeds as well.

Again, thank you for the response, it’s not always so nice to correspond with someone from another faith tradition on the internet!

Rob W,

I’m glad that you believe that faith is more than a private interior affair and that true faith involves outward action. I understand you mean that if one has come to a personal faith in Christ as Lord and Savior that this will lead to baptism. One of the challenges I faced when I was a Protestant was the belief among some Evangelicals that making a decision for Christ was all that was needed to be saved and that water baptism was optional but not necessary.

As far as baptism as the moment of justification I see it as both a moment and a process much like the “I do” said by the couple in the wedding ceremony. It’s crucial but it’s not all there is to the wedding. In the larger context the wedding is but the beginning of a lifelong commitment. It calls for our commitment and God’s grace to make it work.

It doesn’t bother me that you’re not in agreement with everything I wrote in my responses. While there is much that Orthodoxy and the Reformed traditions have in common, there are also significant differences. It takes time to change one’s views. In my journey to Orthodoxy I changed my mind on certain things while retaining a lot of the good things I learned as a Protestant Evangelical. There is much we can learn from each other. In the mean time I hope we can build each other up through civil and charitable dialogue.

Robert

RonW, perhaps it would be easier to understand baptism not as a sign but as a means to and end. God usually uses means to accomplish His will. Jesus used mud and spit to heal blindness. No one would argue that it was some properties w/in the mud that healed the man but Christ’s power working through the mud. Likewise w/ baptism. We see pictures of it in the OT. Waters of the Flood washing away sin, the Israelites leaving Egypt via the crossing of the Red Sea, Naaman needing to wash 7 times in the Jordan or there would have been no healing. God is doing the work and it is through BOTH our faith, obedience and the water. In the NT, in addition to the vs. quoted by Robert, you have Jesus saying one must be born of water and Spirit. God is always there but working through water/baptism. In vs. 10 Jesus indicates that Nicodemus ought to have known these things. Peter also connects the Flood w/ its antitype…baptism “which now saves us” which is alongside the Resurrection. It’s part of the package deal. This was never disputed in the early Church. W/ their almost paranoid fear of corruption of the Faith it would seem strange indeed if this view of baptism was in error and yet there was no outcry on the part of the Church. Other passages that do not mention baptism are simply dealing w/ a different facet of our salvation that needed to be dealt w/. One shouldn’t haul those out of their context and hold them up as the be all end all of salvation. Our salvation is “multi-faceted”. The thief on the cross does not prove baptism is not necessary just that God is merciful. He had neither ability nor opportunity. That is not the situation w/ most folk.

Just to add to the multifaceted aspect of this question perhaps, I have read that the funeral services of the Church do not make a distinction between that for a catechumen being instructed in the faith in preparation for baptism and the baptized member of the Church: it is the same for both, and this service expresses the hope of salvation through Christ for the faithful departed. Perhaps this practice is in part where the Roman Catholic Church comes up with their recognition of the “baptism of desire” alongside water baptism and “baptism of blood” (martyrdom) as means by which some enter the Church. Alternate forms of “baptism” presuppose water baptism to be normative and the others to substitute only in the event of the lack of opportunity for water baptism.

As a very serious protestant Reformed disciple I must admit to a form

heretofore of theological fragmentation & segregation. Though it might

not be what Calvin & others intended, I believe the predisposition is en-

demic to protestantism. ‘Justification’ can be and often is analysed by

itself and easily becomes The narrow focus of salvation for many. I am

no expert (studying only 3+yrs before Chrismation Holy Saturday last

year) but it seems Orthodoxy is far more inclined to integrate all aspects

of Salvation. Justification, regeneration, sanctification, sacramental baptism, receiving the Holy Mysteries…all get mixed together in a complex whole.

That sacramental praxis…ie my Baptism, Eucharist, Confession all relates

to my justification and salvation is a novel idea for most protestants…but

not so in Orthodoxy. There is an attractive integration of the part(s) into a

beautiful wholeness in Orthodox that is absent in the far more fragmented

in Protestantism. Lord have mercy.

Hello, I am an evangelical Christian. Can anyone explain to me what paul means in Romans 3:31 that “On the contrary, we uphold the law”? If he’s referring to circumcision and Jewish dietary laws, does that mean that Paul is commanding us to be circumcised and follow Jewish dietary laws? I’ve always read that verse to be referring to the law as in the moral law (not as in circumcision). Because of that, I interpret Romans 3:28 as also referring to the moral law. Does he change what law he’s talking about without telling the reader he is? I know I’m about 9 years late to the conversation, but can someone help me out with that?

Dear Iron Man,

I have kept the OrthodoxBridge open to comment in case later readers have questions. The purpose of the blog is to assist people who have questions.

My understanding is that in Romans 3:31, Paul was referring to the Law of Moses. Paul spent a lot of time and energy refuting the Judaizers, Christians who believed that to be a Christian one also needed to follow the Law of Moses. The Jews believed that a right relationship with God was possible through keeping the Torah. This premise is flawed because it does not take into account our fallen human nature. Paul spends a lot time and energy in Romans 2 and 3 showing the failure of the Jews to keep the Law of Moses. The Law of Moses is good but fallen humanity is incapable of keeping the Law of Moses. In Romans 3:10-20, Paul ruthlessly grinds into dust any notion that observing the Torah will lead to salvation. The problem is not with the Torah but the people’s inability to keep it. They are fallen beings in need of new life in Christ So, the purpose of the Law of Moses is to prepare the way for the coming of the Messiah (Jesus Christ). Many had the mistaken impression that Jesus Christ came to bring an extension or a modification of the Old Covenant based on Mount Sinai. What they did not expect was that Jesus Christ came to institute a New Covenant that would supersede the Old Covenant. The Torah is good and all Jews should be proud of their ancestral history of being the people who received the divine revelation at Mount Sinai but they ought not impose this heritage on Non-Jews. Jesus Christ came to save both Jews and Non-Jews (see Romans 1:17). This means that Non-Jews can enter into a right relationship with God apart from the Law of Moses, that is, undergoing Christian baptism without circumcision.

You asked does Romans 3:31 mean that Paul is commanding us to be circumcised and keep kosher? I suggest that you read Romans 3 starting with verse 1. Pay attention to the flow of Paul’s argument. Romans 3:20 shows that the Law of Moses cannot save fallen humanity. What it does is make clearly evident our fallen nature. The Law is like a speed limit sign. It cannot help you be a good driver but it let’s you know that there is a speed limit and that there are consequences awaiting those who go over the speed limit. On this basis, one can affirm the Law of Moses while pointing out its inadequacies. One potential heresy in early Christianity was the jettisoning of the Old Testament. What Paul and the other early Christians sought to do was to affirm the Old Testament while not letting the Old Covenant circumscribe and confine the New Covenant. This is why Paul needed to write Romans 3:31.

One could ask could the word “law” be understood to refer to the moral law? The same argument Paul made against the Law of Moses applies to the moral law embedded in the human conscience. This alternative reading suggest the possibility that Non-Jews who are decent, caring people can be saved (in a right relationship with God). I once heard a story about a Christian who spent some time in Japan and was impressed by how kind and decent the Japanese people were. This precipitated a faith crisis in him. If the Japanese are such kind people, are they not already saved? Do they need to be saved? My response is that if salvation is personal union with the one true God and if union with God is only possible through union with Jesus Christ who was born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate, and rose on the third day, they are not saved. The goal of human existence is union with God, not being nice people. That is why the Christian Message is so radical. It presents Jesus Christ as the Way, the Truth, and the Life (John 14:6). Being circumcised is not enough. Keeping kosher is not enough. Being nice and kind is not enough. Faith in Jesus Christ is what saves us (Romans 3:22). Faith in Christ is not a matter of intellectual assent, it involves undergoing the sacrament of baptism which joins us to Christ’s death and resurrection (Romans 6:3-4). This is why Paul spends so much time to explaining the significance of baptism in Romans 6. Baptism is not a new legal requirment but a sacrament that unites us to Jesus Christ.

Robert