Part 4 of 4. Parts 1, 2, and 3.

In 1995, the New Geneva Study Bible was published by Thomas Nelson Publishers under the editorial leadership of R.C. Sproul and J.I. Packer.

R.C. Sproul has ambitious goals for this new study bible including using it to evangelize Russia.

He writes:

Beyond the borders of America, the New Geneva Study Bible may be used to expand the light of the Reformation to lands where the original Reformation never reached, especially to Russia and Eastern Europe. Source

What should be the attitude of an Orthodox believer in Russia towards the New Geneva Study Bible? I would say: cautious skepticism. Having been a Protestant Evangelical I can understand the enthusiastic Calvinist’s desire to share the Good News with everyone everywhere. However, as a convert to Orthodoxy I am quite conscious of the limitations of Reformed theology. In the spirit of caveat emptor (let the buyer beware), I list below some of my concerns about the New Geneva Study Bible and the original sixteenth century Geneva Bible.

The Bible and Interpretation

As discussed in an earlier blog posting theological tradition is the foundational bedrock upon which every study bible is rooted in and upon which it rests. The New Geneva Study Bible (like ALL Protestant study bibles) is thus not pure exegesis, but grows out of the Reformed tradition. This theological tradition is quite recent going back only to the 1500s. On the other hand the Orthodox Study Bible commentary rests on the teachings of the early church fathers. This interpretive tradition goes as far back as the second century and reflects a broad catholic tradition shared by Christians all across the Roman Empire and even beyond.

As discussed in an earlier blog posting theological tradition is the foundational bedrock upon which every study bible is rooted in and upon which it rests. The New Geneva Study Bible (like ALL Protestant study bibles) is thus not pure exegesis, but grows out of the Reformed tradition. This theological tradition is quite recent going back only to the 1500s. On the other hand the Orthodox Study Bible commentary rests on the teachings of the early church fathers. This interpretive tradition goes as far back as the second century and reflects a broad catholic tradition shared by Christians all across the Roman Empire and even beyond.

There’s a certain irony in the fact that BOTH the New Geneva Study Bible and the Orthodox Study Bible have in common the NKJV translation of the New Testament! If the differences cannot be attributed to differences in translation, then what is the reason for the differences in commentary? If one takes a step back one soon becomes aware that the commentary arise from a certain interpretive community. That is, we do not read the Bible alone but our understanding of the Bible is influenced by the community we are part of.

When one looks at the Reformed tradition one finds a theological tradition confined to parts of Europe. Furthermore, the Geneva Bible represents one specific, narrow stream of Protestantism. If one wants to study the theology of the early English Reformers, the sixteenth century variants of the Geneva Bible (not the updated version) is a good choice. But if one wants understand how Christians have historically understood the Bible from the early days to the present the Orthodox Study Bible is the better choice.

Passing Fad or Enduring Classic?

The Geneva Study Bible’s popularity was relatively short lived in comparison to the King James Version. Where the KJV appealed across the spectrum of Protestant denominations, the Geneva Bible appealed primarily to English Puritans. Thus, the Geneva Bible can be considered a passing fad or a transitional translation that prepared the way for the enduring classic of English literature, the King James Bible.

The recent attempt to bring back the Geneva Bible goes against the flow of history. It appeals principally to neo-Reformed Christians and is essentially a niche Bible. Its popularity will likely be short lived.

An Accurate Translation?

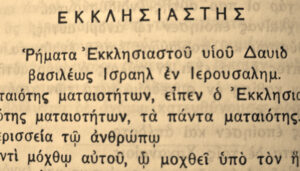

“The Greek World of the Old Testament” Source

A bible translation is only as good as its source text. The Geneva Bible like other Protestant bibles uses the Hebrew Masoretic text as the basis for its Old Testament translation. Historically, the shift to the Masoretic text is significant. Protestantism’s preference for the Hebrew text stems from Renaissance humanism’s ideal ad fontes—the belief that the path to true knowledge is through reading the classical texts in their original tongues. But this new humanist ideal marks a radical departure from the early church fathers’ desire to be discipled by the Apostles, not worldly wisdom. It was the Greek Old Testament (Septuagint) and the Greek New Testament that the Apostles and early Christians knew as their Bible.

Many of the Old Testament passages in the New Testament are either direct quotes or paraphrase from the Septuagint, not the Hebrew Masoretic text. Textual variations between the Hebrew and Greek Old Testament quotes are for the most part minor, but from time to time they will diverge; in that case which one should one prefer? I would suggest the older source text should be given preference. This makes sense in light of the fact that the Septuagint was produced about two to three centuries before the birth of Christ. The Masoretic text would not be compiled by Jewish scholars until the 600s to 900s. This makes the Greek Septuagint almost a thousand years older than the Hebrew Masoretic text!

A Conservative or Innovative Bible?

The Geneva Bible was one of the first bibles to tamper with the biblical canon by excluding the deuterocanonical books (aka Apocrypha). This is not a minor issue but centers on the question: Is this book or writing inspired by God? It takes a certain amount of audacity to claim to have the authority to make that determination!

In my first posting on the Geneva Bible I traced the gradual evolution of the Geneva Bible. The first printing in 1576 contained the biblical canon much like the Roman Catholic Church’s but by 1599 the Apocrypha was left out. This action stemmed from the increased hostility between Protestants and Roman Catholics. It can also be seen as stemming from the English Reformers’ intolerance of the in-between status of the deuterocanonical books which were considered inspired but not on the same level as other parts of the biblical canon. Gary Michuta in an insightful article showed how the exclusion of the Aprocrypha led to changes in the marginal notes that sought to show the New Testament reliance on the Apocrypha, e.g., Matthew 27:48 and Wisdom 2:18, and Hebrews 1:3 and Wisdom 7:36.

This tampering with the biblical canon demonstrates the Reformed tradition’s innovative character. This is a radical departure from the historic Bible, not a conservative return to the early Church as some would like to think.

The Need for a Protestant Study Bible

The attempt to bring back the Geneva Bible represents a step backwards for Protestants today. The Geneva Bible reflects English Protestantism in the late 1500s before the emergence of King James Version in 1611. Since then many more English translations have appeared each with their own strengths and weaknesses. It is hard to accept the claim made by some that the Geneva Bible is to be preferred over all other English translations.

What is needed instead is a Protestant Study Bible that reflects the rich diversity of Protestant readings of the Bible. Such a bible would help advance our understanding of Protestantism’s complex and even contradictory relations with Scripture. The Reformed tradition is one facet of Protestantism’s complex and often conflicted hermeneutical history. The Protestant Study Bible that I am suggesting here would be a useful resource for Protestant-Orthodox interfaith dialogue. We share the same Scripture but we are separated by differing readings of Scripture. These divergent readings arise from fundamentally different hermeneutical starting points. Where Orthodoxy assumes Apostolic Tradition as the normative interpretive framework for reading Scripture, the Protestantism insisted on sola scriptura which in time took on an increasingly nuanced and qualified forms resulting in often contradictory interpretations.

A Political Agenda?

The New Geneva Study Bible seems to have become intertwined with a certain political agenda. We find in the treatise “The Forgotten Translation” posted on genevabible.com linking the Geneva Bible to American democracy.

Thanks to the Institutes of the Christian Religion, his printed sermons, the Academy, his commentaries on nearly every book of the Bible (except the Song of Solomon and the Book of Revelation), and his pattern of Church and Civil government, Calvin shaped the thought and motivated the ideals of Protestantism in France, the Netherlands, Poland, Hungry, Scotland, and the English Puritans; many of whom settled in America. The great American historian George Bancroft stated, “He that will not honor the memory, and respect the influence of Calvin, knows but little of the origin of American liberty.” The famous German historian, Leopold von Ranke, wrote, “John Calvin was the virtual founder of America.” John Adams, the second president of the United States, wrote: “Let not Geneva be forgotten or despised. Religious liberty owes it most respect.”

As wonderful as some moderns might believe the American democracy may be, it must not be affixed to the Word of God. The Bible belongs to the Church catholic and not just to one particular polity. One has to wonder if the Neo-Reformed missionary project is intertwined with an attempt to civilize the world according to the “American Way.” Rather than respect Russia’s Orthodox Christian heritage, the New Geneva Bible (Reformation Study Bible) seems to be an attempt to replace it with American Protestantism.

Conclusion

To summarize, despite the admirable motives for attempting to bring back the Geneva Bible there are significant problems with this particular bible:

(1) Its commentary notes come out of a relatively recent theological tradition, the Protestant Reformation which originated in the 1500s;

(2) It was popular for a brief period of time until superseded by the King James Version;

(3) It used the Hebrew Masoretic text instead of the Septuagint;

(4) It changed the Old Testament canon by leaving out certain books that the Christian Church had long considered Scripture;

(5) Its recent come back seems to be connected to the neo-Reformed movement within Evangelicalism; and

(6) The recent endeavor to export it Russia rests on the assumption that Reformed theology is superior to Orthodox Christianity.

So what should an Orthodox Christian in Russia say if offered a copy of the Geneva Bible? I would suggest that even if offered a free copy of the Geneva Bible, one should reply: Thanks, but no thanks. They might even challenge Protestant zealots to consider how the Geneva Bible is in reality a radical departure from historic Christianity. That it might be just as much a political tract promoting modern democratic Americanism as it is a “new and improved” Protestant version of the Bible. They could also offer to sit down with their Protestant friend and compare the Geneva Bible with the Orthodox Study Bible.

Robert Arakaki

What utter arrogance. I suppose that a Calvinists who believes that they are one of the special ones who has been chosen by God for salvation out of the mass of doomed humanity is likely to suffer from spiritual pride. As an historian, I seriously question the idea that freedom came from Calvinism. Calvin established a theocracy in Geneva which punished severely anyone who challenged Calvin’s teachings. Puritan New England had no religious liberty. Anyone who did not adhere to strict Puritanism was thrown out of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, such as Roger Williams and Ann Hutchison. One had to be a member in good standing in the Puritan Church to vote in secular elections. America had to overcome Calvinism to develop freedom. Puritanism was the state Church in Mass. until about 1830. The immigration of people with different religions led to the concept of religious freedom in America. That and the vast frontier that made it impossible for the government to enforce religious conformity because someone who did not follow the teachings of the state Church, Puritanism in New England, and Anglicanism in the South, could always move to the next valley and be left alone by the government.

Fr. John W. Morris

It’s a bit misleading to say that the Masoretic text was compiled in the 600s to 900s and is therefore younger than the Septuagint. Many manuscripts from the dead sea scrolls are basically similar to the Masoretic text (over and against the Septuagint). The Masoretic text is surely a textual stream that seems to go back to pre-Christ times.

It’s not like the septuagint is monolithic either. There is a mish-mash of streams of transmission there too. There have been various recensions of that at various times in various centuries.

It’s just not factual to say that the Septuagint is in any sense 1000 years younger than the Masoretic text. The Septuagint, whose textual corruption is equally as bad, has at least as many textual problems, and probably more because of the corruption of a number of conflicting translations in various centuries. Both the type of text found in the Septuagint and the type of text found in the Masoretic text, as far as we know, both date from pre-Christian times. Which is closer to the original is not clear.

I mean, come on. Jerome used the Masoretic text as the basis for the Vulgate, and that was in the late 300s. Origen used it in his textual studies in the 200s. It wasn’t fabricated by some 7th century Jews.

Something that must be said in all this is that when the Masoretic text represents the original text (and surely it must be said that this is most of the time, if only because the Masoretic and Septuagint are roughly the same), clearly it is an awful lot older than the Greek translation.

It’s also misleading to say the apostles used the Septuagint, end of story. There are plenty of instances where the apostles seem to use the Hebrew text over and against the Septuagint.

I don’t see any problem using the Septuagint text. But it just seems a bit silly to have a one eyed view of it, without seeing the validity of the counter arguments.

One might point out that the NKJV is from a recension of the NT Greek text, neither conforming very well to the Byzantine tradition, neither conforming very well to the best textual scholarship. (Like for example, the infamous 1 John 5:7, which isn’t really found in any Greek manuscripts).

Why they chose the NKJV, without at least removing its more egregious errors, I find inexplicable. To go to all the trouble to rewrite the OT from the Septuagint, but not remove 1 John 5:7, which has absolutely no place in the Greek tradition, is odd to say the least.

John,

Welcome to the OrthodoxBridge!

I condensed the material pertaining to the Septuagint and the Masoretic text considerably because the focus of the blog posting is on the Geneva Bible. I would like to note that it would help if you took a more nuanced in your discussion. For example, it can be said that Jerome translated from a Hebrew text for the Old Testament, but it is not accurate to assert that he relied on the Masoretic text. Do you have evidence of that? The problem lies with your confusing the Masoretic text with the manuscript tradition for the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) which comprises a number of manuscripts including the Dead Sea Scrolls. I look forward to scholarly research comparing the Septuagint and the Masoretic Text against the Dead Sea Scrolls. There are glimpses of that here and there. The results have been intriguing. But the point I wanted to make in the blog posting was that the Protestant shift to the Masoretic text for the Old Testament translation was a historically significant shift. I’m sure you would agree with me on that.

Robert

Well Jerome’s Vulgate is pretty much the Masoretic text. Very close. I can quote references for that if you want, (Kenyon, Frederic G. (4th ed. 1939). Our Bible and the Ancient Manuscripts), but its kinda obvious too, if you look at the major variants.

It’s certainly not a Hebrew text like the Septuagint (which have been found in the DSS). I’m not confusing the Hebrew manuscript tradition with Jerome’s exemplar. The are indeed fragments of Hebrew found in DSS that seem to indicate that there was a Hebrew line of transmission like the Septuagint. But it seems to have been a less important stream, judging both the DSS, and the fact that Jerome and the Masoretes and other sources seem to have favoured the proto-Masoretic stream. I suggest the book by Karen H. Jobes and Moisés Silva if you want an introduction to the topic.

Anyway, there was really no shift whatsoever when the Protestants used the Hebrew. They basically took Jerome’s exemplar, which at that time was the west’s text, and retranslated it from the source. Which did actually make sense for them.

If you want to accuse someone of a big shift, accuse Jerome. But even there, he had predecessors in using the Hebrew, like Origen and others.

(I’m new to posting on Orthodox Bridge, but here goes…)

John,

You said, “It’s also misleading to say the apostles used the Septuagint, end of story. There are plenty of instances where the apostles seem to use the Hebrew text over and against the Septuagint.”

I have a document that lists every NT verse that contains direct quote of the OT along with the matching MT and LXX verses. At least 95% are verbatim quotes from the LXX. It is not far-fetched to conclude that the LXX was definitely the version of choice for Christ and the Apostles.

I also might mention that I recently watched a talk by NT Wright who argues that the Apostle Paul builds his whole argument in the book of Romans from the LXX version of Isaiah over against the MT.

Peace.

Barnabas,

Welcome to the OrthodoxBridge! Glad to have you join the conversation. Interesting point about NT Wright!

Robert

Well, there’s no doubt that for most people back then the Greek was a more convenient source to quote than the Hebrew. Even more so if you’re writing in Greek. And it may even have been that some of the apostles didn’t even know Hebrew.

I haven’t gone through the entire list myself, but others have. e.g. here: http://mysite.verizon.net/rgjones3/Septuagint/spexecsum.htm

where he makes the observation that “I noticed a tendency on the part of New Testament authors to deviate from the exact wording of the Septuagint, though they often kept the same sense”.

So I question your claim of “verbatim” in 95% of cases. If its not verbatim, then its hard to say with certainty they are quoting the Septuagint. The could be quoting the Hebrew with an off-hand translation. Or they maybe translating the Hebrew themselves but under the subconscious influence of the Septuagint.

If you want to have a lower standard of agreement, where it’s similar, then sure it would be 95%. But the agreement with the MT is probably 70% too. Clearly they liked the Septuagint. Doesn’t mean they didn’t like the MT though. If I went into a Russian Orthodox church in America, and found most people quoting the NKJV, does it mean they disdained the slavonic version?

And of course there are times when the NT agrees with the MT against the Septuagint too. Like 1 Cor 3.19/ Job 5.13 “He catches the wise in their craftiness” versus the Septuagint, “who takes the wise in their wisdom” for example.

So yes, the Septuagint was the favourite version in the early times. But does it mean it is somehow wrong to use the Hebrew version? How do we jump to that conclusion? Clearly there were apostles who, at least sometimes, preferred the Hebrew to the Septuagint.

In my opinion, where there is a clear difference in sense between the MT and the Septuagint, then either one could be the original reading. You would have to look at it case by case. But most times there is slight variation between them it is simply because the Septuagint is a bad translation. It’s not monolithic. Some parts are translated quite well. Other parts are pretty awful, and you can’t put it down to being older or something. It’s just not very good. I seem to remember that a couple of the books were so bad, that they actually got replaced with different versions in the centuries. I’d have to go look it up. But either way, it’s hard to argue it is some kind of inspired translation. Yes, it sometimes preserves the correct sense when the MT is corrupt. But it’s still a translation, with all the inherent problems of that.

John,

I appreciate the interesting link and look forward to reading the content more carefully.

To be clear, I was not trying to imply that the MT is all bad but that the LXX should be, in most cases, perhaps be given priority. The issues with OT translations are definitely many which is why I’m surprised that most evangelicals believe the doctrine of plenary inspiration is so important.

Well, why should it be given priority? Yes, the apostles used it a lot. But presumably Moses used the Hebrew version a lot. Even on the simplistic level, we don’t know what the corruption is in what we know today in 2013 as the Septuagint, compared to the corruption that existed in 50AD, compared to the version in 240BC (or whenever) it was translated. I’m rather curious what Septuagint they used for the Orthodox study bible. All the published versions I am aware of are based on some kind of version of the oldest manuscripts, Sinaiticus, Vaticanus etc, rather than what you would call the common Byzantine version as it would evolve. The reason is that in the west there was little interest in the Greek OT for a long time, and when interest did come, it was in the oldest manuscripts available.

But that raises the question, why base your OT on the oldest manuscripts like Sinaiticus and Vaticanus, and then base your NT on poor quality and later Byzantine manuscripts? If the later Byzantine tradition is so great, why not base your OT on it as well? I guess these questions of different manuscript streams are important, since the Orthodox bible went to so much trouble to avoid one (the MT) in favour of a different one.

Interestingly, at Job 5:13, the Orthodox bible follows the MT against the Septuagint, because of 1 Cor 3:19.

The LXX is given priority because of apostolic tradition and our belief in the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church.

This is why we hold the Byzantine Text and that textual tradition in higher regard, as well; it is what we have received, and it is what was actually read and used in our church services—not “throwaway” copies of unused manuscripts and fragments, but extant texts from Gospel lectionaries, as actually used in the Liturgy. As with all theology, the reception of both the canon and the text of Scripture is a matter of holy tradition, and our reception of such in humble deference to the Body of Christ and the guidance of the Holy Spirit.

Textual criticism is secondary to all of this. At the end of the day, we still read the longer ending to Mark, and our services still quote the Septuagint versions of the Psalms and Prophets.

It is a substantial error to equate the Hebrew of Jerome or Origen (or even the DSS) with the medieval Masoretic Text. There are substantial differences, as any serious, scholarly study into both the DSS and the Samaritan texts will show. We cannot forget the number of Greek biblical manuscripts discovered near Qumran, as well—which are even labeled as “LXX” for whatever cave/text they signify.

Despite the work of both Jerome and Origen, the texts of their day were lost to history. The irony of Luther and other reformers’ ad fontes approach to the scriptures was that they abandoned a text with greater antiquity and priority for one that was only a few hundred years old, and the work of revisionist Masoretes.

For more on this, see Timothy Michael Law’s When God Spoke Greek, recently published by Oxford University Press.

John, If you look at some of saint Jerome’s quotes from the Hebrew text he was using then you will notice that it doesn’t always line up to what you have in your Masoretic text.

That might not be entirely surprising, since textual transmission was really messy back then. I think the point being made was that Jerome sought the Hebrew when he could have simply relied on the LXX.

As a neo-reformed Protestant (didn’t even know I was classified as that) reading the Septuagint for the first time I was struck with how much more Christological it was. Our Protestant bibles use ‘ anointed one’ or similar instead of ‘the Christ’ in the Septuagint. Also I never really understood John’s calling Christ the Word until I saw its use in the Lxx. I can understand a first century jew’s concern over the abundance of passages like those and the need to selectively preserve a group of manuscripts (masoretic) that make those references to the Christ and the Word as ambiguous as possible so as not reinforce the Christians’ claim that Jesus of Nazareth was indeed that person. Sorry for the run on sentence.

Joshua,

Welcome! Glad to have you join the conversation. Thank you for your insights.

For me what has impacted me was getting to know the Book of Sirach which has passages that sounds a lot like the Sermon on the Mount. Reading it has made me aware of the continuity between the Jewish Old Testament and the Christian New Testament. The tendency of Protestant bibles to omit the deuterocanonical books (aka Apocrypha) gave me the impression of a sizable gap of 350 to 500 years between the two dispensations but with the Orthodox Study Bible I’m becoming aware of how God has moved sovereignly in history with no break.

Robert

***Our Protestant bibles use ‘ anointed one’ or similar instead of ‘the Christ’ in the Septuagint***

Besides probably a quibbling over semantics, using “anointed one” (or even better, ha meschiach) is a preferable reading. “Messiah” roots Jesus back in his Davidic narrative. The import of “Christ” wouldn’t have been relevant until well after the Christian era began.

As to the evidence of Jerome and the MT,

It’s fairly common knowledge that Augustine rebuked Jerome for not using the LXX.

As did Pope Damasus I and his Synod of Rome. Jerome and Origen were exceptions, not the norm, and Jerome was prodded in the right direction.

The textual degradation of the west (departing from the more ancient custom of following the LXX canon and text) has come in more recent centuries, following the original Douay Rheims—and this in violation of one of Rome’s key early synods, and one of the most influential Saints of the pre-schism west (Augustine).

Rather than picking LXX over Hebrew (or vice versa), Augustine proposes that both traditions are inspired, but greatest priority should be given to the LXX. This is the same advice he gives Jerome, and it was the opinion of antiquity at the time (and still in the East).

There’s no substantial difference between saying Christ, Messiah, or Anointed One. They all connect with the same reality.

“Our Protestant bibles use ‘ anointed one’ or similar instead of ‘the Christ’ in the Septuagint.”

Errm, the word Christ means anointed one. Of course the Septuagint uses the word Christ. There is no other word in Greek.

“I can understand a first century jew’s concern over the abundance of passages like those and the need to selectively preserve a group of manuscripts (masoretic) that make those references to the Christ and the Word as ambiguous as possible”.

Conspiracy theories aside, I don’t think there are many candidates for that conspiracy. The only one I can think of is Psalm 22:16.

The removal of the Wisdom of Solomon and the Wisdom of Sirach are examples of this, not to mention Judith and Tobit. All of the citations in Hebrews from the OT by St. Paul are rendered nonsensical if he follows the Masoretic Text. There are key texts that go missing in the MT, conspiracy theory or not (it really doesn’t matter).

Guys, guys, remember the PURPOSE of the blog was to comment on the possible purpose of the New Geneva being taken into Russia, where Orthodoxy is the majority, not a discourse on semantics, etc. which is what you’ve all turned it into.

Also, those commenting on the Septuagint vs. Masoretic need to be reminded that the writers of the Septuagint were all JEWISH Rabbi fluent in both Hebrew and Greek. Unless you’re fluent in both ancient Hebrew and Greek (were raised speaking both), don’t criticize what YOU call errors, since concepts in one language don’t necessarily translate into the same exact concepts in another. The ideas may be similar but wording will be different. This is a basic truth in cultural and linguistic anthropology. Try to focus on the blog’s primary topic. To do otherwise causes silly debate over off-topic subjects, in this case translations. The point isn’t really translation so much as the “evangelism” of a particular group of people. How will Russian Orthodox Christians react or should they? Why do Americans tend to think only their brand of Christianity is right and why is there so much antagonism toward Orthodoxy, as if Orthodox Christians aren’t saved? Answer those questions since that’s really what Robert was focusing on. The other stuff was just background info on the evolution of the original and “new” Geneva bibles, not the focus of his discussion.

Kiki,

You have a good point here. People, let’s get to the main issue: Should Calvinists export the Geneva Bible to Russia which has a Christian heritage over a thousand years old? And whose faith predates Calvin and Luther by more than five centuries?

Robert

I’ve wrestled with that question for five years. On one hand, saying to people, “No, you can’t enter the country and tell people about Jesus” sounds a lot like the people whom Jesus rebuked for not letting other enter the Kingdom of God.

Does Russia have a Christian heritage? Sure, but that is an entirely different proposition that the Russian people today are Christianized in any real sense of the word. Yes, Putin has done a good job. Yes, Alexy II and Kirill have done a good job. But the average Russian is probably in a different situation.

And for those who know me, they also know I was one of the most vocal supporters of Holy Russia against the New World Order and the Phanar Freemasons. And when it comes to war against the Bilderbergs, I am all for Putin. (I still have Orthodox guys ask me for my old articles on Putin and Russia)

And while Putin has done much good for Russia, and while the horrifically declining birth rate is better from the 1990s, if something doesn’t change Russia might not exist in thirty years (unless you believe the Third Rome Prophecies). Yes, yes, I know the “new statistics” saying the birth rate is improved, but a lot of that improvement is from Muslim immigrants from Central Asia, which really isn’t an improvement at all.

Of course, that doesn’t even factor in the explosive political situations between Russia and Ukraine.

I say that to say this: given all of those problems which have the potential to be existential crises for Russia, Calvinists bringing bibles is the least of their worries.

The birth rate issue is a problem for most European countries. in 50 years most European countries could have a Muslim majority population. The non-violent answer to that is to simply convert Muslims, but most European countries are too secular to even think that way.

Agreed.

***Unless you’re fluent in both ancient Hebrew and Greek (were raised speaking both), don’t criticize what YOU call errors, ***

The criticism wasn’t errors in translating concepts from one language to another. The criticism relates to manuscript traditions and the passing down of different mss, which sometimes generates copyist errors.

And our comments are quite relevant. As many Orthodox note, the NKJV (the tradition off of which both the OSB and the NGB are both based) has flaws in it. Since many Orthodox consider the Septuagint as inspired (if not more so), and there are errors in that tradition as well, then some hard thinking is warranted on this subject.

Again, not relevant since the point is the Protestant attempt to evangelize a people who’ve had Christianity longer than Protestantism has been around.

Minor mss errors don’t explain away the major changes in the tenets of the faith, especially when the scripture itself is the same between mss (i.e. Jn 6:51-68; the bread and wine are only “symbols” of Jesus’ body and blood as the Protestants see it vs. the Orthodox belief that they’re literally His body and blood through the power of the Holy Spirit). Any attempt to Protestantize Russians would include this major tenet, regardless of which Bible is used.

Again, the point of all of this is the exportation of a Christianity that by it’s basic foundations is foreign, not because of mss errors but because it comes from the stripping away of Holy Tradition which, in effect, watered Christianity down to a “church on the beach” mentality. This is what would be exported to Russia via the New Geneva Bible, but it wouldn’t be the first time. Good luck to them, ‘aint gonna happen!

***Again, not relevant since the point is the Protestant attempt to evangelize a people who’ve had Christianity longer than Protestantism has been around.***

That’s only a half-truth. Any discussion of a bible translation (which includes the OSB) must take into account its manuscript tradition. Now, if there should be a moratorium on all discussions of mss tradition, fine. But that also means no discussion on the LXX either.

The problem, though, is that Mr Arakaki correctly identified the manuscript and translation issue and began to deal with it. Protestants didn’t start that discussion.

As to evangelizing Russia or not, my comments are simply dealing with the manuscript part of the blog, which appeared to be the larger point of Mr Arakaki’s post.

***”People, let’s get to the main issue: Should Calvinists export the Geneva Bible to Russia which has a Christian heritage over a thousand years old? And whose faith predates Calvin and Luther by more than five centuries?”

I get what all of you are saying Olaf, but that’s only a small part of Robert’s series, something none of you seem to be addressing at all. Why is that? The quote above is from him!

The term “Septuagint” refers to the legend that it was translated by 70 (or 72) translators. But this (questionable) legend only applies to the Pentatuch. Indeed the quality of translation of the Pentatuch is quite good. Who knows, maybe it was translated by Rabbis fluent in Hebrew and Greek. But for the rest of the bible, the quality of the Greek ranges from good to middling to just awful. The translation approach ranges from hyper literal (hardly even Greek, but Hebrew written in Greek), to hyper paraphrase. Daniel was so bad, that it only exists still in 2 manuscripts. Everyone else threw it out in favour of Theodotian’s translation.

As for the new Geneva study bible, it’s not even in Russian, so the chances it will impact Russia is roughly zero. Ironically, the chances of running across many Calvinists in Geneva are only slightly above zero.

Actually, there is a Russian language version of the Geneva Bible. Please visit the site: Bible In My Language.

Interesting. I notice that it’s not actually available though. I’ll bet that’s because they don’t sell any.

Barnabas wrote,

***but that the LXX should be, in most cases, perhaps be given priority***

If that’s the case, then what would be the point of learning Hebrew at all? It’s hard to see that move avoiding “de-Hebraicising” Jesus.

Interesting, though, Jacob, that these guys didn’t find the Orthodox Tradition “deHebraicising” Jesus:

http://abbaabeeld.blogspot.com/2011/12/av-aleksandr-in-israeli-society.html

http://byztex.blogspot.com/2013/09/the-life-of-orthodox-priest-in-jerusalem.html

http://www.antiochian.org/biography-fr-james-bernstein

Both Fr. Alexander and Fr. James were raised in Jewish homes and found in Orthodoxy an expression of faith and a spirituality much more consonant with their Jewishness than other forms of Christianity they encountered (Fr. James was Evangelical Protestant before he transitioned to Orthodoxy).

Orthodox would argue that Hebrew culture was carried right from the beginning into the Apostolic Christian Tradition in an organic way and is reflected in our liturgical and spiritual practices. It is the whole context of our approach to the Scriptures as well.

I’m glad those guys seem “pro-Jew.” My point was that if you prioritize the LXX to the degree of marginalizing the Hebrew text (and with what comes with it), it’s hard to avoid my conclusions.

Whether or not Orthodox tradition comes from the Hebrew is debatable and beside the point (though the Deponysii cogently argued the opposite point and Pope Sylvester apparently ceded it).

We know from the NT and Christian history there is both continuity and discontinuity with the Old Covenant in the Christian tradition. I just find it interesting Fr. James and Fr. Alexander, speaking from their own experience as Jewish believers, point to a distinct continuity with the Judaism they have experienced evident within the Eastern Orthodox Christian tradition, but both acknowledge the western Christian traditions, at least as they exist today, are more foreign to it.

My point was simply this: if we prioritize the LXX to the detriment of the Hebrew text, then we will lose the need to study Hebrew text (and culture!). This is especially so if we add the proposition: the LXX is inspired. If that is so, and it is so that we prioritize the LXX, then what’s the point of the Hebrew Old Testament?

It’s not by accident that phenomena such as the “Slavic Christ’ could arise.

As long as there are Hebrew-speaking people and cultures with which to share the gospel, we don’t lose our need to understand that tradition. Fr. Alexander in Jerusalem, ministering to Orthodox of Jewish descent, serves the Liturgy in Hebrew. My point was if Fr. James and Fr. Alexander are representative of Orthodox Hebrew culture, then it would appear this culture, if not the tongue per se, has in some important ways been handed down within the Eastern Orthodox Church.

Although, it’s worth noting that one of the foremost scholars of Semitic languages in the world today (e.g. he discovered a new dialect of Akkadian) is Romanian-Orthodox priest and professor Fr. Eugen Pentiuc (Holy Cross Seminary).

There is no need to completely abandon the Semitic tradition or language(s) by giving preference to the LXX, and one could easily argue that a thorough study of the OT (LXX included) requires a thorough study of Semitic language.

And for the record, while I favor the critical text tradition, I am glad the OSB relied on the NKJV instead of the NIV or even worse, the NRSV (though the NRSV did translation Matthew 1:1 correctly).

Kiki says,

***Olaf, but that’s only a small part of Robert’s series, something none of you seem to be addressing at all.***

While I didn’t do a word count, it seemed the majority of his post dealt with translation issues, not proselytizing Russians. Further, most commenters on this post, Orthodox and Protestant, also appear to think the majority of the post dealt with translation issues.

To others,

To simply my point: if the LXX is superior, then the practical result is an eclipsing of the Hebrew simply because one doesn’t resort to an inferior tradition (Hebrew) to judge a superior tradition (LXX).

I think the translation issues wouldn’t even be there if the New Geneva wasn’t developed for the PURPOSE of proselytizing the Russians who’ve been using the OSB for years already, and was that the real purpose of this particular translation? I’ve used several translations throughout my years as a Protestant and now as an Orthodox, including Greek and Hebrew. The OSB is appealing because it doesn’t skip over major tenets like what I’ve already mentioned (literal body and blood). In all the years of Bible studies as a Southern Baptist, those foundational truths were never really addressed. Deep down I knew something was missing. All I had to do, using the NIV mind you, NOT the OSB, was read those scriptures for myself. Really READ them. When I finally got my hands on the OSB I was able to get an explanation for those passages and find the Holy Tradition that had been virtually erased from my Protestant experience. Those explanations are missing from the other translations I’d been using all those years.

Now, what was the MOTIVE behind the creation of the New Geneva? We all know of flaws in one translation or another. I’m looking for the real motive behind it all and I think that’s what Robert was looking for as well, though it may have gotten lost in all the ado about translational purity (LXX v.MT). Why Russia? The Gideons have been doing “bible smuggling” for years using the KJV. Why the need by these others for a New Geneva and will it really make any difference? I think not. The Orthodox have remained Orthodox in spite of all the smuggling that went on during the Soviet era. This “new” translation is rather lacking in substance anyway, if it omits the Holy Tradition the Russian Orthodox have had for centuries. What’s the worry?

The motive behind the New Geneva is fairly simple to discern: it was the first of its kind to a particular market. It was not designed to “convert Russia.” It was designed to market to Reformed folks who got tired of Scofield and Ryrie. They might be trying that now, but I highly doubt it.

I bet a lot of Russians are poor and thick study bibles (OSB, New Geneva, whatever) are fairly pricey. That’s one of the reasons as a Protestant I never bought a New Geneva (and a friend gave me the OSB. I wanted to buy it but couldn’t afford it).

I agree Olaf, that most Russians couldn’t afford most study Bibles. I would also add that most resources are acquired from Monastery bookstores and are limited. The “Christian Bookstore” is an American practice not replicated, at least not on the same scale, in other countries so comparing translations would be seen as an activity for the seminarians or monastics.

Jacob,

One of the reasons why I liked Orthodoxy was because it favored the LXX family of texts. Yes Saint Jerome did what he did, I tend to think that his Jewish teachers influenced his decision in that regard, but regardless, I like the LXX family and it’s one of the many reasons why I became EO. We are not protestants and so why should we act like it by favoring the Masoretic? We inherited the LXX family from the Apostles. This is the tradition, and I’m pretty much happy with it!

I am about half way through “Whem God Spoke Greek” which has no discernible apologetic agenda as far as I can tell:

http://www.amazon.com/gp/aw/d/0199781729

So far a good read.

Oops. should be When God Spoke Greek

Yes, he’s an objective scholar on the issue. Definitely not by an Orthodox or biased author.

It’s published by Oxford. I can respect that. I might get it. Do you know how it compares to the works by de Silva and others? I know they aren’t exactly talking about the same thing, but it seems similar enough.

I am really not familiar with other works on the subject. As I said, I am only half way through the book (I bought it on Kindle) and I won’t get back to it for a few weeks as I have some library books to finish by their due dates. There are a few author interviews out there that I’m sure you can find through Google. I get the impression of someone who is genuinely intrigued by his subject matter and wants to share his knowledge. If you don’t like textual criticism, I guess you wouldn’t like the book, though like most good text critics writing today, he delivers his findings without the overt acid scepticism that marred., say, the 19th century founders of the craft.

Folks,

I just blocked an excessively long “comment.” Those who wish to express their views via long treatises should seriously consider starting their own blog. Comments should be short, on topic, and charitable in tone.

Robert

Is Orthodox deacon Michael Hyatt still the head honcho at Thomas Nelson Publishers, the publishers of the New Geneva Study Bible ?

Nicholas,

Good question! I checked out Michael Hyatt’s blog and learned that he was a literary agent from 1992 to 1998, the period when Thomas Nelson published the New Geneva Bible. He rejoined Thomas Nelson in 1998, served as CEO from 2005 to 2011. Please keep in mind that Thomas Nelson is a broadly Christian publisher, it is not solely an Eastern Orthodox publisher.

Robert